-

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the third most common pathogen causing 10.6% of bacterial foodborne illnesses in China in 2021[1]. Heat-stable Staphylococcal Enterotoxins (SEs) produced by S. aureus are the main contributors to staphylococcal food poisoning (SFP), causing vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, headache, muscle cramps, and other acute gastroenteritis symptoms. More than 25 SEs and staphylococcal enterotoxin-like toxins (SEls) have been described and which together comprise a superfamily of pyrogenic toxin superantigens (SAgs)[2]. The classical enterotoxins (SEA-SEE) are reported to account for 95.0% of SFP[2]. Additionally, various virulence factors such as toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1), Panton-George leukocidin (PVL), and von Willebrand factor-binding protein (vWbp) play an important role in invasive S. aureus infections. Furthermore, the widespread use of antimicrobial agents in clinical treatment, animal husbandry, and other agricultural production practices has driven the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in S. aureus, which poses a significant threat to human health. This resistance trend leads to more serious infection consequences and higher mortality rates, particularly in clinical infections caused by multi-drug resistance (MDR) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

In recent years, sushi has gained increasing popularity in China and worldwide because of its convenience and nutritional value. According to the New Catering Big Data of China, the number of catering enterprises focusing on sushi in China will exceed 19,500 by 2022. However, as a type of ready-to-eat (RTE) food, sushi products may serve as potential vehicles for the transmission of food-borne bacterial hazards[3], primarily because of the complex manual handling processes and cross-contamination from raw materials. S. aureus is one of the most commonly isolated bacteria from sushi products, with global prevalence rates ranging from 16.7% to 26.0%[4,5], and is the major cause of SFP outbreaks[3]. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the prevalence and genetic characteristics of S. aureus in sushi will facilitate the assessment of food safety risks and formulation of corresponding monitoring, prevention, and control strategies, thereby safeguarding public food safety.

Currently, there are limited published data characterizing S. aureus contamination of sushi in China. In this study, we systematically investigated the antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular characteristics of S. aureus isolates from sushi products in China. Using whole-genome sequencing, we identified the associated antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genotypes, enterotoxin genes, and prevalent sequence types (STs). These findings reveal the unique features of this pathogen and provide critical insights into risk assessment models and food safety control strategies for S. aureus in sushi products within the Chinese market.

In this study, 54 S. aureus isolates were collected from commercially available sushi products across 19 provinces in China between 2020 and 2021 as part of a surveillance program conducted by the National Health Commission Key Laboratory of Food Safety Risk Assessment. Sample collection, storage, and transportation were performed in accordance with GB 4789.1-2016. The isolates were collected following GB 4789.10-2016 and further confirmed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The reference strain S. aureus ATCCTM29213 was included as a quality control throughout the experiments.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was performed using the microbroth dilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (29th Edition: M100). A panel of 11 antimicrobials commonly used in veterinary and human medicine was tested: penicillin (PEN), oxacillin (OXA), cefoxitin (CFX), tetracycline (TET), erythromycin (ERY), clindamycin (CLI), ciprofloxacin (CIP), gentamicin (GEN), linezolid (LZD), chloramphenicol (CHL) and vancomycin (VAN). The breakpoints for the resistance interpretation rates are presented in Table 1. The concordance between antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and genotypes was calculated using the following formula: phenogenotypic (PG) concordance = (P1G1 + P0G0)/total number of isolates, where P1G1 refers to phenotypically resistant and genotypically positive isolates (P1G1), whereas P0G0 refers to phenotypically susceptible and genotypically negative isolates (P0G0).

No. Antimicrobial Interpretive Categories and MIC Breakpoints, µg/mL Number of isolates (percentage, %) S I R S I R 1 Penicillin (PEN) ≤ 0.12 ≥ 0.25 12 (22.2%) 0 (0%) 42 (77.8%) 2 Erythromycin (ERY) ≤ 0.5 1–4 ≥ 8 39 (72.2%) 0 (0%) 15 (27.8%) 3 Tetracycline (TET) ≤ 4 8 ≥ 16 46 (85.2%) 5 (9.3%) 3 (5.6%) 4 Cefoxitin (CFX) ≤ 4 ≥ 8 51 (94.4%) 0 (0%) 3 (5.6%) 5 Oxacillin (OXA) ≤ 2 ≥ 4 51 (94.4%) 0 (0%) 3 (5.6%) 6 Clindamycin (CLI) ≤ 0.5 1−2 ≥ 4 51 (94.4%) 0 (0%) 3 (5.6%) 7 Ciprofloxacin (CIP) ≤ 1 2 ≥ 4 48 (88.9%) 4 (7.4%) 2 (3.7%) 8 Gentamicin (GEN) ≤ 4 8 ≥ 16 52 (96.3%) 1 (1.9%) 1 (1.9%) 9 Linezolid (LZD) ≤ 4 ≥ 8 53 (98.1%) 0 (0%) 1 (1.9%) 10 Chloramphenicol (CHL) ≤ 8 16 ≥ 32 54 (100%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 11 Vancomycin (VAN) ≤ 2 4–8 ≥ 16 54 (100%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) Note. S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration. Table 1. The interpretive categories and MIC breakpoints and results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing against 11 antimicrobials

