-

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as glucose intolerance that begins or is first detected during pregnancy[1]. In 2021, GDM incidence in China was approximately 17.0%[2], and the pooled global standardized prevalence of GDM was 14.0%.[3] The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) predicted that the global incidence of GDM will continue to rise[3] GDM is a common condition during pregnancy and is associated with adverse short- and long-term outcomes in both mothers and their offspring[4,5]. Therefore, developing and implementing effective strategies to prevent and manage GDM is crucial.

The maternal diet plays an important role in GDM development[6-8]. Pregnant women experience significant metabolic and physiological changes that make them more nutritionally vulnerable. Globally, many pregnant women have a dietary intake that fails to meet their requirements for essential micronutrients[9]. To assess and promote women’s consumption of micronutrients, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations has proposed the Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDD-W) as an indicator, which has been shown to reflect one key dimension of dietary quality: micronutrient adequacy[10,11]. Promoting a diverse diet is an effective way to improve micronutrient intake and meet important nutritional needs. Some studies have indicated that dietary diversity reduces the risk of metabolic-related outcomes by improving the diversity of intestinal microbiota[12] and/or ensuring a wide range of bioactive compounds[13]. Previous studies have found that a greater variety in food group consumption is associated with a significantly lower risk of diabetes[14,15]. However, the effect of dietary diversity during pregnancy on the occurrence of GDM remains largely unexplored, and few studies have investigated this critical relationship. To identify effective measures for preventing GDM, the association between maternal dietary diversity during pregnancy and GDM risk was investigated using data from a cohort study.

-

The present study was embedded in the Tongji Maternal and Child Health Cohort (TMCHC), a prospective mother-offspring cohort study in Wuhan, Hubei Province, Central China, for which details have been previously published[16]. The first phase of this cohort study was conducted from January 2013 to May 2016, and follow-up data were collected throughout each pregnancy trimester. Pregnant women at 8–16 weeks of gestation were recruited and asked to complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained investigators to obtain information on lifestyle behaviors, dietary intake, and mental health during each trimester. All participants provided written informed consent upon enrollment, and the study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. 201302).

The current study recruited participants who completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) or 24-h dietary recall between the 12th and 26th weeks of gestation and underwent an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) at 24–28 weeks to diagnose GDM. Pregnant women were excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of diabetes, multiple gestations, unreliable dietary intake (energy intake < 500 or > 3500 kcal/d), or if they had completed the dietary assessment after the OGTT. Finally, 3026 women were included in the study (Supplementary Figure S1). A comparative analysis revealed no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the included and excluded subjects (Supplementary Table S1).

-

Data on dietary intake were collected using a face-to-face questionnaire. A 24-h dietary recall was used to assess all foods and beverages consumed on the previous day. Food models representing standard portion sizes and a color food photography atlas were used to improve the accuracy of the portion size estimates. A semi-quantitative FFQ was also used to collect dietary information. The semi-quantitative FFQ comprised 61 food items based on the nutrient composition and eating habits of Chinese individuals, covering over 200 types of food. This FFQ was validated in a subsample of TMCHC participants, demonstrating its reliability and validity for assessing food and nutrient intake among pregnant women in urban areas of central China.[17] For each item, the interviewee was required to recall the frequency of intake and portion size consumed during the last 4 weeks. In addition, daily energy intake was calculated in the dietary assessment based on the continuously updated China Food Composition Database[18].

-

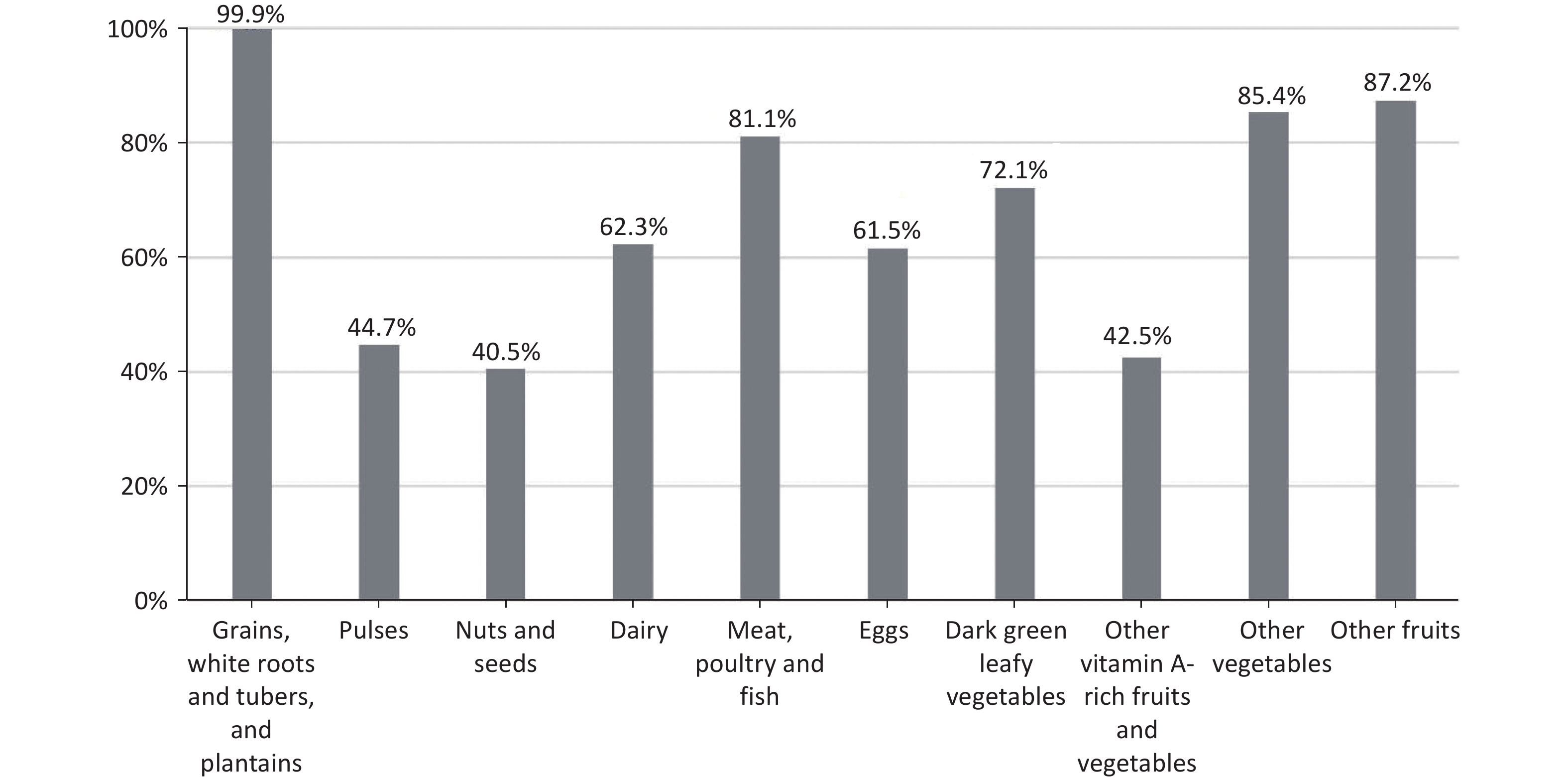

In the present study, the MDD-W score was used as an indicator of maternal dietary diversity.[19,20] According to the MDD-W guidelines released by the FAO,[10] all food items are categorized into 10 food groups, including: 1) grains, white roots, tubers, and plantains; 2) pulses (beans, peas, and lentils); 3) nuts and seeds; 4) dairy; 5) meat, poultry, and fish; 6) eggs; 7) dark green leafy vegetables; 8) other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; 9) other vegetables; and 10) other fruits. The original scoring criteria were designed for data collected using the 24-h recall method; participants received 1 point for each food group if their intake was ≥ 1 time/d.

Drawing on prior research, a scoring algorithm was adapted for the FFQ. First, the FFQ food items were classified into 10 food groups according to the MDD-W guidelines. Then, the intake frequencies of food items within each group were summed over the past four weeks to obtain the total intake frequency for each of the 10 food groups. Finally, the total intake frequency was divided by 28 to derive the daily intake frequency of each food group. A score of one was assigned to each food group with a combined daily frequency of at least once per day. The scoring criteria for the MDD-W are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The scores of all food groups were summed to form MDD-W scores, ranging from 0 to 10, with a higher score indicating greater maternal dietary diversity.

The criterion for meeting the MDD-W was the consumption of food from ≥ 5 of the 10 food groups[10]. Based on the minimum cutoff value recommended by FAO and the incidence of GDM at different MDD-W scores (Supplementary Table S3), MDD-W scores were categorized into three groups: ≤ 4, 5–7, and ≥ 8 to examine the dose-response relationship with GDM.

-

Participants underwent a 75 g, 2 h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after an overnight fast at 24–28 weeks of gestation to screen and diagnose GDM. According to the recommendations of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups,[21] GDM was diagnosed when any of the glucose values met or exceeded the following criteria: 1) fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.1 mmol/L; 2) 1 h plasma glucose ≥ 10.0 mmol/L; 3) 2 h plasma glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L.

-

Maternal demographics, socioeconomic status, and lifestyle information, including maternal age, ethnicity, self-reported pre-pregnancy weight, height, educational level, monthly average income per capita, parity, smoking and drinking habits during pregnancy, family history of the disease, and regular physical activity during pregnancy, were obtained using a structured questionnaire at enrollment. Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height in meters (m2) and was categorized according to the Chinese adult BMI classification as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–23.9 kg/m2), and overweight or obese (≥ 24.0 kg/m2), which was recommended by the Working Group on Obesity in China[22]. Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, which identifies the frequency and time spent walking and engaging in other moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activities during the previous 7 d. Regular physical activity was defined as moderate or vigorous intensity activity ≥ 30 min once with a frequency ≥ 3 times/wk. The gestational weeks at the time of the survey were calculated based on the maternal self-reported date of the last menstrual period and were confirmed or corrected in the first trimester by routine ultrasound examination. Gestational weight gain (GWG) before GDM diagnosis was calculated as maternal weight at OGTT minus the pre-pregnancy weight and was categorized according to the Standard of Recommendation for Weight Gain during Pregnancy Period as inadequate GWG, adequate GWG, and excessive GWG (EGWG)[23].

-

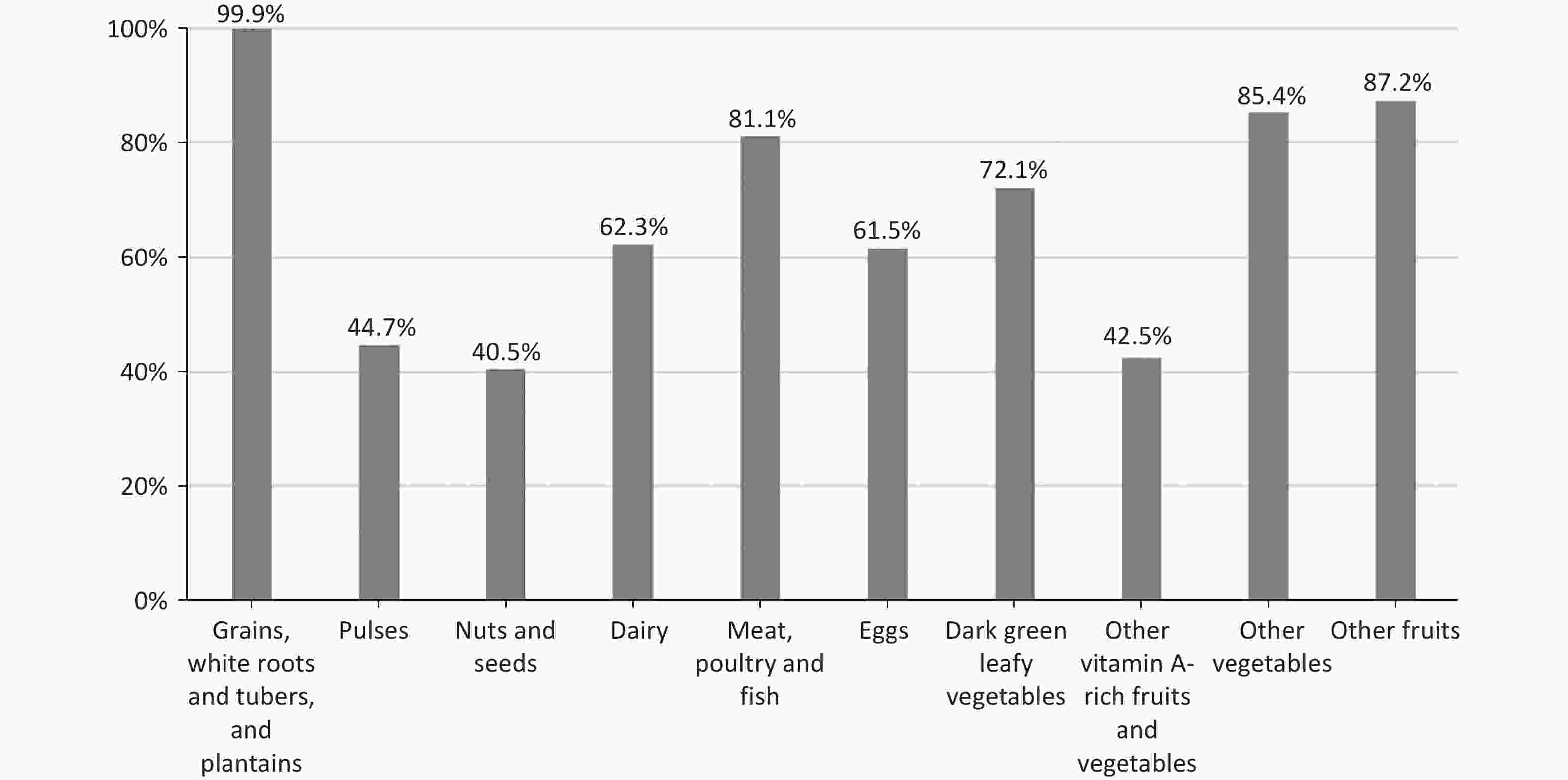

Demographic characteristics of the population were described by means ± standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. A bar chart was used to describe the distribution of MDD-W components.

A Poisson regression model was used to estimate relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of GDM risk related to maternal MDD-W score and the score for each food group. Model 1 was a crude model, and Model 2 was adjusted for maternal age (years), ethnicity, educational level (< 16 or ≥ 16 years), monthly average income per capita (< 5000 or ≥ 5000 Chinese yuan), pre-pregnancy BMI (< 18.5, 18.5–23.9, ≥ 24.0 kg/m2), parity (0 or ≥ 1), smoking habits (yes, no), drinking habits (yes, no), regular physical activity during pregnancy (yes, no) and family history of diabetes (yes, no). Model 3 was further adjusted for gestational age at survey (weeks), weight gain before GDM diagnosis (inadequate, adequate, and excessive), and total energy intake (kcal/d). In the analysis of the association between the score of each food group and the risk of GDM, Model 3 was additionally adjusted for the overall MDD-W score.

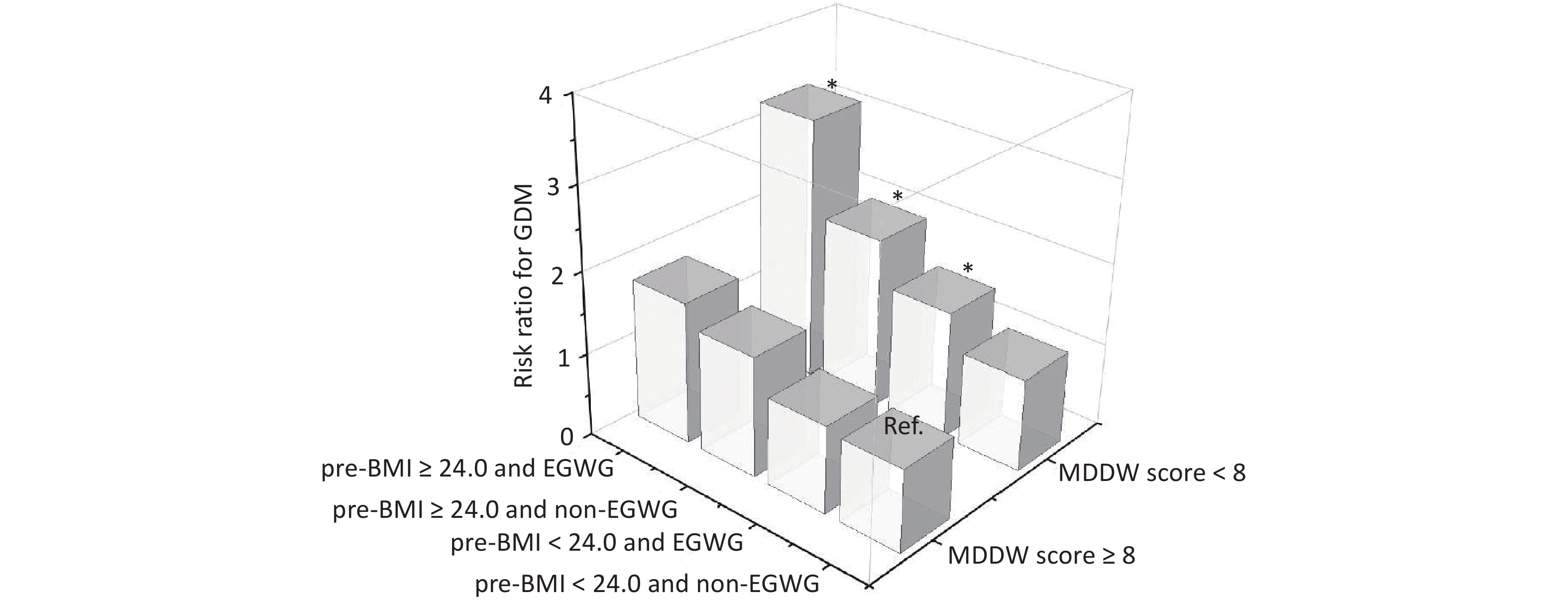

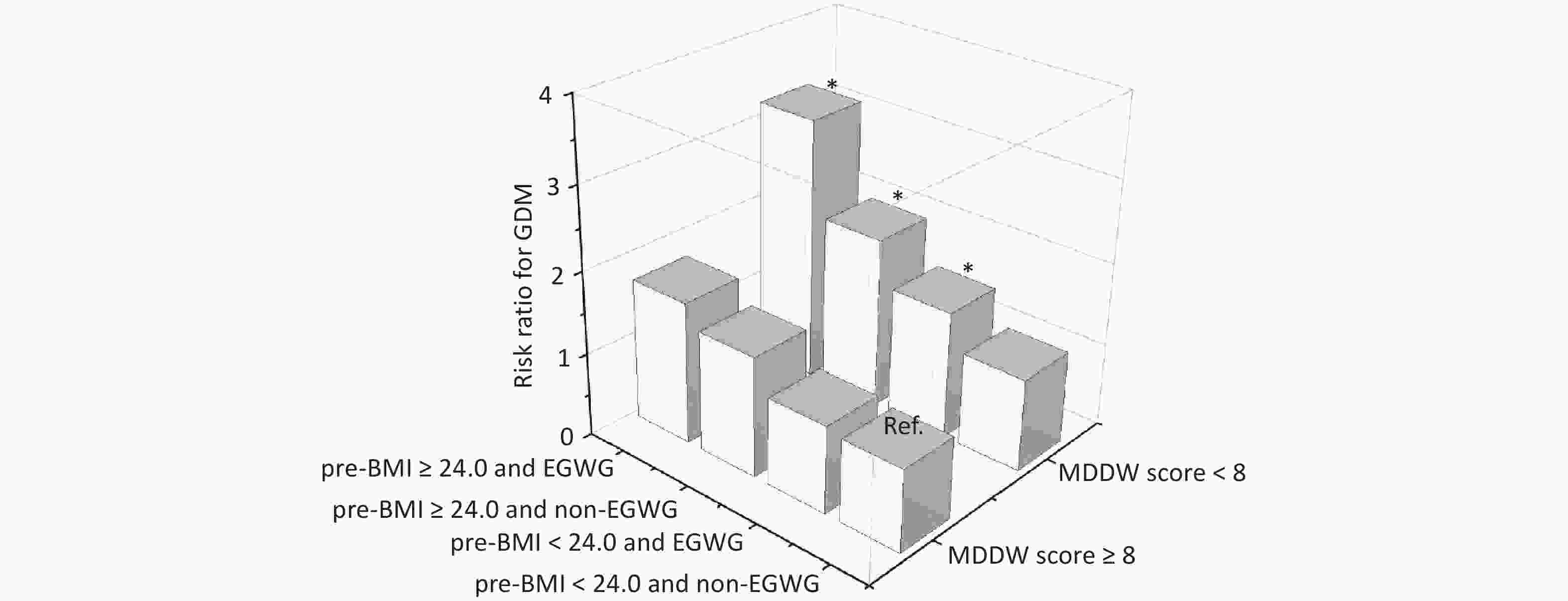

To further assess the potential influence of pre-BMI and GWG (both important risk factors of GDM) on the association between the MDD-W score and the risk of GDM, participants were assigned to four groups (pre-BMI < 24.0 and non-EGWG, pre-BMI < 24.0 and EGWG, pre-BMI ≥ 24.0 and non-EGWG, pre-BMI ≥ 24.0 and EGWG). Joint analysis and stratified analysis were conducted using Poisson log-linear regression model to estimate the RRs and 95% CIs for the association between pre-BMI, GWG, and MDD-W scores and the risk of GDM. To further assess the potential influence of different dietary assessments on the association between the MDD-W score and the risk of GDM, stratified analysis was performed to explore the association of the MDD-W score with the FFQ and 24-h dietary recall with GDM risk.

All statistical analyses were performed in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). Associations were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 using a two-tailed t-test.

-

In this study, the median MDD-W score was 7, with 329 (10.9%) participants having a score ≤ 4 and 1122 (37.1%) having a score ≥ 8. The basic characteristics of the participants according to their MDD-W scores are shown in Table 1. Their average age was 28.1 years, and the majority (97.8%) were of Han Chinese descent. Compared to the group with an MDD-W score ≥ 8, pregnant women in the groups with the MDD-W scores of 5–7 and ≤ 4 tended to have a lower educational level, lower family monthly income, and lower weight gain before GDM diagnosis, and to engage in less physical activity during pregnancy.

Overall MDD-W score ≤ 4 5–7 ≥ 8 N 3,026 329 1575 1122 Age (years) 28.1 ± 3.4 28.0 ± 3.2 28.0 ± 3.3 28.2 ± 3.4 Gestational week at survey (week) 20.5 ± 5.0 18.8 ± 5.2 20.2 ± 5.0 21.4 ± 4.7 Ethnicity, n (%) Han nationality 2958 (97.8) 320 (97.3) 1546 (98.2) 1092 (97.3) Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 617 (20.4) 61 (18.5) 321 (20.4) 235 (21.0) 18.5-23.9 2059 (68.0) 224 (68.1) 1073 (68.1) 762 (67.9) ≥ 24.0 350 (11.6) 44 (13.4) 181 (11.5) 125 (11.1) Educational level (years) ≥ 16 1675 (55.4) 137 (41.6) *** 826 (52.4) *** 712 (63.5) Monthly income per capita, CNY ≥ 5,000 1679 (55.5) 157 (47.7) *** 826 (52.4) *** 696 (62.0) Parity ≥ 1 385 (12.7) 40 (12.2) 218 (13.8) 127 (11.3) Smoking habit, n (%) yes 99 (3.3) 12 (3.7) 54 (3.4) 33 (2.9) Drinking habit, n (%) yes 43 (1.4) 5 (1.5) 22 (1.4) 16 (1.4) Pregnancy exercise, n (%) yes 659 (21.8) 58 (17.6) ** 315 (20.0) *** 286 (25.5) GWG before GDM diagnosis inadequate 404 (13.4) 71 (21.6) * 234 (14.9) * 99 (8.8) adequate 1247 (41.2) 139 (42.2) 657 (41.7) 451 (40.2) excessive 1375 (45.4) 119 (36.2) * 684 (43.4) * 572 (51.0) Note. MDD-W, minimum dietary diversity for women; BMI, body mass index; CNY, Chinese yuan; GWG, gestational weight gain; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus. Setting the MDD-W score ≥ 8 as the reference, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants.

-

Furthermore, the consumption rate of each food group among pregnant women was explored (Figure 1). Nearly all women reported consuming starchy staples at least once daily ( 99.0%). However, consumption of pulses, nuts and seeds, and other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables was low, with less than 70% of women with the MDD-W score ≥ 8 reporting intakes of foods from these groups, and only 13.1%, 7.6%, and 9.7% of women with the MDD-W score ≤ 4 reporting intakes from each group, respectively. (Supplementary Table S4)

-

Of the 3026 pregnant women, 357 (11.8%) were diagnosed with GDM. Table 2 illustrates the association between the MDD-W score and GDM risk. In the fully adjusted model (model 3), compared with participants whose MDD-W score was ≥ 8, those with a score of 5–7 had an increased risk of GDM (RR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.69) and those with a score ≤ 4 had a significantly higher risk of GDM (RR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.12, 2.26).

MDD-W score GDM, n (%) Model11 Model22 Model33 RR (95% CI) RR (95% CI) RR (95% CI) ≤ 4 53 (16.1) 1.75 (1.29, 2.39) 1.69 (1.24, 2.31) 1.58 (1.12, 2.26) 5–7 201 (12.8) 1.39 (1.11, 1.74) 1.39 (1.10, 1.74) 1.32 (1.03, 1.69) ≥ 8 103 (9.2) Ref. (1.00) Ref. (1.00) Ref. (1.00) Note. RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval; MDD-W, minimum dietary diversity for women; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus. 1 Model 1: crude model. 2 Model 2: adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, educational level, monthly average income per capita, pre-BMI, parity, smoking habits, drinking habits, regular physical activity during pregnancy and family history of diabetes. 3 Model 3: further adjusted gestational week at survey, weight gain before GDM diagnosis and total energy intake. Table 2. Association between maternal MDD-W score and the risk of GDM.

The association between each food group and the risk of GDM was also evaluated (Supplementary Table S5). Consuming dark green leafy vegetables < 1 time/d was associated with an increased risk of GDM (RR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.61), while no significant associations were observed for other food groups.

The combined effects of pre-BMI, GWG, and MDD-W on GDM were estimated and are shown in Figure 2. When the group with MDD-W score ≥ 8, pre-BMI < 24.0, and non-EGWG was set as the reference, among pregnant women with MDD-W score < 8, the adjusted RR (95% CI) for GDM was 1.14 (0.80, 1.61) for those with pre-BMI < 24.0 and non-EGWG, 1.46 (1.03, 2.08) for those with pre-BMI < 24.0 and EGWG, 2.04 (1.32, 3.16) for those with pre-BMI ≥ 24.0 and non-EGWG, and 3.18 (2.10, 4.81) for those with pre-BMI ≥ 24.0 and EGWG. Of note, an MDD-W score < 8 indicated a significantly increased risk of GDM, with the highest risk observed in those who were both overweight or obese before pregnancy and experienced excessive GWG. Furthermore, in the stratified analysis, pregnant women with MDD-W score < 8 were associated with a increased risk of GDM in pre-BMI ≥ 24.0 and EGWG (RR: 2.36; 95% CI: 1.18, 4.73) and pre-BMI < 24.0 and EGWG groups (RR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.02, 2.06, Supplementary Table S6). Stratified analysis of the association of the MDD-W score with the FFQ and 24-h dietary recall with GDM risk revealed similar findings (Supplementary Table S7).

Figure 2. The combined effects of pre-BMI, EGWG, and MDD-W on GDM. BMI, body mass index; EGWG, excessive gestational weight gain; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus. Risk ratios were calculated using the Poisson log-linear regression model and were adjusted for maternal age, ethnicity, educational level, monthly average income per capita, parity, smoking habits, drinking habits, regular physical activity during pregnancy, family history of diabetes, and gestational week at the time of the survey.

-

In this prospective cohort study, we observed that a lower MDD-W score, indicating a less diverse diet, was significantly associated with a higher risk of GDM, particularly among pregnant women who were overweight/obese before pregnancy or had experienced excessive weight gain before GDM diagnosis. Moreover, a higher consumption of dark green, leafy vegetables was inversely associated with GDM risk.

A greater diversity of consumed foods plays a specific role in health by influencing microbiota composition and ensuring a wide range of bioactive compounds[12,13]. These findings align with the results of several previous studies, which found that a greater diversity of consumed foods is associated with risk of metabolic-related outcomes. A previous study conducted in Western populations showed that a diet characterized by the regular consumption of all five food groups (dairy products, fruits, vegetables, meat and alternatives, and grains) is important for diabetes prevention[14]. A population-based study that included 16,117 Chinese adults suggested that a high dietary variety score calculated using 12 foods (whole grains, refined grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, nuts, red meat, poultry, processed meat, eggs, dairy products, and aquatic products) was associated with a low risk of new-onset diabetes[15]. To further examine the effect of dietary diversity during pregnancy on GDM occurrence, we used MDD-W, a tool proposed by the FAO to calculate maternal dietary diversity. We found that a higher MDD-W score was significantly associated with a reduced GDM risk. This study further confirmed that dietary diversity reduces GDM risk, a metabolic-related disease, during pregnancy and supports current public health recommendations encouraging a varied diet.

The criterion for meeting MDD-W is the consumption of food from ≥ 5 of the 10 food groups. However, this study indicates that the risk of GDM is significantly higher in groups with an MDD-W score < 8 compared to those with a score ≥8. This finding suggests that achieving a minimum level of dietary diversity may not be sufficient for pregnant women. Pregnant women may need to achieve a higher MDD-W score to accommodate the metabolic and physiological changes associated with pregnancy[21,25].

The potential biological mechanisms underlying the negative association between the MDD-W score and GDM risk may involve micronutrient intake. The MDD-W was proposed for adoption based on evidence that it is positively correlated with mean nutrient adequacy for 11 micronutrients (vitamin A, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, vitamin C, calcium, iron, and zinc).[11,26] Previous studies have linked decreased micronutrient intake during pregnancy to the development of GDM.[27,28] In addition to improved micronutrient intake, another mechanistic hypothesis centers on gut microbiota. Dietary exposures during pregnancy can influence the maternal gut microbiome, which has been suggested to play a crucial role in modulating insulin resistance.[29,30] Another possible mechanism by which dietary diversity may reduce GDM risk is through improved antioxidant status. A previous study found that the dietary diversity score is a proxy measure of blood antioxidant status in women, and that increasing dietary diversity is associated with a reduction in oxidative stress[31]. Moreover, oxidative stress has been linked to alterations in insulin sensitivity and endothelial adhesion molecule levels, which can further affect GDM development[32].

This study also suggests that lower consumption of dark green, leafy vegetables is associated with a higher GDM risk, consistent with the Nurses’ Health Study results, which revealed an association between the consumption of green leafy vegetables and a lower risk of diabetes in women[33]. This association may be due to the low energy density, low glycemic load, and high fiber and micronutrient content of dark green leafy vegetables[34]. Furthermore, a higher intake of dark green leafy vegetables can increase vitamin A and C intake, potentially improving insulin sensitivity, reducing maternal oxidative stress, and decreasing the risk of GDM[35-37]. In this study, only 31.0% of pregnant women in the group with an MDD-W score ≤ 4 consumed dark green leafy vegetables daily. Consumption rates of pulses, nuts and seeds, dairy, eggs, and vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables were < 30%. This highlights the need to enhance education and disseminate information regarding appropriate dietary practices during pregnancy, emphasizing the importance of a diverse and balanced diet.

Previous studies have shown that pre-pregnancy BMI and GWG are both important risk factors for GDM[38,39]. To assess the combined effects of high pre-pregnancy BMI and excessive GWG on GDM development, a joint analysis was conducted. We found a stronger negative association of the MDD-W score with GDM risk among women with a pre-pregnancy BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2, consistent with previous studies indicating that women with obese pre-pregnancy BMI demonstrated significantly lower diet quality than those with normal pre-pregnancy BMI[40,41]. This study also showed that among pregnant women with similar pre-pregnancy BMI categories, those who experienced excessive GWG were more susceptible to the effects of dietary diversity, underscoring the importance of addressing GWG during pregnancy, even among women with normal pre-pregnancy BMI. These findings suggest a synergistic effect of prepregnancy overweight/obesity, excessive GWG, and low dietary diversity during pregnancy on GDM risk. Furthermore, stratified analysis demonstrated that a diverse dietary intake was associated with a reduced risk of GDM, particularly among high-risk pregnant women with both prepregnancy overweight/obesity and escessive GWG.

This prospective cohort study investigated the association between dietary diversity during pregnancy and risk of GDM in a Chinese population. The prospective cohort study design allowed us to exclude the possibility of a reverse causality bias, providing strong evidence for an association between the MDD-W score and GDM. This prospective cohort study included a large sample size adjusted for many potential confounding factors. In addition, we explored the potential influence of pre-pregnancy BMI and GWG on the association between the MDD-W score and risk of GDM for identifying high-risk populations. Dietary patterns or single nutrients recommended by previous studies have certain limitations in terms of practical guidance; however, dietary diversity provides a more practical and operational approach, as assessed in the present study.

However, this study has several limitations. It included 772 women with a single 24-h dietary recall, which might have introduced random within-person errors. This might have attenuated these findings toward the null, given that we expected misclassification resulting from such measures to be non-differential with respect to the outcomes examined. Nevertheless, this is consistent with the FAO definition of MDD-W, which focuses on population-level interpretations rather than on day-to-day variability in individual intake[42]. In total, 2,254 women with MDD-W were assessed based on FFQ data, which were obtained by having participants recall their dietary intake over the past 4 weeks. However, a previous study has shown that the FFQ is a reasonably reliable and valid tool for assessing food and nutrient intake in pregnant women.[17] Stratified analysis of the association of the MDD-W score by the FFQ and 24-h dietary recall with GDM risk revealed similar findings. Moreover, although we adjusted for a comprehensive range of covariates in the analysis, residual confounding from unmeasured or unknown covariates, such as iron supplements, BMI trajectories, and Vitamin D, cannot be entirely ruled out.[43-45] Furthermore, this study was conducted among the Chinese Han population, and the findings may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups owing to potential differences in dietary patterns and lifestyles.

-

This study found that a lower MDD-W score, indicating less dietary diversity, was associated with a higher risk of GDM, particularly among women who were overweight/obese before pregnancy and experienced excessive GWG, emphasizing the importance of promoting dietary diversity among these high-risk groups.

Association between Dietary Diversity during Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study

doi: 10.3967/bes2025.160

-

Key words:

- Dietary Diversity /

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus /

- Pregnant Women /

- Cohort Study

Abstract:

The authors declare no competing interests.

The study received approval from the Ethics Review Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (No. 201302).

| Citation: | Weiming Wang, Qian Liang, Jin Liu, Chenfan Zhang, Yuhui Luo, Xuefeng Yang, Liping Hao, Nianhong Yang. Association between Dietary Diversity during Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study[J]. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences. doi: 10.3967/bes2025.160 |

Quick Links

Quick Links

DownLoad:

DownLoad: