-

Given the dual pressures of population aging and the steady rise in the prevalence of metabolic risk factors, China faces a serious challenge of the continuously increasing burden of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including acute myocardial infarction (AMI), particularly in rural areas[1,2]. Since 2013, patients with AMI living in rural China have experienced persistently higher mortality rates than their urban counterparts[2]. This discrepancy emphasizes the necessity of quality improvement efforts among rural medical systems at the national level. Previously, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) quality in rural China was only studied in surveys that included ideal patients for reperfusion therapy or were conducted in hospitals without percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) capabilities[3-5], both of which may not represent real-world management among all rural patients with STEMI. Alternatively, some province-wide registry studies reported results for a limited number of patients or were restricted to short-term follow-ups[6,7]. The relationship between different reperfusion strategies and the long-term prognosis of patients with STEMI in rural China has not been well investigated in a real-world scenario.

Given that China’s primary public medical system adheres to a traditional vertical administrative model, with provinces, prefectures, and counties arranged in descending order of size and level, county-level hospitals located in small cities adjacent to rural areas are the mainstay of rural medical and health services[8]. Using data from the China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) registry, we investigated the 2-year mortality in patients with STEMI admitted to county-level hospitals according to the reperfusion strategy at the acute stage.

-

The full protocol of the CAMI registry has been previously published[9]. Briefly, 108 hospitals from 31 provinces and municipalities throughout mainland China participated in the registry between January 2013 and September 2014, including 32 county-level hospitals. During this period, the median number of patients with AMI admitted annually in these county-level hospitals was 80, and the median bed number in cardiology units was 47; Seventy-eight percent had a coronary care unit, and 44.0% had a catheterization laboratory. The proportion of capacity of fibrinolysis, PCI, and primary PCI capabilities was 91.4%, 37.1%, and 31.4%, respectively[10].

Patients with a primary diagnosis of STEMI admitted to county-level hospitals within 7 days of the onset of ischemic symptoms were included in the study. The final diagnosis had to meet the third Universal Definition for Myocardial Infarction, including types 1, 2, 3, 4b, and 4c[11]. Types 4a and 5 AMIs were not eligible for the CAMI registry.

-

Data were collected, validated, and submitted through a secure web-based electronic data capture system. The follow-up was performed by trained physicians at each participating site in real-time to ensure data accuracy and reliability. Senior cardiologists were responsible for data quality control, and periodic database checking was performed.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Hospital and each local institution (No. 431). Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients upon admission. Patient information was de-identified before the analysis. This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01874691).

-

The successful clinical reperfusion after fibrinolysis was assessed according to non-invasive markers, including significant relief of chest pain, ST-segment resolution ≥ 50.0%, the occurrence of reperfusion arrhythmia, and early peak value of myocardial necrosis markers[12]. Total ischemic time was defined as the symptom onset-to-balloon time for primary PCI and the symptom onset-to-needle time for fibrinolysis. Prehospital delay was defined as the time from symptom onset to hospital admission. Post-fibrinolysis PCI within 24 h from symptom onset represented routine angiography with subsequent PCI for successful fibrinolysis and rescue PCI for failed fibrinolysis.

The primary clinical outcome was the 2-year all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included death, reinfarction, stroke, and major bleeding during hospitalization. Major bleeding was defined as any fatal or life-threatening bleeding or bleeding associated with a 5-g/dL fall in hemoglobin or intracranial bleeding.

-

The baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of the patients with different reperfusion strategies were compared. Among patients with fibrinolysis, two subgroups were identified according to whether successful clinical reperfusion was achieved. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR) and were compared using analysis of variance, unpaired Student’s t-test, or Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages and were compared using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate logistic regression and Cox regression were used to test associations between different reperfusion strategies and in-hospital and 2-year all-cause death, respectively. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI were estimated. The variables included in the multivariable model were either statistically significant in the univariate analysis (P < 0.05) or deemed clinically critical. Based on this methodology, the final model included the following covariates: age (≤ 60 vs. > 60 years), sex, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, time to reperfusion (< 3 vs. ≥ 3 h), Killip class (≥ II vs. I), and anterior myocardial infarction (MI). For the fibrinolytic-treated population, the multivariate analysis also incorporated the use of fibrin-specific agents.

Two-sided P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise stated, all analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS INSTITUTE INC, Cary, NC, USA).

-

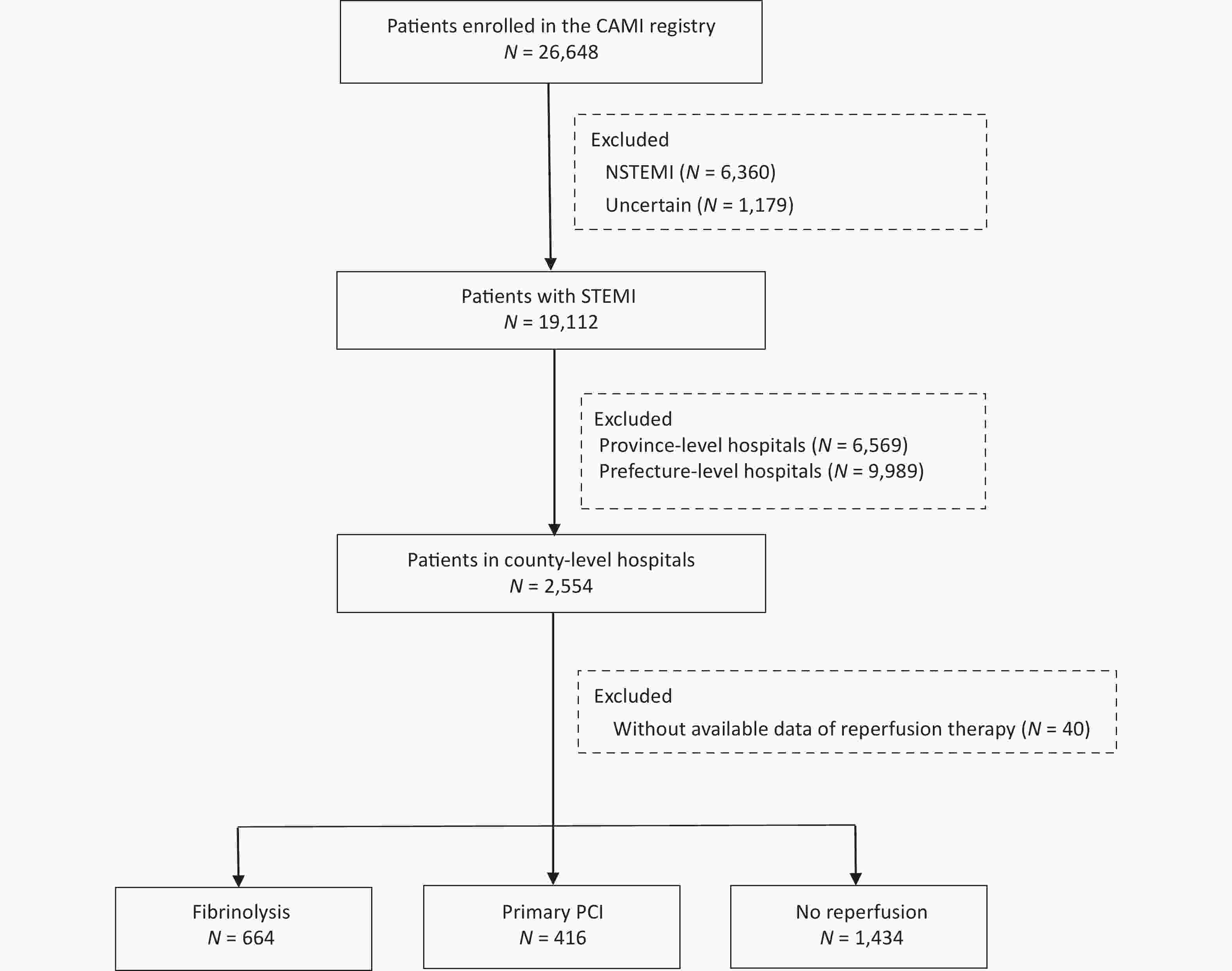

In total, 19,112 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of STEMI were consecutively enrolled from January 2013 to December 2014. Of these, 2,554 were admitted to county-level hospitals. After further exclusion of 40 patients with missing data on reperfusion therapy, 2,514 patients were included in the core cohort for the analysis (Figure 1).

-

A total of 1,080 patients (43.0%) received reperfusion therapy, 664 (62.0%) underwent fibrinolysis, and 416 (38.0%) were treated with primary PCI. Fibrinolytic agents used included reteplase (44.0%), urokinase (40.0%), and alteplase (16.0%). The type of fibrinolytic agent was not documented in 12 patients (< 2.0%). At admission, most of the study cohort were self-transported rather than calling an ambulance, and a vast majority received guideline-recommended antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies, as well as statins.

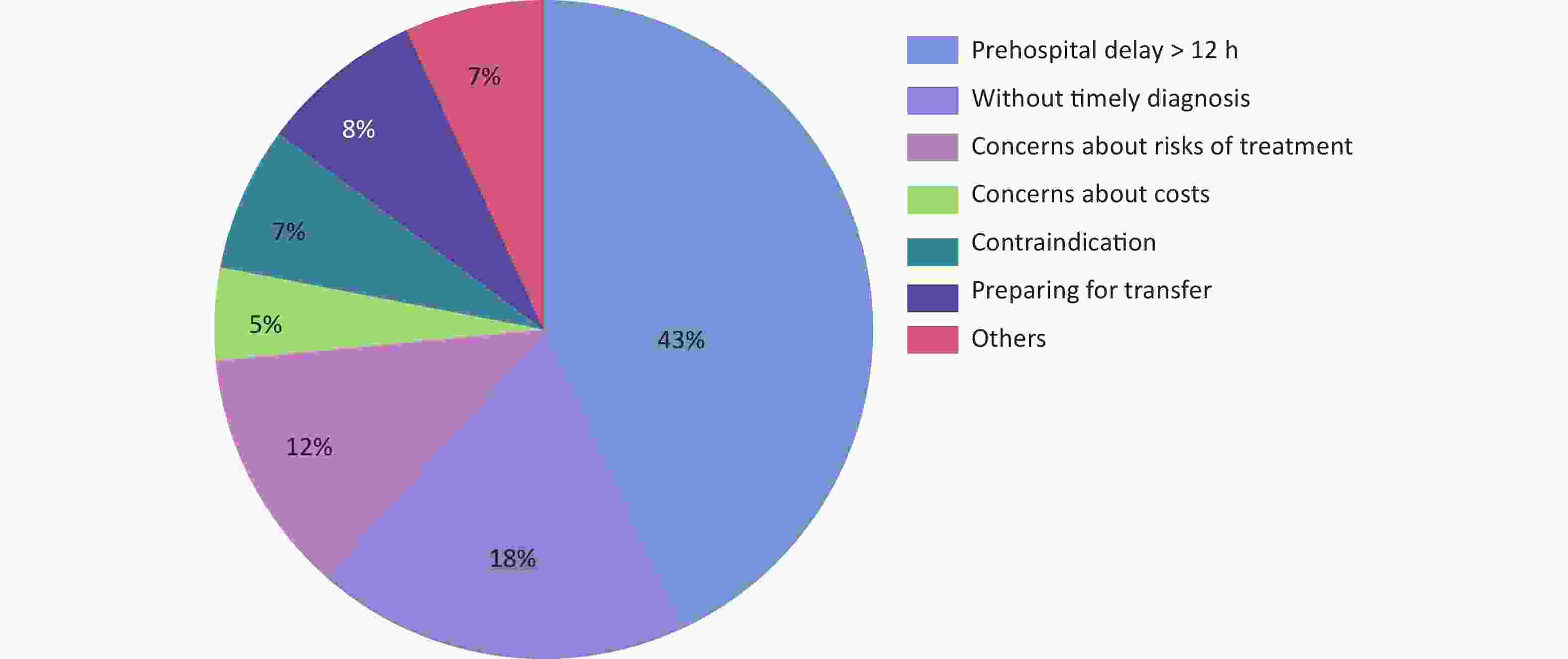

Patients without reperfusion therapy had an initial profile that was distinctly different from that of patients with either type of reperfusion treatment (Table 1). This subgroup was older and more likely to have a Killip class ≥ II and anterior MI. The reasons for missing reperfusion therapy are detailed in Figure 2. Prehospital delay > 12 h was the most common reason (43.0%), followed by missing timely diagnosis (18.0%) and concerns about the treatment risk (12.0%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of the study cohort

Characteristics Fibrinolysis (n = 664) Primary PCI (n = 416) No reperfusion (n = 1,434) Poverall Pa Age, years, M (P25–P75) 61 (53–69) 60 (51–68) 68 (59–77) < 0.001 0.181 ≤ 60, n (%) 297/664 (45) 203/416 (49) 392/1,434 (27) < 0.001 0.192 Male, n (%) 493/664 (74) 317/416 (76) 917/1,434 (64) < 0.001 0.469 Hypertension, n (%) 280/664 (42) 209/416 (50) 653/1434 (46) 0.035 0.010 Diabetes, n (%) 71/664 (11) 73/416 (18) 200/1,434 (14) 0.006 0.001 Current smoking, n (%) 301/664 (45) 247/416 (59) 484/1,434 (34) < 0.001 < 0.001 Prior MI, n (%) 38/664 (6) 19/416 (5) 86/1,434 (6) 0.524 0.404 Prior stroke, n (%) 43/664 (7) 38/416 (9) 154/1,434 (11) 0.006 0.110 Heart rate, bpm* 73 (60–85) 72 (62–82) 78 (67–92) < 0.001 0.476 SBP, mmHg* 130 (110–149) 126 (110–140) 130 (110–147) 0.058 0.018 Killip class ≥ II, n (%)* 135/664 (20) 48/416 (12) 406/1,434 (28) < 0.001 0.001 eGFR, M (P25–P75) mL/(min∙1.73 m2)* 84 (63–108) 98 (72–135) 68 (47–94) 0.131 < 0.001 LVEF, n (%)* 54 (48–60) 56 (51–64) 53 (45–60) < 0.001 < 0.001 Anterior MI, n (%) 339/664 (51) 200/416 (48) 802/1,434 (56) 0.007 0.341 Total ischemic time, min†, M (P25–P75) 222 (120–306) 246 (222–366) NA NA 0.053 < 3 h, n (%) 264/664 (40) 123/416 (30) NA NA < 0.001 < 12 h, n (%) 647/664 (97) 385/416 (93) NA NA < 0.001 Prehospital delay > 12 h, n (%) 26/663 (4) 24/416 (6) 748/1,434 (51) < 0.001 0.211 Hospital approaching method, n (%) < 0.001 0.006 Self-transport 537/661 (81) 334/414 (80) 1,199/1,431 (84) By ambulance 117/661 (18) 78/414 (19) 211/1,431 (15) On site 7/661 (1) 2/414 (1) 21/1,431 (1) In-hospital medications, n (%) Aspirin 655/664 (99) 416/416 (100) 1,355/1,434 (95) < 0.001 0.015 P2Y12 inhibitor 632/664 (95) 411/416 (99) 1,311/1,434 (91) < 0.001 < 0.001 GPI 29/664 (4) 233/416 (56) 153/1,434 (11) < 0.001 < 0.001 LMWH 574/664 (86) 388/416 (93) 1,232/1,434 (86) < 0.001 < 0.001 β-blocker 434/664 (65) 311/416 (75) 891/1,434 (62) 0.001 0.001 Statins 622/664 (94) 383/416 (92) 1,350/1,434 (94) 0.328 0.315 Diuretics 131/661 (20) 65/395 (17) 452/1,422 (32) < 0.001 0.171 Nitrates 573/662 (87) 289/395 (73) 1,215/1,422 (85) < 0.001 < 0.001 Calcium antagonists 82/660 (12) 23/394 (6) 194/1,422 (14) < 0.001 < 0.001 ACEI/ARB 394/660 (60) 250/395 (63) 868/1,424 (60) 0.371 0.123 In-hospital outcomes, n (%) Death 57/664 (8.6) 15/416 (3.6) 248/1,434 (17.3) < 0.001 < 0.001 Reinfarction 15/664 (2.3) 3/416 (0.7) 25/1,431 (1.7) 0.124 0.041 Stroke 9/664 (1.4) 2/416 (0.5) 17/1,432 (1.2) 0.313 0.220 Major bleeding# 3/664 (0.5) 3/416 (0.7) 3/1,434 (0.2) 0.304 0.681 Note. Data are reported as median (interquartile range) or number/total number [n (%)]. *Measured on admission; †Defined as the symptom onset-to-balloon time for primary PCI and the symptom onset-to-needle time for fibrinolysis; #Including any fatal or life-threatening bleeding or bleeding associated with a 5-g/dL fall in hemoglobin or intracranial bleeding. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not available; GPI, glycoprotein IIb–IIIa inhibitors; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blockers. aP, Fibrinolysis vs. Primary PCl. Compared to the fibrinolysis cohort, patients who underwent primary PCI had a similar median age and sex ratio but higher rates of cardiovascular risk factors (including diabetes, hypertension, and current smoking) (Table 1). The median (IQR) total ischemic time was 222 (120–306) min for fibrinolysis and 246 (222–366) min for primary PCI. There were significantly more patients treated within the recommended cut-off limits (< 3 h) in the fibrinolysis group than in the primary PCI group (40.0% vs. 30.0%, P < 0.001).

Of the 664 fibrinolytic-treated patients, 510 (77%) achieved successful clinical reperfusion (Table 2). Patients with successful fibrinolysis were more likely to be 60 years or younger, less likely to exhibit signs of heart failure (Killip class ≥ II) on admission, and have more frequent use of fibrin-specific agents than patients with failed fibrinolysis. The median left ventricular ejection fraction was higher in patients with successful fibrinolysis than those with failed fibrinolysis (55.0% vs. 51.0%, P = 0.011). After treatment, only 44 (9.0%) patients with successful fibrinolysis and 26 (17.0%) with failed fibrinolysis underwent PCI within 24 h from onset (Table 2).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of fibrinolytic-treated patients

Characteristics Successful fibrinolysis (n = 510) Failed fibrinolysis (n = 154) P Age, years, M (P25–P75) 61 (52–69) 62 (55–69) 0.275 ≤ 60, n (%) 240/510 (47.0) 57/154 (37) 0.027 Male, n (%) 387/510 (76) 106/154 (69) 0.084 Hypertension, n (%) 211/510 (41) 69/154 (45) 0.451 Diabetes, n (%) 51/510 (10) 20/154 (13) 0.303 Current smoking, n (%) 239/510 (47) 62/154 (40) 0.148 Prior MI, n (%) 32/510 (6) 6/154 (4) 0.246 Prior stroke, n (%) 31/510 (6) 12/154 (8) 0.458 Heart rate, bpm*, M ( P25–P75), 72 (62–85) 75 (60–87) 0.713 SBP, mmHg*, M (P25–P75) 130 (111–150) 127 (110–143) 0.132 Killip class ≥ II, n (%)* 89/510 (18) 46/154 (30) 0.001 eGFR, mL/(min∙1.73 m2)*, M (P25–P75) 85 (63–108) 86 (62–108) 0.630 LVEF, n (%)* 55 (50–61) 51 (45–58) 0.011 Anterior MI, n (%) 251/510 (49) 88/154 (57) 0.084 Symptom to needle time, min, M (P25–P75) 183 (122–244) 244 (183–366) 0.956 < 3 h, n (%) 221/510 (43) 43/154 (28) < 0.001 Prehospital delay > 12 h, n (%) 15/509 (3) 11/154 (7) < 0.001 In-hospital medications, n (%) Aspirin 505/510 (99) 150/154 (97) 0.224 P2Y12 inhibitor 489/510 (96) 143/154 (93) 0.141 LMWH 458/510 (90) 116/154 (75) < 0.001 β-blocker 350/510 (69) 84/154 (55) 0.002 Statins 477/510 (94) 145/154 (94) 0.778 Diuretics 91/508 (18) 40/153 (26) 0.029 Nitrates 459/508 (90) 114/154 (74) < 0.001 Calcium antagonists 65/506 (13) 17/154 (11) 0.547 ACEI/ARB 318/506 (63) 76/154 (49) 0.011 Fibrinolytic agents, n (%) < 0.001 Urokinase 186/503 (37) 75/149 (50) Alteplase 72/503 (14) 33/149 (22) Reteplase 245/503 (49) 41/149 (28) Post treatment, n (%) 0.005 Medications 466/510 (91) 128/154 (83) PCI within 24 h from onset 44/510 (9) 26/154 (17) In-hospital outcomes, n (%) Death 20/510 (3.9) 37/154 (24.0) < 0.001 Reinfarction 10/510 (2.0) 5/154 (3.2) 0.357 Stroke 6/510 (1.2) 3/154 (1.9) 0.440 Major bleeding# 2/510 (0.4) 1/154 (0.6) 0.548 Note. Data are reported as median (interquartile range) or number/total number (n (%)). *Measuring on admission; #Including any fatal or life-threatening bleeding or bleeding associated with a 5-g/dL fall in hemoglobin or intracranial bleeding. MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blockers; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. -

In-hospital mortality was the highest in patients without reperfusion therapy (17.3%); it was 8.6% in patients with fibrinolysis and 3.6% in those with primary PCI. Multivariate logistic analysis showed that both fibrinolysis (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.34–0.91, P = 0.021) and primary PCI (OR = 0.22, 95% CI: 0.11–0.44, P < 0.001) were associated with reduced all-cause mortality during hospitalization compared to no reperfusion therapy (Table 3). Other in-hospital outcomes were similar in patients with different reperfusion strategies, except reinfarction, which was more common in the fibrinolysis group than the primary PCI group (2.3% vs. 0.7%, P = 0.041). Major bleeding was rare among the three groups (Table 1).

Table 3. Association of different reperfusion strategies on all-cause death

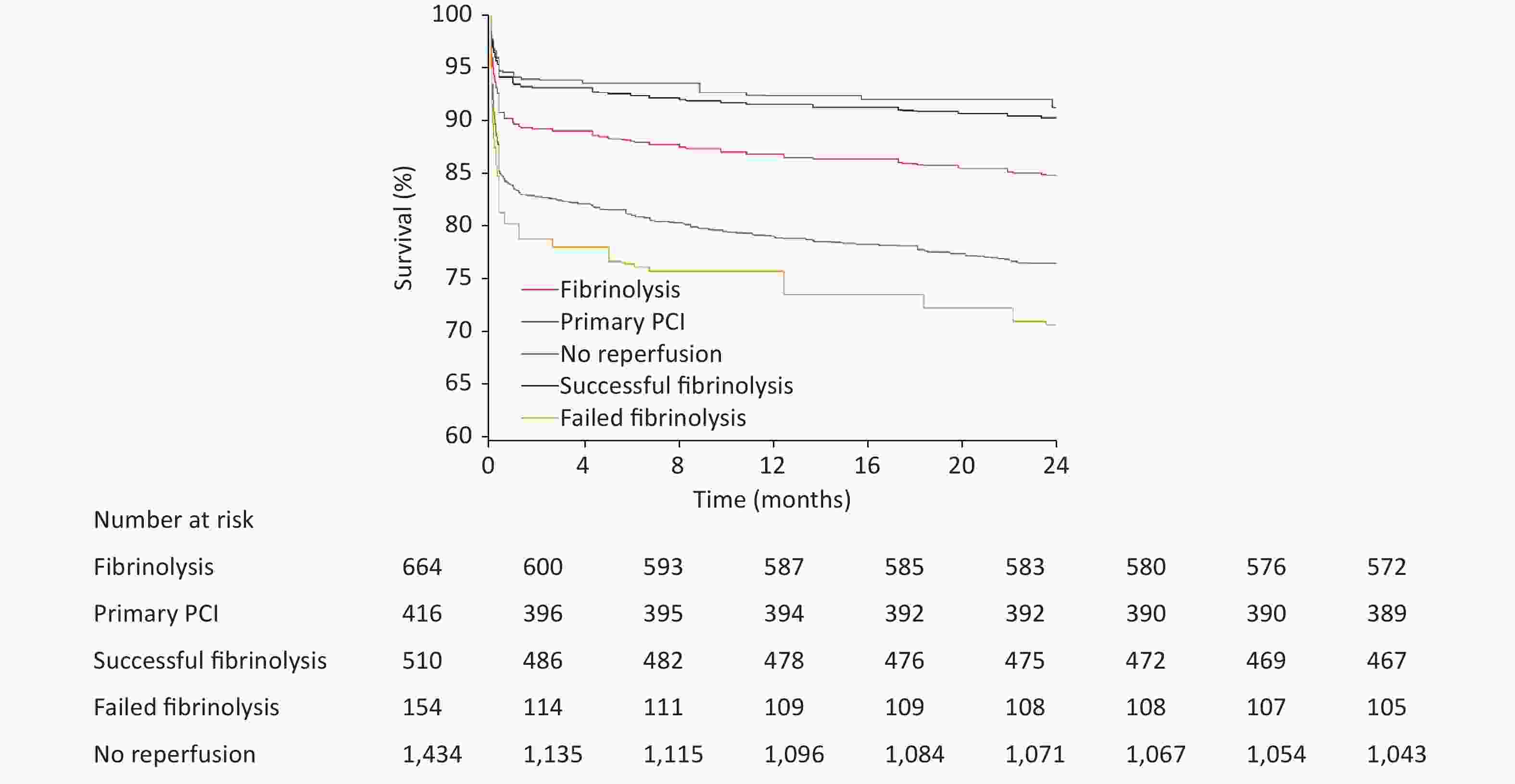

Reperfusion strategy In hospital 2 years OR (95% CI) P HR (95% CI) P Comparing with no reperfusion Fibrinolysis* 0.55 (0.34–0.91) 0.021 0.59 (0.44–0.80) < 0.001 Successful fibrinolysis* 0.50 (0.26–0.96) 0.036 0.36 (0.25–0.54) < 0.001 Failed fibrinolysis* 0.59 (0.22–1.15) 0.103 1.30 (0.93–1.81) 0.125 Primary PCI† 0.22 (0.11–0.44) < 0.001 0.32 (0.22–0.48) < 0.001 Comparing with primary PCI Fibrinolysis* 2.11 (1.02–4.36) 0.044 2.09 (1.25–3.49) 0.005 Successful fibrinolysis* 1.83 (0.77–4.36) 0.170 1.53 (0.85–2.73) 0.155 Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. *Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, total ischemic time, Killip class, anterior myocardial infarction, and use of fibrin-specific agents. †Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, total ischemic time, Killip class, and anterior myocardial infarction. The 2-year follow-up data were available for 2,407 patients (94.2%), with 510 deaths (21.2%): 391 (28.5%) for no reperfusion, 92 (14.5%) for fibrinolysis, and 27 (6.8%) for primary PCI (Figure 3). After Cox multivariate analysis, both fibrinolysis (HR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.44–0.80) and primary PCI (HR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.22–0.48) predicted lower mortality at 2 years than no reperfusion therapy (Table 3).

Among fibrinolytic-treated patients, a relatively benign survival outcome was observed among patients with successful fibrinolysis, in whom the cumulative rates of death during hospitalization and 2 years were 3.9% and 8.8%, respectively. Conversely, in patients with failed fibrinolysis, the in-hospital and 2-year death rates were 24.0% and 33.1%, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 3). Successful fibrinolysis was associated with similar in-hospital (OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 0.77–4.36, P = 0.170) and 2-year mortality to primary PCI (HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 0.85–2.73) (Table 3). Failed fibrinolysis, however, shared a similar in-hospital (OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.22–1.15, P = 0.103) and 2-year (HR = 1.30, 95% CI: 0.93–1.81, P = 0.125) mortality to no reperfusion.

-

In Chinese county-level hospitals, over half of the patients with STEMI admitted within 7 days from symptom onset did not receive reperfusion therapy; notably, nearly 30% in this group died during a 2-year follow-up. The most common reason for missing reperfusion therapy was a prehospital delay. Approximately 23% of fibrinolytic-treated patients could not achieve successful clinical reperfusion, but only 17% underwent rescue PCI; in this group, up to 1/3 did not survive during the 2-year follow-up. In contrast, 2-year mortality in patients with successful fibrinolysis was < 9%, similar to those with primary PCI. These results mainly suggest that: 1) In Chinese county-level hospitals, enhancing public education for recognizing STEMI symptoms and emergency medical system (EMS) capacity should be prioritized to reduce prehospital delay and improve patient eligibility for reperfusion therapy; 2) fast referral for mechanical revascularization in case of failed fibrinolysis should be emphasized.

Previously, a group of studies reported medical care for STEMI among patients living in rural China. The China Patient-centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (PEACE)-Retrospective AMI study reported increasing use of reperfusion therapy among eligible patients with STEMI (symptom onset to admission within 12 h) admitted to rural hospitals from 2001 to 2011 (47.0% to 57.0%)[3]. The China Chest Pain Center Quality Control Report (2021) also investigated patients with STEMI admitted to chest pain centers without primary PCI capability within 12 h of symptom onset; 85.6% of them received reperfusion therapy[4]. A substudy of the CPACS-3 (third phase of the Clinical Pathways for Acute Coronary Syndromes in China) studied 7,312 patients with STEMI among 101 non-PCI hospitals (mostly located in rural areas) in China from 2011 to 2014 and found that 3,057 (41.8%) received reperfusion therapy[5]. These results share an important limitation in that data obtained from either ideal patients for treatment or only fibrinolytic-treated patients could not represent the use of reperfusion therapy in the entire rural population with STEMI. Other province-wide registry studies, which reported reperfusion therapy and outcomes for STEMI among reperfusion-capable hospitals in rural China, were restricted to relatively small samples or short follow-up periods[6,7].

In the CAMI registry, patients with a primary diagnosis of AMI, including STEMI, admitted to participating hospitals within 7 days after the onset of ischemic symptoms were consecutively enrolled. In the present study, approximately 57.0% of the study population did not receive reperfusion therapy. Although other registry studies reported that the use of reperfusion therapy in rural areas increased in a more recent year (54.0% for Liaoning province in 2015 and 62.0% for Henan province in 2018)[6,7], such data were far behind other real-world reports in rural settings from developed countries (84.0% to 87.0%)[13-15]. During the 2-year follow-up, nearly 30.0% of patients with no reperfusion did not survive, accounting for 77.0% of the total deaths in the present study. These findings highlight the need for a national quality improvement initiative with a clear focus on improving the use of reperfusion therapy in county-level hospitals to reduce the burden of AMI in rural China.

In the present study, the major barrier to using reperfusion therapy in county-level hospitals was the lack of eligibility due to the exceeded therapeutic time window, largely due to the prehospital delay. This may be attributable to patient factors (including poor knowledge of STEMI symptoms and not calling EMS when symptoms occur) and systemic factors (including limited EMS capacity)[16]. The missing timely diagnosis seemed to be another important issue, and the reasons for this may be complicated. The possible lack of diagnostic procedures within standard timing should be considered, given that the first electrocardiograph (ECG) delay (time from arrival to first ECG > 10 min) among hospitals in rural China has been reported[5]. Another possibility is that some patients with STEMI are on admission with relief of chest pain or ST-segment resolution. Additionally, some physicians in Chinese county-level hospitals cannot recognize atypic myocardial ischemic symptoms and ECG. This finding shows the necessity to improve further the ability of primary care physicians to recognize chest pain and diagnose STEMI for a faster offering of reperfusion therapy.

Over the past few decades, fibrinolysis has been the mainstay of reperfusion therapy for STEMI in rural China[6-8]. However, the long-term prognosis among fibrinolytic-treated patients in this setting has not been previously studied. With most patients with fibrinolysis achieving successful clinical reperfusion in the present study, there was no difference in the 2-year all-cause mortality between successful fibrinolysis and primary PCI. A previous survey of the CAMI registry demonstrated that using fibrin-specific agents and shorter total ischemic time are independent predictors of successful fibrinolysis[17]; encouragingly, both of which have significantly improved in rural China over the past decades. In the China PEACE-Retrospective AMI study, > 90.0% of the fibrinolytic-treated patients received urokinase[3]. In our study, fibrin-specific agents became the mainstay (including alteplase and reteplase, approximately 60%). In the recent Henan STEMI registry, up to 95.1% were treated with specific fibrinolytic agents, and the onset-to-fibrinolysis time (190 [130–285] min) was shorter than in the present study[7]. Such improvements suggest that successful clinical reperfusion after fibrinolysis could increasingly be achieved in treated patients in rural China, predicting an improved long-term prognosis.

Routine angiography with subsequent PCI within 24 h was only performed in a few patients with successful fibrinolysis. It is well established that early routine PCI after successful fibrinolysis in STEMI patients significantly reduces reinfarction and recurrent ischemia during short- and long-term follow-up, with no significant increase in adverse bleeding events compared to standard therapy limiting PCI only to patients without evidence of reperfusion[18,19]. This pharmacoinvasive strategy has been the recommended standard of care after successful fibrinolysis[20]. It is noteworthy that the implementation of such a pharmacoinvasive strategy needs to have an organized network and coordinated STEMI reperfusion protocol[13,21], which is the purpose of the China Chest Pain Center project[22]. Although the establishment of chest pain care units in primary healthcare institutions has been initiated to improve the management and in-hospital outcomes, only 1,049 have been accredited by the end of 2021[4], far behind the number of county-level hospitals calculated in 2020 (n = 16,800)[23]. Establishing an organized STEMI network remains challenging in China and other developing countries and newly industrialized nations[24]. In the present study, relatively benign short- and long-term survival outcomes in the successful fibrinolysis group were observed, suggesting that in regions with limited healthcare provision and unbalanced economic development, medical therapy after fibrinolysis for those with successful clinical reperfusion might be acceptable. Given the clinical and socioeconomic impact of a pharmacoinvasive approach on major adverse cardiovascular events, future large-scale randomized studies need to be conducted, particularly across various risk subgroups.

For patients with failed fibrinolysis, the substantial shortfall of rescue PCI appears to be a particularly important issue, which might largely explain the extremely poor 2-year survival outcomes. This finding demonstrated that the management of patients with failed fibrinolysis must include rescue PCI to improve long-term prognosis. Given that only a small part of county-level hospitals have been equipped with PCI facilities and are qualified for performing primary PCI, strategies targeting the fast transfer of this population to higher-level hospitals should be emphasized.

The long-term prognosis of patients with primary PCI admitted to county-level hospitals has never been investigated. It is unknown whether the effectiveness of primary PCI may have been diminished by operators with relatively insufficient experience, technique, and case mix in county-level hospitals due to the relatively lower annual STEMI admission and poorer capacity for cardiovascular intervention in AMI[25,26]. In the present study, long-term (12 months) mortality in the primary PCI group was comparable with other large real-world studies from centers with a high volume of PCI procedures[27,28], indicating that primary PCI has been effectively used in Chinese county-level hospitals. Improving PCI-related infrastructure and training interventional physicians qualified for performing primary PCI are necessary to increase the use of primary PCI further.

Our study had several limitations. First, the CAMI registry data were collected nearly 10 years ago. They may not reflect the current quality of STEMI care in county-level hospitals, which has not been studied in recent years and needs further investigation. Furthermore, there is no standardized measurement for laboratory tests, especially for myocardial infarction markers, across different levels in Chinese hospitals. Second, the number of patients with reperfusion therapy in our study was relatively small to address all issues discussed, characterize other subtle biases, and perform multivariate analysis regarding baseline characteristics. Third, we could not obtain the cause of death and other data regarding other major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events during long-term follow-up, including recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure. Fourth, it should be noted that non-invasive markers were utilized in this study to assess the efficacy of fibrinolysis; thus, the evaluation of recanalization effect may be overestimated compared to that obtained through coronary angiography[17,29]. Finally, as an observational study, although several statistical adjustments were performed, we could not exclude the presence of unmeasured selection bias. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable real-world data on the long-term prognosis of patients with STEMI treated with different reperfusion strategies in county-level hospitals. This information might be significant for making therapeutic decisions for patients with STEMI in rural China and informing future healthcare quality improvement and medical resource allocation strategies for policymakers and medical professionals in China and other developing countries.

-

Among county-level hospitals that participated in the CAMI registry, the use of reperfusion therapy for STEMI was substantially short, largely because of prehospital delay. Nearly 30% of patients without reperfusion therapy did not survive during the 2-year follow-up, accounting for a major part of the total death. Medical therapy after treatment seemed acceptable among patients with successful fibrinolysis, given that a relatively benign long-term survival outcome was observed in this group, similar to those with primary PCI. Approximately 1/3 of patients with failed fibrinolysis did not survive for 2 years, mainly due to the lack of rescue PCI. There is an urgent need in rural China to enhance public awareness of STEMI symptoms, increase EMS capacity, and establish an integrated regional network for patient referral to PCI hospitals.

doi: 10.3967/bes2023.110

Long-Term Prognosis of Different Reperfusion Strategies for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Chinese County-Level Hospitals: Insight from China Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry

-

Abstract:

Objective To evaluate the long-term prognosis of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated with different reperfusion strategies in Chinese county-level hospitals Methods A total of 2,514 patients with STEMI from 32 hospitals participated in the China Acute Myocardial Infarction registry between January 2013 and September 2014. The success of fibrinolysis was assessed according to indirect measures of vascular recanalization. The primary outcome was 2-year mortality. Results Reperfusion therapy was used in 1,080 patients (42.9%): fibrinolysis (n = 664, 61.5%) and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (n = 416, 38.5%). The most common reason for missing reperfusion therapy was a prehospital delay > 12 h (43%). Fibrinolysis [14.5%, hazard ratio (HR): 0.59, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44–0.80] and primary PCI (6.8%, HR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.22–0.48) were associated with lower 2-year mortality than those with no reperfusion (28.5%). Among fibrinolysis-treated patients, 510 (76.8%) achieved successful clinical reperfusion; only 17.0% of those with failed fibrinolysis underwent rescue PCI. There was no difference in 2-year mortality between successful fibrinolysis and primary PCI (8.8% vs. 6.8%, HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 0.85–2.73). Failed fibrinolysis predicted a similar mortality (33.1%) to no reperfusion (33.1% vs. 28.5%, HR = 1.30, 95% CI: 0.93–1.81). Conclusion In Chinese county-level hospitals, only approximately 2/5 of patients with STEMI underwent reperfusion therapy, largely due to prehospital delay. Approximately 30% of patients with failed fibrinolysis and no reperfusion therapy did not survive at 2 years. Quality improvement initiativesare warranted, especially in public health education and fast referral for mechanical revascularization in cases of failed fibrinolysis. -

Key words:

- Acute myocardial infarction /

- Reperfusion therapy /

- Rural /

- Outcome

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) AUTHOR STATEMENT: -

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of the study cohort

Characteristics Fibrinolysis (n = 664) Primary PCI (n = 416) No reperfusion (n = 1,434) Poverall Pa Age, years, M (P25–P75) 61 (53–69) 60 (51–68) 68 (59–77) < 0.001 0.181 ≤ 60, n (%) 297/664 (45) 203/416 (49) 392/1,434 (27) < 0.001 0.192 Male, n (%) 493/664 (74) 317/416 (76) 917/1,434 (64) < 0.001 0.469 Hypertension, n (%) 280/664 (42) 209/416 (50) 653/1434 (46) 0.035 0.010 Diabetes, n (%) 71/664 (11) 73/416 (18) 200/1,434 (14) 0.006 0.001 Current smoking, n (%) 301/664 (45) 247/416 (59) 484/1,434 (34) < 0.001 < 0.001 Prior MI, n (%) 38/664 (6) 19/416 (5) 86/1,434 (6) 0.524 0.404 Prior stroke, n (%) 43/664 (7) 38/416 (9) 154/1,434 (11) 0.006 0.110 Heart rate, bpm* 73 (60–85) 72 (62–82) 78 (67–92) < 0.001 0.476 SBP, mmHg* 130 (110–149) 126 (110–140) 130 (110–147) 0.058 0.018 Killip class ≥ II, n (%)* 135/664 (20) 48/416 (12) 406/1,434 (28) < 0.001 0.001 eGFR, M (P25–P75) mL/(min∙1.73 m2)* 84 (63–108) 98 (72–135) 68 (47–94) 0.131 < 0.001 LVEF, n (%)* 54 (48–60) 56 (51–64) 53 (45–60) < 0.001 < 0.001 Anterior MI, n (%) 339/664 (51) 200/416 (48) 802/1,434 (56) 0.007 0.341 Total ischemic time, min†, M (P25–P75) 222 (120–306) 246 (222–366) NA NA 0.053 < 3 h, n (%) 264/664 (40) 123/416 (30) NA NA < 0.001 < 12 h, n (%) 647/664 (97) 385/416 (93) NA NA < 0.001 Prehospital delay > 12 h, n (%) 26/663 (4) 24/416 (6) 748/1,434 (51) < 0.001 0.211 Hospital approaching method, n (%) < 0.001 0.006 Self-transport 537/661 (81) 334/414 (80) 1,199/1,431 (84) By ambulance 117/661 (18) 78/414 (19) 211/1,431 (15) On site 7/661 (1) 2/414 (1) 21/1,431 (1) In-hospital medications, n (%) Aspirin 655/664 (99) 416/416 (100) 1,355/1,434 (95) < 0.001 0.015 P2Y12 inhibitor 632/664 (95) 411/416 (99) 1,311/1,434 (91) < 0.001 < 0.001 GPI 29/664 (4) 233/416 (56) 153/1,434 (11) < 0.001 < 0.001 LMWH 574/664 (86) 388/416 (93) 1,232/1,434 (86) < 0.001 < 0.001 β-blocker 434/664 (65) 311/416 (75) 891/1,434 (62) 0.001 0.001 Statins 622/664 (94) 383/416 (92) 1,350/1,434 (94) 0.328 0.315 Diuretics 131/661 (20) 65/395 (17) 452/1,422 (32) < 0.001 0.171 Nitrates 573/662 (87) 289/395 (73) 1,215/1,422 (85) < 0.001 < 0.001 Calcium antagonists 82/660 (12) 23/394 (6) 194/1,422 (14) < 0.001 < 0.001 ACEI/ARB 394/660 (60) 250/395 (63) 868/1,424 (60) 0.371 0.123 In-hospital outcomes, n (%) Death 57/664 (8.6) 15/416 (3.6) 248/1,434 (17.3) < 0.001 < 0.001 Reinfarction 15/664 (2.3) 3/416 (0.7) 25/1,431 (1.7) 0.124 0.041 Stroke 9/664 (1.4) 2/416 (0.5) 17/1,432 (1.2) 0.313 0.220 Major bleeding# 3/664 (0.5) 3/416 (0.7) 3/1,434 (0.2) 0.304 0.681 Note. Data are reported as median (interquartile range) or number/total number [n (%)]. *Measured on admission; †Defined as the symptom onset-to-balloon time for primary PCI and the symptom onset-to-needle time for fibrinolysis; #Including any fatal or life-threatening bleeding or bleeding associated with a 5-g/dL fall in hemoglobin or intracranial bleeding. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not available; GPI, glycoprotein IIb–IIIa inhibitors; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blockers. aP, Fibrinolysis vs. Primary PCl. Table 2. Baseline characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of fibrinolytic-treated patients

Characteristics Successful fibrinolysis (n = 510) Failed fibrinolysis (n = 154) P Age, years, M (P25–P75) 61 (52–69) 62 (55–69) 0.275 ≤ 60, n (%) 240/510 (47.0) 57/154 (37) 0.027 Male, n (%) 387/510 (76) 106/154 (69) 0.084 Hypertension, n (%) 211/510 (41) 69/154 (45) 0.451 Diabetes, n (%) 51/510 (10) 20/154 (13) 0.303 Current smoking, n (%) 239/510 (47) 62/154 (40) 0.148 Prior MI, n (%) 32/510 (6) 6/154 (4) 0.246 Prior stroke, n (%) 31/510 (6) 12/154 (8) 0.458 Heart rate, bpm*, M ( P25–P75), 72 (62–85) 75 (60–87) 0.713 SBP, mmHg*, M (P25–P75) 130 (111–150) 127 (110–143) 0.132 Killip class ≥ II, n (%)* 89/510 (18) 46/154 (30) 0.001 eGFR, mL/(min∙1.73 m2)*, M (P25–P75) 85 (63–108) 86 (62–108) 0.630 LVEF, n (%)* 55 (50–61) 51 (45–58) 0.011 Anterior MI, n (%) 251/510 (49) 88/154 (57) 0.084 Symptom to needle time, min, M (P25–P75) 183 (122–244) 244 (183–366) 0.956 < 3 h, n (%) 221/510 (43) 43/154 (28) < 0.001 Prehospital delay > 12 h, n (%) 15/509 (3) 11/154 (7) < 0.001 In-hospital medications, n (%) Aspirin 505/510 (99) 150/154 (97) 0.224 P2Y12 inhibitor 489/510 (96) 143/154 (93) 0.141 LMWH 458/510 (90) 116/154 (75) < 0.001 β-blocker 350/510 (69) 84/154 (55) 0.002 Statins 477/510 (94) 145/154 (94) 0.778 Diuretics 91/508 (18) 40/153 (26) 0.029 Nitrates 459/508 (90) 114/154 (74) < 0.001 Calcium antagonists 65/506 (13) 17/154 (11) 0.547 ACEI/ARB 318/506 (63) 76/154 (49) 0.011 Fibrinolytic agents, n (%) < 0.001 Urokinase 186/503 (37) 75/149 (50) Alteplase 72/503 (14) 33/149 (22) Reteplase 245/503 (49) 41/149 (28) Post treatment, n (%) 0.005 Medications 466/510 (91) 128/154 (83) PCI within 24 h from onset 44/510 (9) 26/154 (17) In-hospital outcomes, n (%) Death 20/510 (3.9) 37/154 (24.0) < 0.001 Reinfarction 10/510 (2.0) 5/154 (3.2) 0.357 Stroke 6/510 (1.2) 3/154 (1.9) 0.440 Major bleeding# 2/510 (0.4) 1/154 (0.6) 0.548 Note. Data are reported as median (interquartile range) or number/total number (n (%)). *Measuring on admission; #Including any fatal or life-threatening bleeding or bleeding associated with a 5-g/dL fall in hemoglobin or intracranial bleeding. MI, myocardial infarction; SBP, systolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; ACEI: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blockers; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. Table 3. Association of different reperfusion strategies on all-cause death

Reperfusion strategy In hospital 2 years OR (95% CI) P HR (95% CI) P Comparing with no reperfusion Fibrinolysis* 0.55 (0.34–0.91) 0.021 0.59 (0.44–0.80) < 0.001 Successful fibrinolysis* 0.50 (0.26–0.96) 0.036 0.36 (0.25–0.54) < 0.001 Failed fibrinolysis* 0.59 (0.22–1.15) 0.103 1.30 (0.93–1.81) 0.125 Primary PCI† 0.22 (0.11–0.44) < 0.001 0.32 (0.22–0.48) < 0.001 Comparing with primary PCI Fibrinolysis* 2.11 (1.02–4.36) 0.044 2.09 (1.25–3.49) 0.005 Successful fibrinolysis* 1.83 (0.77–4.36) 0.170 1.53 (0.85–2.73) 0.155 Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. *Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, total ischemic time, Killip class, anterior myocardial infarction, and use of fibrin-specific agents. †Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, total ischemic time, Killip class, and anterior myocardial infarction. -

[1] Chang J, Liu X, Sun Y. Mortality due to acute myocardial infarction in China from 1987 to 2014: Secular trends and age-period-cohort effects. Int J Cardiol, 2017; 227, 229−38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.130 [2] The Writing Committee of the Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China. Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China 2021: An updated summary. Biomed Environ Sci, 2022; 35, 573−603. [3] Li J, Li X, Ross JS, et al. Fibrinolytic therapy in hospitals without percutaneous coronary intervention capabilities in China from 2001 to 2011: China PEACE-retrospective AMI study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, 2017; 6, 232−43. doi: 10.1177/2048872615626656 [4] China Chest Pain Center Alliance, China Cardiovascular Health Alliance et al. Summary of the China chest pain center quality control Report (2021). Chin J Intervent Cardiol, 2022; 30, 321−7. (In Chinese [5] Feng L, Li M, Xie W, et al. Prehospital and in-hospital delays to care and associated factors in patients with STEMI: an observational study in 101 non-PCI Hospitals in China. BMJ Open, 2019; 9: e031918. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031918 [6] Li GX, Zhou B, Qi GX, et al. Current trends for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction during the Past 5 Years in rural areas of China's Liaoning province: a multicenter study. Chin Med J (Engl), 2017; 130, 757−66. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.202742 [7] Zhang Y, Wang S, Cheng Q, et al. Reperfusion strategy and in-hospital outcomes for ST elevation myocardial infarction in secondary and tertiary hospitals in predominantly rural central China: a multicentre, prospective and observational study. BMJ Open, 2021; 11, e053510. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053510 [8] Xu HY, Yang YJ, Wang CS, et al. Association of hospital-level differences in care with outcomes among patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China. JAMA Netw Open, 2020; 3, e2021677. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21677 [9] Xu HY, Li W, Yang JG, et al. The China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) Registry: A national long-term registry-research-education integrated platform for exploring acute myocardial infarction in China. Am Heart J, 2016; 175, 193-201. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.014 [10] Sun H, Yang YJ, Xu HY, et al. Survey of medical care resources of acute myocardial infarction in different regions and levels of hospitals in China. Chin J Cardiol, 2016; 44, 565−9. (In Chinese [11] Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Glob Heart, 2012; 7, 275−95. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.08.001 [12] Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association, Editorial board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Chin J Cardiol, 2010; 38, 675−690. (In Chinese [13] Shavadia J, Ibrahim Q, Sookram S, et al. Bridging the gap for nonmetropolitan STEMI patients through implementation of a pharmacoinvasive reperfusion strategy. Canad J Cardiol, 2013; 29, 951−9. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.10.018 [14] Masuda J, Kishi M, Kumagai N, et al. Rural-urban disparity in emergency care for acute myocardial infarction in Japan. Circ J, 2018; 82: 1666−74. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-1275 [15] Hillerson D, Li S, Misumida N, et al. Characteristics, process metrics, and outcomes among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in rural vs urban areas in the US: a report from the US national cardiovascular data registry. JAMA Cardiol, 2022; 7, 1016−24. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2774 [16] Yin XJ, He YB, Zhang J, et al. Patient-level and system-level barriers associated with treatment delays for ST elevation myocardial infarction in China. Heart, 2020; 106, 1477−82. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-316621 [17] Wu C, Zhang XY, Yu M, et al. Analysis of in-hospital outcome of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing various thrombolytic strategies in China. Chin Circulat J, 2021; 36, 1070−76. (In Chinese [18] Borgia F, Goodman SG, Halvorsen S, et al. Early routine percutaneous coronary intervention after fibrinolysis vs. standard therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J, 2010; 31, 2156−69. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq204 [19] D'Souza SP, Mamas MA, Fraser DG, et al. Routine early coronary angioplasty versus ischaemia-guided angioplasty after thrombolysis in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J, 2011; 32, 972−82. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq398 [20] Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J, 2017; 39, 119−77. [21] Larson DM, Duval S, Sharkey SW, et al. Safety and efficacy of a pharmaco-invasive reperfusion strategy in rural ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients with expected delays due to long-distance transfers. Eur Heart J, 2012; 33, 1232−40. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr403 [22] Zhang Y, Yu B, Han Y, et al. Protocol of the China ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) Care Project (CSCAP): a 10-year project to improve quality of care by building up a regional STEMI care network. BMJ Open, 2019; 9, e026362. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026362 [23] National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. China public health statistical yearbook 2020. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Publishing House. 2021. (In Chinese [24] Huber K, Gersh BJ, Goldstein P, et al. The organization, function, and outcomes of ST-elevation myocardial infarction networks worldwide: current state, unmet needs and future directions. Eur Heart J, 2014; 35, 1526−32. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu125 [25] West RM, Cattle BA, Bouyssie M, et al. Impact of hospital proportion and volume on primary percutaneous coronary intervention performance in England and Wales. Eur Heart J, 2011; 32, 706−11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq476 [26] Doll JA, Nelson AJ, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention operator profiles and associations with in-hospital mortality. Circul Cardiovascul Intervent, 2022; 15, e010909. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.010909 [27] Danchin N, Coste P, Ferrières J, et al. Comparison of thrombolysis followed by broad use of percutaneous coronary intervention with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment-elevation acute myocardial infarction: data from the french registry on acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (FAST-MI). Circulation, 2008; 118, 268−76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.762765 [28] Stenestrand U, Lindbäck J, Wallentin L, et al. Long-term outcome of primary percutaneous coronary intervention vs prehospital and in-hospital thrombolysis for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA, 2006; 296, 1749−56. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1749 [29] Ross AM, Gao RL, Coyne KS, et al. A randomized trial confirming the efficacy of reduced dose recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in a Chinese myocardial infarction population and demonstrating superiority to usual dose urokinase: the TUCC trial. Am Heart J, 2001; 142, 244−7. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.116963 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links