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed using an Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform (Illumina Inc., USA) at Shanghai Majorbio Biopharm Technology Co., Ltd. Raw sequencing reads were quality-filtered using Trimmomatic v0.39 and fastp version 0.20.0, assembled with SOAPdenovo v2.04, and annotated using Prokka v1.14.5. Antibiotic resistance-encoding genes (ARGs) and virulence factor genes were identified using ResFinder v2.1 and the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB), respectively. All these genes were screened using the BLASTN algorithm, with minimum nucleotide identity of 80.0% and alignment length coverage of 80.0%. In silico multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis was performed by aligning seven housekeeping genes (arcC, aroE, glpF, gmk, pta, tpi, yqiL) with MLST characterized according to PubMLST database. Noval alleles identified in this analysis were submitted to a database for annotation purposes. Core genome analysis was performed using Roary v3.11.2, and Mafft v7.3.13, for multiple sequence alignments. Core single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis was performed using the Snippy pipeline (v4.6.0). A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed, and then visualized and annotated using tvBOT.

Among the 54 S. aureus isolates, 43 (79.6%) were resistant to one or more antimicrobial agents, 5 (9.3%) were MDR, and 3 (5.6%) were MRSA. The overall resistance and MDR rates were lower than those of isolates from foods of animal origin such as raw fish (88.5%, 30.0%)[6] and meat products (98.7%, 94.6%))[7]. The highest resistance rate was observed for penicillin at 77.8% (42/54), followed by erythromycin (27.8%, 15/54), and then tetracycline, cefoxitin, oxacillin, clindamycin (5.6%, 3/54 each), ciprofloxacin (3.7%, 2/54), gentamicin (1.9%, 1/54), and linezolid (1.9%, 1/54) (Table 1). All the isolates were susceptible to chloramphenicol and vancomycin. Tetracycline resistance is generally regarded as a livestock-associated marker. Reportedly, the tetracycline resistance rates of S. aureus isolates from raw meat and fish are 54.7% and 36.5%[6,7], respectively. Conversely, the significantly lower tetracycline resistance rate (5.6%) observed in this study suggests that livestock-associated ingredients may not be the primary source of S. aureus in sushi. A total of 11 distinct resistance profiles were identified, with the most prevalent resistant profiles in the cohort being penicillin (40.7%, 22/54), penicillin-erythromycin (16.7%, 9/54), penicillin-oxacillin-cefoxitin (5.6%, 3/54) (Figure 1A).

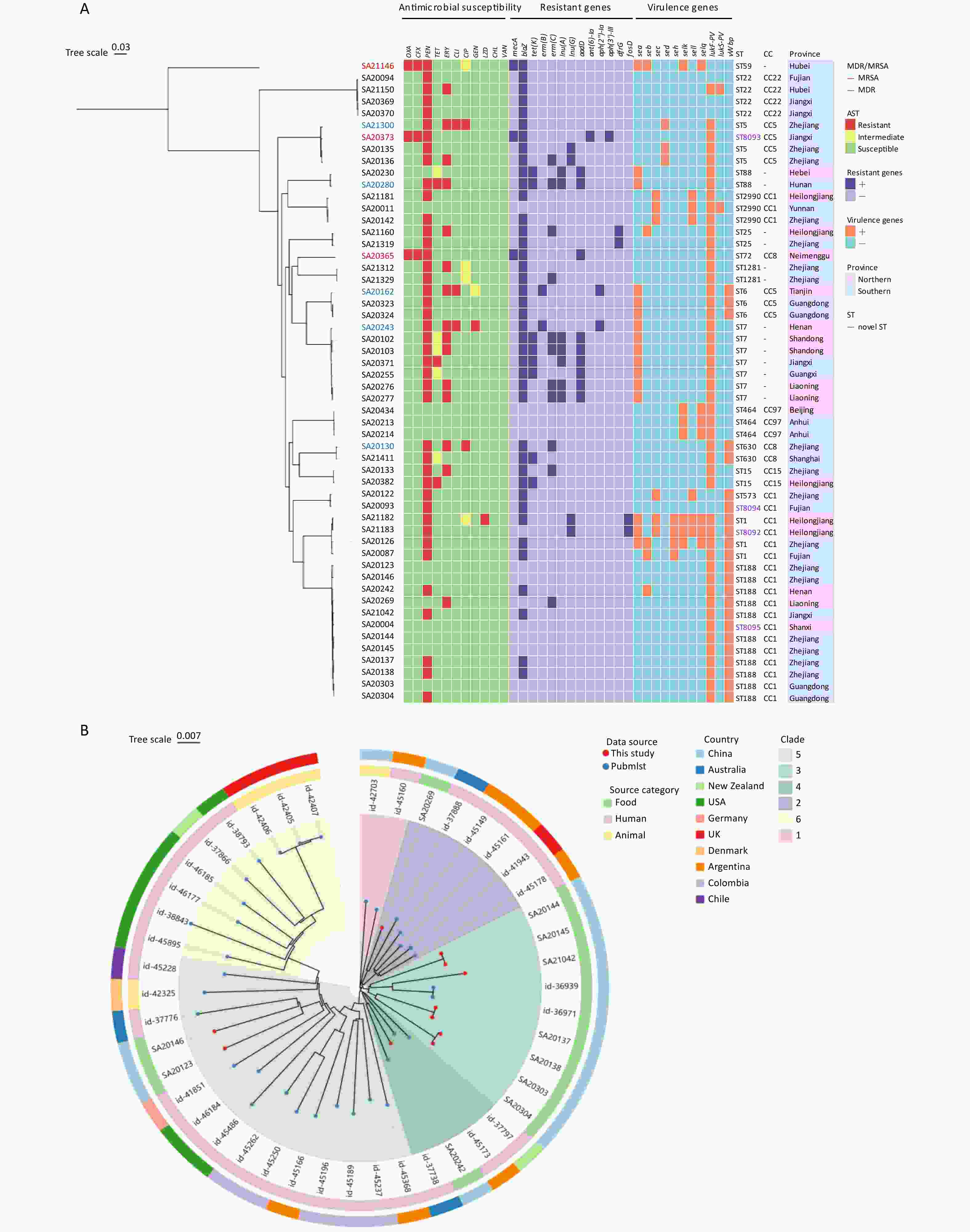

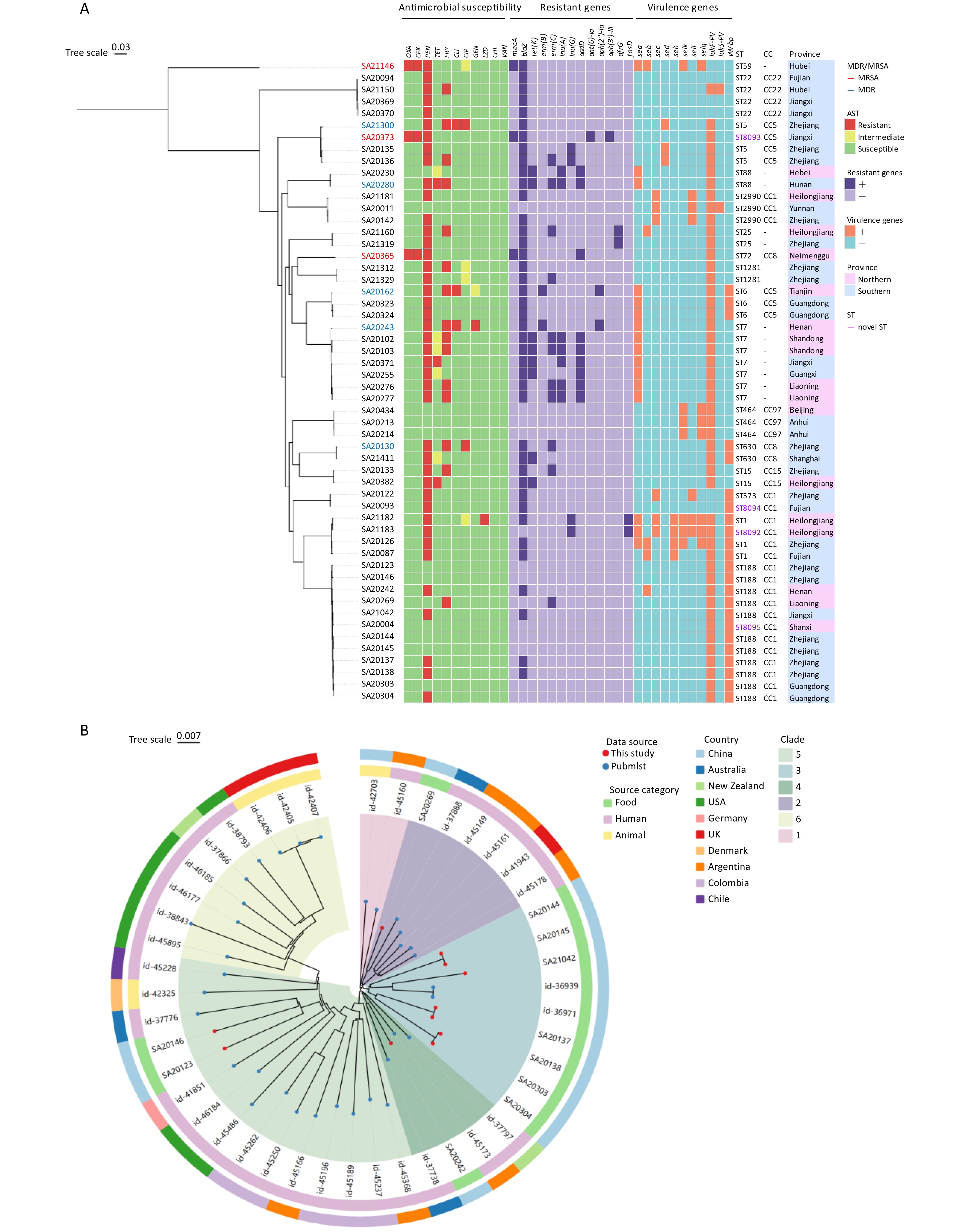

Figure 1. (A) Resistant profiles, resistant genes and virulence factors, genetic relationships of 54 S. aureus isolates, established with phylogenetic analysis. The strain number marked in red and blue indicates the strain as MRSA and MDR, separately. The first 11 columns (red, yellow, green) represent resistance, intermediate, and susceptibility to the corresponding 11 antibiotics, respectively; columns 12-24 indicate the presence (dark purple) or absence (light purple) of resistance genes; columns 25-35 show the carriage of virulence genes, with orange indicating positive and sky blue indicating negative; the four STs in violet were the four novel STs identified in this study; in the province column, blue denotes samples from northern provinces, while magenta indicates samples from southern provinces. (B) Maximum-likelihood SNP phylogenetic tree of ST188. Forty-five S. aureus isolates (11 from this study, 34 download from pubmlst) were used for phylogenetic reconstruction a circle tree. Based on evolutionary distances, the strains are divided into 6 clades, each marked with a fan-shaped area of a different color; The inner ring represents the source category of the strains, and the outer ring represents the countries where the strains were isolated.

The majority of S. aureus isolates (79.6%, 43/54) harbored at least one antimicrobial resistance gene, supporting the results of the phenotypic tests (Figure 1A). The mecA gene, which is responsible for methicillin resistance, was detected in all three methicillin-resistant isolates. The blaZ gene, responsible for penicillin resistance, was the most prevalent (41/45, 75.9%) resistance gene, with a PG concordance of 94.4% (51/54). Eight tet(K)-positive isolates exhibited either resistance (n = 3) or intermediate resistance (n = 5) to tetracycline, with a PG concordance of 90.7% (49/54). The erm(B) and erm(C) genes conferred erythromycin resistance with a PG concordance of 92.6% (50/54). Most erythromycin- and lincomycin-resistant strains carried macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance markers and other related antibiotic resistance genes, including erm(B), erm(C), lnu(A) and lnu(G). Two of the three clindamycin-resistant isolates harbored erm(B). The genes aadD, aph(3')-III and aph(2'')-Ia confer resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics (amikacin and tobramycin), and aph(2'')-Ia mediates gentamicin resistance. The two aph(2")-Ia-positive isolates showed either resistance or intermediate to the aminoglycoside antibiotic gentamicin, yielding a PG concordance of 98.1% (53/54) for gentamicin. Discordance between resistant phenotypes and genotypes was observed in a minority of isolates in this study, which may stem from multiple factors including gene structure, regulatory mechanisms, environmental conditions, and technical limitations, reflecting the principle that “the presence of a gene does not equate to its functional expression.” Specifically, the resistance phenotype to a particular antibiotic may be collectively shaped by multiple genes or resistance mechanisms, potentially involving undiscovered novel genes or new resistance mechanisms. Additionally, resistance genes may harbor mutations or be regulated and repressed at the transcriptional or translational level. Furthermore, the threshold settings in bioinformatics analysis could also lead to the missed detection of certain functional gene variants.

According to the VFDB, eight SE or SEl genes were detected in the isolates. Among the 54 studied isolates, 53.7% (29/54) of the study isolates carried at least one enterotoxin gene. The most predominant one was sea, with the highest carriage rate of 29.6% (16/54) , followed by selk (13.0%, 7/54), selq (13.0%, 7/54), sec (11.1%, 6/54), sell (11.1%, 6/54), seh (7.4%, 4/54), seb (9.3%, 5/54), and sed (5.6%, 3/54) (Figure 1A). The prevalence rate in sea was higher than previous studies, wherein the sea was reported to be present in 24.6% of China[8]. Among many types of SE, SEA is known to be the top contributor (69.7%–86.5%) to SFP in USA and China[9,10]. The high prevalence of enterotoxin genes, particularly sea, poses a significant risk for intoxication. Therefore, once sushi is contaminated with S. aureus, there is a high probability that the isolates will proliferate and produce enterotoxins under improper storage conditions, which in turn may increase the risk of food poisoning for consumers.

Nine enterotoxin gene profiles were identified for these isolates (Table 2). Notably, two isolates (3.7%) carried six enterotoxin genes simultaneously (sea-sec-seh-selk-sell-selq), representing the most complex profile observed. A consistent co-occurrence pattern was observed for selk and selq genes. This is likely because both genes are localized together on S. aureus prophages or pathogenicity islands[2].

No. Enterotoxin gene profiles ST Number of enterotoxin genes Number of isolates Prevalence rate (%) 1 sea-sec-seh-selk-sell-selq ST1, ST8092 6 2 3.7 2 sea-seb-seh-selk-selq ST1 5 1 1.9 3 sea-seb-selk-selq ST59 4 1 1.9 4 seb-seh ST1 2 1 1.9 5 sec-sell ST2990, ST573 2 4 7.4 6 selk-selq ST464 2 3 5.6 7 sea ST7, ST6, ST88 1 12 22.2 8 seb ST25, ST188 1 2 3.7 9 sed ST5 1 3 5.6 10 - ST188, ST22, ST1281, ST15, ST630, ST72,

ST25, ST8093, ST8094, ST80950 25 46.3 Table 2. Staphylococcal enterotoxin gene profiles of S. aureus isolates

Twenty distinct STs were identified, including four novel STs (ST8092, ST8093, ST8094, and ST8095), which are highlighted in violet in Figure 1A. Compared to ST1, ST8092 harbored a novel allele (1063) at the yqiL locus resulting from an SNP, whereas ST8094 carried a novel pta allele (968) with two SNPs. ST8093, when compared to ST5, possessed a novel pta allele (967), also featuring two SNPs. The novel ST8095 exhibited a unique allelic profile (3-1-1-8-1-41-1) that differed from ST188 exclusively at the tpi locus (allele 41). Discovery of novel sequence types (STs) in pathogenic bacteria has epidemiological significance and value. This may advance the understanding of genetic diversity, evolutionary mechanisms, and adaptive strategies of pathogenic bacteria, while improving the accuracy of outbreak source tracing and facilitating the formulation of targeted epidemiological surveillance and public health control strategies.

Among the 20 STs, ST188 emerged as the predominant ST (20.4%, 11/54), followed by ST7 (13.0%, 7/54) and ST22 (7.4%, 4/54). Isolates of ST1, ST2990, ST464, ST5, ST6 each accounted for 5.6% (3/54), followed by isolates of ST1281, ST15, ST25, ST630, and ST88, each accounting for 3.7% (2/54), and the remaining isolates of ST573, ST59, ST72, ST8092, ST8093, ST8094, ST8095, each accounting for 1.9% (1/54). The most common clonal complex (CC) was CC1 that included ST1, ST188, ST2990, ST573, ST8092, ST8094, and ST8095, which was detected in 38.9% (21/54) of isolates. These three MRSA isolates belonged to ST59, ST72, and ST8093, respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed a strong concordance between phylogenetic relationships and ST classification. ST59 and ST22 showed considerable evolutionary divergence from other STs. Distribution of virulence factors was significantly associated with specific STs. ST1 strains were characterized as enterotoxin-rich clones, with all isolates carrying five or more enterotoxin genes belonging exclusively to ST1. Two isolates (3.7%, 2/54) harboring both lukF-PV and lukS-PV genes, encoding the two subunits of PVL, were identified as ST22 and ST2990. PVL, a pore-forming protein, is an important virulence factor that causes a range of pathologies collectively known as PVL-SA disease, through its cytolytic action on the cell membranes of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Accordingly, PVL-positive isolates can lead to more severe and invasive presentations such as necrotizing hemorrhagic pneumonia, necrotizing fasciitis, and purpura fulminans. Furthermore, the vWbp gene was detected in twenty-three (42.6%, 23/54) isolates, predominantly in ST188 and related CC1 members.

As the predominant ST among S. aureus isolates from sushi products, ST188 exhibited distinct genomic and phenotypic characteristics. The 11 ST188 isolates exhibited a significantly lower antimicrobial resistance rates (45.4%, 5/11) compared to the overall cohort (79.6%, 43/54). Notably, all five ST188 strains demonstrated single-drug resistance and were resistant only to penicillin or erythromycin. Virulence gene analysis revealed that these ST188 isolates rarely harbored enterotoxin genes, with only one isolate carrying seb (9.1%, 1/11), but showed 100% prevalence of the vWbp gene.

To investigate the genomic characteristics of the ST188 isolates, we analyzed 11 ST188 isolates from this study, along with 34 global ST188 reference genomes retrieved from PubMLST (accession numbers and detailed information provided in Supplementary Table S1), and constructed a core-genome SNP phylogenetic tree. Based on the results of the analysis with the VFDB, the vast majority (97.7%, 42/45) of ST188 isolates carried the vWbp gene. Among the enterotoxin genes, only seb was detected, with a carrying rate of 17.8% (8/45). The phylogeny of S. aureus ST188 showed 6 distinct clades . The majority of food-associated isolates (69.2%, 9/13) were clustered within clade 3, whereas the remaining four food-associated isolates were dispersed across other three clades (2, 4, 5) and co-clustered with the human-associated strains. Geographic mapping of all ST188 isolates revealed no significant association between genetic clustering and the source country (Figure 1B). ST188 is commonly reported to have been isolated from humans and is associated with a variety of clinical infections, including bloodstream infections and bacteremia. Many studies have suggested that the virulence of ST188 is related to its adhesion and colonization abilities, but the key genes involved are not well understood. In our study, we found that compared to other ST types, the vWbp gene had an extremely high carriage rate in ST188. Gene vWbp is the coding gene of a von Willebrand factor-binding protein, which is reported to be a key factor for anchoring S. aureus to the vessel wall and a determinant of the joint-invading capacity of S. aureus. This may be related to the high prevalence of ST188 in bloodstream infections and bacteremia. Therefore, despite the lack of antimicrobial resistance and enterotoxin genes, the isolation of ST188 from sushi should be considered an important food safety risk, warranting further investigation through in vitro and in vivo pathogenicity studies.

In summary, this study presents the first comprehensive genomic characterization of S. aureus contamination in commercially available sushi products in China. The low tetracycline resistance and specific STs of S. aureus in sushi suggest that the potential primary source of S. aureus contamination in sushi may not be livestock-associated ingredients but human food handlers. However, this hypothesis requires verification through comparative studies involving S. aureus isolates from food handlers and processing environments. Owing to the high carriage rate of enterotoxin genes, especially sea, S. aureus contamination of sushi poses a considerable risk of SFP. Phenotype and genotype analyses showed that most of these isolates were linked to human infections and may have pathogenic potential. Enhanced monitoring of these high-risk strains during sushi production is imperative to facilitate the development of effective food safety strategies for preventing potential staphylococcal foodborne illnesses. Given the vast geographical territory and large population of China, the sample size in this study was relatively limited and may not be fully representative of the national situation. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution, and larger and more systematic studies are warranted to validate these trends across the country.

HTML

Competing Interests The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Data Sharing The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Supplementary materials are available in www.besjournal.com.

Reference

Quick Links

Quick Links

DownLoad:

DownLoad: