-

There has been an increase in the prevalence of childhood obesity across the world within less than one generation, with a more rapid increase in middle-income and low-income countries[1]. In China, it has been reported that the prevalence of childhood obesity among boys and girls aged 7–18 years increased substantially from 1985 to 2014, and was by 9.1% in 2014[2]. Childhood obesity increases the risks for adulthood obesity and serious health conditions such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, sleep-disordered breathing, and infertility[3-5], and it has emerged as one of the most serious public health challenges.

Obesity increases the risk for not only several diseases but also severe psychological consequences, one among which is body dissatisfaction, i.e., the discrepancy in perception between the real and an idealized body shape. Due to the widespread increase in the prevalence of childhood obesity, the problem of body dissatisfaction has become increasingly common among children, particularly girls. One study reported that 50% of girls aged 7–11 years expected to be more slender than their current perceived body[6]. In addition, the prevalence of body dissatisfaction was found to be higher among obese children than among children with normal weight. Mulasi-Pokhriyal et al. observed that approximately 70% of obese children in their study desired to lose weight[7]. Another research demonstrated that body dissatisfaction was a risk factor for restrictive diets, compensatory behaviors, binge eating, and eating disorders[8].

It has been well established that adverse dietary factors are important risk factors for obesity, including the consumption of excess dietary fat and refined carbohydrates and sugared soft drinks and unhealthy dietary behaviors[9]. Stankiewicz et al. reported that 91.0% of children believed that vegetables and fruits were helpful in maintaining their health[10]. Changes in meal patterns may affect dietary intakes and thus provide potential behavioral targets for intervention programs to prevent the development of obesity and specific chronic diseases[11].

Correlations may exist among obesity, body dissatisfaction, and CWL. It is not known whether body dissatisfaction is the mediating factor between obesity and DBCWL. Addressing this issue could provide an important opinion for developing more effective measures for weight loss. Therefore, this study was conducted to explore the mediating effects of body dissatisfaction in correlation between obesity and DBCWL.

-

Using the stratified cluster sampling method, a total of 720 Chinese children and adolescents studying from Grades 2 to 5 in elementary schools and from Grades 1 to 2 in middle schools in Beijing city were selected for this study. The effective sample size was 680 comprising 333 boys and 347 girls. Informed consent was signed before conducting the investigation.

-

Body height, weight, and waistline of the study participants were measured according to the requirements of the Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH) research rules[12]. The participants were required to wear only light clothes and stand straight barefoot for conducting the measurements. All measurements were performed by professional technicians who had passed a training course for conducting anthropometric measurements. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg)/square of body height (m2). Overweight/obesity was defined according to the BMI reference of working group on obesity in China (WGOC)[13]. Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was calculated as waist (cm)/height (cm), and abdominal obesity was defined as WHtR ≥0.46[14].

-

Dietary behaviors and DBCWL of the study participants were evaluated in this study. The students’ dietary behaviors comprised six items of perception, including consumption of vegetables or fruits, dried food, Western fast food, high-calorie snacks, sugared beverages, and a breakfast every day. Students were asked to answer their perception of these factors by responding to some questions such as ‘Do you think eating less vegetable or fruit is right?’ The answer included Yes or No. DBCWL were evaluated by the following one question: ‘Have you lost your body weight by changing your dietary behaviors in the recent 2 weeks?’ The answer included Yes or No.

The Ma body figural shape was used to evaluate the body image attitude of the participants. The Ma body figural shape ranging from very thin to very fat is composed of seven figure drawings for each gender, which are respectively scored as ‘1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7’. Participants were asked to select one drawing that fits best with each of the following statements: (1) which one do you think is the right one for you now? This aspect was assessed to survey the self-body shape perception. (2) Which one would you most want to look like? This parameter was assessed to survey the expected shape perception. The difference in scores between the self-body shape perception and the expected shape perception was used to calculate body dissatisfaction rating. If the body dissatisfaction rating is equal to 0, it indicates body satisfaction; otherwise, it is considered as body dissatisfaction[15].

-

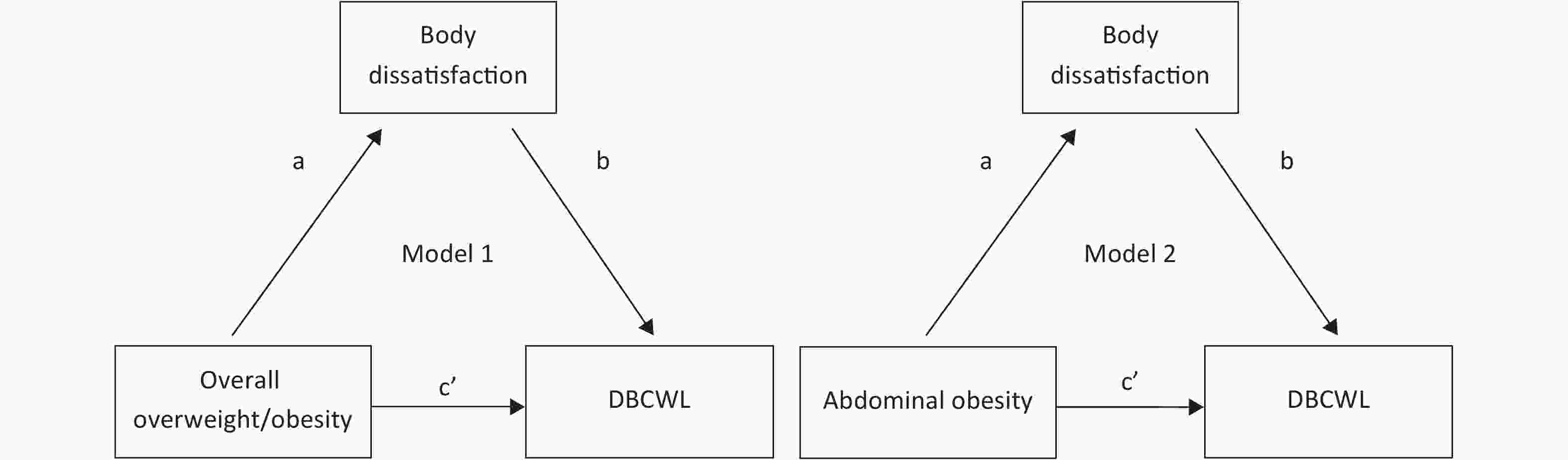

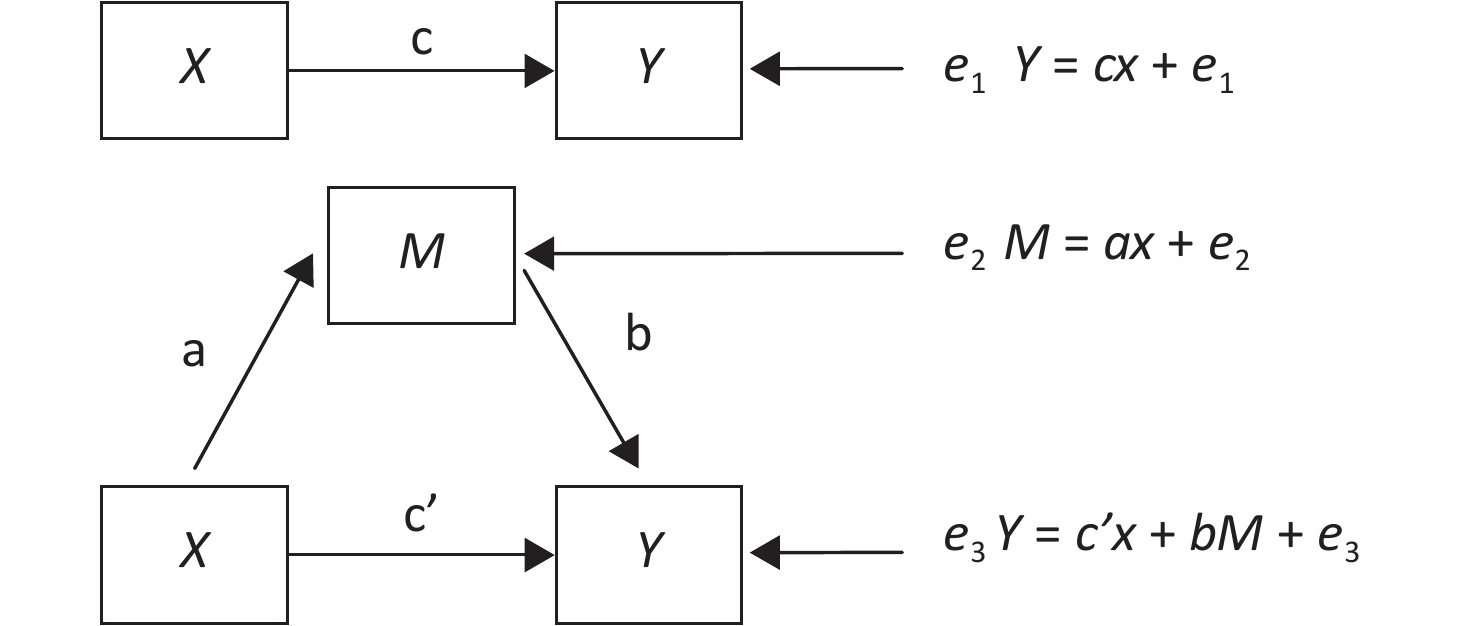

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS23.0 software. The enumerated data were represented by frequency, and the difference between groups were compared using a chi-square test. Based on the theory of mediating effects proposed by Baron and Kenny[16], body dissatisfaction was considered as a mediator factor (M), obesity (X) was considered as an independent variable, and DBCWL were considered as a dependent variable (Y) for mediating the effect analysis. The total effect (c) of factor X on factor Y can be decomposed into direct effect (c′) and mediating effect (ab). 'a' was the effect of factor X on factor M, and 'b' was the effect of factor M on factor Y after adjusting for factor X (Figure 1). Logistic regression models were used to analyze the mediating effects, which were subsequently evaluated using the Sobel method.

-

Among the 680 students, 36.6% were overweight/obesity, 40.4% had abdominal obesity, 70.1% had body dissatisfaction, 72.4% had DBCWL, and > 80% had correct perceptions about dietary behaviors. The prevalence of overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity was significantly higher in males than in females (P < 0.001). However, the rate of correct perception about the consumption of dried foods and Western fast food was significantly lower in males than in females (P < 0.05). The rates of DBCWL and correct perception about the consumption of sugared beverages, breakfast, dried foods, Western fast food, and high-calorie snacks were significantly higher in students aged 7– years than in students aged 11– years (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1. The rate of DBCWL, body dissatisfaction, obesity and dietary behavior perception by gender and ages (%)

Variables Total

(n = 680)Gender x2 P Ages (years) x2 P Female

(n = 333)Male

(n = 347)7−

(n = 337)11−

(n = 343)Overweight/obesity 15.77 < 0.001 1.46 0.226 No 63.4 70.9 56.2 61.1 65.6 Yes 36.6 29.1 43.8 38.9 34.4 Abdominal obesity 10.44 0.001 0.01 0.911 No 59.6 65.8 53.6 59.3 59.8 Yes 40.4 34.2 46.4 40.7 40.2 Body dissatisfaction 0.19 0.662 0.02 0.900 No 22.9 22.2 23.6 23.1 22.7 Yes 70.1 77.8 76.4 76.9 77.3 DBCWL 0.13 0.723 6.77 0.009 No 27.6 27.0 28.2 23.1 32.1 Yes 72.4 73.0 71.8 76.9 67.9 More eating vegetable or fruit 0.13 0.723 2.90 0.088 No 17.6 17.1 18.2 15.1 20.1 Yes 82.4 82.9 81.8 84.9 79.9 Less drinking sugared beverage 0.61 0.436 21.75 < 0.001 No 14.0 12.9 15.0 7.7 20.1 Yes 86.0 87.1 85.0 92.3 79.9 Having a breakfast per day 0.09 0.764 5.21 0.022 No 8.4 8.7 8.1 5.9 10.8 Yes 91.6 91.3 91.9 94.1 89.2 Less eating dried food 7.93 0.005 15.79 < 0.001 No 17.1 12.9 21.0 11.3 22.7 Yes 82.9 87.1 79.0 88.7 77.3 Less eating western fast food 11.21 0.001 7.24 0.007 No 17.9 12.9 22.8 13.9 21.9 Yes 82.1 87.1 77.2 86.1 78.1 Less eating high-calorie snacks 1.43 0.231 17.71 < 0.001 No 16.8 15.0 18.4 10.7 22.7 Yes 83.2 85.0 81.6 89.3 77.3 As shown in Table 2, after adjusting for gender and age, overweight/obesity, abdominal obesity, and body dissatisfaction significantly increased the risk for DBCWL (OR = 2.57, 2.77, and 1.95, respectively). Furthermore, overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity significantly increased the risk for body dissatisfaction (OR = 6.00 and 4.70, respectively). However, no significant correlation was found between the perception of dietary behaviors and DBCWL and between DBCWL and body dissatisfaction. There was also no significant correlation among overweight/obesity, abdominal obesity, and dietary behavior perception (Table 3).

Table 2. The influence of obesity and dietary behaviors perception on DBCWL and body dissatisfaction

Variables N DBCWL Body dissatisfaction % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) Overweight/obesity No 431 66.1 Reference 68.2 Reference Yes 249 83.1 2.57 (1.73−3.80) 92.4 6.00 (3.58−10.05) Abdominal obesity No 405 64.9 Reference 67.9 Reference Yes 275 83.3 2.77 (1.89−4.05) 90.5 4.70 (2.97−7.43) Body dissatisfaction No 156 61.5 Reference Yes 524 75.6 1.95 (1.33−2.86) Less eating vegetable or fruit Yes 120 74.2 Reference No 560 72.0 0.86 (0.55−1.35) More drinking sugared beverage Yes 95 72.6 Reference No 585 72.3 0.87 (0.53−1.43) Having a breakfast per day No 57 66.7 Reference Yes 623 72.9 1.26 (0.70−2.26) Less eating dried food No 116 70.7 Reference Yes 564 72.7 1.01 (0.64−1.58) Often eating western fast food Yes 122 66.4 Reference No 558 73.7 1.34 (0.87−2.05) More eating high-calorie snacks Yes 114 66.7 Reference No 566 73.5 1.27 (0.82−1.97) Table 3. The influence of obesity and body dissatisfaction on dietary behaviors perception

Variables N Less eating vegetable or fruit More drinking sugared beverage Having a breakfast per day % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) Obesity No 431 84.0 Reference 84.9 Reference 91.2 Reference Yes 249 79.5 0.73 (0.48−1.09) 88.0 1.27 (0.79−2.05) 92.4 1.12 (0.62−2.00) Abdominal obesity No 405 84.9 Reference 85.4 Reference 91.6 Reference Yes 275 78.5 0.65 (0.43−0.97) 86.9 1.15 (0.73−1.82) 91.6 0.99 (0.56−1.73) Body dissatisfaction No 156 83.3 88.5 94.2 Yes 524 82.1 0.92 (0.57−1.48) 85.3 0.75 (0.43−1.31) 90.8 0.61 (0.29−1.28) Variables N Less eating dried food Often eating western fast food More eating high-calorie snacks % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) Obesity No 431 82.4 Reference 83.3 Reference 83.1 Reference Yes 249 83.9 1.18 (0.77−1.82) 79.9 0.86 (0.57−1.29) 83.5 1.03 (0.67−1.58) Abdominal obesity No 405 83.0 Reference 82.7 Reference 83.2 Reference Yes 275 82.9 1.06 (0.70−1.61) 81.1 0.97 (0.64−1.45) 83.3 1.03 (0.68−1.56) Body dissatisfaction No 156 84.0 Reference 80.8 Reference 81.4 Reference Yes 524 82.6 0.89 (0.54−1.46) 82.4 1.10 (0.69−1.75) 83.8 1.18 (0.74−1.90) The above-described results revealed that obesity, body dissatisfaction, and DBCWL were significantly correlated. The mediating effect models were used to determine the mediating effect of body dissatisfaction in correlation between obesity and DBCWL after adjusting for gender and age using logistic regressions (Figure 2). The results of this analysis demonstrated significant mediating effects of body dissatisfaction in correlation between overweight/obesity and DBCWL and between abdominal obesity and DBCWL, with the OR values being 2.20 and 1.92, respectively (P < 0.05) (Table 4). The proportions of mediating effects among the total effects were 48.89% and 46.60% for overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity, respectively.

Table 4. The mediating effect of body dissatisfaction in correlation between obesity and DBCWL

Model Effect β Se Wald P OR (95% CI) Model 1 a 1.79 0.26 46.25 < 0.001 6.00 (3.58−10.05) b 0.44 0.20 4.63 0.031 1.55 (1.04−2.30) c' 0.83 0.21 16.04 < 0.001 2.30 (1.53−3.45) ab 0.79 0.38 4.32 0.038 2.20 (1.05−4.64) Model 2 a 1.55 0.23 43.68 < 0.001 4.70 (2.97−7.43) b 0.42 0.20 4.30 0.038 1.52 (1.02−2.27) c' 0.92 0.20 21.03 < 0.001 2.51 (1.69−3.72) ab 0.65 0.32 4.14 0.042 1.92 (1.02−3.59) Note. All analysis adjusted for gender and ages. a, the effect of overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity on body dissatisfaction; b, the effect of body dissatisfaction on DBCWL after controlling overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity; c’, the direct effect of overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity on DBCWL controlling body dissatisfaction; ab, the mediating effect of body dissatisfaction on correlation between overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity and DBCWL. -

In this study, there were 36.6% of children with overweight/obesity and 40.4% with abdominal obesity, which were higher than those among children from the general population in China. However, these proportions were similar to those among children from developed countries. In China, the prevalence rates of overweight and obesity were found to be 13.3% and 6.9% among boys and 8.9% and 1.8% among girls, respectively, according to the 2010 Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH) data[17]. The prevalence of overweight or obesity among children in areas with a higher economic level was found to be higher than that among children in areas with a lower economic level[18]. The children in this study were selected from elementary and middle schools in Beijing city, which might be the reason for the higher prevalence of overweight or obesity than that of national data (2010). Zuraikat et al. reported a prevalence of 36% for both obesity and overweight among school-age children in Pennsylvania[19]. Similarly, Freitas et al. found childhood overweight or obesity, as among 31.6% of children in Portugal[20]. In addition, results of the present study demonstrated that the prevalence of overweight/obesity was significantly higher in boys than in girls, Which is consistent with the finding reported by Song et al., who also observed a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity in boys than in girls[21]. However, results from developed countries indicate a higher prevalence of obesity in girls than in boys[22]. The higher prevalence of obesity in boys than in girls observed in this study and previous research may be due to the unhealthy dietary behaviors that were more common among boys than among girls. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the rate of correct perception about the consumption of dried foods and Western fast food was significantly lower in males than in females.

In this study, 70.1% of children and adolescents had body dissatisfaction, which was similar to previous results from developing countries, but slightly lower than that from developed countries. Li et al.[23] reported that 69.9% of Chinese children were dissatisfied with their body size. Furthermore, Mulasi-Pokhriyal et al. reported that 79% of girls and 69% of boys aged 9–18 years in the United States were discontented with their physical appearance[7]. Studies have also indicated that girls were more dissatisfied with their body than boys[24, 25]. However, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of body dissatisfaction between boys and girls in the present study, which may be related to the higher rates of obesity among boys than among girls. This study also showed that overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity significantly increased the risk for body dissatisfaction (OR = 6.00 and 4.70, respectively, after adjusting for gender and age). Similarly, Ferrari et al. reported that both BMI and BF% were significantly associated with body dissatisfaction (OR = 5.25 and 2.42, respectively)[26]. Serious body dissatisfaction was especially found among obese girls[27].

In the present study, > 80% of the students were found to have correct perceptions about eating behaviors. This finding was consistent with that of Triches et al. who reported that 90.8% of children correctly responded to the questions concerning foods[28]. Furthermore, the rate of correct perception about the consumption of dried foods and Western fast food was significantly lesser in males than in females in this study, which may be associated with the fact that girls were more concerned about their body than boys and more expected to become thinner[29]. It is well known that improvement of dietary behaviors is an important measure for weight loss. In this study, although 72.4% of children had DBCWL, there was no significant correlation between dietary behavior perception and DBCWL. Therefore, improving the dietary behavior perception was found to be insufficient to improve DBCWL, which was consistent with the results of previous studies[28, 30-34].

Results of this study revealed that overweight/obesity, abdominal obesity, and body dissatisfaction significantly increased the risk for DBCWL (OR = 2.57, 2.77, and 1.95 after adjusting for gender and age, respectively). Moreover, the mediating effect models among obesity, body dissatisfaction and DBCWL was conducted. The proportions of 48.89% and 46.60% of the mediating effects of body dissatisfaction in association between DBCWL and overweight/obesity and between DBCWL and abdominal obesity indicate that body dissatisfaction plays about half the role in DBCWL. Body dissatisfaction should be considered as an important psychological problem while analyzing the aspects of dietary behavior improvement for weight loss to provide correct guidance to children and adolescents. Moreover, it is important to distinguish obese children with and without body dissatisfaction to implement effective measures for preventing obesity. In addition, we must focus more on body dissatisfaction among children with normal weight and DBCWL. These children may display restrictive dietary behaviors to realize their healthy growth and development.

There were several limitations in the present cross-sectional study. First, it was not clear whether the correct dietary behaviors occurred before or after being obese, which was a limitation to interpret an association between obesity and dietary behavior perception. Second, the causal relationship among obesity, body dissatisfaction, and DBCWL could not be explained. Finally, the DBCWL was unclearly defined as healthy or unhealthy dietary behaviors changes for weight loss.

-

This study demonstrated that body dissatisfaction might exert mediating effects between obesity and DBCWL in Chinese children, which indicated that guiding children to correctly recognize their body might be more conducive than promoting obese children toward weight loss through dietary behavior changes.

-

The authors would like to thank the students who participated in the current study.

-

All authors have no conflict of interest.

-

GAO HQ and WANG BX collected and analyzed the data, prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and had equivalent contribution. SUN LL, LI T, and WU L analyzed the data. FU LG and MA J conceived and designed the research and revised the manuscript.

doi: 10.3967/bes2019.083

The Mediating Effect of Body Dissatisfaction in Association between Obesity and Dietary Behavior Changes for Weight Loss in Chinese Children

-

Abstract:

Objective The aim of this study was to analyze the mediating effect of body dissatisfaction in correlation between obesity and dietary behavior changes for weight loss (DBCWL). Methods A total of 680 primary and middle school students were included in this study. Their body height, weight, and waistline were effectively measured, and they were also evaluated to assess their body dissatisfaction, perception of dietary behaviors, and DBCWL. The correlation among these factors was analyzed using mediating effect models. Results The prevalence of overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity was significantly higher in males than in females (P < 0.05). Overweight/obesity, abdominal obesity, and body dissatisfaction significantly increased the risk for DBCWL (OR = 2.57, 2.77, and 1.95, respectively). Overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity significantly increased the risk for body dissatisfaction (OR = 6.00 and 4.70, respectively). Significant mediating effects of body dissatisfaction were observed in correlation between overweight/obesity and DBCWL and between abdominal obesity and DBCWL (OR = 2.20 and 1.92, respectively; P < 0.05), and the proportions of mediating effects among the total effects were 48.89% and 46.60%, respectively. Conclusion Body dissatisfaction might play an important mediating effect in association between DBCWL and obesity, which indicates that guiding children to correctly recognize their body might be more conducive than promoting obese children toward weight loss through dietary behavior changes. -

Table 1. The rate of DBCWL, body dissatisfaction, obesity and dietary behavior perception by gender and ages (%)

Variables Total

(n = 680)Gender x2 P Ages (years) x2 P Female

(n = 333)Male

(n = 347)7−

(n = 337)11−

(n = 343)Overweight/obesity 15.77 < 0.001 1.46 0.226 No 63.4 70.9 56.2 61.1 65.6 Yes 36.6 29.1 43.8 38.9 34.4 Abdominal obesity 10.44 0.001 0.01 0.911 No 59.6 65.8 53.6 59.3 59.8 Yes 40.4 34.2 46.4 40.7 40.2 Body dissatisfaction 0.19 0.662 0.02 0.900 No 22.9 22.2 23.6 23.1 22.7 Yes 70.1 77.8 76.4 76.9 77.3 DBCWL 0.13 0.723 6.77 0.009 No 27.6 27.0 28.2 23.1 32.1 Yes 72.4 73.0 71.8 76.9 67.9 More eating vegetable or fruit 0.13 0.723 2.90 0.088 No 17.6 17.1 18.2 15.1 20.1 Yes 82.4 82.9 81.8 84.9 79.9 Less drinking sugared beverage 0.61 0.436 21.75 < 0.001 No 14.0 12.9 15.0 7.7 20.1 Yes 86.0 87.1 85.0 92.3 79.9 Having a breakfast per day 0.09 0.764 5.21 0.022 No 8.4 8.7 8.1 5.9 10.8 Yes 91.6 91.3 91.9 94.1 89.2 Less eating dried food 7.93 0.005 15.79 < 0.001 No 17.1 12.9 21.0 11.3 22.7 Yes 82.9 87.1 79.0 88.7 77.3 Less eating western fast food 11.21 0.001 7.24 0.007 No 17.9 12.9 22.8 13.9 21.9 Yes 82.1 87.1 77.2 86.1 78.1 Less eating high-calorie snacks 1.43 0.231 17.71 < 0.001 No 16.8 15.0 18.4 10.7 22.7 Yes 83.2 85.0 81.6 89.3 77.3 Table 2. The influence of obesity and dietary behaviors perception on DBCWL and body dissatisfaction

Variables N DBCWL Body dissatisfaction % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) Overweight/obesity No 431 66.1 Reference 68.2 Reference Yes 249 83.1 2.57 (1.73−3.80) 92.4 6.00 (3.58−10.05) Abdominal obesity No 405 64.9 Reference 67.9 Reference Yes 275 83.3 2.77 (1.89−4.05) 90.5 4.70 (2.97−7.43) Body dissatisfaction No 156 61.5 Reference Yes 524 75.6 1.95 (1.33−2.86) Less eating vegetable or fruit Yes 120 74.2 Reference No 560 72.0 0.86 (0.55−1.35) More drinking sugared beverage Yes 95 72.6 Reference No 585 72.3 0.87 (0.53−1.43) Having a breakfast per day No 57 66.7 Reference Yes 623 72.9 1.26 (0.70−2.26) Less eating dried food No 116 70.7 Reference Yes 564 72.7 1.01 (0.64−1.58) Often eating western fast food Yes 122 66.4 Reference No 558 73.7 1.34 (0.87−2.05) More eating high-calorie snacks Yes 114 66.7 Reference No 566 73.5 1.27 (0.82−1.97) Table 3. The influence of obesity and body dissatisfaction on dietary behaviors perception

Variables N Less eating vegetable or fruit More drinking sugared beverage Having a breakfast per day % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) Obesity No 431 84.0 Reference 84.9 Reference 91.2 Reference Yes 249 79.5 0.73 (0.48−1.09) 88.0 1.27 (0.79−2.05) 92.4 1.12 (0.62−2.00) Abdominal obesity No 405 84.9 Reference 85.4 Reference 91.6 Reference Yes 275 78.5 0.65 (0.43−0.97) 86.9 1.15 (0.73−1.82) 91.6 0.99 (0.56−1.73) Body dissatisfaction No 156 83.3 88.5 94.2 Yes 524 82.1 0.92 (0.57−1.48) 85.3 0.75 (0.43−1.31) 90.8 0.61 (0.29−1.28) Variables N Less eating dried food Often eating western fast food More eating high-calorie snacks % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) % OR (95% CI) Obesity No 431 82.4 Reference 83.3 Reference 83.1 Reference Yes 249 83.9 1.18 (0.77−1.82) 79.9 0.86 (0.57−1.29) 83.5 1.03 (0.67−1.58) Abdominal obesity No 405 83.0 Reference 82.7 Reference 83.2 Reference Yes 275 82.9 1.06 (0.70−1.61) 81.1 0.97 (0.64−1.45) 83.3 1.03 (0.68−1.56) Body dissatisfaction No 156 84.0 Reference 80.8 Reference 81.4 Reference Yes 524 82.6 0.89 (0.54−1.46) 82.4 1.10 (0.69−1.75) 83.8 1.18 (0.74−1.90) Table 4. The mediating effect of body dissatisfaction in correlation between obesity and DBCWL

Model Effect β Se Wald P OR (95% CI) Model 1 a 1.79 0.26 46.25 < 0.001 6.00 (3.58−10.05) b 0.44 0.20 4.63 0.031 1.55 (1.04−2.30) c' 0.83 0.21 16.04 < 0.001 2.30 (1.53−3.45) ab 0.79 0.38 4.32 0.038 2.20 (1.05−4.64) Model 2 a 1.55 0.23 43.68 < 0.001 4.70 (2.97−7.43) b 0.42 0.20 4.30 0.038 1.52 (1.02−2.27) c' 0.92 0.20 21.03 < 0.001 2.51 (1.69−3.72) ab 0.65 0.32 4.14 0.042 1.92 (1.02−3.59) Note. All analysis adjusted for gender and ages. a, the effect of overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity on body dissatisfaction; b, the effect of body dissatisfaction on DBCWL after controlling overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity; c’, the direct effect of overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity on DBCWL controlling body dissatisfaction; ab, the mediating effect of body dissatisfaction on correlation between overweight/obesity or abdominal obesity and DBCWL. -

[1] Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, et al. Child and adolescent obesity: part of a bigger Picture. Lancet, 2015; 385, 2510−20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61746-3 [2] Dong YH, Zou ZY, Hu PJ, et al. Secular trends of ascariasis infestation and nutritional status bin Chinese children from 2000 to 2014: Evidence from 4 successive national surveys. Open Forum Infect Dis, 2019; 6, ofz193. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz193 [3] Daniels SR, Jacobson MS, McCrindle BW, et al. American Heart association childhood obesity research summit: executive summary. Circulation, 2009; 119, 2114−23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192215 [4] Xue HM, Liu Y, Duan RN, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in China and its related influential factors. Chin J School Health, 2014; 8, 1258−62. (In Chinese) [5] Ma J, Cai CH, Wang HJ, et al. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among Chinese students in 1985-2000. Chin J Prev Med, 2012; 46, 776−80. (In Chinese) [6] Evans EH, Tovée MJ, Boothroyd LG. Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes in 7- to 11-year-old girls: testing a sociocultural model. Body Image, 2013; 10, 8−15. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.10.001 [7] Mulasi-Pokhriyal U, Smith C. Assessing body image issues and body satisfaction/dissatisfaction among Hmong American children 9-18 years of age using mixed methodology. Body Image, 2010; 7, 341−8. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.08.002 [8] Elke GS, Aiko M, Johanna K, et al. Body dissatisfaction in normal weight children–sports activities and motives for engaging in sports. Eur J Sport Sci, 2018; 18, 1−9. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2016.1249524 [9] Kyungho H, Sangwon C, Haeng-Shin L, et al. Association of dietary sugars and sugar-sweetened beverage intake with obesity in Korean children and adolescents. Nutrients, 2016; 8, 31. doi: 10.3390/nu8010031 [10] Stankiewicz M, Pieszko M, Sliwinska A, et al. Obesity and diet awareness among Polish children and adolescents in small towns and villages. Cent Eur J Public Health, 2014; 22, 12−6. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3813 [11] Nicklas TA, Morales M, Linares A, et al. Children's meal patterns have changed over a 21-year period: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Am Diet Assoc, 2004; 104, 753−61. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.02.030 [12] Research group of students' Constitution and health in China. Research Report on Chinese students' Constitution and health in 2010. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2012; 371-434. (In Chinese) [13] WHO. Western Pacific Region, international association for the study of obesity. The Asia-Pacific perspective. Redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia, 2000. [14] Meng LH, MI J, Cheng H, et al. Study on the distribution characteristics and appropriate boundary value of waist circumference and waist to height ratio between 3 and 18 years old in Beijing city. Chin J Evidence Based Pediatrics, 2007; 04, 245−52. (In Chinese) [15] Fu LG, Wang HJ, Sun LL, et al. Correlation between parameters on the shape of body and dissatisfaction against it from parents among children and adolescents. Chin J Epidemiol, 2015; 36, 318−22. (In Chinese) [16] Baron RM. Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1986; 51, 1173−82. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [17] Fu LG, Sun LL, Wu SW, et al. The Influence of Secular Trends in Body Height and Weight on the Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity among Chinese Children and Adolescents. Biomed Environ Sci, 2016; 29, 849−57. [18] Wu SQ, Ding YY, Wu FQ, et al. Socio-economic position as an intervention against overweight and obesity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep, 2015; 5, 11354. doi: 10.1038/srep11354 [19] Zuraikat N, Dugan C. Overweight and obesity among children: An evaluation of a walking program. Hosp Top, 2015; 93, 36−43. doi: 10.1080/00185868.2015.1052283 [20] Freitas AI, Moreira C, Santos AC. Time trends in prevalence and incidence rates of childhood overweight and obesity in Portugal: Generation XXI birth cohort. Int J Obes (Lond), 2019; 43, 424−7. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0286-8 [21] Song Y, Wang HJ, Ma J, et al. Secular trends of obesity prevalence in urban Chinese children from 1985 to 2010: gender disparity. PLoS One, 2013; 8, e53069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053069 [22] Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet, 2017; 390, 2627−42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [23] Li Y, Hu X, Ma W, et al. Body image perceptions among Chinese children and adolescents. Body Image, 2005; 2, 91−103. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.04.001 [24] Bearman SK, Martinez E, Stice E, et al. The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. J Youth Adolesc, 2006; 35, 217−29. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9 [25] Storvoll EE, Strandbu A, Wichstrøm L. A cross-sectional study of changes in Norwegian adolescents' body image from 1992 to 2002. Body Image, 2005; 2, 5−18. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.01.001 [26] Ferrari EP, Minatto G, Berria J, et al. Body image dissatisfaction and anthropometric indicators in male children and adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr, 2015; 69, 1140−4. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.252 [27] Weinberger NA, Kersting A, Riedel-Heller SG. Body dissatisfaction in individuals with obesity compared to normal-weight individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Facts, 2016; 9, 424−41. doi: 10.1159/000454837 [28] Triches RM, Giugliani, ER. Obesity, eating habits and nutritional knowledge among school children. Rev Saude Publica, 2005; 39, 541−7. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102005000400004 [29] Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Richardson B, Lewis V, et al. Do women with greater trait body dissatisfaction experience body dissatisfaction states differently? An experience sampling study. Body Image, 2018; 25, 1−8. [30] J Piwoński, A Pytlak. The health behaviour and the level of knowledge on selected problems of heart diseases prophylaxis among Warsaw school-aged children. Pytlak A, 2003. [31] Stark CM, Graham-Kiefer ML, Devine CM, et al. Online course increases nutrition professionals' knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy in using an ecological approach to prevent childhood obesity. J Nutr Educ Behav, 2011; 43, 316−22. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.01.010 [32] Harnack L, Stang J, Story M. Soft drink consumption among US children and adolescents: nutritional consequences. J Am Diet Assoc, 1999; 99, 436−41. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00106-6 [33] Woynarowska B, Małkowska-Szkutnik A, Mazur J, et al. School meals and policy on promoting healthy eating in schools in Poland. Med Wieku Rozwoj, 2011; 15, 232−9. [34] Nicklas TA, Baranowski T, Cullen KW, et al. Eating patterns, dietary quality and obesity. J Am Coll Nutr, 2001; 20, 599−608. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719064 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links