-

Tetanus is the only non-communicable disease among vaccine-preventable infectious diseases. It is caused by an infection with Clostridium tetanus bacterium and is characterized by continuous tonic contraction and paroxysmal spasms of skeletal muscles throughout the body[1]. Tetanus has a relatively high incidence in developing countries, economically impoverished areas, and areas prone to natural disasters[2]. Tetanus is a serious and potentially fatal disease with diverse pathogenic factors. Without any treatment, the case fatality is nearly 100%. Despite aggressive treatment, tetanus still results in 10,000 to 300,000 deaths annually, with the case fatality ranging from 5% to 48%[3,4]. Moreover, the pathogenic tetanus bacteria are widely present in the natural environment and the gastrointestinal tract of animals[1,5]. This widespread presence makes it difficult to avoid exposure, rendering the eradication of tetanus futile.

According to the data jointly released by World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), among the reported tetanus cases globally in 2016, 85% were non-neonatal tetanus[6]. China lacks a comprehensive epidemiological surveillance and reporting system for non-neonatal tetanus. Data on the epidemiological characteristics and disease burden of non-neonatal tetanus are insufficient. In China, most non-neonatal tetanus cases occur in townships and rural areas, and the reported prevalence may be underestimated due to inadequate awareness and monitoring of non-neonatal tetanus in primary healthcare facilities[7]. There is still a wide gap in the reported case fatality rates of tetanus between China and developed countries, indicating that China still faces challenges in managing non-neonatal tetanus[5,8].

This study aimed to analyze the clinical characteristics and hospitalization costs of non-neonatal tetanus by collecting data from patients diagnosed with the disease over an 11-year period in Guangxi, an economically underdeveloped province in southwest China. Additionally, the study sought to explore potential risk factors associated with disease severity and fatality, with the objective of providing a scientific basis for the prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment of non-neonatal tetanus.

This retrospective study was conducted on 236 confirmed non-neonatal tetanus patients admitted to three hospitals in Guangxi, China, including Guangxi International Zhuang Medical Hospital, Fourth People’s Hospital of Nanning, and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University from July 2011 to July 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients were older than 28 days, met the diagnostic criteria for tetanus, and case data were complete. At least one of the following diagnostic criteria applied: (1) Lockjaw or grimace; (2) painful muscle spasms.

Medical records of 236 patients were collected from the hospital’s case system. The information obtained included: sex, age, date of birth, occupation, residence, time of admission, vaccination history, pathogenic factors, etiological types, injury sites, etiological management, whether to prevent tetanus, incubation period, first symptoms, time from onset to the initial visit, whether to first visit and hospital level of initial visit, co-morbidities and complications, forms of tetanus, grading of disease severity, passive immunization drug use, tracheal intubation or tracheotomy, admission of intensive care unit (ICU), length of a hospital stay, outcome, cause of death, type of insurance, hospitalization expenses, etc. The outcome variables for this study included categorizing non-neonatal tetanus cases into groups I, II, III, and IV based on the Ablett scale[7] (Supplementary Table S1, available in www.besjournal.com), as well as the death or survival outcome.

Grade Trismus Spasms Dysphagia Respiratory embarrassment Autonomic nervous dysfunction I Mild to moderate No Little or no No No II Moderate Mild to moderate but short Mild Respiratory rate 30–40 No III Severe Severe, persistent Severe Respiratory rate > 40, apnoeic spells Tachycardia > 120 IV Severe Severe, persistent Severe Respiratory rate > 40, apnoeic spells Severe hypertension, tachycardia, hypotension, bradycardia Table S1. Grading of the severity of tetanus according to the Ablett scale

The sociodemographic and clinical variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Quantitative data were expressed as median and interquartile range [M (IQR)], and comparison between groups was performed by the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Qualitative data were expressed as percentage or component ratio (%), and comparison between groups was performed by chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact probability test. The trend test was performed using Spearman analysis. Univariate analysis, binary or ordered logistic multivariate regression models were used for influencing factor analysis. Odds ratio (OR) and confidence interval (95% Cl) were used to assess the risk and prognostic factors of non-neonatal tetanus. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used for all tests to determine statistical significance. SPSS statistical software version 26.0 was used for statistics and analysis.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients are described in Table 1. From July 2011 to July 2021, 236 cases of non-neonatal tetanus were included, with a gender ratio (male/female) of 1.07. The median age of patients was 60.50 years (IQR, 21.00 years), and the median age of males (56.00 years) was lower than that of females (67.00 years). The majority of the patients were elderly. In China, Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis (DTP) vaccine has been a part of the national immunization program since 1978. Therefore, people born before 1978 and have not received vaccinations have lower immunity and may have multiple underlying diseases, making them more vulnerable to tetanus[9]. In terms of occupational distribution, farmers comprised the majority of the patients (67.80%), followed by workers (11.02%), retirees (8.90%), and laid-off/unemployed persons (5.93%). Among the 236 patients, the majority (91.53%) had no history of tetanus toxoid-containing vaccine (TTCV) vaccination, and the rest (8.47%) had completed full TTCV vaccination. The concentration of tetanus antibodies decreases with age, and most people do not maintain protective antibody levels until 10 years after vaccination[5,9]. Therefore, TTCV vaccination and regular booster doses are necessary for sustained and effective immunity.

Characteristics Number of cases Composition ratio (%) Gender Male 122 51.69 Female 114 48.31 Age [years, M (IQR)] Male 56.00 (20.25) Female 67.00 (19.00) Occupation Farmer 160 67.80 Worker 26 11.02 Retiree 21 8.90 Laid-off or unemployed 14 5.93 Fisherman 6 2.54 Freelance 6 2.54 Children 2 0.84 Professional skill worker 1 0.42 Residence Urban 67 28.39 Rural 169 71.61 Tetanus toxoid vaccination Nil 216 91.53 Completed 20 8.47 Pathogenic factors Identified 211 89.41 Traumatism 191 80.93 Other risk factors 20 8.47 Unidentified 25 10.59 Injury sites Lower extremity 106 44.92 Upper extremity 63 26.69 Head and neck 31 13.14 Other sites 36 15.25 Incubation period [d, M (IQR)] Head and neck 5.00 (6.00) Trunk 30.00 (0.00) Upper extremity 7.00 (5.00) Lower extremity 9.50 (10.25) Multiple sites 7.00 (10.50) Initial diagnosis Yes 32 13.56 No 204 86.44 The level of health facilities for initial visit Province-level 101 42.80 City-level 67 28.39 County-level 44 18.64 Private/village 24 10.17 Time from onset to initial visit [d, M (IQR)] 2.00 (4.00) First symptoms Trismus 199 84.32 Muscle spasms 9 3.81 Myodynia 6 2.54 Nuchal rigidity 4 1.70 Dysphagia 4 1.70 Other symptom 14 5.93 Co-morbidities Yes 195 82.63 No 41 17.37 Complications Yes 195 82.63 No 41 17.37 Length of a hospital stay [d, M (IQR)] 16.00 (18.00) Hospitalization expenses [RMB, M (IQR)] 20,200.34 (3,659.10) Payment method Self-paying 131 55.51 Resident basic medical insurance 52 22.03 Rural cooperative medical insurance 43 18.22 Others 10 4.24 ICU admission Yes 61 25.85 No 175 74.15 Tracheal intubation or tracheotomy Yes 80 33.90 No 156 66.10 Table 1. Basic characteristics and clinical data of patients with non-neonatal tetanus

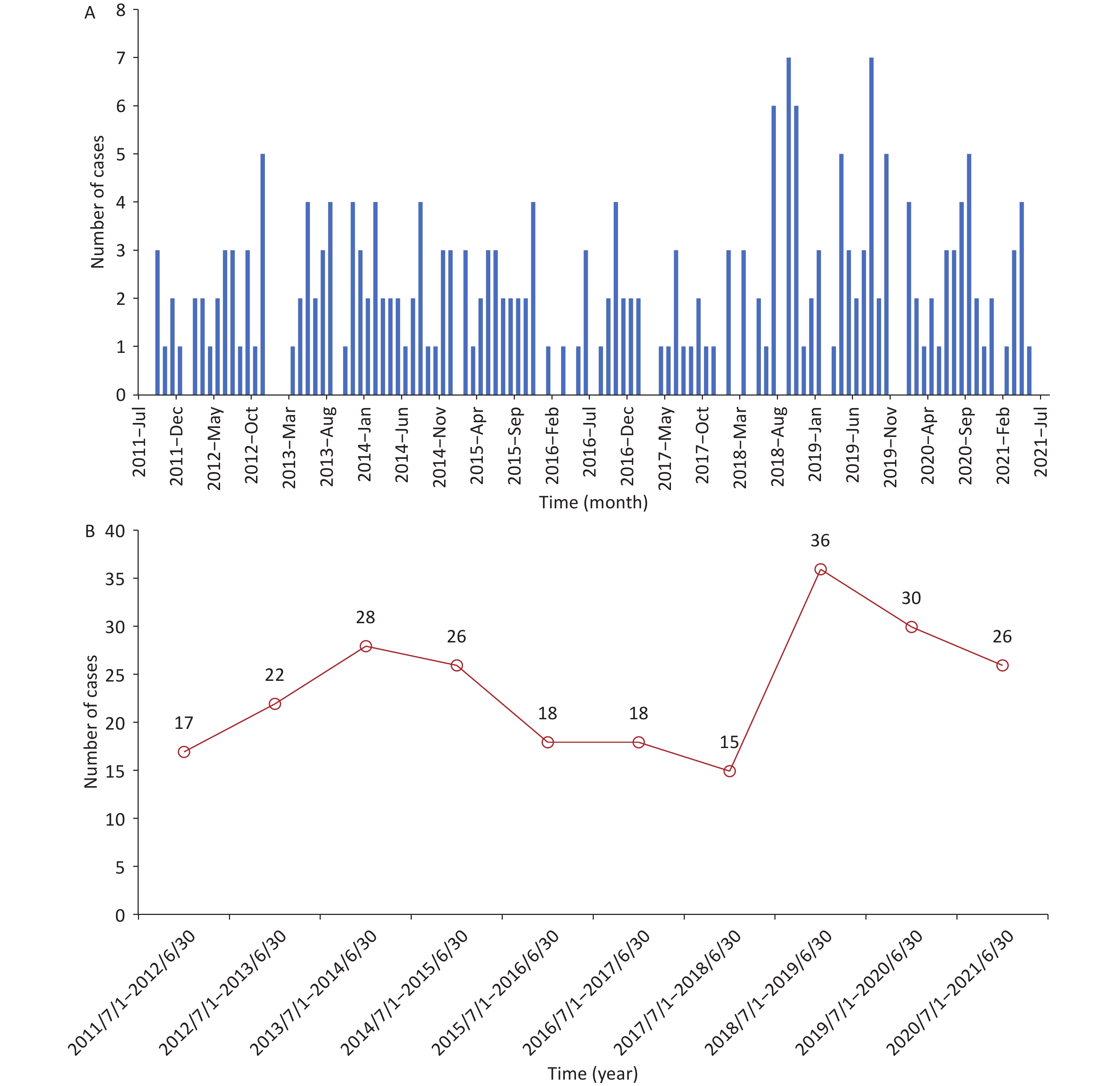

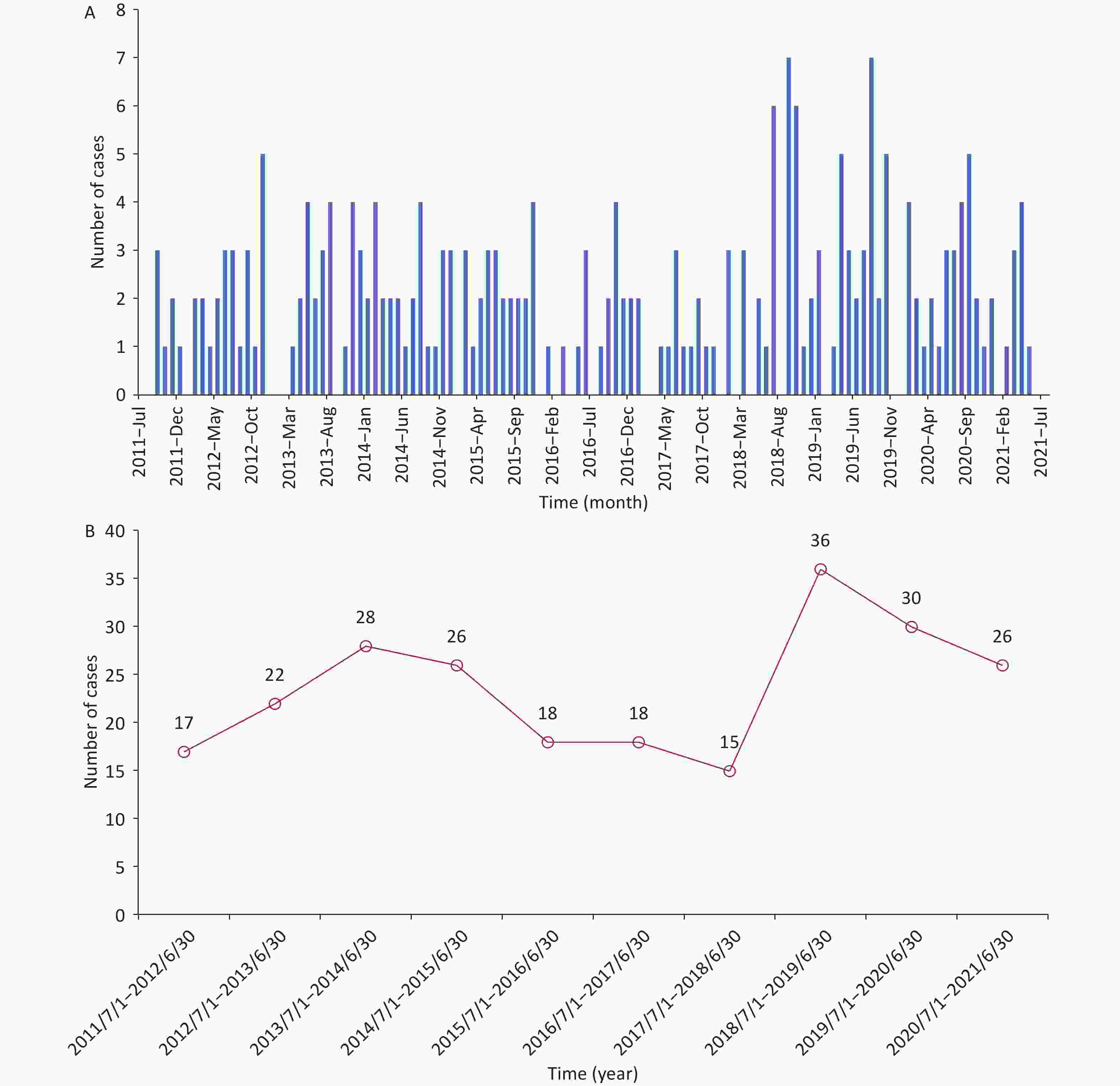

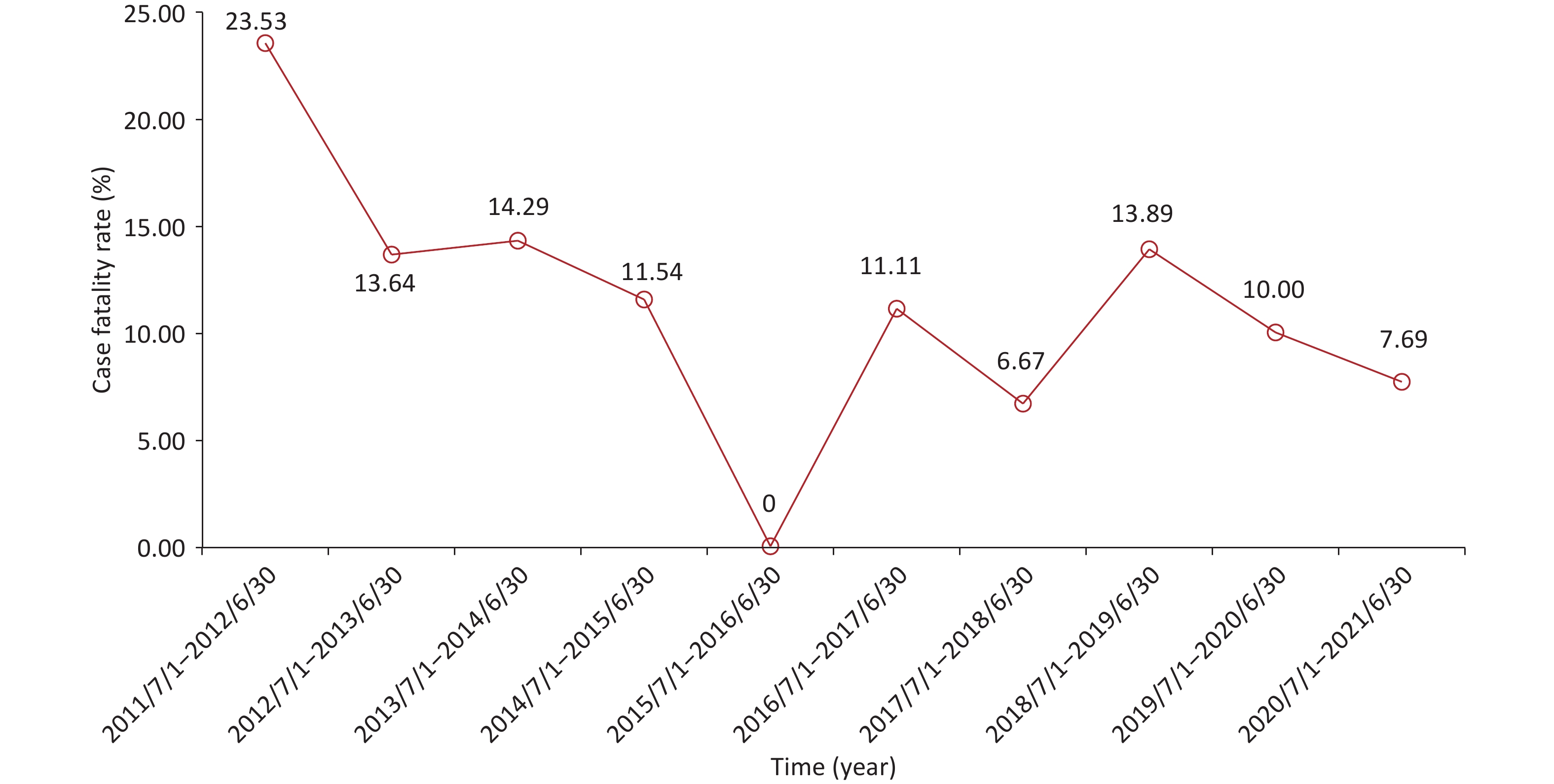

From July 2011 to July 2021, non-neonatal tetanus occurred almost every month, with sporadic onset and no seasonality (Supplementary Figure S1A, available in www.besjournal.com). The number of cases did not show a significant change in the annual disease occurrence (Supplementary Figure S1B). Among the 236 patients, the overall case fatality was 11.44% (n = 27). Except for the period from July 2011 to June 2012, the case fatality exceeded 20.00%, and the case fatalities in most of the other annual periods fluctuated between 6.00% and 15.00%, showing a downward trend (Figure 1). This can be attributed to the comprehensive coverage of vaccination and improvements in intensive care conditions[3].

Figure S1. Temporal distribution of non-neonatal tetanus cases from July 2011 to July 2021. (A) The time of disease onset of non-neonatal tetanus patients (month, year). (B) Trend in the number of non-neonatal tetanus cases over time (by year).

The pathogenic factors of the patients are shown in Table 1. Among the 236 patients, 211 (89.41%) cases had a clear pathogenic factor, while 25 (10.59%) cases did not specify a clear pathogenic factor. Among those with a clear pathogenic factor, 191 (80.93%) cases were caused by traumatic injuries. Other factors were oral infection, tumor rupture, drug injection, chronic skin ulcers, diabetic foot, indwelling gas cannula, minimally invasive surgery, and open surgery. Among the 191 trauma cases, 63 cases (26.69%) were cut wounds, 60 (25.42%) were puncture wounds, and 25 (10.59%) were fall injuries. In the diagnosis of tetanus, attention should be paid to the history of trauma and surgery and to other rare pathogenic factors to reduce clinical misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses[10].

The patients’ disease severity and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median incubation period was 8.00 days (IQR, 9.00 days), ranging from 1.00 day to 7.00 years for the 236 tetanus patients. There was a significant difference in the incubation period among different injury sites (P < 0.05), and the incubation period of injuries in the head and neck was shorter than that in the lower limb (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2, available in www.besjournal.com). The majority of cases presented typical initial symptoms, including trismus (84.32%), muscle convulsions (3.81%), muscle spasms (2.54%), stiff neck (1.70%), and dysphagia (1.70%). Of 236 patients, 32 cases (13.56%) were diagnosed for the first time, and 204 (86.44%) were not. The first diagnosis medical facilities were mainly at the county level (42.80%), city level (28.39%), and provincial level (18.64%), and a few were village level and private clinics. The time from onset to the initial visit ranged from 1.00 to 38.00 days, with a median of 2.00 days. Most patients (82.63%) had one or more co-morbidities and complications (Table 1). As shown in Supplementary Table S3 (available in www.besjournal.com) the most common co-morbidity was hypertension (10.17%), followed by tuberculosis (8.90%) and cerebrovascular disease (7.20%). The most common complication was secondary infection (67.37%), followed by respiratory failure (19.07%), electrolyte disturbances (16.10%), and hypoalbuminemia (14.41%). In combination with the fact that most of the patients came from rural areas, this indirectly reflects the inadequate level of medical care in primary healthcare facilities, the imperfections in intensive care, and the insufficient professional ability of medical staff.

Variables Head and neck Trunk Upper extremity Lower extremity Multiple sites χ2 value P value Incubation period [M (IQR)] 5.00 (6.00)a 30.00 (0.00) 7.00 (5.00) 9.50 (10.25) 7.00 (10.50) 18.39 < 0.01 Note. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare incubation period among different etiological sites. aCompared with lower limb group. Table S2. Comparison of latency at different etiological sites in non-neonatal tetanus patients

Characteristics Number of cases (persons) Composition ratio (%) Co-morbidities Hypertension 24 10.17 Tuberculosis 21 8.90 Cerebrovascular disease 17 7.20 Chronic liver disease 14 5.93 Coronary artery disease 7 2.97 Diabetes 7 2.97 Cancer 6 2.54 AIDS 6 2.54 Heart valve diseases 4 1.70 Autoimmune rheumatic disease 4 1.70 Arrhythmia 2 0.85 Complications Secondary infection 159 67.37 Respiratory failure 45 19.07 Electrolyte disturbances 38 16.10 Hypoalbuminemia 34 14.41 Hypohepatia 31 13.13 Myocardial injury 22 9.32 Autonomic dysfunction 16 6.78 Renal insufficiency 11 4.66 Asphyxia 9 3.81 Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy 8 3.39 Sepsis 7 2.97 Cardiac failure 5 2.11 Acute pancreatitis 5 2.11 Gastrointestinal hemorrhage 4 1.70 Coagulation dysfunction 4 1.70 Toxic encephalopathy 3 1.27 Acute myocardial infarction 3 1.27 Pressure ulcer 3 1.27 Thrombogenesis 2 0.85 Table S3. Co-morbidities and complications of patients with non-neonatal tetanus

According to the Ablett scale (Supplementary Table S1), 236 patients were divided into four groups: grade I (50 cases, 21.19%), grade II (110 cases, 46.61%), grade III (60 cases, 25.42%), and grade IV (16 cases, 6.78%). The proportion of patients with moderate and severe tetanus was higher than that reported in previous studies[10]. This may be attributed to the referrals from other hospitals, as patients with severe tetanus who cannot be adequately treated are typically transferred from lower-level hospitals to higher-level ones. Univariate analysis showed that there were significant differences in the time from onset to treatment, incubation period, forms of tetanus, combined diabetes, and cancer among different grading of disease severity groups (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Multivariate ordered logistic regression analysis showed that systemic tetanus (OR = 26.79, 95% CI: 9.24–77.63, P < 0.01) was the positive factor for the disease severity, and diabetes mellitus (OR = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.03–0.72, P = 0.02) was the negative factor for the disease severity (Table 2).

Variables Grading of disease severity Univariate analysis Multivariate

analysisGrade I, n (%) Grade II, n (%) Grade III, n (%) Grade IV, n (%) χ2 value P value OR (95% CI) P value Age [years, M (IQR)] 59.50 (19.25) 59.00 (21.25) 66.00 (19.25) 58.50 (23.50) 2.52 0.47 Time from onset to initial visit

[d, M (IQR)]3.50 (6.00) 3.00 (4.00) 2.00 (2.00) 1.00 (1.00) 16.43 < 0.01 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) 0.50 Incubation period [d, M (IQR)] 7.00 (9.00) 9.00 (11.00) 7.00 (5.00) 6.50 (10.00) 10.44 0.02 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) 0.07 Gender 0.16 0.98 Male 26 (21.31) 56 (45.90) 31 (25.41) 9 (7.38) Female 24 (21.05) 54 (47.37) 29 (25.44) 7 (6.14) Forms of tetanus 50.62 < 0.01 Localized/cerebral 22(81.48) 4 (14.82) 1 (3.70) 0 (0.00) 1.00 Systemic 28 (13.40) 106 (50.72) 59 (28.23) 16 (7.65) 26.79 (9.24, 77.63) < 0.01 Co-morbidities Chronic liver disease 1 (7.14) 9 (64.29) 3 (21.43) 1 (7.14) 2.36 0.47 Tuberculosis 5 (23.81) 8 (38.10) 7 (33.33) 1 (4.76) 1.20 0.76 Hypertension 3 (12.50) 11 (45.83) 8 (33.33) 2 (8.33) 1.88 0.60 Coronary artery disease 1 (14.29) 3 (42.86) 2 (28.57) 1 (14.29) 1.49 0.71 Heart valve diseases 2 (50.00) 0 (0.00) 2 (50.00) 0 (0.00) 4.88 0.13 Arrhythmia 0 (0.00) 1 (50.00) 1 (50.00) 0 (0.00) 1.68 1.00 Autoimmune rheumatic disease 1 (25.00) 2 (50.00) 1 (25.00) 0 (0.00) 0.65 1.00 Cerebrovascular disease 5 (29.41) 5 (29.41) 5 (29.41) 2 (11.77) 3.19 0.33 Diabetes 0 (0.0) 2 (28.57) 3 (42.86) 2 (28.57) 6.53 0.05 0.15 (0.03, 0.72) 0.02 Cancer 4 (66.67) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 2 (33.33) 13.57 < 0.01 3.32 (0.46, 23.81) 0.23 AIDS 0 (0.00) 3 (50.00) 2 (33.33) 1 (16.67) 2.78 0.35 Table 2. Risk factors on grading disease severity in non-neonatal tetanus patients

Patients were divided into two groups based on whether they survived (n = 209, 88.56%) or died (n = 27, 11.44%) (Supplementary Table S4, available in www.besjournal.com). Univariate analysis of risk factors for disease outcome showed that there were significant differences between the two groups in the time from onset to treatment, incubation period, tracheal intubation or tracheotomy, grading of disease severity, diabetes mellitus, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, secondary infection, respiratory failure, asphyxia, cardiac failure, myocardial injury, acute myocardial infarction, acute pancreatitis, and renal insufficiency (all P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S4). The above factors were then included in binary multivariate regression analysis showing that grading of disease severity (OR = 54.97, 95% CI: 5.55–544.15, P < 0.01), complicated with respiratory failure (OR = 14.19, 95% CI: 1.84–109.36, P = 0.01), complicated with asphyxia (OR = 84.18, 95% CI: 3.62–1,959.83, P < 0.01), cardiac failure (OR = 279.68, 95% CI: 4.31–18,140.28, P < 0.01), or renal insufficiency (OR = 84.45, 95% CI: 2.30–3,104.41, P = 0.02) were significantly associated with the risk of death in non-neonatal tetanus patients (Supplementary Table S5, available in www.besjournal.com), which is consistent with previous studies[5,8,10]. The care of tetanus patients will continue to present challenges in the future.

Variables Outcome χ2/Z value P value Died, n (%) Alive, n (%) Age [years, M (IQR)] 63.00 (23.00) 60.00 (20.00) −1.24a 0.22 Time from onset to initial visit [d, M (IQR)] 1.00 (1.00) 3.00 (4.00) −3.22a < 0.01 Incubation period [d, M (IQR)] 5.50 (7.00) 8.00 (10.00) −2.43a 0.02 Gender 0.18b 0.67 Male 15 (12.30) 107 (87.70) Female 12 (10.53) 102 (89.47) Forms of tetanus 2.77b 0.10 Systemic 27(12.92) 182 (87.08) Localized/Cerebral 0 (0.00) 27 (100.00) ICU admission 1.99b 0.16 No 17 (9.71) 158 (90.29) Yes 10 (16.39) 51 (83.61) Tracheal intubation or tracheotomy 18.10b < 0.01 No 8 (5.13) 148 (94.87) Yes 19 (23.75) 61 (76.25) Grading of disease severity 64.80b < 0.01 I 0 (0.00) 50 (100.00) II 1 (0.91) 109 (99.09) III 15 (25.00) 45 (75.00) IV 11 (68.75) 5 (31.25) Co-morbidities Chronic liver disease 1 (7.14) 13 (92.86) 0.01b 0.93 Tuberculosis 0 (0.00) 21 (100.00) 1.87b 0.17 Hypertension 2 (8.33) 22 (91.67) 0.03b 0.87 Coronary artery disease 1 (14.29) 6 (85.71) − 0.58 Heart valve diseases 0 (0.00) 4 (100.00) − 1.00 Arrhythmia 0 (0.00) 2 (100.00) − 1.00 Autoimmune rheumatic disease 0 (0.00) 4 (100.00) − 1.00 Cerebrovascular disease 3 (17.65) 14 (82.35) 0.19b 0.66 Diabetes 3 (42.86) 4 (57.14) − 0.03 Cancer 2 (33.33) 4 (66.67) − 0.14 AIDS 2 (33.33) 4 (66.67) − 0.14 Complications Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy 4 (50.00) 4 (50.00) − 0.01 Toxic encephalopathy 0 (0.00) 3 (100.00) − 1.00 Secondary infection 24 (15.09) 135 (84.91) 6.42b 0.01 Respiratory failure 21 (46.67) 24 (53.33) 68.10b < 0.01 Asphyxia 8 (88.89) 1 (11.11) 47.73b < 0.01 Cardiac failure 3 (60.00) 2 (40.00) − 0.01 Myocardial injury 6 (27.27) 16 (72.73) 4.40b 0.04 Acute myocardial infarction 2 (66.67) 1 (33.33) − 0.04 Gastrointestinal hemorrhage 0 (0.00) 4 (100.00) − 1.00 Acute pancreatitis 3 (60.00) 2 (40.00) − 0.01 Hypohepatia 6 (19.35) 25 (80.65) 1.40b 0.24 Renal insufficiency 7 (63.64) 4 (36.36) 25.86b < 0.01 Electrolyte disturbances 6 (15.79) 32 (84.21) 0.41b 0.52 Hypoalbuminemia 5 (14.71) 29 (85.29) 0.13b 0.72 Coagulation dysfunction 0 (0.00) 4 (100.00) − 1.00 Pressure ulcer 1 (33.33) 2 (66.67) − 0.31 Sepsis 2 (28.57) 5 (71.43) − 0.19 Thrombogenesis 0 (0.00) 2 (100.00) − 1.00 Note. aRepresents the Z values derived from Mann-Whitney U test. bRepresents the χ2 values derived from chi-squared test. Fisher’s exact probability test was used for the remaining variables. Table S4. Univariate analysis of risk factors of disease outcome in non-neonatal tetanus patients

Variables OR 95% CI P value Time from onset to initial visit 1.11 (0.91, 1.36) 0.30 Incubation period 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) 0.72 Tracheal intubation or tracheotomy 0.36 (0.02, 6.58) 0.49 Grading of disease severity 54.97 (5.55, 544.15) < 0.01 Diabetes 13.72 (0.61, 310.75) 0.10 Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy 0.44 (0.03, 6.51) 0.55 Secondary infection 0.12 (0.00, 19.36) 0.41 Respiratory failure 14.19 (1.84, 109.36) 0.01 Asphyxia 84.18 (3.62, 1,959.83) < 0.01 Cardiac failure 279.68 (4.31, 18,140.28) < 0.01 Myocardial injury 0.41 (0.02, 8.54) 0.56 Acute myocardial infarction 19.21 (0.04, 9,514.50) 0.35 Acute pancreatitis 8.60 (0.43, 172.56) 0.16 Renal insufficiency 84.45 (2.30, 3,104.41) 0.02 Table S5. Binary logistic regression analysis of risk factors for disease outcome in non-neonatal tetanus patients

The median length of hospital stay was 16.00 days (IQR, 18.00 days; range, 1.00–80.00 days). Self-payment (55.51%), resident basic medical insurance (22.03%), and rural cooperative medical insurance (18.22%) were the main payment methods (Table 1). The hospitalization cost ranged from RMB 733.10 to RMB 413,902.00 (~$107 − $60,188), with a median of RMB 20,200.34 (~$2,937). App one-fourth of the patients (25.85%) were admitted to the ICU, and the rate of tracheal intubation or tracheotomy was 33.90% (Table 1). There was a significant correlation between grading of disease severity and length of hospital stay (r = 0.28, P < 0.05), hospitalization expenses (r = 0.41, P < 0.05), ICU admission rate (r = 0.58, P < 0.05), and tracheal intubation or tracheotomy rate (r = 0.71, P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S6, available in www.besjournal.com). These data imply that tetanus treatment is both time-consuming and expensive, particularly for severe cases. Therefore, clinical treatments for non-neonatal tetanus must be optimized and enhanced to further reduce case fatality and disease burden.

Variables r value Length of hospital stay 0.28* Hospitalization expenses 0.41* ICU admission rate 0.58* Tracheal intubation or tracheotomy rate 0.71* Note. Spearman analysis was used for the correlation analysis. *P value < 0.05. Table S6. Correlation analysis of grading of disease severity in non-neonatal tetanus patients

One advantage of this study is that the data came from medical digital records, ensuring accuracy and reliability. Second, this study could fill the gap in China’s epidemiological and disease burden data. There are also some limitations in this study. The case investigation covered few medical facilities, resulting in a relatively small sample size. In addition, our results are based on a retrospective analysis of existing data, making it difficult to draw causative conclusions. In Guangxi, China, the incidence of non-neonatal tetanus has been sporadic during 2011–2021, with a relatively low case fatality, which reflects the relatively high level of local medical facilities and technologies for tetanus. Having no vaccination history may be an important factor in the incidence of non-neonatal tetanus. Systemic tetanus was an independent factor for the disease severity. Grading of disease severity, complications with respiratory failure, asphyxia, cardiac failure, or renal insufficiency were significantly associated with the risk of death in non-neonatal patients. These data and findings provide basic information for the prevention and clinical treatment of non-neonatal tetanus in China, highlighting the need for continued efforts in improving vaccine coverage.

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

The authors acknowledge all the participants and clinical/research staff from the Fourth People’s Hospital of Nanning, Guangxi International Zhuang Medical Hospital, and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University for their contribution to data collection.

Study concept and design: THM, YL, and LJY. Methodology: THM, ZXL, DSQ, and THL. Data collection: MGF, ZXL, YSX, and THL. Formal analysis and data curation: MGF, KYW, YZX, and MCY. Writing - original draft: KYW and MGF. Writing – review and editing: YL, THM, LJY, and KYW. All the authors listed have made substantial contributions to the work and approved it for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

HTML

23073+Supplementary Materials.pdf

23073+Supplementary Materials.pdf

|

|

Quick Links

Quick Links

DownLoad:

DownLoad: