-

An estimated 1.78 million adolescents aged 10–19 years and young adults aged 20–24 years develop tuberculosis (TB) every year, accounting for 17% of all new TB cases globally[1]. TB is considered a leading infectious cause of death globally among adolescents and young adults, although it is preventable and curable[2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2021, 1.2 million children and young adolescents developed TB and 209,000 died from the disease. However, only 15% of the targeted 115,000 children with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis/rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB/RR-TB) were treated between 2018 and 2022[3]. Some of the key challenges include difficulty in obtaining laboratory diagnosis of TB, particularly drug-resistant TB, among adolescents and young adults as well as a lack of suitable treatment regimens.

China has a high burden of TB and MDR-TB[4]. Although the implementation of TB control strategies has been effective in reducing the incidence of TB among Chinese children and adolescents over the years, it remains the most common bacterial infectious disease[5–7]. Because TB treatment has shifted from standardized regimens to more individualized ones, it has become increasingly important to collect information on drug resistance within specific populations[8]. A few studies in China, including ones conducted in Chongqing[9] and Shandong province[10], have evaluated the proportion of drug-resistant TB among young children. However, factors such as socioeconomic status, demographics, and access to medical care can impact the local epidemiology of drug-resistant TB, possibly limiting the generalizability of these site-specific results. Furthermore, characterization of drug-resistant TB in adolescents and young adults in large sample sizes or geographically diverse settings is lacking. Therefore, more rigorous evidence based on nationwide samples is needed.

Surveillance using routine drug susceptibility testing (DST) is the most effective method of monitoring drug-resistant TB. In 2005, China established a TB management information surveillance and monitoring system to address this issue. However, the accuracy of the prevalence of drug-resistant TB established via this surveillance depends on the results of rifampin susceptibility tests for at least 75% of new TB cases being registered. To assist China in developing national strategies to combat drug-resistant TB, a national drug-resistant TB survey system was established in 2007. This system included 70 clusters selected through a stratified cluster random sampling method. The information and isolates collected from patients were sent to the national TB reference laboratory for quality control and further analysis. More information on the survey’s design, information collection, laboratory testing, and quality control can be found in a previous study[11]. Based on detailed information and TB isolates gathered from the survey, we conducted a thorough analysis of drug resistance among adolescent and young adult patients with pulmonary TB. Our main objective was to provide an overview of the characteristics of drug-resistant TB and evaluate its trend over time.

-

This study was a retrospective analysis of drug-resistant TB among cases diagnosed with pulmonary TB between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2020. The participants were adolescents and young adults who were included in the 70 clusters of the national drug-resistant TB survey.

-

The anonymized data collected from the national drug-resistant TB survey included the following: year, sex, age, ethnicity, education level, history of household TB contact, previous TB treatment, category of TB, and results of phenotypic DST. Before analyzing the data for patterns and trends of drug resistance over time, it was carefully checked for both internal and external consistency.

-

DNA was extracted and purified from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) cultures using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method. The Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was utilized to prepare sequencing libraries, which were subsequently sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq X10 platform (Illumina, Inc.). The quality of the sequence reads was assessed using FastQC, (Babraham Bioinformatics, Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK) and paired-end reads were filtered using Trimmomatic[12]. The sequencing reads were then aligned to the M. tuberculosis H37Rv (GenBank accession number NC 000962.3) reference genome. Whole genome sequencing-based prediction of drug susceptibility was performed using TB profiler (version 3.0.8)[13,14], and lineage calls were made using the fast-lineage-caller version 1.0 software[15]. Further details about the whole genome sequencing and analysis can be found in a previous study[16].

-

Statistical analysis was performed using the software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables with normal distribution are presented using the mean and standard deviation; they were compared using Student’s t-test or Welch’s t-test. Categorical variables are presented as counts and proportions; these variables were compared using the pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. To analyze the time trends of phenotypic MDR-TB/RR-TB and rifampicin-susceptible, isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis (Hr-TB), newly diagnosed patients and those who were previously treated were not differentiated as adolescents or young adults. The time trends of drug-resistant TB and their significance were assessed using the Joinpoint regression program (version 4.9.1.0, National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). In brief, Joinpoint analysis estimates the overall trends in proportion, initially with no joinpoints, and tests for significant changes in the model with the sequential addition of joinpoints where a significant change occurs in the slope of the line. The annual percentage change for each period between joinpoints or average annual percentage change (AAPC) for the entire study period, with its 95% confidence interval (CI), was reported. The significance of the annual percentage change and or AAPC was tested using the Monte Carlo permutation method, and the annual percentage change and or AAPC was considered significant if its 95% CI did not include zero[17]. In this time trend analysis, the response variable was the natural logarithm of the drug-resistant proportion, and the independent variable used was the year of survey. Because of the small sample size, the analysis of concordance between phenotypic and genotypic DST results, lineages, and drug resistance-conferring mutations was not differentiated according to new and previously treated patients.

-

Adolescence was defined according to the WHO definition as the period between 10 and 19 years of age[18,19], and young adult was defined as the period between 20 and 24 years of age[1,20].

Pulmonary TB referred to any bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed case of TB involving the lung parenchyma or the tracheobronchial tree. A new case was defined as a newly registered episode of TB in a patient who had never received treatment for TB or who had taken anti-TB medication for less than 1 month. A previously treated patient was defined as a patient who had received anti-TB medication for 1 month or more in the past.

Hr-TB was defined as TB caused by M. tuberculosis strains resistant to isoniazid and susceptible to rifampicin. MDR-TB was defined as TB caused by M. tuberculosis strains that were resistant to at least both rifampicin and isoniazid. RR-TB was defined as TB caused by M. tuberculosis strains resistant to rifampicin; these strains may have been susceptible or resistant to isoniazid (i.e., MDR-TB) or to other TB medicines. Pre-extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (pre-XDR-TB) was defined as TB caused by M. tuberculosis strains that fulfilled the definition of MDR-TB and that were also resistant to at least one fluoroquinolone (either levofloxacin or moxifloxacin). Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) was defined as TB caused by M. tuberculosis strains that fulfilled the definition of MDR-TB and that were also resistant to at least one fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) and at least one additional group A drug (bedaquiline or linezolid)[21].

-

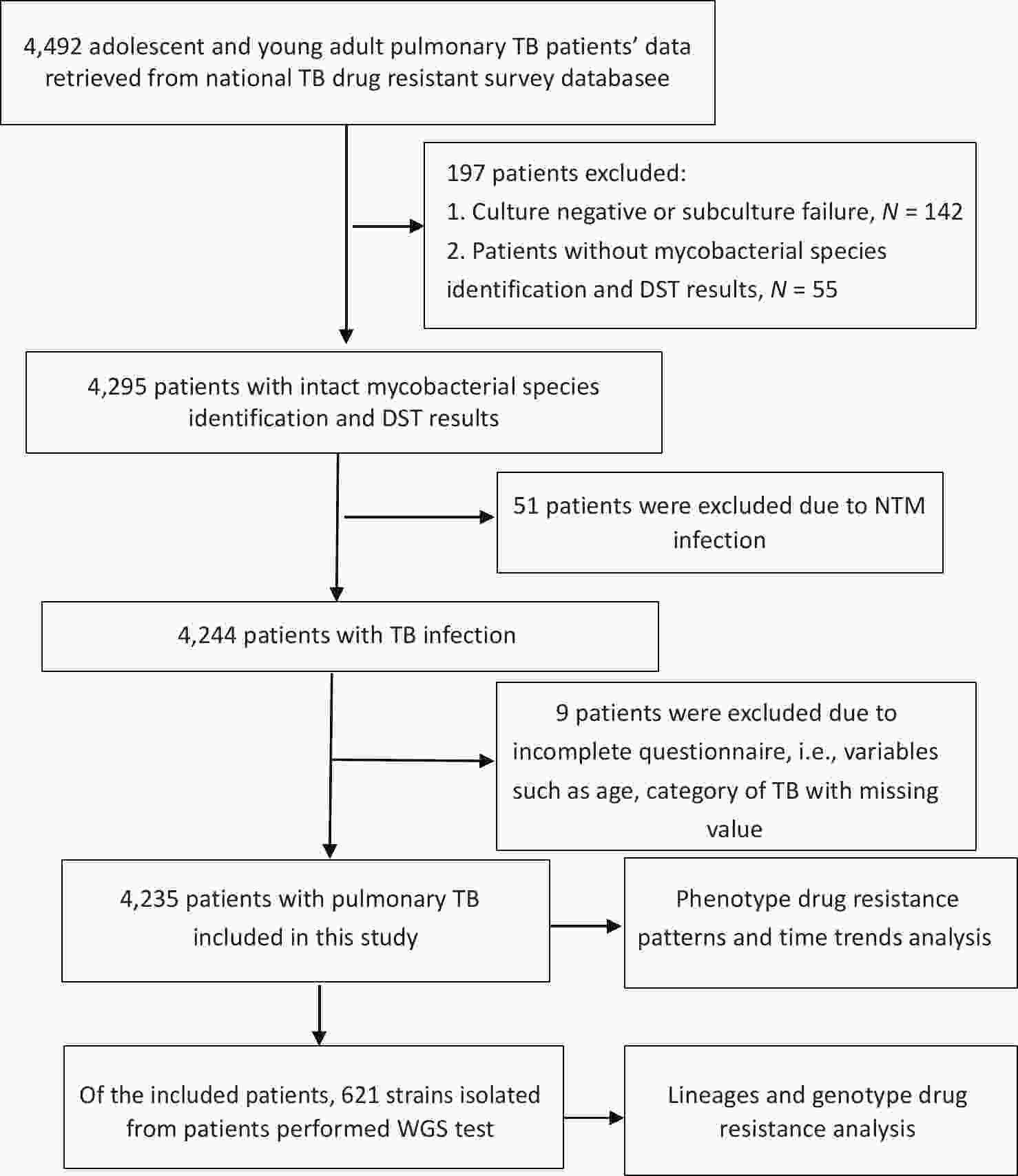

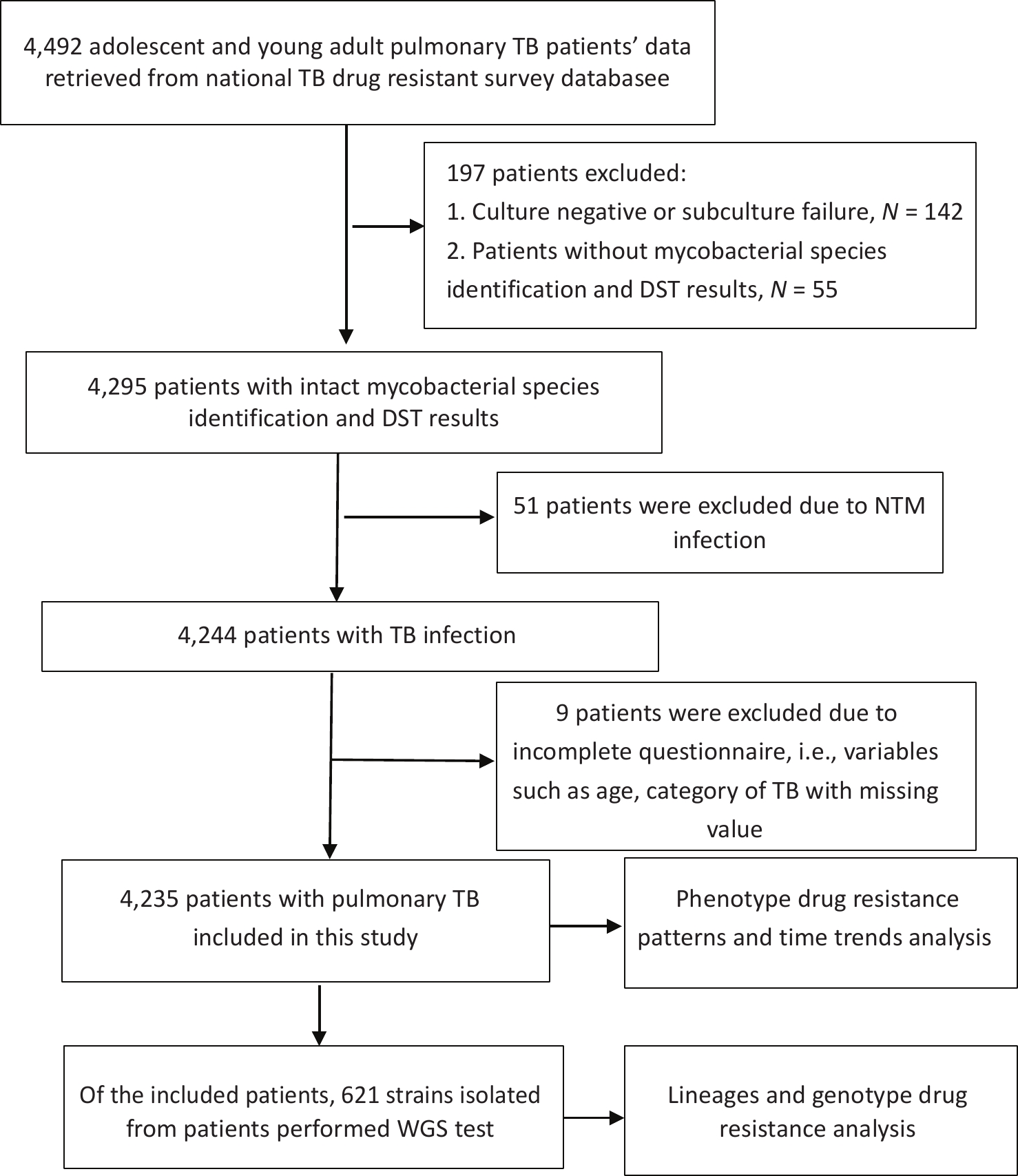

From 2013 to 2020, a total of 4,492 adolescent and young adult patients with pulmonary TB participated in the survey. Of these, 197 patients did not have DST results, including 142 patients with negative cultures or subculture failures, and 55 patients without mycobacterial species identification and DST results due to the laboratory testing failure. Fifty-one patients were excluded because they had nontuberculous infections, and nine were excluded because data on age or TB category was missing. Finally, 4,235 adolescent and young adult patients with pulmonary TB were included (Figure 1). The excluded patients were aged 20.09 (± 2.80) years, with 60.41% being male; therefore, no statistical difference in age and gender was observed between the excluded and included patients (P = 0.765 and P = 0.627, respectively). Of the included patients, 2,631 (62.1%) were male and 1,604 (37.9%) were female. The age of the patients ranged from 10 to 24 years, with a mean age of 20.15 (± 2.88) years. Among the patients, 1,686 (39.8%) were between 10 and 19 years old (adolescents) and 2,549 (60.2%) were between 20 and 24 years old (young adults). Of the total number of patients, 3,974 (93.8%) were newly diagnosed, and 261 (6.2%) had previously been treated for TB. The proportion of previously treated patients among the young adults (7.1%) was significantly higher than that among adolescents (4.7%; P = 0.002; Table 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the participants included in this study. TB: tuberculosis; DST: drug susceptibility testing; NTM: non-tuberculosis mycobacterium; WGS: Whole genome sequencing.

Characteristic Total cases no. (%) New cases no. (%) Previously treated patients no. (%) P value Sex Male 2631 (62.1) 2474 (94.0) 157 (6.0) 0.510 Female 1604 (37.9) 1500 (93.5) 104 (6.5) Age group in years Adolescents (10−19 years) 1686 (39.8) 1606 (95.3) 80 (4.7) 0.002* Young adults (20−24 years) 2549 (60.2) 2368 (92.9) 181 (7.1) Ethnic Han 3713 (87.7) 3492 (94.0) 221 (6.0) 0.313 Minority 508 (12.0) 469 (92.3) 39 (7.7) Unknown 14 (0.3) 13 (92.9) 1 (7.1) Education Illiterate/primary 254 (6.0) 237 (93.3) 17 (6.7) 0.034* Junior 1764 (41.7) 1632 (92.5) 132 (7.5) Senior 1433 (33.8) 1359 (94.8) 74 (5.2) College/university 752 (17.8) 715 (95.1) 37 (4.9) Unknown 32 (0.8) 31 (96.9) 1 (3.1) Residence Urban 1291 (30.5) 1218 (94.4) 73 (5.7) 0.272 Rural 2944 (69.5) 2756 (93.6) 188 (6.4) Household contact Yes 320 (7.6) 293 (91.6) 27 (8.4) 0.178 No 3821 (90.2) 3594 (94.1) 227 (5.9) Unknown 94 (2.2) 87 (92.6) 7 (7.4) Note. Data are presented as the counts (proportions). Asterisks indicate significant differences in the proportions of patients between new and previously treated patients (*P < 0.05). Table 1. Characteristics of adolescent and young adult with pulmonary tuberculosis by treatment history, 2013−2020 (n = 4,235)

-

The proportion of patients with drug-resistant TB was estimated for both new and previously treated patients, taking into account age category, gender, and where the patients resided. Among the 1,606 adolescents and 2,368 young adults who were newly diagnosed with TB, 4.61% (95% CI: 3.64–5.75) of adolescents and 5.11% (95% CI: 4.26–6.07) of young adults were found to have RR-TB, whereas 3.18% (95% CI: 2.37–4.15) of adolescents and 3.76% (95% CI: 3.03–4.60) of young adults had MDR-TB. Among the patients who were previously treated, 15.00% (95% CI: 8.00–24.74) of adolescents and 13.81% (95% CI: 9.14–19.71) of young adults had RR-TB, whereas 11.25% (95% CI: 5.28–20.28) of adolescents and 11.05% (95% CI: 6.88–16.55) of young adults had MDR-TB. The proportion of patients with RR-TB (6.98%; 95% CI: 5.61–8.56) and MDR-TB (5.25%; 95% CI: 4.07–6.66) was higher among those newly diagnosed with TB who were living in urban areas than among those living in rural areas (Table 2).

Age category New cases (n=3974) P value Previously treated patients (n=261) P value Adolescents (n=1606) Young adults (n=2368) Adolescents (n=80) Young adults (n=181) no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI Hr-TB 71 (4.42%, 95%

CI: 3.47−5.54)113 (4.77%, 95%

CI:3.95−5.71)0.6053 3 (3.75%, 95%

CI: 0.78−10.57)10 (5.52%, 95%

CI: 2.68−9.93)0.7598 RR-TB 74 (4.61%, 95%

CI: 3.64−5.75)121 (5.11%, 95%

CI: 4.26−6.07)0.4721 12 (15.00%, 95%

CI: 8.00−24.74)25 (13.81%, 95%

CI: 9.14−19.71)0.7998 MDR-TB 51 (3.18%, 95%

CI: 2.37−4.15)89 (3.76%, 95%

CI: 3.03−4.60)0.3281 9 (11.25%, 95%

CI: 5.28−20.28)20 (11.05%, 95%

CI: 6.88−16.55)0.9621 Sex Male (n=2474) Female (n=1500) Male (n=157) Female (n=104) no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI Hr-TB 121 (4.89%, 95%

CI: 4.07−5.82)63 (4.20%, 95%

CI: 3.24−5.34)0.3151 6 (3.82%, 95%

CI: 1.42−8.13)7 (6.73, 95%

CI: 2.75−13.38)0.2902 RR-TB 123 (4.97%, 95%

CI: 4.15−5.90)72 (4.80%, 95%

CI: 3.77−6.01)0.8081 19 (12.10%, 95%

CI: 7.45−18.25)18 (17.31%, 95%

CI: 10.59−25.97)0.2378 MDR-TB 87 (3.52%, 95%

CI: 2.83−4.32)53 (3.53%, 95%

CI:2.66−4.60)0.9778 15 (9.55%, 95%

CI: 5.45−15.27)14 (13.46%, 95%

CI:7.56−21.55)0.3254 Residence Urban (N=1218) Rural (n=2756) Urban (n=73) Rural (n=188) no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI no. % 95% CI Hr-TB 67 (5.50%, 95%

CI: 4.29−6.93)117 (4.25%,95%

CI: 3.52−5.07)0.0825 4 (5.48%, 95%

CI: 1.51−13.44)9 (4.79%, 95%

CI:2.21−8.89)0.8175 RR-TB 85 (6.98%, 95%

CI: 5.61−8.56)110 (3.99%, 95%

CI: 3.29−4.79)<0.0001* 13 (17.81%, 95%

CI: 9.84−28.53)24 (12.77%, 95%

CI: 8.35−18.40)0.2945 MDR-TB 64 (5.25%, 95%

CI: 4.07−6.66)76 (2.76%, 95%

CI: 2.18−3.44)<0.0001* 10 (13.70%, 95%

CI:6.77−23.75)19 (10.11%, 95%

CI: 6.20−15.33)0.4072 Note. Date are presented as the counts (proportions, 95% confidence interval). Hr-TB: Rifampicin-susceptible, isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis; RR-TB: Rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis; MDR-TB: Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to patients living in rural areas (*P < 0.05). Table 2. Proportion of new and previously treated patients with drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis according to age group, sex and residence

-

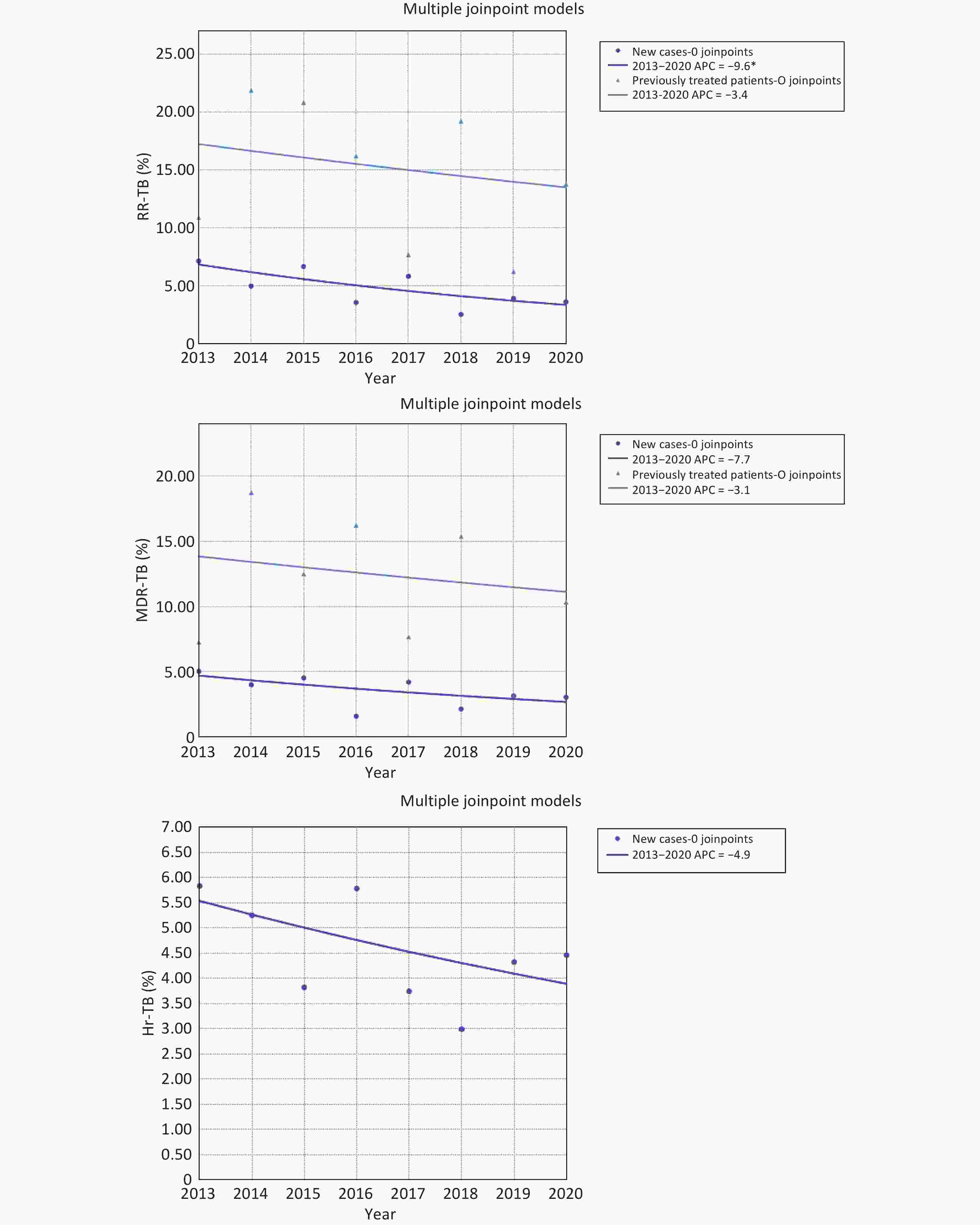

A significant decline was observed in the proportion of newly diagnosed patients with RR-TB (AAPC = −9.6%; 95% CI: −17.1 to −1.5; P = 0.028). The proportion of newly diagnosed patients with MDR-TB or Hr-TB remained stable, with AAPC values of −7.7% (95% CI: −16.5 to 2.0; P = 0.098) and −4.9% (95% CI: −11.2 to 1.8; P = 0.121), respectively, being noted. Among previously treated patients with TB, no significant decline in the proportion of patients with RR-TB or MDR-TB was observed, with AAPC values of −3.4% (95% CI: −17.3 to 12.8; P = 0.603) and −3.1% (95% CI: −19.9 to 17.2; P = 0.701), respectively, being noted. The trend of previously treated patients with Hr-TB could not be analyzed due to the small sample size (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Trends in drug resistance among new and previously treated patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, 2013-2020. Trends in RR-TB and MDR-TB among new and previously treated patients with pulmonary TB are shown in A and B, and trend in Hr-TB among new cases with pulmonary tuberculosis is shown in C.C. RR-TB: Rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis; MDR-TB: Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; Hr-TB: Rifampicin-susceptible, isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis; APC: Annual percentage change.

-

After analyzing 621 M. tuberculosis isolates using whole genome sequencing, we found that the isolates belonged to three different lineages, with lineage 2 (76.33%; 474/621) being the most prevalent. The other lineages identified were lineages 4 (23.51%; 146/621) and 1 (0.16%; 1/621). We found a strong correlation between phenotypic and genotypic resistance data for rifampicin (95.33%), isoniazid (92.27%), ethambutol (96.30%), kanamycin (98.71%), and ofloxacin (96.62%).

Of the 621 isolates, we identified 53 (8.53%) as RR-TB, 49 (7.89%) as Hr-TB, 46 (7.41%) as MDR-TB, and 17 (2.72%) as pre-XDR-TB. No XDR-TB isolates were identified. Among the 46 isolates identified as MDR-TB, 41 (89.13%) were lineage 2 and 5 (10.87%) were lineage 4. The most common mutations found among the MDR-TB isolates were Ser315Thr in the katG gene (71.74%; 33/46) and Ser450Leu in the rpoB gene (50.00%; 23/46).

Both lineages 2 and 4 showed evidence of drug-resistance mutations to rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, levofloxacin/moxifloxacin, para-aminosalicylic acid, kanamycin, bedaquiline, and clofazimine. Of the 620 isolates with lineages 2 and 4, 8.55% (53) had at least one resistance-conferring mutation in rpoB or rpoC for rifampicin, the most common mutation being Ser450Leu (50.94%; 27/53 isolates) in rpoB, with 47.83% (22/46) identified in lineage 2 and 71.43% (5/7) identified in lineage 4. For isoniazid, 15.32% (95/620) of isolates had at least one resistance-conferring mutation in genes katG, inhA, or ahpC. The predominant mutation was Ser315Thr in katG (64.21%; 61/95 isolates), with 62.79% (54/86) identified in lineage 2 and 77.78% (7/9) in lineage 4; the second most common mutation, C-777T in inhA, was detected in 18.95% (18/95) of isolates. For pyrazinamide, 3.87% (24/620) of isolates had one or more mutations identified in the pncA or panD genes, with a total of 22 different mutations identified; no predominant mutation was found. For ethambutol, 4.84% (30/620) of isolates had one or more mutations identified in the embA or embB gene, with the most common mutation being Met306Val (30.00%; 9/30 isolates) in embB. For ofloxacin/levofloxacin/moxifloxacin, 5.65% (35/620) of isolates had one or more mutations identified in the gyrA or gyrB genes, with the most common mutation being Asp94Gly (31.43%; 11/35 isolates) in gyrA. For para-aminosalicylic acid, 3.06% (19/620) of isolates had one mutation identified in the folC or thyA gene, with the most common mutation being His75Asn (73.68%; 14/19 isolates) in thyA. For kanamycin, 0.81% (5/620) of isolates had one mutation in the eis or rrs gene, with the most frequent mutation being A1401G (80.00%; 4/5 isolates) in rrs. Only one isolate with the mutation Ser68Gly in Rv0678 was identified for bedaquiline and clofazimine, respectively. No mutations were detected for either linezolid or cycloserine (Table 3).

Rifampicin Lineage2

(N = 474)Lineage4

(N = 146)Total

(N = 620)rpoB_1292 del_6_GCCAATT_G 1 0 1 rpoB_284ins_6_G_GGTCGAT; rpoB_His445Tyr 1 0 1 rpoB_Ala286Val; rpoB_Ser450Leu 1 0 1 rpoB_Asp435Val 1 0 1 rpoB_Glu360Gly; rpoB_Ser450Leu 1 0 1 rpoB_His445Arg; rpoB_Arg578Leu 1 0 1 rpoB_His445Asn; rpoB_Ile491Leu 1 0 1 rpoB_His445Asp 3 0 3 rpoB_His445Gln 0 1 1 rpoB_His445Gly 1 0 1 rpoB_His445Leu; rpoB_Pro969Ser 2 0 2 rpoB_His445Tyr 3 0 3 rpoB_Leu430Arg; rpoB_Asp435Gly 1 0 1 rpoB_Leu430Pro 3 0 3 rpoB_Leu430Pro; rpoB_Met434Ile 1 0 1 rpoB_Leu452Pro 2 1 3 rpoB_Pro280Ser; rpoB_Leu430Pro; rpoB_Asp435Gly; rpoB_His445Tyr 1 0 1 rpoB_Pro45Leu; rpoB_Ser450Leu 1 0 1 rpoB_Ser441Leu 1 0 1 rpoB_Ser450Leu 14 4 18 rpoB_Ser450Leu; rpoB_C-62T 1 0 1 rpoB_Ser450Leu; rpoB_Pro509Ser 0 1 1 rpoB_Ser450Leu; rpoB_Val534Met 1 0 1 rpoB_Ser450Leu;rpoC_Gly332Arg 1 0 1 rpoB_Ser450Leu; rpoC_Leu527Val 1 0 1 rpoB_Ser450Trp 1 0 1 rpoB_Thr399Ile; rpoB_Ser450Leu 1 0 1 Subtotal 46 7 53 No mutation 428 139 567 Total 474 146 620 Isoniazid katG_1448ins_3_A_AACG 1 0 1 katG_377ins_15_A_AAGCCGCCCCCGGCGC; katG_376ins_15_T_TGCCGCCCCCGGCGCC; katG_358ins_15_C_CGCCCCCGGCGCCGCT 1 0 1 katG_2del_3_ACAG_A 1 0 1 ahpC_C-54T 0 1 1 ahpC_C-81T 0 1 1 ahpC_G-48A 2 0 2 inhA_G-154A 1 0 1 inhA_C-777T 16 0 16 inhA_T-770C 1 0 1 katG_Ala379Val; katG_Ser315Asn 1 0 1 katG_Asp735Ala; ahpC_C-52T 1 0 1 katG_Gln127Pro; katG_Ser315Thr 0 1 1 katG_Ser315Asn 4 0 4 katG_Ser315Thr 53 6 59 katG_Gln461Arg 1 0 1 katG_Ser315Thr;inhA_C-777T 1 0 1 katG_Ala162Thr;inhA_C-777T 1 0 1 katG_Thr308Pro 1 0 1 Subtotal 86 9 95 No mutation 388 137 525 Total 474 146 620 Pyrazinamide panD_Ala128Ser 1 0 1 pncA_103del_6_GGTAGTC_G 1 0 1 pncA_116ins_1_G_GC; pncA_Ile5Thr 1 0 1 pncA_192del_11_ATAGTCCGGTGT_A 1 0 1 pncA_201del_10_CGACGAGGAAT_C 1 0 1 pncA_464del_1_AC_A 1 0 1 pncA_546ins_1_C_CA 0 1 1 pncA_A-11G 0 2 2 pncA_A-11G, pncA_Tyr34* 0 1 1 pncA_Ala143Thr 1 0 1 pncA_Asp136Gly 2 0 2 pncA_Asp49Ala 1 0 1 pncA_Asp63Ala 1 0 1 pncA_Cys72Tyr 1 0 1 pncA_Gly132Asp 1 0 1 pncA_Leu159Arg 1 0 1 pncA_Leu19Arg 1 0 1 pncA_Pro62Leu 1 0 1 pncA_Ser104Arg 0 1 1 pncA_Thr135Pro 1 0 1 pncA_Tyr34* 0 1 1 pncA_Val155Ala 1 0 1 Subtotal 18 6 24 No mutation 456 140 596 Total 474 146 620 Ethambutol embA_C-16G 2 0 2 embB_Arg257Trp 0 1 1 embB_Asp1024Asn 1 1 2 embB_Gln497Arg 1 0 1 embB_Gln497Arg, embB_Met306Ile 1 0 1 embB_Gly406Ala 5 0 5 embB_Gly406Ala, embA_C-16T 1 0 1 embB_Gly406Asp 1 0 1 embB_Gly406Asp, embB_Met306Ile 0 1 1 embB_Gly406Ser, embB_Met306Ile 1 0 1 embB_Met306Ile 3 1 4 embB_Met306Ile, embB_Asp1024Asn 0 1 1 embB_Met306Val 9 0 9 Subtotal 25 5 30 No mutation 449 141 590 Total 474 146 620 Ofloxacin / Levofloxacin / Moxifloxacin gyrA_Ala90Val 5 3 8 gyrA_Ala90Val, gyrA_Asp94Asn 0 1 1 gyrA_Ala90Val, gyrA_Asp94Ala 1 0 1 gyrA_Asp94Ala 3 0 3 gyrA_Asp94Asn 1 1 2 gyrA_Asp94Gly 9 1 10 gyrA_Asp94Gly, gyrA_Gly88Ala 0 1 1 gyrA_Asp94Tyr 2 0 2 gyrA_Leu109Val 1 0 1 gyrA_Ser91Pro 1 1 2 gyrB_Ala504Val 3 0 3 gyrB_Asp461Asn 1 0 1 Subtotal 27 8 35 No mutation 447 138 585 Total 474 146 620 Paraaminosalicylic_acid folC_Glu153Ala 1 0 1 folC_Ile43Ser 1 0 1 folC_Ser150Gly 2 0 2 thyA_Arg235Pro 1 0 1 thyA_His75Asn 14 0 14 Subtotal 19 0 19 No mutation 455 146 601 Total 474 146 620 Kanamycin eis_C-37A 1 0 1 rrs_A1401G 3 1 4 Subtotal 4 1 5 No mutation 470 145 615 Total 474 146 620 Bedaquiline Rv0678_Ser68Gly 1 0 1 Subtotal 1 0 1 No mutation 473 146 619 Total 474 146 620 Clofazimine Rv0678_Ser68Gly 1 0 1 Subtotal 1 0 1 No mutation 473 146 619 Total 474 146 620 Linezolid No mutation 474 146 620 Total 474 146 620 CycloSine No mutation 474 146 620 Total 474 146 620 Table 3. Drug resistance conferring mutations and main lineages among adolescent and young adult with pulmonary tuberculosis

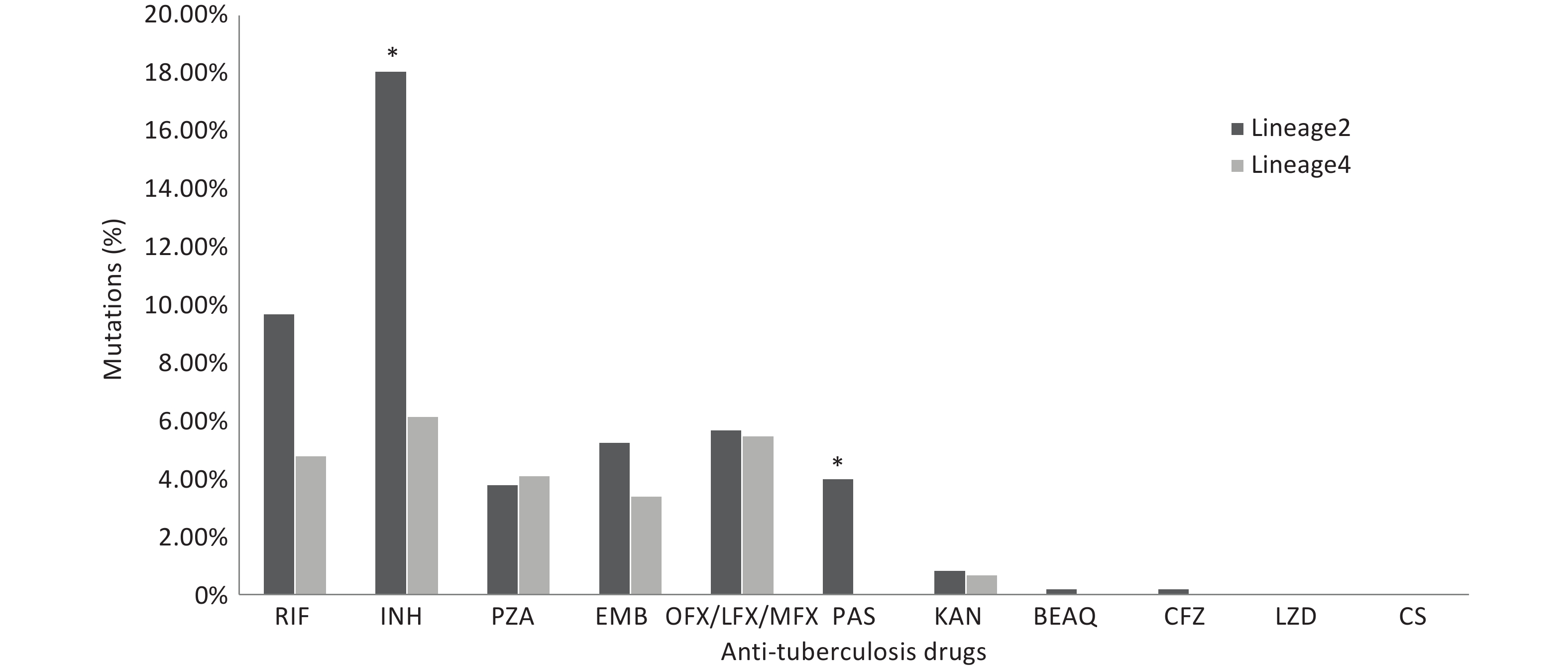

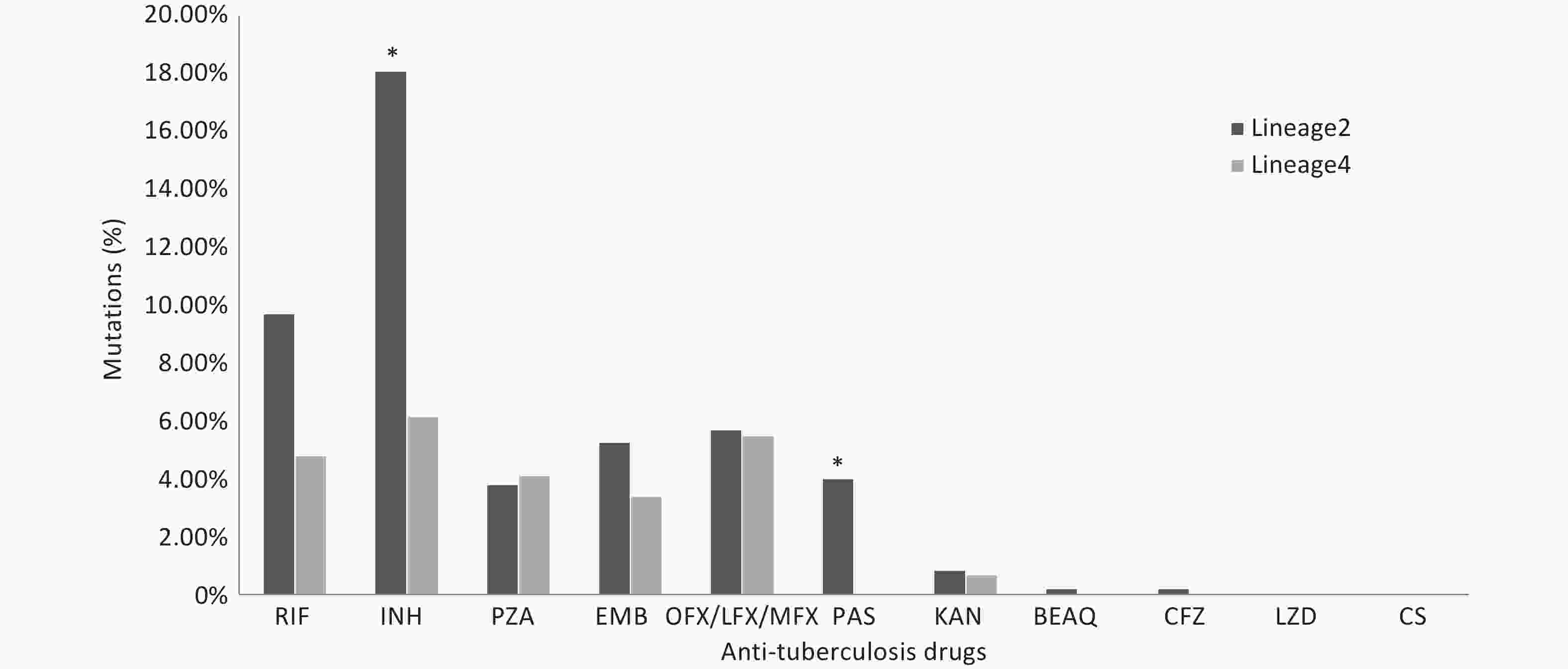

We compared the proportions of drug resistance-conferring mutations between lineages 2 and 4. The results revealed that the proportions of isolates with mutations conferring resistance to isoniazid and para-aminosalicylic acid were higher in lineage 2 (P < 0.05). The proportion of isolates with mutations conferring resistance to rifampicin was higher in lineage 2 than that in lineage 4; however, the difference was not statistically significant. The proportions of other anti-TB drug resistance-conferring mutations did not show statistical significance (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The proportions of drug resistance-conferring mutations between lineages 2 and 4. RIF: Rifampicin; INH: Isoniazid; PZA: pyrazinamide; EMB: Ethambutol; OFX: Ofloxacin; LFX: levofloxacin; MFX: Moxifloxacin; PAS: Para-aminosalicylic_acid; KAN: kanamycin; BEAQ: Bedaquiline; CFZ: Clofazimine; LZD: Linezolid; CS: CycloSerine. * Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to lineage 4 (*P < 0.05).

-

The results of this study showed that, among adolescents and young adults, MDR-TB accounted for between 3% and 4% of newly diagnosed cases, and approximately 11% of previously treated pulmonary TB cases. Among the new cases in the present study, the proportion of patients with MDR-TB was comparable to the pooled proportion of children with MDR-TB reported in a meta-analysis conducted in 2020[22], and this was higher than that reported in a study involving high-income countries[23]. However, this proportion was lower than those previously reported in studies conducted in Chongqing[9] and Shandong, China[10]. The high proportion of MDR-TB among new cases may indicate ongoing transmission of drug-resistant TB within the community[24].

The results of the current study revealed that 4%–5% of new TB cases were cases of Hr-TB. Isoniazid and rifampicin are key drugs used in standardized treatment regimens. Because diagnosis of drug-resistant TB in young patients is more challenging, bacteriologically confirmed TB and the results of DST are often not available before initiation of treatment. Moreover, information regarding the index case through which young people are infected may not always be available[25]; therefore, young patients are often treated with drug-susceptible TB regimens , which doctors deduce they are sensitive to the drugs used in the regimens. A previous study showed that treatment outcomes are significantly worse if patients are treated with a regimen comprising drugs that the bacteria are resistant to[26]. Our results highlighted that resistance to isoniazid should be tested before initiating treatment for TB to achieve optimal treatment outcomes.

The results of the present study showed a high proportion of MDR-TB/RR-TB among new cases from urban areas; this finding is in agreement with those of a study conducted in Ethiopia[27]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the TB burden in urban areas is high due to overcrowding and occupational transmission[28,29]. In high-burden TB settings, indoor or outdoor conditions of overcrowding proportionately increase the probability of contact with infectious patients with TB and contribute to ongoing transmission[30–35]. To reduce ongoing TB transmission, actively implementing case finding interventions, administering preventive therapy containing isoniazid to individuals with latent TB infections, and controlling infection remain key strategies. However, in South Africa, a study reported that increasing case finding interventions had no effect on the burden of TB at the community level[36], and the findings of another study suggested that implementing active case finding cannot control high levels of M. tuberculosis transmission unless conditions of overcrowding and poor ventilation are improved[37].

The association between ventilation, air movement in buildings, and the transmission of infectious disease such as M. tuberculosis was demonstrated in a systematic review[38]. A previous study demonstrated that poor ventilation is associated with an increased risk of TB infection[39]. Furthermore, existing evidence strongly supports the role of ventilation as a means of environmental control to reduce the risk of airborne transmission of M. tuberculosis[38,40]. Because it is an effective measure for controlling TB infection, the use of adequate ventilation has been widely proposed in infection control guidelines[41]. To reduce person to person transmission of M. tuberculosis in China, as a priority, research should focus on identifying effective strategies for controlling TB infection, improving understanding of where transmission occurs, and formulating reasonable interventions to interrupt transmission.

Preventing the emergence and transmission of drug-resistant TB and MDR-TB is an important focus of the national TB control program. In accordance with reports from the WHO, the present study revealed that the proportions of MDR-TB were relatively stable among new and previously treated patients aged 10–24 years between 2013 and 2020[3]. However, our study also showed a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of RR-TB among new cases. This declining trend could be the result of various factors, including the introduction and scale-up the WHO-recommended rapid diagnostics that test for rifampicin drug resistance in good time; this may be useful for the design of an optimal treatment regimen as well as to achieve favorable treatment outcomes, investigate people who have been in close contact with patients who are drug resistant, and properly implement active measures for infection control. For patients with TB who were previously treated, the proportion of MDR-TB/RR-TB showed no statistically significant declining trend. These findings emphasize the design of optimal treatment regimens, improvement of patient compliance, and judicious use of anti-TB drugs to treat MDR-TB/RR-TB effectively among previously treated patients.

The M. tuberculosis complex comprises nine lineages (lineages 1 to 9) based on whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphism[42]. Among these, lineage 2—also known as the East Asian lineage, mainly represented by the Beijing family—is associated with high virulence, increased transmissibility, and the spread of multidrug-resistant strains in diverse geographic regions[43,44]. Our findings revealed that lineage 2 was predominant among adolescents and young adults. This finding was similar to those of previous studies conducted in China and in neighboring countries[45,46]. Lineage 2 shows a higher proportion of drug resistance-conferring mutations than other lineages[46]. In the present study, the most common mutations identified in MDR-TB isolates were Ser315Thr (71.74%) in the katG gene and Ser450Leu (50.00%) in the rpoB gene. This finding was similar to those reported in other regions of China[47,48]. Most highly transmitted MDR-TB strains evolve over decades, gradually acquiring mutations that confer resistance to different antibiotic drugs[49]. The findings of a study conducted in South Africa indicated that the Ser315Thr mutation that confers resistance to isoniazid is the initial acquired mutation event for the subsequent evolution of MDR-TB strains[50]. Recently, a study demonstrated that the risk of acquiring resistance is higher in M. tuberculosis lineage 2 than in lineage 4; in that study, a higher hazard of rifampicin resistance evolving following isoniazid mono-resistance was estimated[51]. Resistance-conferring mutations are associated with different fitness costs: The drug resistance-conferring mutations katG S315T and rpoB S450L are mutations with low fitness cost[52,53]. However, the evidence for ongoing transmission of drug-resistant TB is promoted by co-selection of mutations in the bacteria[54]. The acquisition of compensatory mutations can partially or fully compensate for the loss of fitness, which has a significant role in the transmission of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis in human populations[55]. A recent study found that lineage 2 strains are heterogeneous and that the transmission advantage is restricted to certain clades of sublineage 2.3[56]. Consequently, identifying the phylogenetic clades of lineage 2responsible for the global expansion and understanding its phenotypic features is critical for developing effective strategies to prevent and control transmission.

Our study had several limitations. First, this study was based on national drug-resistant TB survey data, and we included bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB cases with available data on identification, phenotypic DST, and demographic information. Because diagnosis of drug-resistant TB in young patients is more challenging, some patients without DST results were excluded; therefore, the proportions of drug-resistant TB may have been underestimated. Second, because extrapulmonary TB is not a mandatory reported infectious disease in China, patients with extrapulmonary TB were not included; this may also have resulted in the burden of drug-resistant TB among adolescents and young adults in China being underestimated. Finally, although phenotypic DST results for isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, streptomycin, kanamycin and ofloxacin were available for the studied isolates, data for levofloxacin or moxifloxacin, bedaquiline, and linezolid resistance were not. Therefore, the phenotypic proportions of pre-XDR-TB and XDR-TB were not estimated.

-

The findings of this study revealed that the proportion of MDR-TB/RR-TB among adolescents and young adults in China was high, despite the proportion of RR-TB showing a declining trend among new cases. Lineage 2, with its high proportion of drug resistance-conferring mutations, was predominant among adolescents and young adults. The high burden of drug-resistant TB indicates that reevaluation of the current TB control strategy among adolescent and young adult patients with TB is urgently required. This reevaluation includes infection control, active case finding, and optimal treatment to ensure that the optimum strategy is implemented. The drug-resistant TB survey that focuses on adolescents and young adults should also be strengthened. Studies involving the emergence and transmission of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis are crucial for achieving control of drug-resistant TB in China.

Drug-Resistant Pulmonary Tuberculosis Among Adolescents and Young Adults in China

doi: 10.3967/bes2025.159

- Received Date: 2025-07-25

- Accepted Date: 2025-10-16

-

Key words:

- Adolescents /

- Young adults /

- Pulmonary tuberculosis /

- Drug resistance /

- Trend

Abstract:

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This study was a retrospective analysis of routinely collected survey data. Because we collected and analyzed data that was de-identified when it was recorded, the Ethical Review Board of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention approved the use of routinely collected data for this study (approval number 202223), and the need to obtain written informed consent was waived.

| Citation: | Shengfen Wang, Xichao Ou, Yang Zhou, Bing Zhao, Hui Xia, Yuanyuan Song, Ruida Xing, Yang Zheng, Yanlin Zhao. Drug-Resistant Pulmonary Tuberculosis Among Adolescents and Young Adults in China[J]. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences. doi: 10.3967/bes2025.159 |

Quick Links

Quick Links

DownLoad:

DownLoad: