-

The global aging process continues to become more pronounced, with every country worldwide experiencing an increase in both the size and proportion of older individuals in their populations[1]. China is no exception. By 2020, the number of Chinese older adults aged 60 and over had reached 264 million, accounting for 18.7% of the total population. It is expected to reach 487 million by 2050[2]. With population aging, psychological health issues among older adults have garnered increasing attention. According to the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, approximately 280 million people in the world have depression, including 5.7% of adults older than 60 years[3]. Research predicts that by 2030, depression will rank as the first cause of the burden of disease worldwide[4]. In China, depressive disorders have ranked as the second most significant contributor to years lived with disability since 2010[5], and the prevalence rate of depression in older adults is 23.6%, which is higher in other age groups[6]. As one of the common psychological health problems among older adults, depression not only negatively affects the quality of life and well-being of older individuals but also imposes a heavy burden on families and society[7,8]. Evidently, depression is not a normal part of aging but is a genuine and treatable medical condition[9] that should be taken seriously.

Social isolation is a significant risk factor for mental health problems in older adults. During global health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, prolonged isolation measures have intensified mental health challenges among older adults[10]. Historical public health events, such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in 2003, have underscored that a lack of social interaction and participation in community activities can precipitate emotional problems, including loneliness, anxiety, and depression, in this demographic[11]. The World Health Organization's concept of “active aging” posits that active social engagement is essential for older adults to maintain their social roles, identity, and access to emotional support networks, all of which contribute to their psychological well-being and preservation of good mental health[12]. Activity theory further posits that participation in social activities enables older adults to not only maintain their social roles and identity but also to acquire emotional support, thereby effectively promoting mental health[13]. For instance, the English Longitudinal Study of Aging cohort involving 6,468 adults aged ≥ 50 years showed that cultural engagement, such as attending museums, art galleries, and concerts, was associated with a 5.1% reduction in the prevalence of moderate-to-severe pain over a 6-year period. Furthermore, this reduction in pain prevalence was more pronounced in older adults who were not married or cohabiting (3.4% reduction) and in those with less frequent contact with close family members (3.9% reduction)[14]. Another study involving 229 White, Black, and Hispanic men and women aged 50–68 years found a significant negative correlation between loneliness and participation in physical activity[15]. These findings highlight the importance of encouraging social engagement to prevent the negative health consequences associated with social isolation while also proving that the benefits of social engagement are observable and significant across different cultural contexts and specific types of social engagement.

Researchers have extensively studied the impact of social engagement on mental health in older adults[16-18]. However, broader literature confirms that various forms of social engagement in old age are associated with different likelihoods of depression. For example, one study found a negative correlation between depressive symptoms and activities, such as volunteering, exercising, participating in sports, and watching movies, but no association was found between depressive symptoms and attendance at religious ceremonies or social gatherings[19]. Another study demonstrated that over time, participation in religious organizations was associated with lower depressive symptoms than other activities such as volunteering, sports, and social clubs[20]. Furthermore, a study based on the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) found three levels of social engagement among older Chinese adults: low, moderate, and high activity[21]. The moderate-activity group engaged in traditional leisure activities, whereas the high-activity group participated more in self-help activities, such as reading, playing cards, and other social activities. Compared with the low-activity group, older adults in the high-activity group exhibited better positive emotions and lower negative emotions. This result further emphasizes the different effects of various forms of social engagement on the mental health of older adults, particularly the potential benefits of active engagement in social activities in reducing depressive symptoms.

As social engagement is associated with a low risk of depression, promoting it may provide a protective effect in preventing and mitigating the onset and progression of depression at minimal cost[22,23]. However, recent studies suggest that marital status plays a crucial contextual role in the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms in older adults, which may constitute a moderating process. Many studies found that marital status is associated with the risk of depression in older adults. For example, several studies have shown that being married is a protective factor for depression worldwide[24,25]. Divorced and widowed men aged 75–85 years reportedly have a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than others[26]. A longitudinal analysis showed higher mean levels of depressive symptoms among widowed Mexican Americans[27]. In the older Irish population, depressive symptoms were more common among those who were separated, divorced, or widowed than among those who were married[28]. This is similar for middle-aged and older adults in China, where previous studies have reported that married respondents are less likely to experience depressive symptoms[29]. Theoretically, marriage is associated with better social engagement, support, and integration[30], all of which have been linked to better health and well-being[31], including the prevention of depression in old age.

Although the relationship between marriage and depressive symptoms in older adults is well established, the moderating role of marital status in the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms remains underexplored. Previous research suggests that marital status can moderate the relationship between certain factors and health later in life. For example, a study using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study found that unmarried older adults who frequently participated in hobby groups had a stronger association with reduced physical frailty than their married counterparts[32]. Another study of older Ghanaian cohorts found that marital status moderated the association between self-rated health and functional decline, particularly in women. Married women with fair or poor self-rated health showed a decrease in functional decline compared to their unmarried counterparts[33]. However, empirical research on the moderating role of marital status in the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms among older adults, especially in China, is lacking. Based on previous studies, it is necessary to examine the moderating role of marital status in the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms. Clarifying the role of marital status in the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms will help policymakers design more effective and precise interventions to prevent depression in older adults.

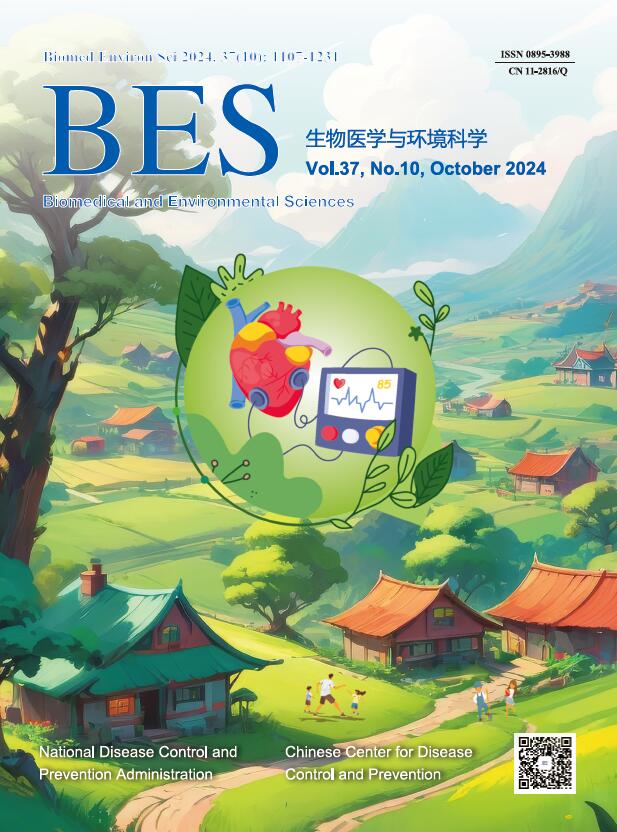

Furthermore, controlling confounding factors in observational studies is crucial, as they can influence the estimated association between social engagement and depressive symptoms, potentially leading to misleading conclusions[34,35]. Current research often overlooks basic variables such as personality traits despite previous studies demonstrating a significant association between personality and depression. For example, a study with a clinical sample of French patients with major depressive episodes found that a depressive episode is strongly associated with a specific personality profile, including Neuroticism, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to Experience and Agreeableness[36]. This oversight necessitates a careful consideration of confounding factors, particularly those related to older adults’ personalities, to accurately estimate the association between social engagement and depressive symptoms. In summary, this study aimed to explore the complex relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms among older adults in China, with a particular focus on the moderating role of marital status. Incorporating the interaction between social engagement and marital status provides a more complex and deeper understanding of the simple bivariate relationships between social engagement and depressive symptoms. Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study.

-

This study uses data from the 2017–2018 wave of the CLHLS, a pivotal survey in aging research that includes a wide array of demographic, social, and health-related variables. Initiated in 1998, the CLHLS was conducted in successive waves approximately every two to three years, covering 23 provinces in China, to ensure a comprehensive representation of the aging population. Occasional variations in the intervals between waves due to funding, logistical challenges, or methodological enhancements reflect the operational dynamics of long-term longitudinal research. The 2017–2018 wave is particularly noteworthy for incorporating advanced measurement scales such as the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for assessing emotional well-being and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) for measuring depressive symptoms. These enhancements have significantly enriched the dataset, enabling more nuanced analyses of the psychological health of older adults and augmenting the relevance of the survey to current aging research. The broad demographic coverage and introduction of these sophisticated measures in the latest wave enhanced the reliability and relevance of the survey for current aging research. The CLHLS’s commitment to data sharing and its established role in the international research community further validate its contribution to the field. The data from the 2017–2018 wave chosen for this study offered the most updated insights into the characteristics of the participants, forming the basis for our analysis. Further information on the CLHLS is available on its official website (https://cpha.duke.edu/index.php/research/chinese-longitudinal-healthy-longevity-survey).

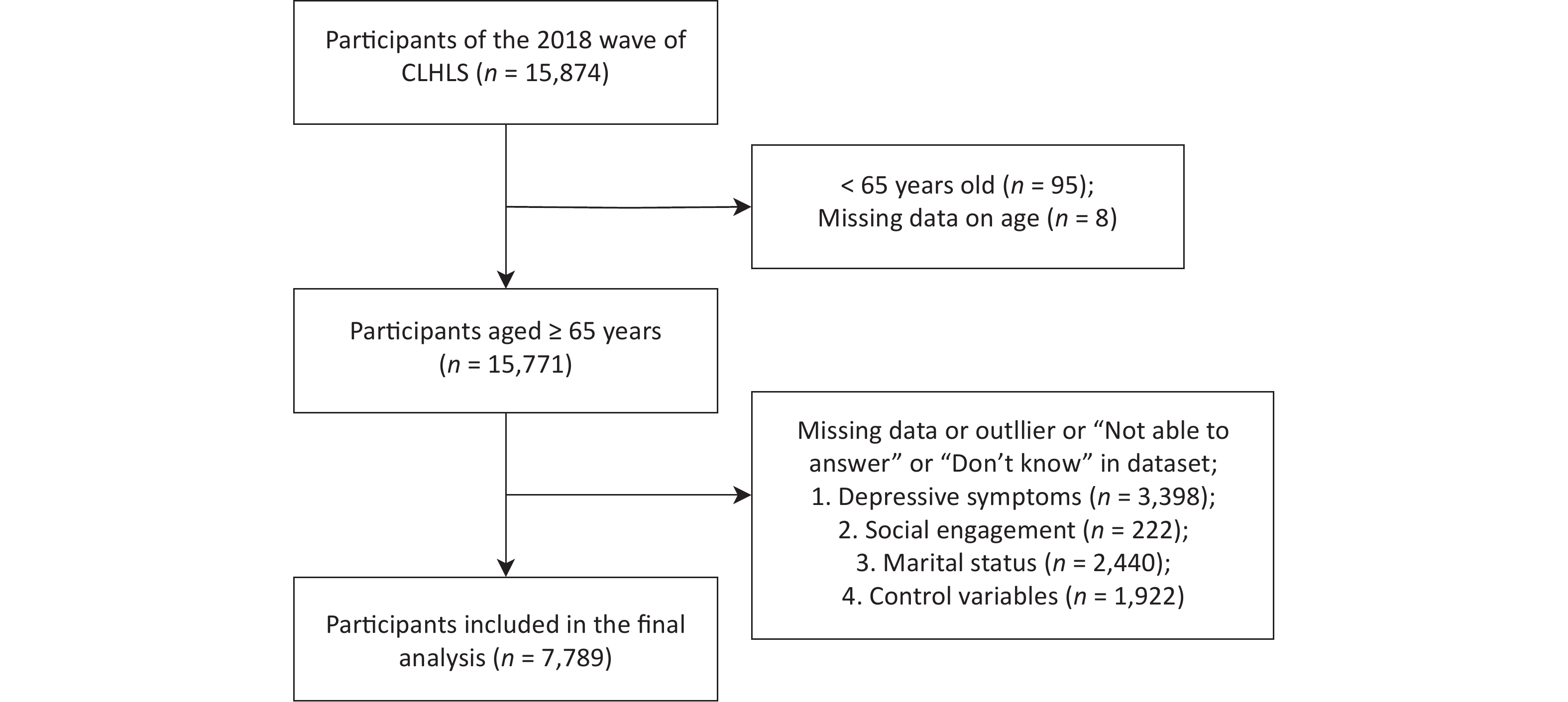

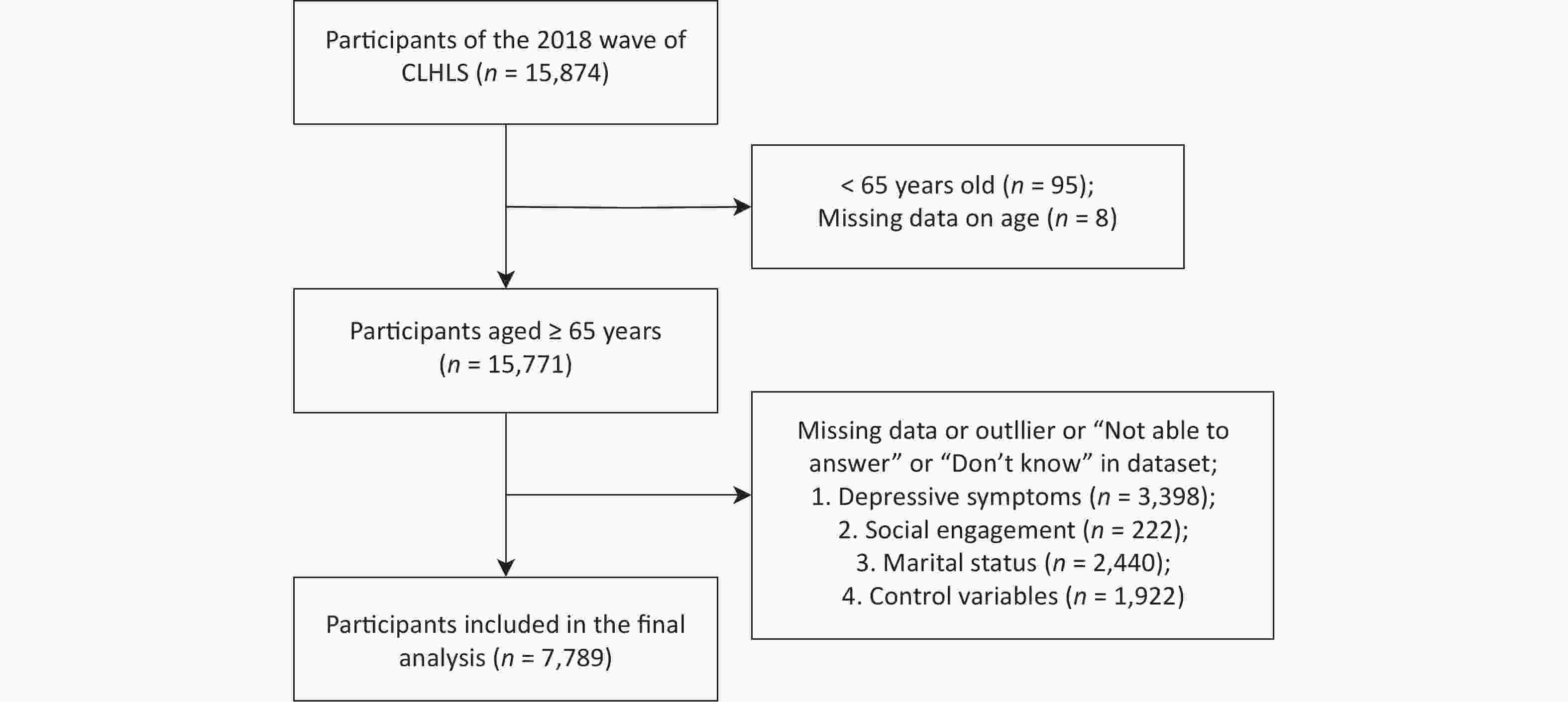

According to the purpose of this study, we formulated the excluded criteria for the study subjects: (1) were aged 64 and younger, (2) replied “Don’t know” and “Not able to answer” in the dataset, (3) had missing information and outlier that do not pass the IQR (Inter-Quartile Rang) test. The final sample size was 7,789 (Figure 2).

-

The depressive symptoms were measured using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10)[37]. This scale is a widely used survey tool to measure depressive symptoms among older Chinese adults with good validity and reliability[38,39]. The scale consists of 10 items, including seven that reflect negative psychological conditions and three that reflect positive psychological conditions. The CES-D-10 scale asks respondents to indicate the frequency of experiencing the following symptoms in the past one or two weeks and assigns a score to each item based on their responses. For items reflecting negative psychological conditions, the scores are as follows: “Always” receives 3 points, “Often” receives 2 points, “Sometimes” receives 1 point, and “Rarely or Never” receives 0 points. For items reflecting positive psychological conditions, the scoring is reversed: “Always” receives 0 points, “Often” receives 1 point, “Sometimes” receives 2 points, and “Rarely or Never” receives 3 points. The total score of the 10 items represented the respondent's CES-D-10 score, ranging from 0 to 30 points. A higher CES-D-10 score indicated a higher level of depressive symptoms. Studies assessing the reliability and validity of the CES-D-10 have shown that it effectively measures depression levels among middle-aged and older adults in China[40]. Cronbach’s α coefficient of the CES-D-10 scale for this study was 0.82.

-

In our study, social engagement was quantified through participation in eight specific leisure activities as defined by the CLHLS. These activities were carefully selected to ensure a comprehensive reflection on older adults’ social engagement based on their relevance and frequency within the target group.

Specifically, the degree of social engagement was assessed by the frequency of participation in the following eight leisure activities: doing household chores, participating in outdoor activities (e.g., Tai Ji, square dancing, visiting friends and relatives, and other outdoor activities), gardening, reading newspapers or books, raising livestock or pets, playing cards or Mahjong, watching television, listening to the radio or and attending organized social activities. The participation frequency for each activity was scored on a five-point scale, ranging from “rarely or never participate” (1 point) to “participate daily” (5 points). The score for outdoor activities was calculated by summing the scores of the four related activities (totaling 4–20 points), whereas the score for organized social activities was directly based on their frequency (ranging from 1–5 points). For activities other than outdoor and organized social activities, scores were aggregated (totaling 6–30 points). The total score for all activities (ranging from 11–55 points) reflected an individual's overall social engagement level, with higher scores indicating greater overall social engagement. This method of measuring social engagement has been validated in previous research[41-45].

Categorizing activities into outdoor activities, organized social activities, and other activities effectively captured the diversity of older adults’ social engagement in daily life. Outdoor activities, which often encompass physical and social interactions, are considered crucial factors influencing the health and well-being of older adults[46,47]. Organized social activities directly mirror the extent of older adults’ participation in social groups and activities, acting as a key indicator of their social networks and support[48]. Activities classified as “other activities”, including doing household chores, gardening, reading newspapers or books, raising livestock or pets, playing cards or Mahjong, watching television or listening to the radio, although possibly involving more personal time, are equally significant components of older adults’ social engagement within cultural and community contexts. For instance, community gardening is not only a personal hobby but often involves interaction and cooperation with family members and neighbors, such as sharing gardening techniques or fostering community interaction and social connections[49]. Therefore, these activities are collectively considered to provide a holistic reflection of the older adults’ social engagement status.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for social engagement in this study was 0.64, indicating that the scoring system has acceptable internal consistency within the range of 0.6 to 0.8, further validating the reliability of this method[50]. Moreover, this evaluation method indirectly considers levels of isolation as lower participation scores may indicate a higher degree of social isolation, a known risk factor for depressive symptoms. Through a comprehensive assessment of participation frequency, we aimed to capture the extent of each individual’s social network and support, which are key elements in alleviating depressive symptoms.

-

In this study, marital status was categorized as “currently married” (coded 1) or “currently unmarried” (coded 0) to examine its impact on the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms among older adults. This binary classification focuses on the overarching influence of marital union, as marriage is associated with a structured support system that can affect social engagement and mental health outcomes. The “currently unmarried” category includes individuals who are widowed, divorced, separated, or have never married, each with distinct social and emotional contexts. This approach allows for a focused exploration of how marital-based social support structures influence older adults’ mental health, providing clarity and manageability for analysis[51,52].

-

In this study, we meticulously selected a comprehensive array of variables to explore how various factors collectively influence depressive symptoms among older adults based on an extensive review of the literature and the synthesis of existing questions within the CLHLS. Our aim was to comprehensively account for the dimensions known to affect depressive symptoms, such as demographic variables, socioeconomic status, and health conditions.

First, the selection of demographic variables, including age (measured continuously) and sex (male = 0, female = 1), was informed by their well-documented strong associations with depressive symptoms among older adults. Additionally, we included socioeconomic variables such as income (categorized as < 100,000 yuan = 0, ≥ 100,000 yuan = 1), hukou (city = 0, rural = 1), school years (measured continuously by years of education), and number of children (measured continuously). These were chosen based on their documented impact on individuals' access to health resources and their capacity to engage in and receive social support, reflecting the broader social determinants of mental health[53].

Moreover, health condition variables, including body mass index (BMI), calculated according to the formula from the National Health Statistics Center, and self-reported health status (assessed on a scale of 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating worse health) were selected to assess the overall health status of older adults from both subjective and objective perspectives. These measures offer insights into the influence of physical conditions on mental well-being, highlighting the intricate interplay between physical health and depressive symptoms[54-56].

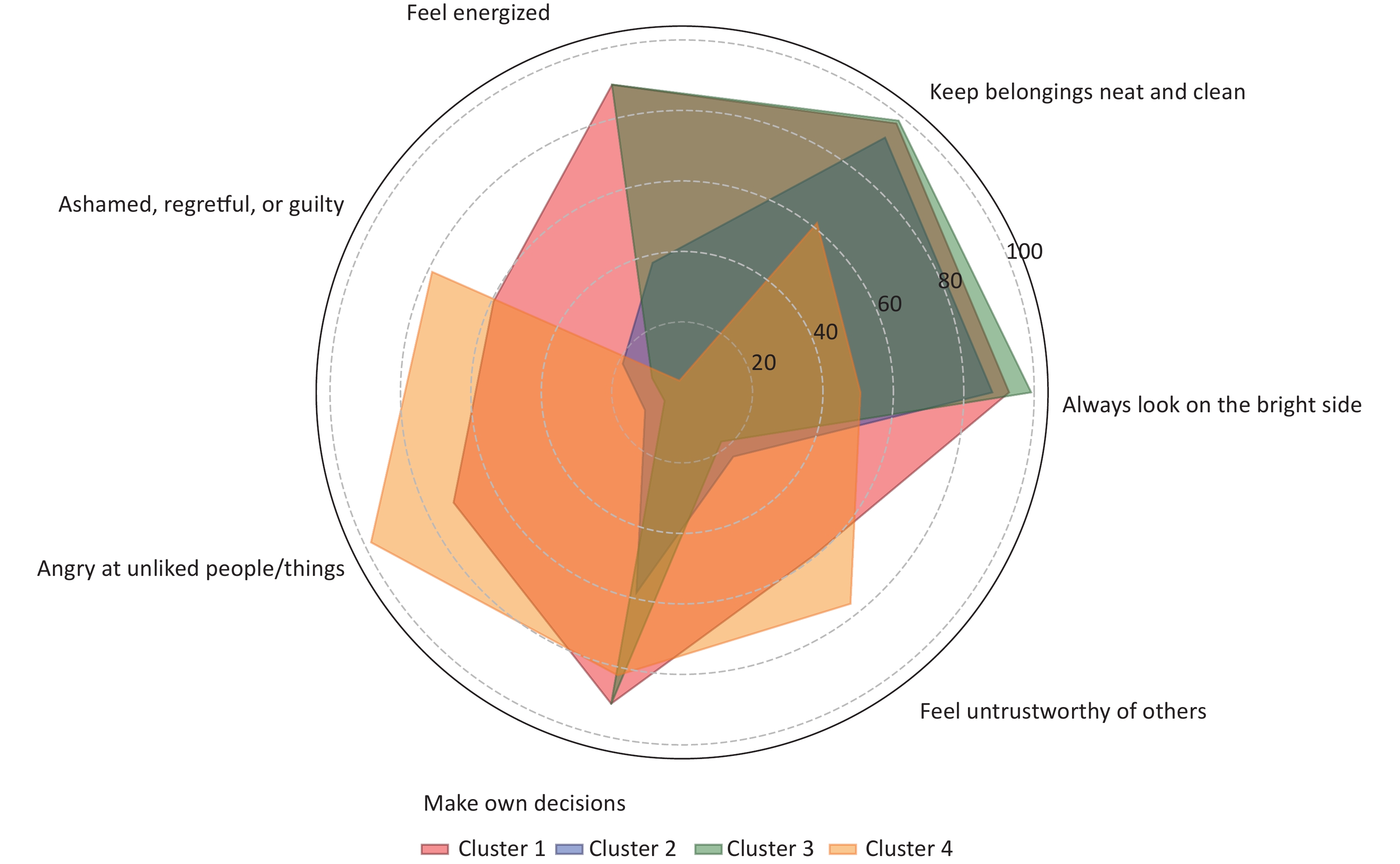

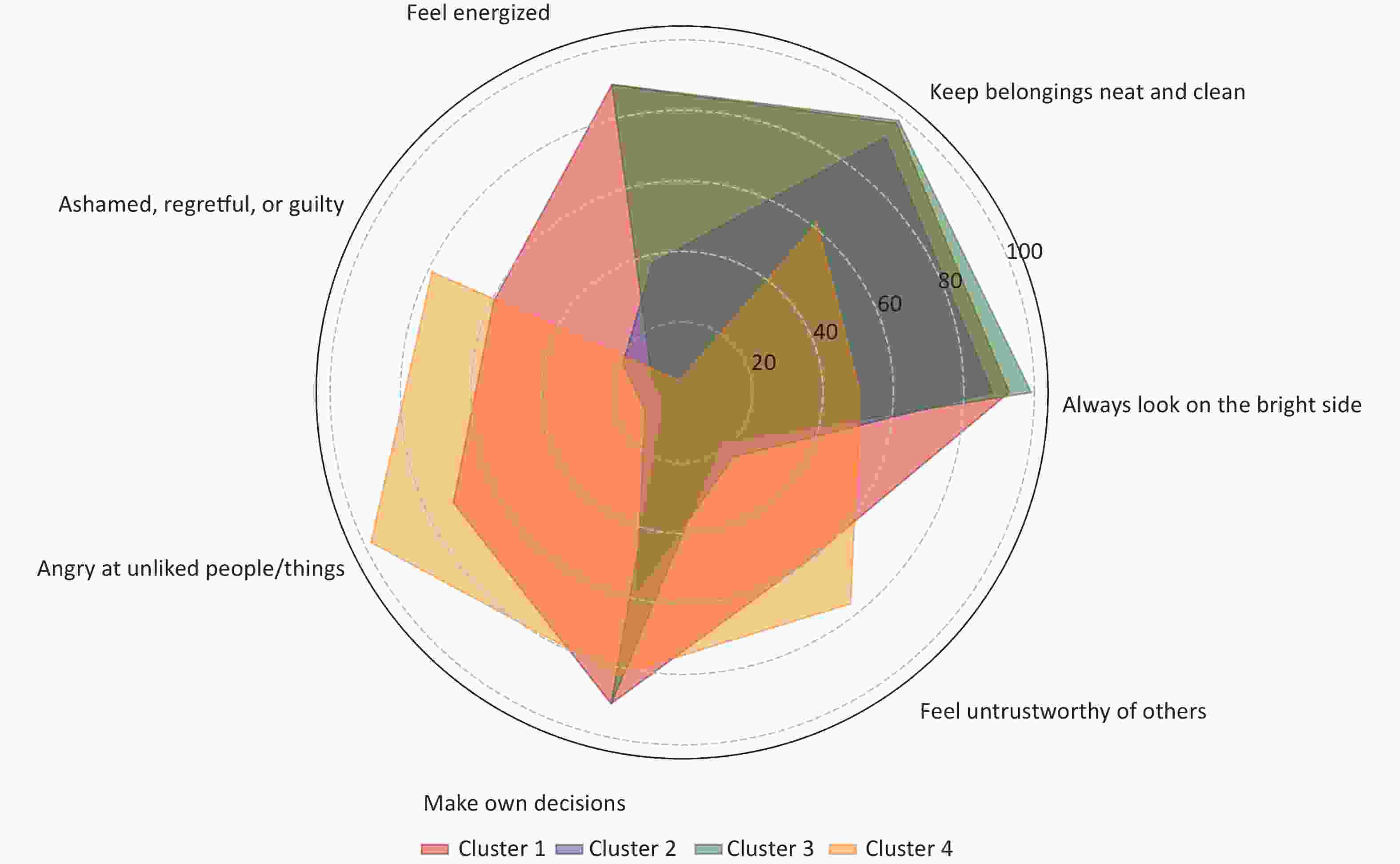

Finally, acknowledging the potential impact of personality on mental health, we incorporated personality traits as a significant research variable. Based on the relevant questions within the CLHLS, personality was assessed using seven continuous questions covering different aspects of attitudes toward life (e.g., “Do you always see the bright side of things?” and “Do you like to keep your things tidy and organized?”) (Table 1). Responses were scaled from 1 to 5, where 1 represented “always” and 5 represented “never.” For the subsequent latent class analysis (LCA), scores from 1 to 3 were uniformly coded as 2, whereas scores of 4 and 5 were coded as 1. This nuanced approach enabled us to consider the multifaceted nature of mental health, acknowledging that individuals’ outlook and behavioral patterns can significantly influence their psychological well-being. This method of measuring personality traits has been validated in previous research[57].

Questions Total Cluster 1 Cluster 2 Cluster 3 Cluster 4 P−value Do you always look at the bright side of things? 96.00% 76.50% 92.70% 99.00% 33.00% < 0.001 Do you like to keep your belongings neat and clean? 97.10% 83.00% 97.30% 98.80% 50.00% < 0.001 Do you feel energized? 82.80% 9.70% 87.90% 87.80% 0.00% < 0.001 Have you been ashamed, regretful, or felt guilty about things you’ve done? 20.90% 17.80% 73.70% 9.00% 82.01% < 0.001 Are you angry at people or things you don’t like around you? 20.00% 12.30% 80.30% 6.60% 100.00% < 0.001 Can you make your own decisions concerning your personal affairs? 87.30% 19.80% 90.80% 91.10% 75.50% < 0.001 Do you feel that people around you are not trustworthy? 27.10% 21.70% 74.80% 16.60% 81.10% < 0.001 Note. Bold font indicates variables with statistically significant differences across clusters as Indicated by chi-square test results (P < 0.001). Clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4 refer to Reflective Moderates, Discerning Assertives, Confident Idealists, and Disenchanted Realists, respectively. Table 1. Distribution of responses to attitudinal questions across groups and Chi-Square test results

-

The statistical analysis was conducted primarily using SPSS 26.0 and R 4.2.1 software, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05.

Initially, the study used LCA to categorize respondents into distinct personality clusters based on their responses to a series of questions on attitudes toward life. The objective was to group individuals based on their responses to specific variables, ensuring that the responses within the same group were as similar as possible, whereas those between different groups were as distinct as possible. Given that the sample size exceeded 1,000, the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used to assess the fit of various models[58], with the model boasting the lowest selected BIC value. This analysis was performed using the poLCA package in R, version 4.2.1. Following LCA[59], significant differences in the distribution of responses to attitudinal questions across personality clusters were analyzed using chi-square tests, after which dummy variables were created, and a preliminary description of all data characteristics was conducted with categorical variables represented by frequency (n) and percentage (%) and continuous variables by mean (x) and standard deviation (s).

Subsequently, a comprehensive evaluation of the correlations between all included variables and depressive symptoms was conducted using Pearson’s and point-biserial correlations (r). Hierarchical linear regression and the PROCESS macro were used to examine the effects of social engagement on depressive symptoms and the moderating role of marital status. In addition, separate modeling analyses were performed for each type of activity variable and their interaction with marital status to isolate their individual effects. All social engagement variables were standardized to address multicollinearity. To further investigate our models, we conducted simple effect analyses of significant interactions to examine how marital status might affect the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms.

-

In our study involving 7,789 participants, we used LCA to categorize respondents into distinct personality clusters based on their responses to questions related to their attitudes toward life. Models ranging from two to five clusters were developed to determine the optimal model based on fit criteria. The BIC values consistently decreased from the two-cluster to the four-cluster model, after which a gradual increase was observed, as detailed in Table 2. Hence, based on the BIC values, the four-cluster solution was identified as the optimal configuration.

Number of Clusters G2 df AIC BIC 2 494.84 112 40915.92 41020.32 3 302.13 104 40739.21 40899.30 4 121.42 96 40574.50 40790.27 5 105.62 88 40574.70 40846.16 Note. G2, deviance statistic; df, residual degrees of freedom; AIC, akaike information criteria; BIC, bayesian information criterion. Table 2. Goodness-of-Fit measures of the four-cluster models

Subsequently, chi-square tests were used to evaluate whether significant differences existed in the responses to various questions among the different groups. The results indicated statistically significant differences across all questions among the clusters (P < 0.001), lending support to the division into four groups, as determined by LCA. These differences suggest that the groups possess unique characteristics in their attitudes toward life. Table 1 presents the actual proportion of responses to each question within each group, and Figure 3 illustrates the model-predicted probabilities of responses to each question across groups.

Figure 3. Conditional probabilities of the seven consecutive questions about life attitude among four clusters. Legend: Clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4 refer to Discerning Assertives, Reflective Moderates, Confident Idealists, and Disenchanted Realists, respectively.

To highlight the principal differences among the clusters and provide more accurate interpretations, we designated the four clusters as Reflective Moderates, Discerning Assertives, Confident Idealists, and Disenchanted Realists.

-

This cluster combines optimism with a thoughtful awareness of emotional challenges. With 76.50% viewing things positively and 83.00% valuing neatness, they prioritize a harmonious life. However, low figures—9.70% feeling energized and 17.80% experiencing guilt—indicate deep self-reflection. Their struggles with decision-making (19.80%) further emphasize their cautious, reflective approach to navigating life's complexities.

-

This cluster showed high percentages in autonomy (90.80%), tidiness (97.30%), and a positive attitude (92.70%) but a significant proportion of angry reactions to disliked situations or individuals (80.30%). This suggests a strong self-awareness and a sense of order, with pronounced emotional reactions, while maintaining a high level of optimism toward life.

-

This group had the highest percentages in almost all positive dimensions, such as always seeing the bright side of things (99.00%), feeling energetic (87.80%), and having autonomy in personal affairs (91.10%). Notably, only 9.00% of members report experiencing feelings of shame or regret about their actions, which reflects their overall confidence and self-acceptance. Moreover, they had the lowest proportions of anger toward disliked situations or individuals and distrust, indicating that this group had a positive view of their environment and interpersonal relationships, exhibiting a distinctly positive attitude toward life.

-

This cluster had the lowest percentages in optimism (33.00%) and vitality (0.00%), as well as lower scores in tidiness (50.00%), indicating a general disengagement or dissatisfaction with life. Moreover, they had the highest proportion of anger toward disliked situations or individuals (100.00%) and distrust (81.10%), reflecting this group’s struggle with negative emotions and a pessimistic view of their environment and interpersonal relationships, exhibiting a distinctly negative attitude toward life.

In summary, the clusters can be ranked from the most positive to the most negative in terms of their outlook on life and emotional responses: Confident Idealists, Discerning Assertives, Reflective Moderates, and Disenchanted Realists.

-

The demographic profiles of the study participants are shown in Table 3. The analysis encompassed 7,789 respondents (mean age: 82.53 [s = 11.20] years). Sex distribution was 54.0% female and 46.0% male respondents. A substantial majority (69.1%) resided in rural areas, with the remaining 30.9% living in the city. In terms of economic status, 79.3 bulk of the cohort reported an annual income below 100,000 yuan, whereas 20.7% exceeded this threshold. More than half of the participants (52.8%) were currently unmarried, including those who were widowed, divorced, or never married, whereas the remaining 47.2% were currently married. The educational background revealed an average of 3.71 (s = 4.11) years of schooling. BMI calculations yielded an average of 22.49 (s = 3.77), with most participants within the normal weight range. Self-reported health was rated at an average of 2.52 (s = 0.89), indicating that the participants generally perceived their health as moderate. The average score for depressive symptoms among participants, measured using the CES-D scale, was 10.77 (s = 5.00). Regarding social engagement, the assessment revealed varied levels of activity involvement: the average score for engagement was 22.88 (s = 7.31); for organized social activities, it was 1.36 (s = 0.94); for outdoor activities, the average was 7.39 (s = 3.00); and for other activities, participants scored an average of 14.13 (s = 5.07). Based on personality characteristics, participants were divided into four clusters: Reflective Moderates (4.9%), Discerning Assertives (16.1%), Confident Idealists (77.6%), and Disenchanted Realists (1.4%). This classification indicates that most participants were Confident Idealists, displaying a positive and optimistic outlook on life.

Variables Category Frequency (n) Percentage (%) / x ± s Coefficient of correlation Agea 7,789 82.53 ± 11.20 0.086** Sexb Male 3,583 46.00 0.100** Female 4,206 54.00 Hukoub City 2,409 30.90 0.070** Rural 5,380 69.10 Incomeb < 100,000 yuan 6,177 79.30 –0.075** ≥ 100,000 yuan 1,612 20.70 Marital Statusb Currently Married 4,110 52.80 –0.116** Currently Unmarried 3,679 47.20 Personality Clustersb Reflective Moderates 383 4.90 0.140** Discerning Assertives 1,254 16.10 0.221** Confident Idealists 6,046 77.60 –0.325** Disenchanted Realists 106 1.40 0.208** School yearsa 7,789 3.71 ± 4.11 –0.132** Number of Childrena 7,789 3.76 ± 1.89 0.050** BMIa 7,789 22.49 ± 3.77 –0.120** Self-Reported Healtha 7,789 2.52 ± 0.89 0.421** Social Engagementa 7,789 22.88 ± 7.31 –0.190** Organized Social Activitiesa 7,789 1.36 ± 0.94 –0.067** Outdoor Activitiesa 7,789 7.39 ± 3.00 –0.116** Other Activitiesa 7,789 14.13 ± 5.07 –0.192** Note. aPearson method; bPoint-biserial correlation method; **Significantly correlated at the 0.01 level (bilateral); BMI, body mass index; x, Mean; s, Standard deviation. Table 3. Summary of the social demographic characteristics of the study participants (n = 7,789) and their correlations with depressive symptoms

-

Prior to conducting the hierarchical regression analysis, we performed a correlation analysis on a sample of 7,789 participants to explore the relationships between sociodemographic characteristics and depressive symptoms. The analysis results indicated that all variables selected for this study were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Additionally, for personality groups identified through LCA, Reflective Moderates, Discerning Assertives, Confident Idealists, and Disenchanted Realists also showed significant correlations with depressive symptoms. These findings supported the selection of variables for the hierarchical regression analysis by demonstrating significant associations between sociodemographic characteristics, personality clusters, and depressive symptoms. This confirmation of relevant associations ensures that our regression model is based on empirically supported variables.

-

We initiated a hierarchical linear regression analysis to examine the effect of social engagement on depressive symptoms among older participants. The overall fit of the regression models across all iterations was statistically significant (P < 0.001), and detailed results are presented in Table 4. The adjusted R² values were 0.274 (Model 1), 0.280 (Model 2), 0.283 (Model 3), and 0.284 (Model 4). Model 1, the baseline model, incorporated a series of control variables. Significant predictors of depressive symptoms included Age, Sex, Income, Clusters (Reflective Moderates, Discerning Assertives, Confident Idealists, Disenchanted Realists), School Years, BMI, and Self-Reported Health (P < 0.05). Model 2 introduced social engagement as a predictor and identified a significant linear relationship, where an increase in social engagement was correlated with a decrease in depressive symptoms (t = −7.932, P < 0.001, B = −0.463, 95% CI: −0.578 to −0.349). Model 3 added marital status as a predictor, revealing that being currently married was associated with fewer depressive symptoms (t = −6.368, P < 0.001, B = −0.750, 95% CI: −0.980 to −0.519). Model 4 included an interaction term between social engagement and marital status, indicating that the effect of social engagement on depressive symptoms was moderated by marital status (t = −2.092, P = 0.037, B = −0.217, 95% CI: −0.420 to −0.014).

Predictors Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 β β β β Age 0.062*** 0.022 –0.013 –0.009 Sex Male Ref Female 0.055*** 0.057*** 0.041*** 0.044*** Hukou City Ref Rural 0.022 0.016 0.018 0.018 Income < 100,000 yuan Ref ≥ 100,000 yuan −0.028** −0.024* −0.024* −0.023* Personality Cluster Disenchanted Realists Ref Reflective Moderates −0.232*** −0.232*** −0.234*** −0.233*** Discerning Assertives −0.338*** −0.327*** −0.329*** −0.327*** Confident Idealists −0.625*** −0.612*** −0.615*** −0.613*** School Years −0.070*** −0.051*** −0.047*** −0.046*** Number of Children −0.016 −0.014 −0.014 −0.016 BMI −0.061*** −0.059*** −0.058*** −0.059*** Self-Reported Health 0.354*** 0.345*** 0.346*** 0.346*** Social Engagement −0.093*** −0.090*** −0.069*** Marital Status Currently Married Ref Currently Unmarried −0.075*** −0.072*** Social Engagement × Marital Status −0.028* Adjusted R2 0.274 0.280 0.283 0.284 Overall Model Significance F (11, 7,777) = 268.319*** F (12, 7,776) = 253.160*** F (13, 7,775) = 237.994*** F (14, 7,774) = 221.403*** Note. β, standardized coefficient. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001. BMI, body mass index. Table 4. Summary of regression analysis for the effects of social engagement, marital status, and their interaction on depressive symptoms

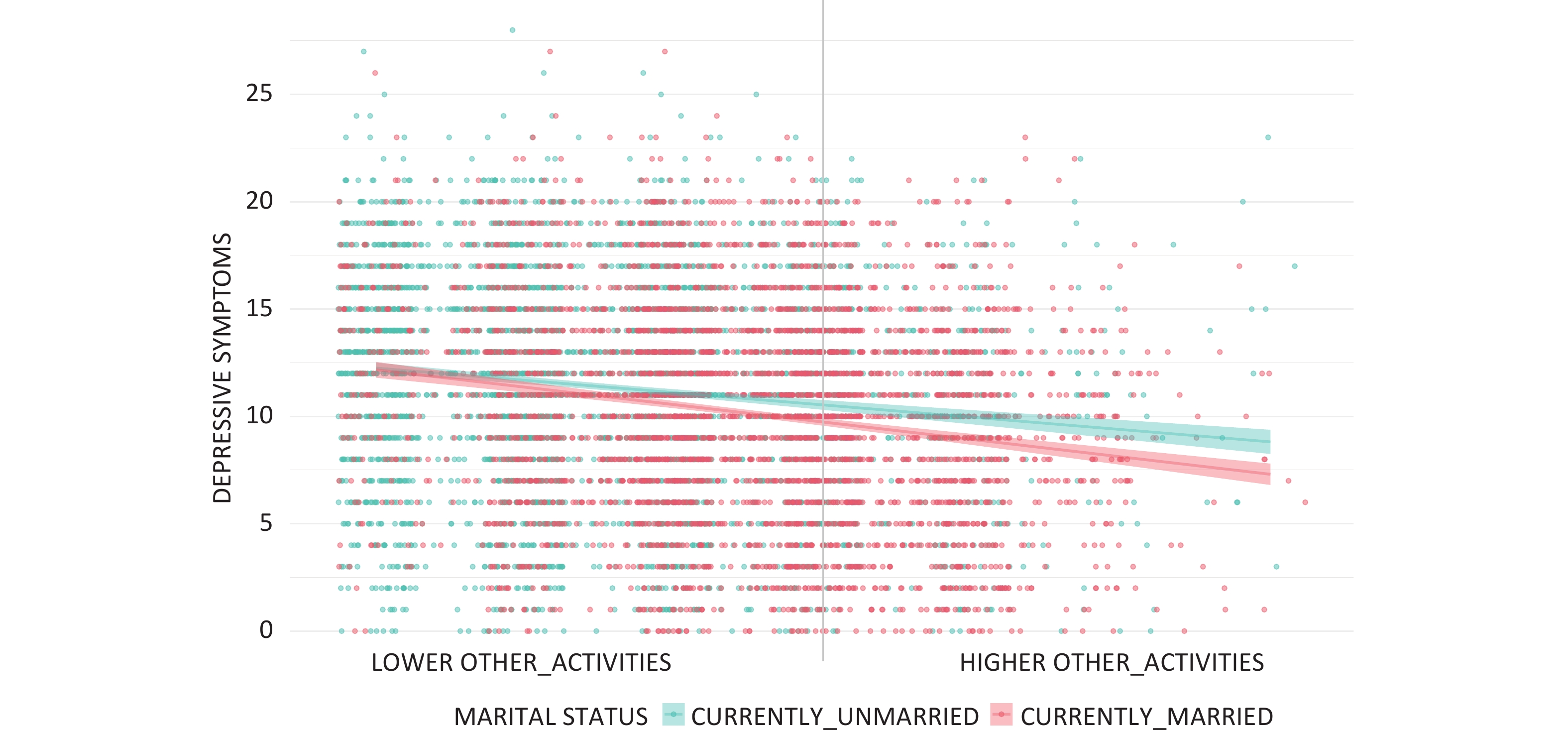

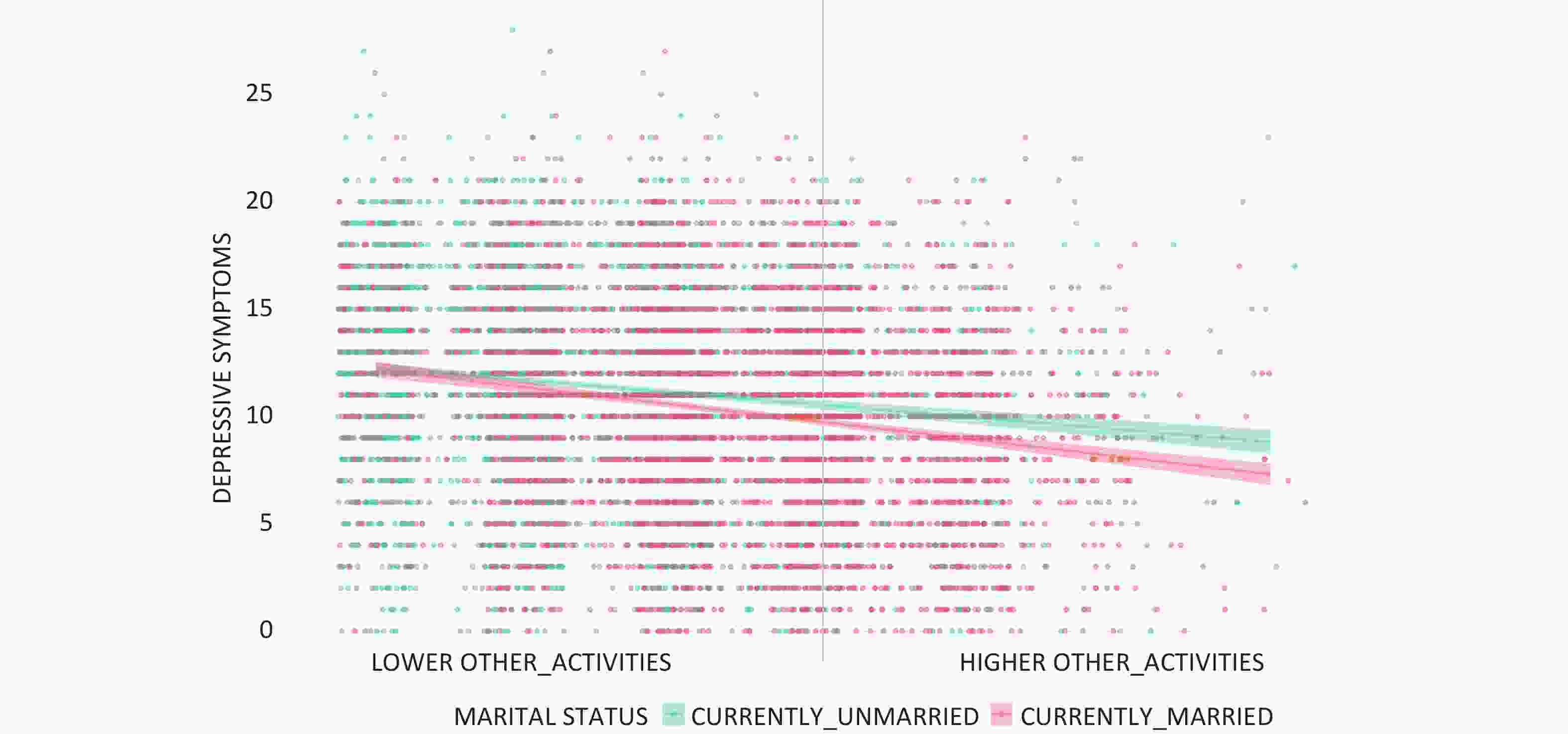

Subsequent analyses introduced three categories of social engagement activities (organized social activities, outdoor activities, and other activities), marital status, and their interactions with specific social activity types as variables in Models 5, 6, and 7, based on Model 1. The detailed results are presented in Table 5. The adjusted R² values for these models were 0.278, 0.279, and 0.285, respectively. Notably, Model 7, which included interactions between other activities and marital status, exhibited the highest adjusted R² value among all the established models. Specifically, engagement in other activities was associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms (t = −5.174, P < 0.001, B = −0.398, 95% CI: −0.549 to −0.247), and the interaction between marital status and other activities significantly influenced the level of depressive symptoms (t = −2.180, P = 0.029, B = −0.228, 95% CI: −0.432 to −0.023).

Predictors Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 β β β Age 0.023 0.016 −0.012 Sex Male Ref Female 0.040*** 0.040*** 0.043*** Hukou City Ref Rural 0.020 0.022 0.020 Income < 100,000 yuan Ref ≥ 100,000 yuan −0.026** −0.026* −0.023* Personality Clusters Disenchanted Realists Ref Reflective Moderates −0.235*** −0.234*** −0.231*** Discerning Assertives −0.341*** −0.337*** −0.325*** Confident Idealists −0.629*** −0.624*** −0.610*** School Years −0.062*** −0.062*** −0.044*** Number of Children −0.018 −0.016 −0.017 BMI −0.061*** −0.060*** −0.059*** Self-Reported Health 0.354*** 0.352*** 0.347*** Marital Status Currently Married Ref Currently Unmarried −0.078*** −0.078*** −0.068*** Organized Social Activities 0.000 Organized Social Activities × Marital Status −0.024 Outdoor Activities −0.025 Outdoor Activities × Marital Status −0.007 Other Activities −0.080*** Other Activities × Marital Status −0.030* Adjusted R2 0.278 0.279 0.285 Overall Model Significance F (14, 7,774) = 215.682*** F (14, 7,774) = 215.960*** F (14, 7,774) = 223.112*** Note. β, standardized coefficient. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001. BMI, body mass index. Table 5. Summary of regression analysis for the effects of organized social activities, outdoor activities, and other activities on depressive symptoms

In our regression models, Reflective Moderates, Discerning Assertives, and Confident Idealists showed lower depressive symptoms than Disenchanted Realists, with Confident Idealists having the least association with depressive symptoms. Moreover, to further understand the significant impact of this variable on depressive symptoms among older adults, we removed these four personality-related variables from the final regression Model 7. The results showed a significant decrease in the explanatory power of our model, with the R-squared value dropping from 0.285 to 0.153. These personality-related variables contribute significantly to explaining depressive symptoms in older adults.

Post-hoc simple effects tests indicated that the impact of social engagement and other activities on depressive symptoms varied depending on marital status. For currently married older adults, the degree of social engagement explained 27.4% of the variance in depressive symptoms [F (12,3666) = 116.625, P < 0.001], whereas other activities explained 27.6% of the variance [F (12,3666) = 117.722, P < 0.001]. For currently unmarried older adults, social engagement explained 28.0% of the variance in depressive symptoms [F (12,4097) = 133.955, P < 0.001], and other activities explained 28.1% of the variance [F (12,4097) = 134.789, P < 0.001].

Additionally, among currently married older adults, an increase of one point in social engagement was associated with a 0.535-point decrease in depressive symptoms (95% CI: –0.698 to –0.372, t = –6.433, P < 0.001). A similar increase in other activities was linked to a 0.587-point decrease in depressive symptoms (95% CI: –0.748 to –0.426, t = –7.143, P < 0.001). In contrast, for currently unmarried older adults, a one-point increase in social engagement corresponded with a 0.387-point decrease in depressive symptoms (95% CI: –0.548 to –0.226, t = –4.704, P < 0.001) and a one-point increase in other activities was associated with a 0.450-point reduction in depressive symptoms (95% CI: –0.613 to –0.287, t = –5.418, P < 0.001). The moderating effect of marital status on the relationship between other activities and depressive symptoms is shown in Figure 4.

-

Based on a sample of 7,789 older Chinese adults, this study aimed to investigate the relationships between social engagement, marital status, and depressive symptoms. The results revealed a significant negative correlation between social engagement and marital status with depressive symptoms and marital status moderating the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the impact of marital status on depressive symptoms varies across different types of social activities.

Using LCA, we identified four personality groups, with individuals categorized as Confident Idealists reporting fewer depressive symptoms. This observation suggests a potential association between a positive outlook, such as optimism, and reduced depressive symptoms. This finding aligns with previous studies, including research using the CLHLS, which found that over half of the older adult participants were categorized as optimistic[60]. Similarly, a study utilizing a national dataset from the Chinese General Social Survey demonstrated that the average optimism score was 3.86 (s = 0.85) on a 1–5 scale, further supporting the link between optimism and subjective well-being[61].

Through hierarchical linear regression analysis, our study indicated that compared to married older adults engaged in organized or outdoor activities, those participating in other types of activities, such as doing household chores, gardening, or reading newspapers or books, might experience greater psychological benefits, as evidenced by their association with lower depressive symptoms. This observation might be explained by the principles of positive psychology, which suggest that optimists tend to be more resilient when facing life challenges, thereby maintaining a more positive emotional state[62]. Additionally, a significant association was found between higher levels of social engagement and milder depressive symptoms, suggesting a potentially beneficial link that merits further investigation through longitudinal studies. This finding aligns with prevailing trends in the literature, emphasizing the crucial role of social engagement in enhancing the mental health of older adults. Specifically, active participation in social activities can help mitigate the psychological impacts experienced by older adults during transitions in social roles, assist them in redefining their self-identity, and adapt to new roles in society, thereby contributing to the maintenance of a positive outlook on life[63,64]. Our results support the Successful Aging and Activity theories, proposing that older adults can enhance their physical and mental health levels by actively engaging in social activities, which is essential for achieving positive and successful aging[65,66].

Previous research has consistently shown that marital status is an independent factor that influences depressive symptoms in older adults. Our findings corroborate these academic insights, demonstrating not only a direct association between marital status and depressive symptoms but also its moderating role in the relationship between social engagement and depressive symptoms. This moderating effect suggests that marital status can amplify the beneficial effects of social engagement on alleviating depressive symptoms. Specifically, we observed that compared to married older adults who participate in organized social activities or outdoor activities, those who engage more in other activities, such as doing household chores, gardening, and watching television, tend to report greater psychological benefits. This phenomenon could be attributed to the additional personal time these activities afford, allowing for deeper emotional support from spouses, which enhances the positive impact of social interaction and activity participation[67,68]. This interpretation aligns with findings from international research, including a study conducted in Australia that revealed that spousal involvement in community activities has a notably positive impact on partner health, particularly among older men[69].

Although this study provides valuable insights into the associations between social engagement, marital status, and depressive symptoms among older Chinese adults, several limitations must be acknowledged and addressed in future research. First, the use of broad categorizations for the types of activities limited our ability to identify which activities most significantly affected depressive symptoms. Future studies should adopt a more detailed categorization or employ statistical methods, such as cluster analysis, to discern the patterns of activity that most strongly correlate with mental health benefits. Second, our approach to measuring social isolation relied solely on the frequency and variety of social interactions, which may not fully capture the multifaceted nature of the isolation experienced by older adults. Future research should include both qualitative and quantitative measures, such as social network analyses and detailed daily diaries, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of social isolation. Additionally, the binary classification of marital status (“currently married” and “currently unmarried”) simplified the complex effects of different marital conditions on depressive symptoms. Subsequent studies should explore these effects using a multi-category classification system and consider longitudinal designs to understand how changes in marital status over time affect mental health. Another significant limitation is the reliance on self-reported data, which is susceptible to biases such as social desirability and recall bias. To enhance the reliability of data, future research should incorporate objective measures such as behavioral observations and physiological assessments. The integration of wearable technology for monitoring real-time physiological responses and activity levels during social interactions can provide objective and precise data. Finally, the cross-sectional design constrained our ability to establish causal relationships between the variables examined. Longitudinal studies are crucial to determine the directionality of these associations and confirm whether changes in social engagement or marital status lead to changes in depressive symptoms. Addressing these limitations in future research will not only strengthen the findings but also enhance our understanding of how to effectively support the mental health of older adults through targeted social engagement and support systems tailored to their marital status.

-

This study demonstrates a significant relationship between social engagement, marital status, and depressive symptoms among older Chinese adults. This confirms that marital status moderates the impact of social engagement on depressive symptoms, with married older adults involved in other activities such as doing household chores, gardening, reading newspapers or books, raising livestock or pets, playing cards or Mahjong, and watching television or listening to the radio experiencing fewer depressive symptoms. These findings imply that the specific types of activities engaged in by married older adults can influence the extent of their depressive symptoms, possibly due to the support and companionship offered by their spouses. While our results are promising, they highlight the need for further research to explore how different types of social engagement and marital status affect mental health in older adults. Future studies using longitudinal designs could provide deeper insights into these relationships, helping to formulate targeted interventions that can enhance mental health outcomes for this demographic group.

Marital Status as a Moderator: Exploring the Relationship between Social Engagement and Depressive Symptoms in China’s Older Adult Population

doi: 10.3967/bes2024.134

- Received Date: 2023-11-10

- Accepted Date: 2024-07-08

-

Key words:

- Social engagement /

- Depressive symptoms /

- Marital status /

- Moderator /

- Older adults

Abstract:

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

| Citation: | Jianlun Wu, Yaping Ye, Man Zhang, Ruichen Cong, Yitao Chen, Pengfei Yu, Qing Guo. Marital Status as a Moderator: Exploring the Relationship between Social Engagement and Depressive Symptoms in China’s Older Adult Population[J]. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences, 2024, 37(10): 1142-1157. doi: 10.3967/bes2024.134 |

Quick Links

Quick Links

DownLoad:

DownLoad: