-

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most serious disease affecting human health worldwide. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, approximately 17.6 million people die from CVD annually[1]. By 2030, the number of people dying of CVD each year is expected to reach 23.6 million[2]. Hypertension is a major risk factor for CVD, and approximately half of all CVD events are caused by hypertension[3]. Therefore, effective hypertension prevention and treatment are essential to reduce the health risks caused by CVD.

Achieving a target blood pressure (BP) is key to treating hypertension. Patients with poor BP control suffer a significantly higher risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, heart failure, and death than those with well-controlled BP[4]. Epidemiological data from the United States showed that the BP control rate in adult hypertensive patients was 40.2% in 2013−2014[5] while the BP control rate in adult hypertensive patients in China was only 13.8% in 2012, which is much lower than that in developed countries[6].

Several factors influence BP control in patients with hypertension. Studies have shown that home BP telemonitoring (HBPT) can better help hypertensive patients control their BP than usual care (UC) and make it easier for them to achieve their target BP[7,8]. A meta-analysis based on randomized controlled clinical trials showed that HBPT can lead to a greater decrease in systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) than UC, allowing more patients to achieve the target BP[9-11]. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association Hypertension Management Guideline 2017 recommends using telemedicine interventions (HBPT alone or HBPT plus additional support) to improve BP control in patients with hypertension[12].

Almost all current clinical evidence for HBPT improvement in BP control comes from developed countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Korea. Few clinical studies have been conducted in countries with relatively low medical standards, such as China. Therefore, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine whether HBPT combined with additional support can improve BP control in Chinese patients with hypertension.

-

This was a single-center randomized controlled study conducted at the Chinese PLA General Hospital, which included former data, and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (Hospital ethics No. S2018-065-01, Clinical Research Registration No. ChiCTR2200058922). All enrolled patients were informed that they would receive one of two hypertension treatment regimens and would be followed up. All respondents provided informed consent.

-

The participants were patients with hypertension treated in our hospital during the recruitment period (August 2016 to March 2017) from 11 different provinces in China, with a 12-week follow-up period. Patients were included if they met the following criteria: 1) age ≥ 18 years; 2) previously or newly diagnosed with hypertension; 3) poor BP control (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg for patients with diabetes,) at the time of consultation; 4) in possession of a smartphone. Patients would not be included in the study if they met one or more of the following criteria: 1) SBP ≥ 180 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 110 mmHg at the time of consultation; 2) secondary hypertension; 3) patients with chronic kidney disease, with serum creatinine ≥ 2.5 mg/dL (221 μmol/L); 4) patients with chronic liver disease, with aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase four times greater than the upper limit; 5) patients undergoing hospitalization due to acute myocardial infarction, stroke, or congestive heart failure during the past 6 months; 6) patients with dementia; 7) patients who were unable to communicate due to severely impaired hearing or speech function; 8) patients with malignant tumors.

-

Our preliminary study showed that HBPT could help approximately 65% of patients with hypertension achieve their target BP, with a conservative estimate of 60% (see our pre test results). In previous outpatients with hypertension at our hospital, the rate of meeting the target BP was approximately 37%, with a conservative estimate of 35%[13]. In this study α = 0.05, β = 0.10, the sample size was estimated using PASS software (version 15.0.5, NCSS NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah) and 79 patients were needed in each group. Considering a 10% loss to follow-up, 95 patients were enrolled in each group.

-

Potentially eligible patients were invited to our research clinics, where they were screened for eligibility. Informed consent was obtained, baseline measurements were taken, and questionnaires were administered. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to the HBPT-plus or the UC group (1:1) according to their odd or even clinical ID numbers. Neither the participants nor investigators were blinded to the group assignments in this open trial. Statistical analysis was performed by a statistician upon completion of the trial.

-

Home BP remote monitoring with additional support is a closed-loop feedback system using a software application, cloud platform, blood pressure monitoring apparatus, and a management team. Interventions received by the HBPT-plus group (95 patients) included: 1) remote HBPT (the patients were offered an automated sphygmomanometer, which uploaded BP readings onto the BP monitoring application (APP), which can be seen by both patients and staff), 2) patient education (health education knowledge was regularly sent via the BP monitoring APP), and 3) remote hypertension treatment management guided by a clinician or pharmacist (by phone or BP monitoring APP). Based on the BP measurement data uploaded by the patient, the system calculates the average BP and sends it to the patient and staff via a BP-monitoring APP every week. In the first two weeks of the study, the patients were asked to measure their BP every morning and evening. Two weeks later, if the patient’s BP remained stable, it was decreased to measuring the BP 1–2 times every 1–2 days[14]. If the patient failed to take BP measurements for five consecutive days, the staff would remind and supervise him by phone. If the patients’ BP failed to reach the standard for two consecutive weeks (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg, for patients with diabetes), the nurse would follow up the patient’s medication within these two weeks by phone, and a pharmacist or clinician would adjust the dose, usage, or type according to the patients’ BP level in accordance with the latest medication guidelines, and deliver individualized lifestyle guidance. Patients in the HBPT-plus group were regularly followed up for drug adherence (every two weeks).

Patients in the UC group (n = 95) were treated according to the treatment regimens provided by the first-visit physician based on the latest guidelines. The patients were recommended to undergo home BP monitoring with a normal family sphygmomanometer and return for outpatient visits every 4 weeks (no mandatory requirements). If patients visit a physician, their treatment regimens would be adjusted based on the results of home and outpatient BP monitoring. Consistent with the HBPT-plus group, patients were regularly followed up for drug compliance (every two weeks).

All patients underwent ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) within 3 days of enrolment and within 3 days of the end of the trial (12 weeks). BP was automatically measured every 30 min during the day (06:00–20:00) and every 1 h at night (20:00–06:00)[15]. If the number of effective BP readings within 24 h was > 85%, then the number of monitoring readings was considered valid.

-

The primary endpoints of the study were changes in mean SBP and DBP between the baseline and 12-week follow-up as well as the proportion of patients achieving the target BP and dipper BP pattern at the 12-week follow-up. The 24-hour, daytime, and nighttime mean SBP and DBP were defined as the mean of the all-day, daytime (06:00–20:00), and nighttime (20:00–06:00) BP measurements according to ABPM readings. Achieving target BP was defined as a 24-hour mean BP < 130/80 mmHg, daytime mean BP < 135/85 mmHg, and nighttime mean BP < 120/70 mmHg. The dipper blood pressure pattern was defined as a nocturnal BP fall of > 10% of daytime values or a night/day BP ratio of 0.8–0.9. A diminished nocturnal decrease in BP is associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes[15].

-

The secondary endpoints were blood pressure variability (BPV) and drug adherence. In our study, BPV was defined as the degree of fluctuation in BP during 24-hour ABPM, as measured by the standard deviation of the mean BP. The formula for calculating drug adherence was as follows: (number of days taking the medication as required / total days required to take the medication) × 100%.

-

All statistical analyses were conducted based on a per-protocol analysis, and the mean, standard deviation, and percentage were used to describe the baseline clinical characteristics of the patients. Intergroup comparisons of continuous variables were performed using the t-test. Intergroup comparisons of categorical variables were performed using Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 23.0; Authorization No.6b4543b2xxxxf3c69a68). A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

-

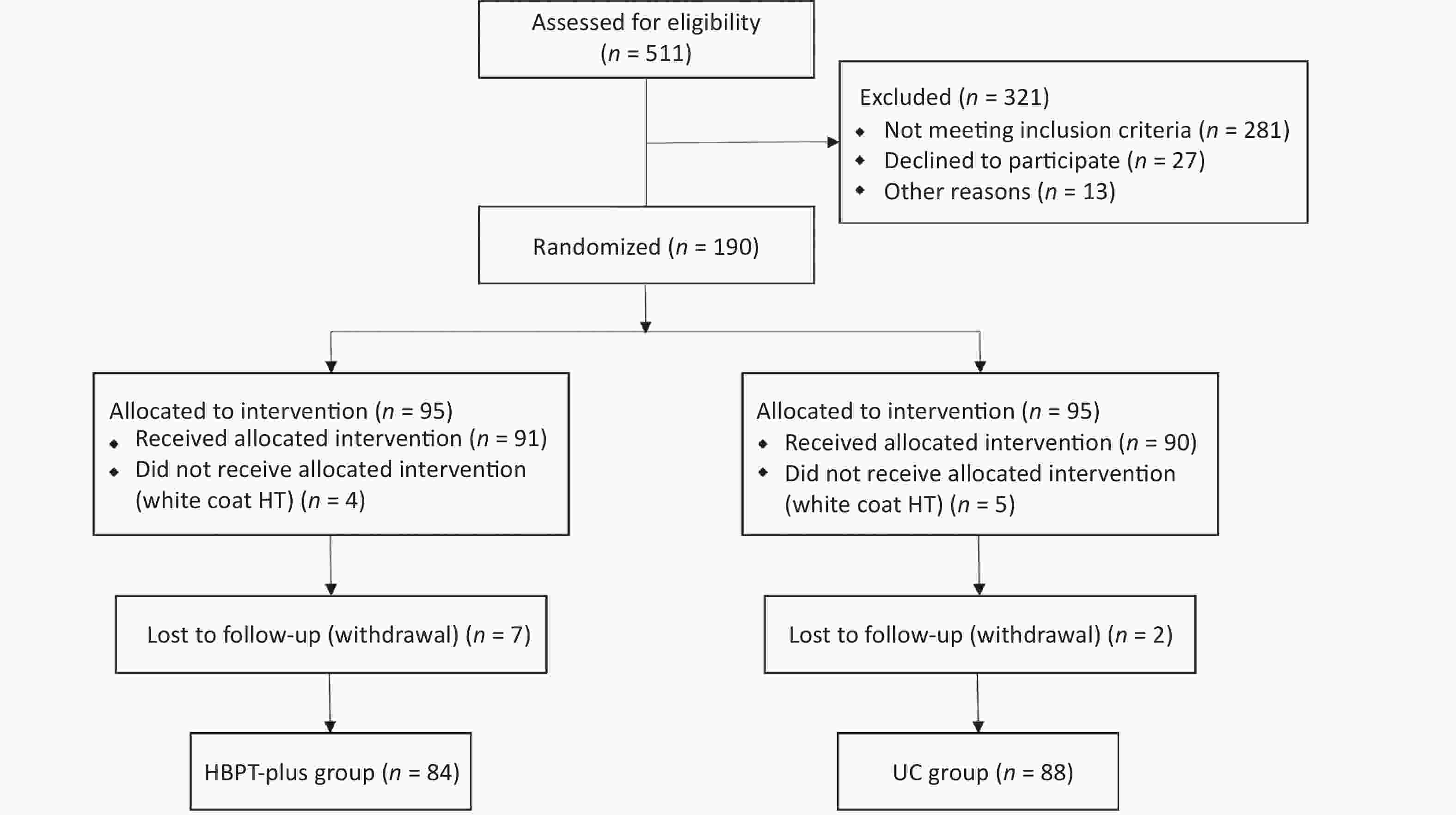

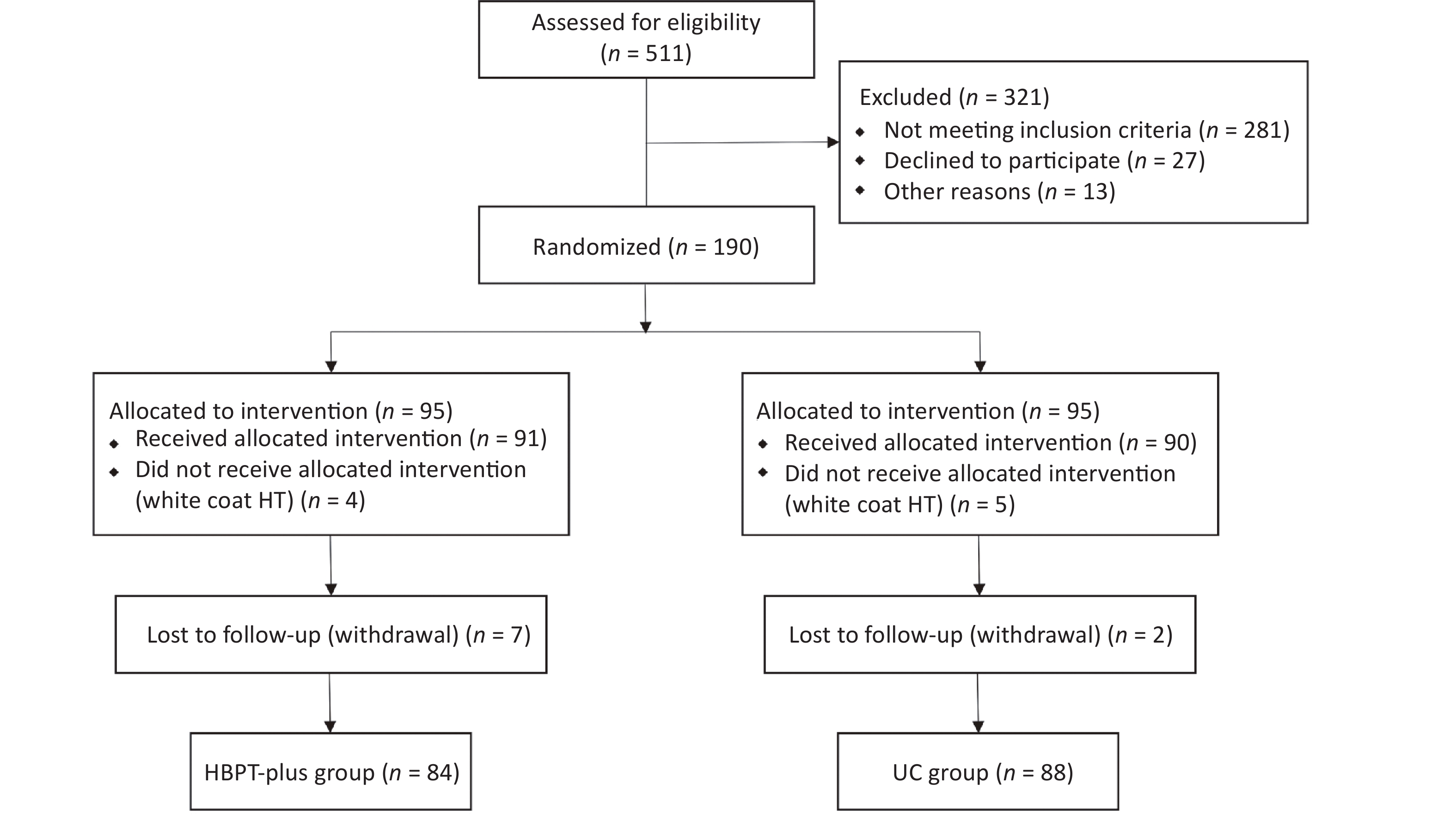

A total of 511 patients with hypertension were screened. After excluding 321 patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria, 190 hypertensive patients were randomized into the HBPT-plus and UC groups. By the end of the 3-month follow-up, seven patients in the HBPT-plus group and two patients in the UC group had withdrawn from the study. During the study, 9 patients with white coat hypertension were also identified. Therefore, 172 patients were included in the final analysis (84 in the HBPT-plus group and 88 in the UC group) (Figure 1).

According to the latest guidelines, treatment plans vary for different individual conditions with different numbers, classes, and dosages of antihypertensive medication. The antihypertensive drugs administered to patients were diuretics, calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor blockers. The mean number of antihypertensive medication classes was 1.7 ± 0.6 in the HBPT-plus group and 1.6 ± 0.5 in the UC group at baseline.

There were no significant differences in age, sex, body mass index, family history of hypertension, waist-to-hip ratio, hypertension grade, mean number of antihypertensive medication classes, history of coronary heart disease, history of diabetes mellitus, or proportion of newly or previously diagnosed hypertension between the two groups (Table 1). There was no difference in the baseline office BP (Table 1), baseline 24-hour mean BP, daytime mean BP, or nighttime mean BP (Table 2) between the two groups. The 24-hour mean SBP and DBP were approximately 10 mmHg and 4 mmHg lower than the office SBP and DBP, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

Characteristics HBPT-plus group (n = 84) UC group (n = 88) P-value Age (years) 50.96 ± 10.50 51.45 ± 12.22 0.778 Males, n (%) 50 (59.5%) 51 (58.0%) 0.834 BMI (kg/m2) 27.33 ± 3.11 26.85 ± 3.71 0.365 WHR 0.93 ± 0.68 0.92 ± 0.52 0.302 Blood pressure (mmHg) Systolic blood pressure 151.92 ± 10.74 151.18 ± 9.30 0.632 Diastolic blood pressure 91.01 ± 9.98 90.60 ± 12.90 0.817 History of HTN, n (%) 36 (42.9) 26 (30.0) 0.052 HTN Grade, n (%) Class I 57 (67.9) 64 (72.7) 0.485 Class II 27 (32.1) 24 (27.3) HTN Categories, n (%) New diagnosed 30 (35.7) 22 (25.0) 0.152 Previous diagnosed 54 (64.3) 64 (72.7) DM 21 (25.0) 18 (20.5) 0.450 CAD 33 (39.3) 37 (42.0) 0.713 No. of hypertension medication classes 1.7 ± 0.6 1.6 ± 0.5 0.236 Note. BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; HTN, hypertension; UC, usual care; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio. Data are presented as mean ± SD or number and percentage. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Table 2. Comparison of mean SBP and DBP changes between HBPT-plus group and UC group

Variables HBPT plus group (n = 84) UC group (n = 88) P-value 24 h mean systolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 139.76 ± 9.48 139.97 ± 9.45 0.888 Week 12 127.52 ± 7.12 132.81 ± 5.74 < 0.001 Change 12.01 ± 4.82 7.16 ± 8.57 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 24 h mean diastolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 86.95 ± 9.12 86.48 ± 8.03 0.475 Week 12 78.65 ± 6.13 82.38 ± 6.66 < 0.001 Change 8.11 ± 9.84 4.10 ± 8.41 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Daytime mean systolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 142.90 ± 9.88 143.51 ± 9.83 0.687 Week 12 130.73 ± 7.01 136.27 ± 6.09 < 0.001 Change 11.92 ± 6.19 7.24 ± 9.05 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Daytime mean diastolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 89.64 ± 9.73 89.22 ± 8.12 0.755 Week 12 81.12 ± 7.01 85.02 ± 6.83 < 0.001 Change 8.24 ± 10.81 4.19 ± 9.11 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Nighttime mean systolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 133.42 ± 11.74 132.88 ± 11.20 0.542 Week 12 121.05 ± 8.67 125.76 ± 6.63 < 0.001 Change 12.20 ± 7.96 7.11 ± 10.49 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Nighttime mean diastolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 81.67 ± 9.53 80.89 ± 9.48 0.780 Week 12 73.75 ± 6.85 77.06 ± 7.91 < 0.001 Change 7.92 ± 10.27 3.83 ± 8.93 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.004 Note. ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; UC, usual care. Data are presented as mean ± SD or number and percentage. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The mean number of antihypertensive medication classes increased from 1.7 ± 0.6 at baseline to 2.2 ± 0.7 at 12 weeks in the HBPT-plus group and from 1.6 ± 0.5 at baseline to 1.9 ± 0.6 at 12 weeks in the UC group.

-

At the 12th week of follow-up, BP levels (including 24-hour mean BP, daytime mean BP, and nighttime mean BP) in both the HBPT-plus and UC groups were significantly lower than the baseline levels (P < 0.01). The reduction of the BP (including 24-hour mean BP, daytime mean BP, and nighttime mean BP) in the HBPT-plus group was greater than that in the UC group (P < 0.01) (difference in changes between groups: 24-hour mean SBP and DBP were 4.85 mmHg and 4.01 mmHg, respectively) (Table 2).

At the beginning of the study, there was no significant difference in participants achieving the target BP (including 24-hour BP, daytime BP, and nighttime BP) between the HBPT-plus group and the UC group. The proportion of participants who achieved their target BP at the end of the study in both the HBPT-plus and UC groups was significantly higher than at the start, and the proportion in the HBPT-plus group was significantly higher than that in the UC group (P < 0.01). The proportion of patients in the HBPT-plus group who achieved the target BP at 24 hours was 71.4%, while it was only 25.0% in the UC group [odds ratio = 2.625, 95% confidence interval = 1.833–3.759]. (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of the proportion of patients achieving the target BP and dipper BP pattern between HBPT plus group and UC group

Variables HBPT-plus group (n = 84), n (%) UC group (n = 88), n (%) OR 95% CI P-value 24 h mean BP (130/80 mmHg) Baseline 5 (6.0) 6 (6.8) 0.991 0.916−1.071 0.817 12 weeks 60 (71.4) 22 (25.0) 2.625 1.833−3.759 < 0.001 Daytime mean BP (135/85 mmHg) Baseline 9 (10.7) 11 (12.5) 0.980 0.879−1.092 0.715 12 weeks 69 (82.1) 31 (35.2) 3.627 2.236−5.885 < 0.001 Nighttime mean BP (120/70 mmHg) Baseline 5 (6.0) 3 (3.4) 0.961 1.098 0.489 12 weeks 50 (59.5) 18 (20.5) 1.965 1.485−2.601 < 0.001 Dipper blood pressure pattern Baseline 35 (41.7) 38 (43.2) 0.974 0.754−1.259 0.841 12 weeks 56 (66.7) 42 (47.7) 1.568 1.091−2.253 0.012 Note. BP, blood pressure; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; UC, usual care. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. -

At the beginning of the study, 35 patients (41.7%) in the HBPT-plus group and 38 patients (45.2%) in the UC group had a dipper blood pressure pattern. At the end of the study, the number of patients with a dipper blood pressure pattern had increased to 56 (66.7%) in the HBPT-plus group and 42 (47.7%) which was not a significant change in the UC group. The proportion of patients with dipper blood pressure patterns in the HBPT-plus group was significantly higher than that in the UC group (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

At the beginning of the study, there was no significant difference in BPV between the HBPT-plus and UC groups. At the end of the study, the BPV of the two groups was significantly lower than at the beginning and the BPV in the HBPT-plus group was significantly lower than that in the UC group (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of BPV and drug adherence between HBPT-plus group and UC group

Variables HBPT-plus group (n = 84) UC group (n = 88) P-value BPV of 24 h mean Systolic BP Baseline 18.91 ± 4.46 19.47 ± 5.56 0.463 Week 12 13.33 ± 2.90 15.82 ± 3.82 < 0.001 Change 5.46 ± 4.73 3.65 ± 6.66 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 BPV of 24 h mean Diastolic BP Baseline 15.73 ± 4.96 16.18 ± 5.16 0.558 Week 12 11.01 ± 3.27 13.81 ± 3.52 < 0.001 Change 4.87 ± 5.76 2.37 ± 6.31 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 BPV of Daytime mean Systolic BP Baseline 18.06 ± 4.90 17.39 ± 3.78 0.280 Week 12 12.39 ± 3.36 15.51 ± 4.60 < 0.001 Change 5.67 ± 5.97 1.83 ± 5.69 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.004 BPV of Daytime mean Diastolic BP Baseline 15.75 ± 6.48 15.41 ± 5.19 0.375 Week 12 10.35 ± 3.50 13.30 ± 3.70 < 0.001 Change 5.15 ± 6.93 2.11 ± 6.67 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.002 BPV of Nighttime mean Systolic BP Baseline 15.46 ± 4.30 16.33 ± 5.19 0.234 Week 12 12.14 ± 3.29 14.13 ± 3.64 < 0.001 Change 3.37 ± 4.71 2.26 ± 5.66 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.001 BPV of Nighttime mean Diastolic BP Baseline 12.61 ± 3.13 13.22 ± 3.39 0.223 Week 12 9.78 ± 3.31 12.28 ± 3.48 < 0.001 Change 3.25 ± 4.41 0.93 ± 4.76 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.073 Drug adherence 93.6 ± 7.9 78.1 ± 12.2 < 0.001 Note. BPV, blood pressure variability; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; UC, usual care. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. At the 12th week of follow-up, drug adherence in the HBPT-plus group was significantly higher than that in the UC group (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

-

The results of this randomized controlled trial showed that compared with UC, HBPT plus additional support (patient education and remote pharmacist or physician BP management) could lead to a more significant BP reduction and enable more patients with hypertension to achieve the target BP, maintain a dipper blood pressure pattern, and have lower BPV. We also found that patients in the HBPT-plus group had significantly higher drug adherence.

Patients in the HBPT-plus group had a greater BP reduction than those in the UC group, possibly because of higher drug adherence in the HBPT-plus group. The timely adjustment of medications by clinicians and pharmacists may be another reason. A previous meta-analysis has shown that HBPT achieved an additional BP reduction (24 h ABPM) of 2.71/1.08 mmHg compared with UC[16]. In our study, the HBPT-plus group achieved an even greater BP reduction, which was possibly attributable to the additional support. Previous studies have also shown that HBPT plus additional support can result in greater BP reduction than HBPT alone (3.44/1.40 mmHg) [16], indicating that additional support may help better control BP. A meta-analysis showed that self-monitoring alone was not associated with lower BP or better control, but in conjunction with co-interventions (including systematic medication titration by doctors, pharmacists, or patients, education, or lifestyle counseling) led to clinically significant BP reduction[17]. A recent study found that HBPT plus led to blood pressure dropping from 151.7/86.4 to 138.4/80.2 mmHg in the intervention group, and the results at 12 months showed greater divergence than at 6 months, which suggested that the intervention might have an ongoing impact[18].

The proportion of patients achieving the target BP in the HBPT-plus group in our study was higher than that of the intervention group in other studies, whereas the proportion of patients achieving the target BP in the UC group was significantly lower than that in the UC group in another study[19-20]. The high proportion of the HBPT-plus group achieving the target BP was attributed to measuring and uploading BP data more frequently in our study. In addition, pharmacists and physicians had higher management intentions for patients who did not meet the standards. If the patient’s BP did not reach the standard in two weeks, we followed up by phone and adjusted the treatment regimen. The study lasted for 12 weeks. In such a short period, the proportion of patients achieving the target BP is likely to be high, but it may decrease to some extent with time. The low proportion of patients in the UC group who achieved their target BPs may be attributed to low drug adherence and low awareness of hypertension. According to 2012 data, the overall awareness rate in Chinese patients with hypertension was only 46.5%[6].

We also studied the effects of HBPT-plus on BP rhythm and BPV. The proportion of dipper blood pressure patterns in the HBPT group was significantly higher than that in the UC group at the end of the study, while BPV was significantly lower in the UC group. Thus, this study suggests that HBPT plus may reduce adverse events in patients with hypertension by helping them restore a normal BP rhythm and reduce BPV. However, confirmation of this conclusion requires further follow-up.

Drug adherence determines the therapeutic effects in the treatment of chronic diseases. Previous studies have found that drug adherence in the HBPT group was 92%, compared with 74% in the control group[21]. Kim et al. also found in their randomized controlled trial that HBPT combined with remote physician care improved patients’ drug adherence compared to HBPT alone[19]. Our findings were consistent with these results.

The more significant BP reduction in the intervention group may be attributed to the following points: first, the improvement of patient compliance: changing patients’ inaccurate health concepts and treatment inertia, strengthening their subjective initiative to actively cooperate with medical staff; second, a reasonable and accurate drug plan: based on layer evaluation and BP monitoring at home, choosing the best drug plan to lower BP while controlling hypertension in the morning; and third, improvement of the patient’s lifestyle: stabilizing the effect of lowering BP and helping BP reach the standard smoothly for the long-term.

Our study had several limitations. First, it was a single-center study conducted in a large hospital in a developed city in China; therefore, the results may not be applicable to hospitals with lower levels of healthcare. According to the inclusion criteria of this study, patients needed to have a smartphone and be proficient in using it, which is unlikely for hypertensive patients in remote and impoverished areas of China. Second, the follow-up period was 3 months, which is relatively short. Therefore, it is impossible to determine the benefits of HBPT plus hypertension management for long-term BP management. Third, only patients with Grade I or II hypertension were included. Patients with chronic kidney disease were excluded, and no patients aged > 75 years were eventually enrolled. Thus, it is difficult to ascertain whether the findings of this study can be applied to patients with grade III hypertension and chronic kidney disease, whose BP is more difficult to control than those with normal hypertension and elderly hypertensive patients.

In China, there are a large number of hypertension patients with low BP control rates and limited medical resources. With the rapid development of mobile medical care and remote monitoring technology, HBPT-plus could overcome the limitations of traditional BP management and provide new insights into hypertension control, which would be a strategy worth further exploration. In follow-up research and the application of HBPT plus in China, full consideration should be given to equipment certification, staff qualifications, payment methods, etc. Furthermore, it is necessary to establish large data-based assessment systems, early warning models, and auxiliary decision-making systems for hypertension. It is also important to perfect service structures, legal systems, insurance strategies, and business models, to focus on cardiovascular disease[22-24].

-

Home blood pressure telemonitoring with additional support was effective in improving BP control compared to UC over 3 months. Therefore, promoting this improved BP management method among most patients with hypertension and evaluating its long-term benefits and cost-effectiveness will be the direction of our future efforts.

doi: 10.3967/bes2023.063

Effect of Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring Plus Additional Support on Blood Pressure Control: A Randomized Clinical Trial

-

Abstract:

Objective Current clinical evidence on the effects of home blood pressure telemonitoring (HBPT) on improving blood pressure control comes entirely from developed countries. Thus, we performed this randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether HBPT plus support (patient education and clinician remote hypertension management) improves blood pressure control more than usual care (UC) in the Chinese population. Methods This single-center, randomized controlled study was conducted in Beijing, China. Patients aged 30–75 years were eligible for enrolment if they had blood pressure [systolic (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg; or SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 80 mmHg with diabetes]. We recruited 190 patients randomized to either the HBPT or the UC groups for 12 weeks. The primary endpoints were blood pressure reduction and the proportion of patients achieving the target blood pressure. Results Totally, 172 patients completed the study, the HBPT plus support group (n = 84), and the UC group (n = 88). Patients in the plus support group showed a greater reduction in mean ambulatory blood pressure than those in the UC group. The plus support group had a significantly higher proportion of patients who achieved the target blood pressure and maintained a dipper blood pressure pattern at the 12th week of follow-up. Additionally, the patients in the plus support group showed lower blood pressure variability and higher drug adherence than those in the UC group. Conclusion HBPT plus additional support results in greater blood pressure reduction, better blood pressure control, a higher proportion of dipper blood pressure patterns, lower blood pressure variability, and higher drug adherence than UC. The development of telemedicine may be the cornerstone of hypertension management in primary care. -

Key words:

- Hypertension /

- Telemonitoring /

- Blood pressure control /

- Additional support

注释: -

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

Characteristics HBPT-plus group (n = 84) UC group (n = 88) P-value Age (years) 50.96 ± 10.50 51.45 ± 12.22 0.778 Males, n (%) 50 (59.5%) 51 (58.0%) 0.834 BMI (kg/m2) 27.33 ± 3.11 26.85 ± 3.71 0.365 WHR 0.93 ± 0.68 0.92 ± 0.52 0.302 Blood pressure (mmHg) Systolic blood pressure 151.92 ± 10.74 151.18 ± 9.30 0.632 Diastolic blood pressure 91.01 ± 9.98 90.60 ± 12.90 0.817 History of HTN, n (%) 36 (42.9) 26 (30.0) 0.052 HTN Grade, n (%) Class I 57 (67.9) 64 (72.7) 0.485 Class II 27 (32.1) 24 (27.3) HTN Categories, n (%) New diagnosed 30 (35.7) 22 (25.0) 0.152 Previous diagnosed 54 (64.3) 64 (72.7) DM 21 (25.0) 18 (20.5) 0.450 CAD 33 (39.3) 37 (42.0) 0.713 No. of hypertension medication classes 1.7 ± 0.6 1.6 ± 0.5 0.236 Note. BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; HTN, hypertension; UC, usual care; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio. Data are presented as mean ± SD or number and percentage. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Table 2. Comparison of mean SBP and DBP changes between HBPT-plus group and UC group

Variables HBPT plus group (n = 84) UC group (n = 88) P-value 24 h mean systolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 139.76 ± 9.48 139.97 ± 9.45 0.888 Week 12 127.52 ± 7.12 132.81 ± 5.74 < 0.001 Change 12.01 ± 4.82 7.16 ± 8.57 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 24 h mean diastolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 86.95 ± 9.12 86.48 ± 8.03 0.475 Week 12 78.65 ± 6.13 82.38 ± 6.66 < 0.001 Change 8.11 ± 9.84 4.10 ± 8.41 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Daytime mean systolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 142.90 ± 9.88 143.51 ± 9.83 0.687 Week 12 130.73 ± 7.01 136.27 ± 6.09 < 0.001 Change 11.92 ± 6.19 7.24 ± 9.05 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Daytime mean diastolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 89.64 ± 9.73 89.22 ± 8.12 0.755 Week 12 81.12 ± 7.01 85.02 ± 6.83 < 0.001 Change 8.24 ± 10.81 4.19 ± 9.11 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Nighttime mean systolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 133.42 ± 11.74 132.88 ± 11.20 0.542 Week 12 121.05 ± 8.67 125.76 ± 6.63 < 0.001 Change 12.20 ± 7.96 7.11 ± 10.49 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 Nighttime mean diastolic BP (mmHg) Baseline 81.67 ± 9.53 80.89 ± 9.48 0.780 Week 12 73.75 ± 6.85 77.06 ± 7.91 < 0.001 Change 7.92 ± 10.27 3.83 ± 8.93 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.004 Note. ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; UC, usual care. Data are presented as mean ± SD or number and percentage. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Table 3. Comparison of the proportion of patients achieving the target BP and dipper BP pattern between HBPT plus group and UC group

Variables HBPT-plus group (n = 84), n (%) UC group (n = 88), n (%) OR 95% CI P-value 24 h mean BP (130/80 mmHg) Baseline 5 (6.0) 6 (6.8) 0.991 0.916−1.071 0.817 12 weeks 60 (71.4) 22 (25.0) 2.625 1.833−3.759 < 0.001 Daytime mean BP (135/85 mmHg) Baseline 9 (10.7) 11 (12.5) 0.980 0.879−1.092 0.715 12 weeks 69 (82.1) 31 (35.2) 3.627 2.236−5.885 < 0.001 Nighttime mean BP (120/70 mmHg) Baseline 5 (6.0) 3 (3.4) 0.961 1.098 0.489 12 weeks 50 (59.5) 18 (20.5) 1.965 1.485−2.601 < 0.001 Dipper blood pressure pattern Baseline 35 (41.7) 38 (43.2) 0.974 0.754−1.259 0.841 12 weeks 56 (66.7) 42 (47.7) 1.568 1.091−2.253 0.012 Note. BP, blood pressure; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; UC, usual care. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Table 4. Comparison of BPV and drug adherence between HBPT-plus group and UC group

Variables HBPT-plus group (n = 84) UC group (n = 88) P-value BPV of 24 h mean Systolic BP Baseline 18.91 ± 4.46 19.47 ± 5.56 0.463 Week 12 13.33 ± 2.90 15.82 ± 3.82 < 0.001 Change 5.46 ± 4.73 3.65 ± 6.66 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 BPV of 24 h mean Diastolic BP Baseline 15.73 ± 4.96 16.18 ± 5.16 0.558 Week 12 11.01 ± 3.27 13.81 ± 3.52 < 0.001 Change 4.87 ± 5.76 2.37 ± 6.31 P-value (within group) < 0.001 < 0.001 BPV of Daytime mean Systolic BP Baseline 18.06 ± 4.90 17.39 ± 3.78 0.280 Week 12 12.39 ± 3.36 15.51 ± 4.60 < 0.001 Change 5.67 ± 5.97 1.83 ± 5.69 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.004 BPV of Daytime mean Diastolic BP Baseline 15.75 ± 6.48 15.41 ± 5.19 0.375 Week 12 10.35 ± 3.50 13.30 ± 3.70 < 0.001 Change 5.15 ± 6.93 2.11 ± 6.67 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.002 BPV of Nighttime mean Systolic BP Baseline 15.46 ± 4.30 16.33 ± 5.19 0.234 Week 12 12.14 ± 3.29 14.13 ± 3.64 < 0.001 Change 3.37 ± 4.71 2.26 ± 5.66 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.001 BPV of Nighttime mean Diastolic BP Baseline 12.61 ± 3.13 13.22 ± 3.39 0.223 Week 12 9.78 ± 3.31 12.28 ± 3.48 < 0.001 Change 3.25 ± 4.41 0.93 ± 4.76 P-value (within group) < 0.001 0.073 Drug adherence 93.6 ± 7.9 78.1 ± 12.2 < 0.001 Note. BPV, blood pressure variability; HBPT, home blood pressure telemonitoring; UC, usual care. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. -

[1] GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet, 2017; 390, 1151−210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9 [2] Laslett LJ, Alagona Jr P, Clark III BA et al. Worldwide environment of cardiovascular disease: Prevalence, diagnosis, therapy, and policy issues: A report from the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2012; 60, S1−49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.002 [3] Lackland DT, Weber MA. Global burden of cardiovascular disease and stroke: hypertension at the core. Can J Cardiol, 2015; 31, 569−71. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.009 [4] Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2020; 141, e139−596. [5] Zhang YY, Moran AE. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among young adults in the United States from 1999 to 2014. Hypertension, 2017; 70, 736−42. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09801 [6] Ma LY, Chen WW et al. China Cardiovascular Diseases Report 2018: an updated summary. J Geriatr Cardiol, 2020; 17, 1−8. [7] Omboni S, Panzeri E, Campolo L. E-health in hypertension management: An insight into the current and future role of blood pressure telemonitoring. Curr Hypertens Rep, 2020; 22, 42. doi: 10.1007/s11906-020-01056-y [8] Pellegrini D, Torlasco C, et al. Contributions of telemedicine and information technology to hypertension control. Hypertens Res, 2020; 43, 621−8. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0422-4 [9] Omboni S, Gazzola T, et al. Clinical usefulness and cost-effectiveness of home blood pressure telemonitoring: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Hypertens, 2013; 31, 455−67. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835ca8dd [10] Verberk WJ, Kessels AG, Thien T. Telecare is a valuable tool for hypertension management. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Press Monit, 2011; 16, 149−55. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e328346e092 [11] Liu S, Dunford SD, Leung YW et al. Reducing blood pressure with internet-based interventions: A meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol, 2013; 29, 613−21. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.02.007 [12] Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018; 71, e127−248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006 [13] Lin FL, Zhan YQ, Jia GX, et al. Blood pressure control rate and its influencing factors in Chinese hypertensive outpatients. Chin J Hypertens, 2013; 21, 170−4. [14] Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, et al. European society of hypertension practice guidelines for home blood pressure monitoring. J Hum Hypertens, 2010; 24, 779−85. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.54 [15] O'Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, et al. European society of hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens, 2013; 31, 1731−68. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328363e964 [16] Duan Y, Xie Z, Dong F, et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure telemonitoring: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J Hum Hypertens, 2017; 31, 427−37. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2016.99 [17] Tucker KL, Sheppard JP, Stevens R, et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med, 2017; 14, e1002389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002389 [18] McManus RJ, Little P, Stuart B, et al. Home and online management and evaluation of blood pressure (HOME BP) using a digital intervention in poorly controlled hypertension: randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 2021; 372, m4858. [19] Kim YN, Shin DG, Park S, et al. Randomized clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of remote patient monitoring and physician care in reducing office blood pressure. Hypertens Res, 2015; 38, 491−7. doi: 10.1038/hr.2015.32 [20] Thiboutot J, Sciamanna CN, Falkner B, et al. Effects of a web-based patient activation intervention to overcome clinical inertia on blood pressure control: cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res, 2013; 15, e158. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2298 [21] Marquez-Contreras E, Martell-Claros N, Gil-Guillen V, et al. Efficacy of a home blood pressure monitoring programme on therapeutic compliance in hypertension: the EAPACUM-HTA study. J Hypertens, 2006; 24, 169−75. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000198023.53859.a2 [22] The Writing Committee of the Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China. Report on cardiovascular health and diseases in China 2021: an updated summary. writing committee of the report on cardiovascular health and diseases in China. Biomed Environ Sci, 2022; 35, 573−603. [23] Wang ZQ, Zhai Y, Li M, et al. Association between baseline SBP/DBP and all-cause mortality in residents of Shanxi, China: a population-based cohort study from 2002 to 2015. Biomed Environ Sci, 2021; 34, 1−8. [24] Sai XY, Gao F, Zhang WY, et al. Combined effect of smoking and obesity on coronary heart disease mortality in Male veterans: a 30-year cohort study. Biomed Environ Sci, 2021; 34, 184−91. -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links