-

Lung cancer is one of the leading causes of death, with long-term patient suffering, a heavy disease burden, and high costs among the Chinese population[1]. As patients with lung cancer are frequently hospitalized, caregivers play an important role in their survival[2]. Among caregivers, most are informal caregivers (ICs). Generally, ICs are individuals who provide unpaid assistance to older or dependent people and have a social connection with them, including a spouse, parent, child, other relative, neighbor, friend, or someone who is not a blood relative[3]. Previous studies indicated that cancer is one of the top five diseases requiring informal care[4]. ICs of patients with cancer face tremendous physical and psychological stress, duties, and responsibilities[5].

Identifying factors that would influence caregivers of patients with lung cancer is crucial for improving the patients’ survival time and reducing the disease and economic burden on society as a whole[6]. However, to date, evidence regarding the burden experienced by ICs of patients with lung cancer in China is lacking. Owing to the growing burden faced by ICs, early prevention and control of ICs’ burden has become a crucial topic. Few studies on the factors influencing IC burden have been conducted in China[7,8].

Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify the specific factors that strongly influence the ICs of hospitalized lung cancer patients to improve their health condition, provide effective interventions, and assist them to better support patients with lung cancer.

-

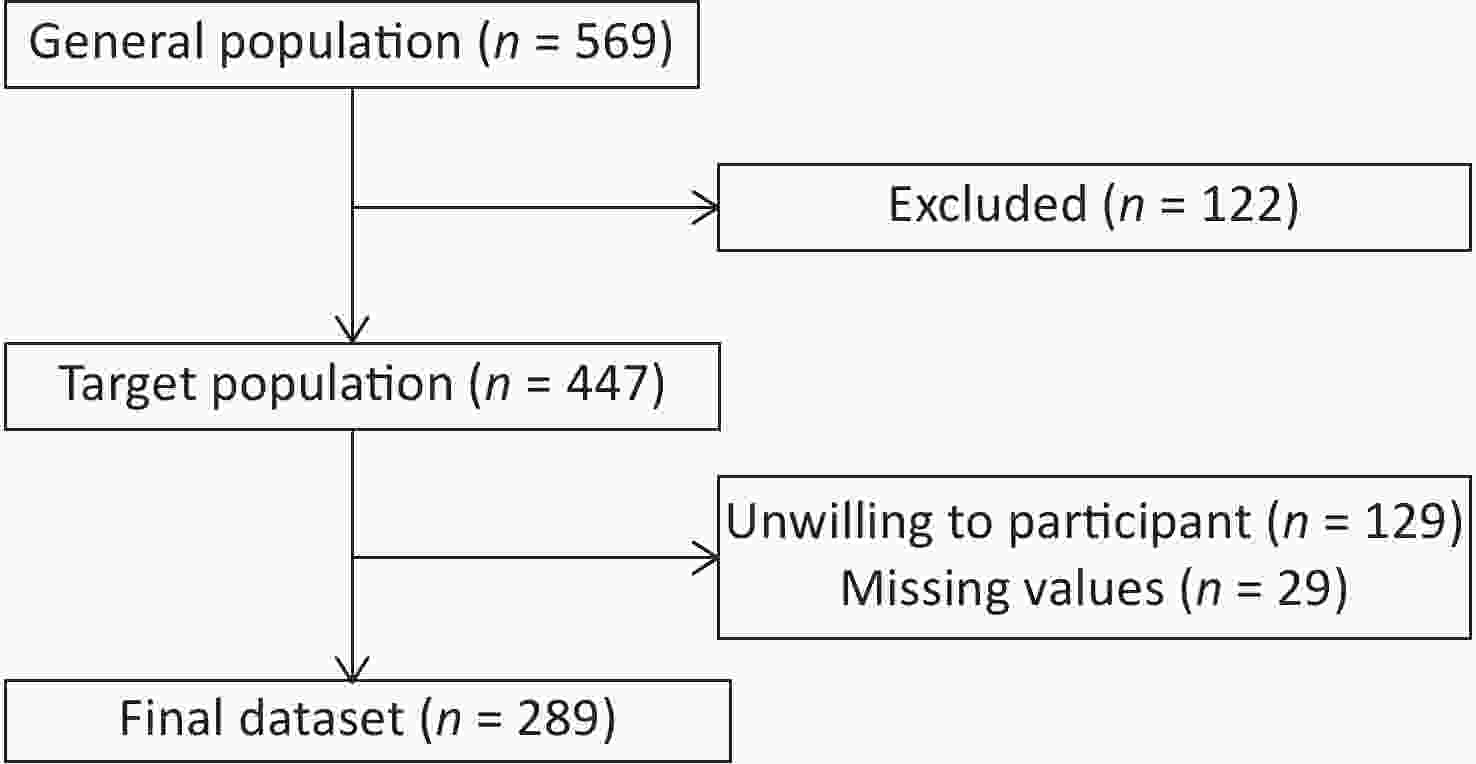

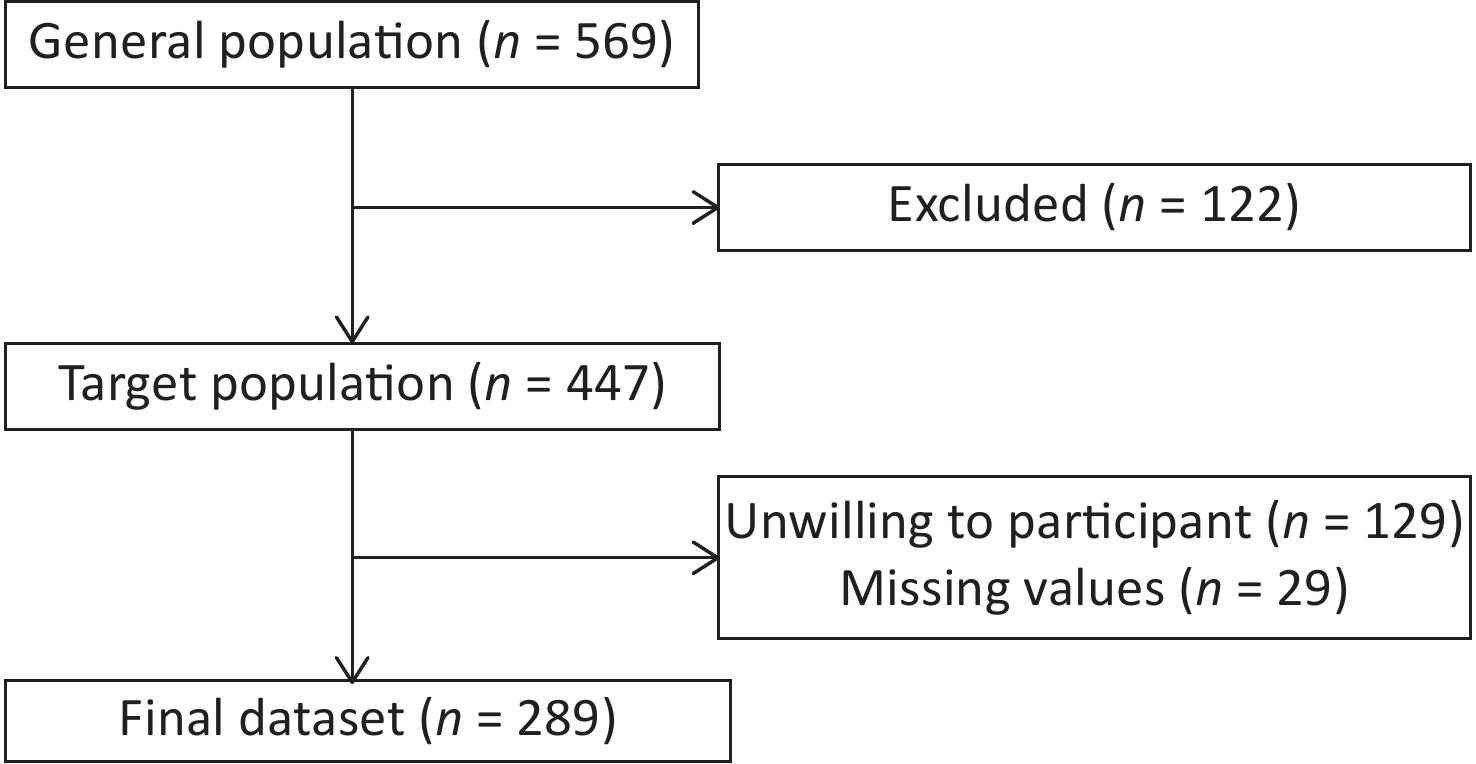

A cross-sectional survey was used to facilitate sampling. Patients with lung cancer were located through medical record system queries and ICs of hospitalized patients with lung cancer in the inpatient ward of the Department of Oncology, Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Hospital, between December 31, 2020 and December 31, 2021, were selected for the questionnaire survey.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) provided written informed consent; (2) cared for patients with cancer diagnosis confirmed by pathology or cellular testing; (3) cared for patients during hospitalization; and (4) were the patients’ partners, parents, children, or friends.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) had an employment relationship with patients with cancer; (2) were aged < 18 years; (3) did not wish to participate in the survey; (4) could not understand the contents of the survey; or (5) did not complete the questionnaire.

Diagnostic criteria for lung cancer[9]: lung cancer diagnosis was based on pathological diagnostic criteria. A confirmed diagnosis of lung cancer should not be made without clear pathological findings; at least the biopsy site should be selected, and a sufficient amount of tissue should be obtained for microscopic examination. Notably, a large number of specimens are required for auxiliary immunohistochemistry and genetic analyses.

-

Demographic information included the patient’s household members, cancer type, gender, age, Activities of Daily Living (ADL) score, patient’s time of cancer diagnosis, IC’s relationship with patients, marital status, patient’s gender, patient’s age, education level, employment status, smoking and drinking status, underlying health problems, and economic status.

Caregiving status included whether the ICs provided full-time care, lived with the patient, duration of caregiving, number of caregiving hours per day, medical expenses of caregiving, and occurrence of acute events during caregiving.

The Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADLS) is the standardized scale used for evaluating cancer patients’ physical function. It is divided into the Basic Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADLS). The BADLS comprises six items: eating, bathing, ambulating, dressing, getting in and out of bed, and toileting. The IADLS comprises eight items: managing finances, making phone calls, housekeeping, shopping, preparing meals, managing transportation, managing medication, and doing laundry. Scoring was based on domestic and international scoring criteria[10]. Participants were scored from 0 to 3 points depending on whether they were completely independent, needed help, had some difficulty, or were completely dependent, respectively. Higher scores indicate a lower ability to perform daily living activities.

-

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)[11] was used to assess sleep quality in ICs of patients with cancer. The ISI consists of seven items, with five options for each item, and scores range from 0 to 4. The scores of the seven items were tallied, with higher total scores indicating more severe insomnia in ICs of patients with cancer. The participants were categorized into four groups based on their total score, with 0–7 indicating no insomnia, 8–14 indicating mild insomnia, 15–21 indicating moderate insomnia, and 22–28 indicating severe insomnia; the scale was suitable for evaluating the participant’s sleep situation for the preceding two weeks[12]. The Chinese version of the ISI has good psychometric properties and can be used as a screening tool for insomnia and as an assessment tool for determining its severity[13].

-

The on-site survey was conducted by four uniformly trained investigators and data were collected as responses to electronic questionnaires. For those who were unable to respond independently (e.g., older adults and individuals with poor vision), the investigator read each sentence and recorded the participants’ responses. Consent was obtained from all ICs before completing the surveys. The investigators had clinical backgrounds and strong communication skills and adopted standardized survey procedures and administration of questionnaire content to ensure survey quality.

-

Electronic questionnaires were administered and the data were double-checked by two researchers. Descriptive statistics and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 23.0; license number: 6b4543b2xxxxf3c69a68). The quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s) or median (M) and interquartile range (IQR), whereas the qualitative data were expressed as percentages. A chi-squared test was performed for comparative analysis of the qualitative data. If the expected value was less than five and greater than one, a continuity-corrected chi-squared test was performed; if the expected value was less than one, Fisher’s exact probability test was performed. The Mann–Whitney U test, independent samples t-test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for the comparative analysis of the quantitative data. If the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not met, corrected one-way ANOVA (Welch’s ANOVA) was performed. Regarding pairwise comparisons of continuous variables after the ANOVA, the Tukey–Kramer test was used if the variances were equal, whereas the Games–Howell test was used if the variances were unequal.

When exploring the factors influencing the burdens faced by ICs of patients with lung cancer, the full model approach was employed for multivariate linear regression and logistic regression, and multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). When performing the multivariate linear regression, a scatter plot was used to determine the linear relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The independence between variables was determined based on expertise. The normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed using residual plots. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the test of parallel lines was performed for ordinal dependent variables. If the test was not satisfied, multinomial variables were used[9]. If certain ordinal or nominal categories contained too few samples, they were combined according to the nature of the dependent variable, and binomial logistic regression analysis was performed.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS software. R software (v4.1.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and R Studio (v1.4.1103, Integrated Development for R, Boston, MA, USA) were used to plot the nomogram for ICs’ burden.

-

A total of 289 ICs of patients with lung cancer were included in the final analysis, of whom 67 reported insomnia (Figure 1). Their ages ranged from 20 to 85 years, and female ICs outnumbered male ICs (58.8% vs. 41.2%, respectively). Of the ICs, 91.0% were married and 46.7% had an undergraduate degree or above. Most ICs were children or spouses, with proportions of 40.8% and 48.8%, respectively. Regarding employment status, 39.8% were full-time workers and 37.4% were retired. The percentages of ICs who smoked or consumed alcohol were 30.4% and 27.7%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Basic characteristics of lung cancer patients’ ICs

Variables Both

(n = 289)Male

(n = 119)Female

(n = 170)T / χ2 / Z P value Insomnia

(n = 67)Non-insomnia

(n = 222)T / χ2 / Z P value Age, years, x ± s 49.44 ± 12.52 47.16 ± 12.31 51.04 ± 12.46 2.615 0.009 52.96 ± 12.66 48.38 ± 12.31 −2.649 0.009 BADLs (P25, P75) 0 (0, 2.5) 0 (0, 3) 0.5 (0, 2.25) −2.133 0.033 1 (0, 4) 0 (0, 2) −3.029 0.003 IADLs (P25, P75) 2 (0, 7) 2 (0, 8) 3 (0,7) −0.634 0.526 4 (0, 10) 2 (0, 6) −2.552 0.012 Years diagnosed with Cancer

(P25, P75)2 (2, 2) 2 (1, 2) 2 (2,2.25) −1.694 0.09 2 (2, 3) 2 (2 ,2) −1.065 0.288 ICs characteristics Education, n 6.221 0.013 1.070 0.301 University and above 135 69 66 35 100 High school and below 154 101 53 32 122 Marriage, n 2.396 0.122 0.976 0.323 Married 263 112 151 63 22 Other 26 7 19 4 200 Smoking, n 112.095 0.000 0.180 0.671 Yes 88 77 11 19 69 No 201 42 159 48 153 Alcohol consumption, n 73.343 0.000 0.205 0.651 Yes 80 65 15 20 60 No 209 54 155 47 162 Underlying condition, n 4.951 0.027 37.207 < 0.001 Yes 100 50 50 44 56 No 189 69 120 23 166 Acute events, n 1.664 0.197 2.987 0.084 Yes 38 12 26 13 54 No 251 107 144 54 197 Monthly income, n 24.238 0.000 11.917 0.018 < 3,000 64 17 47 15 49 3,000− 100 37 63 33 67 6,000− 43 20 23 9 34 10,000− 64 29 35 7 57 ≥ 20,000 18 16 2 3 15 Monthly cost, n 7.221 0.125 2.066 0.724 < 3,000 62 25 37 15 47 3,000− 101 43 58 25 76 6,000− 65 19 46 13 52 10,000− 39 21 18 7 32 ≥ 20,000 22 11 11 7 15 Note. x ± s, mean ± standard error; M (P25, P75), Median (interquartile range); ADLS, Activities of Daily Living Scale; BADLS, Basic Activities of Daily Living Scale; IADLS, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale. -

Most IC households (29.8%) spent > RMB 100,000 on medical expenses over the past year. This group was followed by the RMB 10,000–RMB 50,000 group (59, 20.4%) and the RMB 50,000–RMB 100,000 group (58, 20.1%). Regarding the duration of caregiving, the majority of ICs spent < 6 months on caregiving (176, 60.9%), while 197 (68.2%) spent six months to one year caregiving. A total of 133 (46.0%) ICs spent more than eight hours per day caring for patients. Additionally, 100 ICs (34.6%) had at least one underlying medical condition, 38 (13.1%) experienced acute events during caregiving, 64 (22.1%) had a monthly income of < RMB 3,000, and the monthly expenses of 22 (7.6%) exceeded RMB 20,000.

In the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) scale for lung cancer, the scores for the subscales self-esteem (SE), lack of family support (FS), financial problems (FP), disturbed schedule (DS), and health problems (HP) were 30.21 ± 3.70, 11.20 ± 3.93, 8.51 ± 3.41, 18.15 ± 3.85, and 9.75 ± 3.80, respectively. The subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores were 7.26 ± 4.69 and 6.84 ± 4.88, respectively. Among the 289 ICs of patients with lung cancer, 159 had no symptoms of anxiety, 69 had suspected symptoms, and 61 had definite symptoms, 163 had no symptoms of depression, 59 had suspected symptoms, and 67 had definite symptoms. Based on the overall HADS score, 53 (18.34%) ICs had suspected symptoms of depression and anxiety, and 32 (11.07%) had definite symptoms of depression and anxiety. The ISI score was 8.96 ± 6.71; according to the score classification, 139 ICs had no insomnia, 83 had mild insomnia, 53 had moderate insomnia, and 14 had severe insomnia (Table 2).

Table 2. Burden of lung cancer patients’ ICs

Basic characteristics Both

(n = 289)Male

(n = 119)Female

(n = 170)T / χ2 P value Insomnia

(n = 150)Non-insomnia

(n = 139)T / χ2 P value CRA, x ± s SE 30.21 ± 3.70 30.36 ± 3.65 30.11 ± 3.75 −0.563 0.574 30.09 ± 3.34 30.35 ± 4.07 0.573 0.567 FS 11.20 ± 3.93 10.77 ± 3.75 11.51 ± 4.04 1.581 0.115 11.51 ± 3.91 10.87 ± 3.94 −1.376 0.170 FP 8.51 ± 3.41 8.27 ± 3.54 8.68 ± 3.31 1.001 0.318 9.45 ± 3.33 7.50 ± 3.20 −5.068 < 0.001 DS 18.15 ± 3.85 17.90 ± 3.76 18.32 ± 3.91 0.922 0.357 19.41 ± 3.28 16.79 ± 3.96 −6.083 < 0.001 HP 9.75 ± 3.80 9.02 ± 3.65 10.27 ± 3.82 2.796 0.006 11.36 ± 3.62 8.02 ± 3.17 −8.305 < 0.001 HADS HAS 7.26 ± 4.69 6.58 ± 4.50 7.74 ± 4.77 2.074 0.039 9.31 ± 4.67 5.04 ± 3.58 −8.766 < 0.001 HDS 6.84 ± 4.88 6.04 ± 4.56 7.40 ± 5.04 2.344 0.020 9.25 ± 4.45 4.24 ± 3.90 −10.151 < 0.001 HAS Group, n 6.576 0.037 39.522 < 0.001 No symptoms 159 76 83 59 100 Suspected symptoms 69 24 45 40 29 Positive symptoms 61 19 42 51 10 HDS Group, n 6.390 0.041 50.182 < 0.001 No symptoms 163 77 86 55 108 Suspected symptoms 59 22 37 42 17 Positive symptoms 67 20 47 53 14 ISI, x ± s 8.96 ± 6.71 7.73 ± 6.00 9.81 ± 7.06 2.620 0.009 14.05 ± 5.19 3.45 ± 2.49 −22.861 < 0.001 ISI Group, n 8.664 0.034 289.00 < 0.001 No insomnia 139 64 75 139 0 Mild insomnia 83 31 52 0 83 Moderate insomnia 53 23 30 0 53 Sever insomnia 14 1 13 0 14 Note. x ± s, mean ± standard error; CRA, Caregiver Reaction Assessment; SE, Self-esteem; FS, Family Support; FP, Financial Problems; DS, Disturbed Schedule; HP, Health Problems; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAS, Hospital Anxiety Scale; HDS, Hospital Depression Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index. -

The ISI risk factors for ICs of patients with lung cancer were female gender, alcohol consumption, underlying medical conditions, years of caregiving, and monthly expenses. The ISI score of female ICs was 2.597 times higher than that of male ICs (95% confidence interval [CI]: –4.711 to 0.483, P = 0.016). The ISI score of ICs who consumed alcohol was 2.247 times higher than that of ICs who did not consume alcohol (95% CI: 0.170–4.325, P = 0.034). The ISI score of ICs with underlying medical conditions was 3.579 times higher than that of ICs without such conditions (95% CI: 1.677–5.480, P < 0.001). The ISI score of ICs increased 1.236 times (95% CI: 0.361–2.112, P = 0.006) for each increase in the number of years of caregiving. The ISI score for ICs decreased 0.975 times (95% CI: 0.263–1.687, P = 0.007) for each increase in monthly expenses. The ISI protective factors were the number of years since cancer diagnosis and the ICs’ monthly income. The ISI score of ICs decreased by 0.838 times (95% CI: –1.489 to 0.188, P = 0.012) for each additional year in which the patient had cancer, and decreased by 0.990 times (95% CI: –1.748 to 0.233, P = 0.011) for each increase in their monthly income. Alcohol consumption, underlying medical conditions, and monthly expenses were risk factors for insomnia in the ICs of patients with lung cancer, whereas monthly income was a protective factor (Table 3).

Table 3. Risk factors of insomnia among lung cancer patients’ ICs

Variables OR LL UL P value Years diagnosed with cancers 1.312 1.004 1.715 0.047 Marriage 4.548 1.490 13.881 0.008 Education 0.651 0.318 1.329 0.008 Patients’ sex 1.048 0.494 2.223 0.903 Sex 2.071 0.908 4.719 0.083 Smoking 0.509 0.211 1.232 0.134 Alcohol consumption 0.513 0.221 1.190 0.120 Underlying condition 0.688 0.323 1.466 0.333 Acute events 1.757 0.712 4.333 0.211 Years of caregiving 0.668 0.460 0.970 0.034 Monthly income 0.862 0.625 1.189 0.366 Monthly cost 0.936 0.702 1.249 0.653 Age 0.988 0.957 1.020 0.452 Patients Age 0.979 0.949 1.020 0.183 Patients ADL score 0.985 0.947 1.020 0.444 Anxiety & depression 0.517 0.216 1.234 0.137 Anxiety or depression 0.136 0.607 0.303 < 0.001 Note. ICs, Informal Caregivers; ADLS, Activities of Daily Living Scale; OR , Odds Ratio; LL, Lower limits, UL, Upper Limits. The ICs of patients with lung cancer were classified into four categories according to their ISI scores: no insomnia, mild insomnia, moderate insomnia, and severe insomnia. Ordinal logistic regression was performed; however, because it did not satisfy the test of parallel lines (P < 0.001), nominal logistic regression was used instead. Given the small sample size of the severe insomnia group, it was combined with the moderate insomnia group to form a moderate-to-severe insomnia group. Using the no-insomnia group as the reference, the ISI score of ICs was set as the dependent variable, while the ICs’ marital status, education level, gender, smoking status, alcohol consumption, underlying medical conditions, experience of acute events, years of caregiving, income, and expenses, as well as the patients’ number of years with cancer, gender, age, and ADL score were set as independent variables for analysis. The results of the model likelihood ratio test were χ2 = 152.995, P < 0.001.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that for lung cancer patients with higher ADL scores, the likelihood of ICs’ ISI scores indicating definite symptoms was OR = 0.940 (95% CI: 0.898–0.983, P = 0.007). Compared to female ICs, the likelihood of a male IC’s ISI score indicating mild insomnia was OR = 0.263 (95% CI: 0.095–0.729, P = 0.010), and moderate to severe insomnia was OR = 0.171 (95% CI: 0.046–0.635, P = 0.008). Compared to ICs who did not consume alcohol, the likelihood of the ISI scores of ICs who consumed alcohol indicating moderate-to-severe insomnia was OR = 3.745 (95% CI: 1.086–12.821, P = 0.037). Compared to ICs without underlying medical conditions, the likelihood of ICs with underlying medical conditions showing ISI scores indicating mild insomnia was OR = 11.765 (95% CI: 4.065–34.483, P < 0.001). Compared to ICs with < 6 months of caregiving experience, ICs with 5–10 years of caregiving experience showed a higher risk of moderate-to-severe insomnia based on their ISI scores (OR = 37.037, 95% CI: 2.141–500.000, P = 0.013). Compared to ICs with monthly expenses of < RMB 3,000, ICs with monthly expenses of RMB 6,000–RMB 10,000 were 5.714 times more likely to have moderate-to-severe insomnia, as shown by their ISI scores (95% CI: 1.074–30.303, P = 0.041). Compared to ICs with monthly expenses of < RMB 3,000, ICs with monthly expenses of RMB 10,000–RMB 20,000 were 11.236 times more likely to have moderate-to-severe insomnia, as shown by their ISI scores (95% CI: 1.883–66.667, P = 0.008). Finally, compared to ICs with monthly expenses of < RMB 3000, ICs with monthly expenses of > RMB 20,000 were 0.183 more likely to suffer from mild insomnia, as shown by their ISI scores (95% CI: 0.034–0.989, P = 0.049; Table 4).

Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression of insomnia among ICs of lung cancer patients

Variables Mild insomnia Moderate and severe insomnia OR 95% CI P value OR 95% CI P value LL UL LL UL Patients’ age 0.973 0.940 1.006 0.105 1.014 0.969 1.060 0.549 ICs’ age 1.021 0.982 1.062 0.287 0.987 0.948 1.029 0.549 ADL 0.989 0.943 1.037 0.646 0.940 0.898 0.983 0.007 Years with cancers 1.359 0.890 2.075 0.155 1.131 0.801 1.597 0.484 Marriage 0.523 0.166 1.645 0.267 0.649 0.120 3.521 0.617 Education 0.898 0.382 2.110 0.805 2.857 0.985 8.333 0.053 Patients’ sex 0.648 0.280 1.499 0.311 1.464 0.513 4.167 0.476 ICs sex 0.263 0.095 0.729 0.010 0.171 0.046 0.635 0.008 Smoking 1.757 0.662 4.651 0.258 1.656 0.489 5.587 0.418 Drinking 2.451 0.973 6.173 0.057 3.745 1.086 12.821 0.037 Underlying diseases 0.908 0.374 2.203 0.831 11.765 4.065 34.483 < 0.001 Acute events 1.855 0.622 5.525 0.268 1.055 0.352 3.155 0.924 Years of caregiving, y < 0.5 Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. 0.5− − − − 0.998 22.727 0.920 500.000 0.056 1− − − − 0.998 7.463 0.308 166.667 0.217 3− − − − 0.998 4.405 0.185 100.000 0.359 5− − − − 0.998 37.037 2.141 500.000 0.013 ≥ 10 − − − 0.997 0.912 0.912 0.912 − Monthly income < 3,000 Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. 3,000− 0.469 0.079 2.801 0.407 0.242 0.023 2.532 0.237 6,000− 0.948 0.181 4.975 0.950 0.108 0.012 1.007 0.051 10,000− 0.310 0.058 1.650 0.170 0.187 0.020 1.773 0.144 ≥ 20,000 0.797 0.171 3.704 0.772 2.242 0.269 18.868 0.455 Monthly expenses < 3,000 Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. 3,000− 2.066 0.448 9.524 0.352 4.630 0.903 23.810 0.066 6,000− 0.670 0.160 2.801 0.583 5.714 1.074 30.303 0.041 10,000− 1.205 0.274 5.291 0.805 11.236 1.883 66.667 0.008 ≥ 20,000 0.183 0.034 0.989 0.049 0.853 0.123 5.917 0.872 Note. ICs, Informal Caregivers; ADLS, Activities of Daily Living Scale. Ref, Reference group; −: means sample size in the group was too small to estimate; OR, Odds Ratio; LL, Lower Limits, UL, Upper Limits. -

ICs are increasingly becoming the primary providers for patients with cancer in both European countries and the United States, and most ICs are adults[14]. Dementia, stroke, and cancer require substantial effort and commitment from ICs. A study estimating the time spent on caregiving revealed that ICs provided an average of 20.5 hours of care per week and 20% of ICs provided care for more than 40 hours per week[15]. ICs play an indispensable role in supporting patients during their treatment course, particularly in the progressive stage. Previous studies have shown that ICs report lower perceived burdens and better clinical interaction skills in a more open and honest family communication environment[16]. However, most ICs lack professional skills and have limited clinical knowledge regarding caregiving. Moreover, chronic overwork and stress may lead to anxiety, depression, sleep problems, mental health issues, and post-traumatic stress disorder[17-20], it can even affect an individual’s immune function and hormone release[21,22]. Additionally, ICs for terminally ill patients may be concerned about the patient’s death. It is widely accepted that caring for patients with cancer involves a greater burden of care than caring for older adults or patients with other chronic diseases such as diabetes[23,24].

Overall, lung cancer is a major cause of death in the general population[25]. Therefore, ICs of patients with lung cancer have considerable responsibilities and duties. Early targeted interventions, such as psychoeducation and other interventions that have proven to be effective, should be provided to ICs of lung and colorectal cancer patients promptly according to the severity of the patient’s disease[26]. A long-term sustainable approach to intervention and counseling can be adopted for ICs of patients with breast cancer.

ICs are characterized by an emotionally charged caregiving process that provides concrete and helpful support[27]. ICs are not only responsible for caregiving but also for daily activities, such as sourcing social and financial support for patients, making hospital appointments, and coordinating their own work lives. Simultaneously, they are required to provide physical and psychological support and guidance to patients with cancer. The proportion of severe insomnia among ICs with lung cancer in this study was 22.8%, which was slightly higher than that previously reported. However, despite using a different sleep assessment tool, a similar prevalence of insomnia (16.3%) was observed in this study[28].

Globally, the burden of cancer is expected to increase by 50% by 2040 owing to an increase in the aging population, at which point the number of new cancer cases worldwide will reach nearly 30 million[29]. This impact is most pronounced in countries undergoing social and economic transition. The GLOBOCAN 2020 database revealed[30] that providing cancer prevention and care in transitioning countries is critical for global cancer control. As a transitioning country, China has a substantial cancer incidence and mortality burden. Therefore, ICs require urgent attention and support as a powerful complement to professional care. While cancer and non-cancer caregivers have several similarities, the informal cancer caregiving experience has several unique characteristics[31]. Social support from other families with caregiving experience and professional institutions will empower ICs to cope with stress and ease their caregiving experiences, thereby reducing caregiver stress.

Implications for cancer patients and ICs: cancer patients and ICs should be made aware that cancer affects not only patients but also their ICs. These two factors are mutually influential and form an inseparable entity. Cancer patients, with their ICs, can control relevant factors and correct modifiable factors. The mental health of patients with cancer is closely related to their ICs, and changes in patients with cancer can affect the psychological state of the ICs. Similarly, changes in the ICs can affect patients with cancer. ICs can evaluate their modifiable factors through nomograms and related factors to help them face cancer positively together with patients. They can proactively seek social support, appropriate training for caregiving skills, and pathways for intervention and counseling. Additionally, ICs can seek respite and rotate their duties by adjusting care hours, finding help, etc. Cancer patients and ICs should be aware that it is necessary to actively seek help and support, which will benefit both patients and their ICs.

Implications for medical care: Oncology clinicians should assess the abilities and stress levels of ICs and provide them with additional care support services. In the community, primary healthcare workers should screen ICs promptly and provide counseling and interventions to ensure that ICs remain in good physical and mental health. Referral pathways should be established for ICs who are unable to receive interventions and counseling at the primary care level to determine feasible and effective interventions and counseling. This study recommends that future clinical practice in the diagnosis and care of patients with cancer should focus not only on patients but also on their ICs. In particular, ICs with long-term caregiving responsibilities should receive timely counseling and attention to relieve psychological stress. During the clinical treatment process, emphasis should be placed on ICs and professional help should be provided based on the skills and resources available. For example, ICs can be provided with professional care knowledge and skills training. Other methods such as reminding ICs to obtain adequate rest and respite can also have positive effects on ICs.

Social implications: attention should be paid to ICs and corresponding policies and measures should be formulated to safeguard them. This includes but is not limited to, financial support, social resource support, and support for care information technology. Currently, ICs are responsible for the vast majority of in-home cancer care, and social support plays an integral role in their physical and mental health. Therefore, a robust social support system can effectively assist ICs of cancer patients in providing high-quality and effective care, thereby reducing the pressure of caregiving at the societal level. The construction of respite and rotation platforms for ICs should be actively explored to supplement and rotate their duties with professional caregiving institutions. Novel technologies, such as smart robots and telemedicine, which can share the ICs’ burdens, are also worth extending to the ICs of patients with cancer.

This study included 447 ICs of patients with different types of cancer, and the burden of ICs for patients with cancer was assessed using standardized scales. This assessment involved the evaluation of caregiver burden, anxiety, depression, and sleep. This study’s focus on the ICs of cancer patients was not limited to the state of the ICs but also extended to improving the emotional and physical states of cancer patients through the close connection of these patients with their ICs.

This study had several limitations. First, only the ICs of hospitalized patients with cancer were investigated. Therefore, future studies should examine the ICs’ burden in the community and other contexts of long-term in-home care. Second, the patients’ cancer stages and severity were not analyzed, which may have introduced some bias. Third, ICs with organic diseases were not excluded from this study, which may have introduced some bias. Fourth, the potential association between mental status and insomnia was not analyzed due to a lack of relevant data. In the future, our research group will further examine the ICs of cancer patients in the community and add necessary procedures to our study to obtain more useful evidence for lung cancer ICs interventions and healthcare.

-

This study revealed that 51.9% of ICs of patients with lung cancer experienced insomnia. Patients’ ADL, ICs gender, alcohol consumption, underlying medical conditions, caregiving duration, and monthly expenses were influencing factors. Prompt screening and early intervention, such as scale evaluation and psychological support offered by hospitals or communities, should be provided to improve ICs’ health. Future studies should include larger sample sizes and multiple centers to promote the generalization of this study’s findings.

-

All participants provided informed consent (Clinical research registration no. ChiCTR2000041546; hospital ethics no. S2020-445-02).

doi: 10.3967/bes2023.099

Insomnia Burden among Informal Caregivers of Hospitalized Lung Cancer Patients and Its Influencing Factors

-

Abstract:

Objective This study aimed to reveal the insomnia burden and relevant influencing factors among informal caregivers (ICs) of hospitalized patients with lung cancer. Methods A cross-sectional study on ICs of hospitalized patients with lung cancer was conducted from December 31, 2020 to December 31, 2021. ICs’ burden was assessed using the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). Linear and logistic regression models were used to identify the influencing factors. Results Among 289 ICs of hospitalized patients with lung cancer, 83 (28.72%), 53 (18.34%), and 14 (4.84%) ICs experienced mild, moderate, and severe insomnia, respectively. The scores concerning self-esteem, lack of family support, financial problems, disturbed schedule, and health problems were 4.32 ± 0.53, 2.24 ± 0.79, 2.84 ± 1.14, 3.63 ± 0.77, and 2.44 ± 0.95, respectively. ICs with higher Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADLS) scores were associated with a lower risk of insomnia, with an odd ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.940 (0.898–0.983). Among the ICs, female gender (OR = 2.597), alcohol consumption (OR = 3.745), underlying medical conditions (OR = 11.765), long-term caregiving experience (OR = 37.037), and higher monthly expenses (OR = 5.714) were associated with a high risk of insomnia. Conclusion Of the hospitalized patients with lung cancer, 51.9% experienced insomnia. Patients’ ADL, ICs gender, alcohol consumption, underlying medical conditions, caregiving duration, and monthly expenses were influencing factors. Therefore, prompt screening and early intervention for ICs of patients with lung cancer is necessary. -

Key words:

- Informal caregivers /

- Insomnia /

- Risk factors /

- Cross-sectional study /

- Lung cancer

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: 2) CONFLICT OF INTEREST: -

Table 1. Basic characteristics of lung cancer patients’ ICs

Variables Both

(n = 289)Male

(n = 119)Female

(n = 170)T / χ2 / Z P value Insomnia

(n = 67)Non-insomnia

(n = 222)T / χ2 / Z P value Age, years, x ± s 49.44 ± 12.52 47.16 ± 12.31 51.04 ± 12.46 2.615 0.009 52.96 ± 12.66 48.38 ± 12.31 −2.649 0.009 BADLs (P25, P75) 0 (0, 2.5) 0 (0, 3) 0.5 (0, 2.25) −2.133 0.033 1 (0, 4) 0 (0, 2) −3.029 0.003 IADLs (P25, P75) 2 (0, 7) 2 (0, 8) 3 (0,7) −0.634 0.526 4 (0, 10) 2 (0, 6) −2.552 0.012 Years diagnosed with Cancer

(P25, P75)2 (2, 2) 2 (1, 2) 2 (2,2.25) −1.694 0.09 2 (2, 3) 2 (2 ,2) −1.065 0.288 ICs characteristics Education, n 6.221 0.013 1.070 0.301 University and above 135 69 66 35 100 High school and below 154 101 53 32 122 Marriage, n 2.396 0.122 0.976 0.323 Married 263 112 151 63 22 Other 26 7 19 4 200 Smoking, n 112.095 0.000 0.180 0.671 Yes 88 77 11 19 69 No 201 42 159 48 153 Alcohol consumption, n 73.343 0.000 0.205 0.651 Yes 80 65 15 20 60 No 209 54 155 47 162 Underlying condition, n 4.951 0.027 37.207 < 0.001 Yes 100 50 50 44 56 No 189 69 120 23 166 Acute events, n 1.664 0.197 2.987 0.084 Yes 38 12 26 13 54 No 251 107 144 54 197 Monthly income, n 24.238 0.000 11.917 0.018 < 3,000 64 17 47 15 49 3,000− 100 37 63 33 67 6,000− 43 20 23 9 34 10,000− 64 29 35 7 57 ≥ 20,000 18 16 2 3 15 Monthly cost, n 7.221 0.125 2.066 0.724 < 3,000 62 25 37 15 47 3,000− 101 43 58 25 76 6,000− 65 19 46 13 52 10,000− 39 21 18 7 32 ≥ 20,000 22 11 11 7 15 Note. x ± s, mean ± standard error; M (P25, P75), Median (interquartile range); ADLS, Activities of Daily Living Scale; BADLS, Basic Activities of Daily Living Scale; IADLS, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale. Table 2. Burden of lung cancer patients’ ICs

Basic characteristics Both

(n = 289)Male

(n = 119)Female

(n = 170)T / χ2 P value Insomnia

(n = 150)Non-insomnia

(n = 139)T / χ2 P value CRA, x ± s SE 30.21 ± 3.70 30.36 ± 3.65 30.11 ± 3.75 −0.563 0.574 30.09 ± 3.34 30.35 ± 4.07 0.573 0.567 FS 11.20 ± 3.93 10.77 ± 3.75 11.51 ± 4.04 1.581 0.115 11.51 ± 3.91 10.87 ± 3.94 −1.376 0.170 FP 8.51 ± 3.41 8.27 ± 3.54 8.68 ± 3.31 1.001 0.318 9.45 ± 3.33 7.50 ± 3.20 −5.068 < 0.001 DS 18.15 ± 3.85 17.90 ± 3.76 18.32 ± 3.91 0.922 0.357 19.41 ± 3.28 16.79 ± 3.96 −6.083 < 0.001 HP 9.75 ± 3.80 9.02 ± 3.65 10.27 ± 3.82 2.796 0.006 11.36 ± 3.62 8.02 ± 3.17 −8.305 < 0.001 HADS HAS 7.26 ± 4.69 6.58 ± 4.50 7.74 ± 4.77 2.074 0.039 9.31 ± 4.67 5.04 ± 3.58 −8.766 < 0.001 HDS 6.84 ± 4.88 6.04 ± 4.56 7.40 ± 5.04 2.344 0.020 9.25 ± 4.45 4.24 ± 3.90 −10.151 < 0.001 HAS Group, n 6.576 0.037 39.522 < 0.001 No symptoms 159 76 83 59 100 Suspected symptoms 69 24 45 40 29 Positive symptoms 61 19 42 51 10 HDS Group, n 6.390 0.041 50.182 < 0.001 No symptoms 163 77 86 55 108 Suspected symptoms 59 22 37 42 17 Positive symptoms 67 20 47 53 14 ISI, x ± s 8.96 ± 6.71 7.73 ± 6.00 9.81 ± 7.06 2.620 0.009 14.05 ± 5.19 3.45 ± 2.49 −22.861 < 0.001 ISI Group, n 8.664 0.034 289.00 < 0.001 No insomnia 139 64 75 139 0 Mild insomnia 83 31 52 0 83 Moderate insomnia 53 23 30 0 53 Sever insomnia 14 1 13 0 14 Note. x ± s, mean ± standard error; CRA, Caregiver Reaction Assessment; SE, Self-esteem; FS, Family Support; FP, Financial Problems; DS, Disturbed Schedule; HP, Health Problems; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAS, Hospital Anxiety Scale; HDS, Hospital Depression Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index. Table 3. Risk factors of insomnia among lung cancer patients’ ICs

Variables OR LL UL P value Years diagnosed with cancers 1.312 1.004 1.715 0.047 Marriage 4.548 1.490 13.881 0.008 Education 0.651 0.318 1.329 0.008 Patients’ sex 1.048 0.494 2.223 0.903 Sex 2.071 0.908 4.719 0.083 Smoking 0.509 0.211 1.232 0.134 Alcohol consumption 0.513 0.221 1.190 0.120 Underlying condition 0.688 0.323 1.466 0.333 Acute events 1.757 0.712 4.333 0.211 Years of caregiving 0.668 0.460 0.970 0.034 Monthly income 0.862 0.625 1.189 0.366 Monthly cost 0.936 0.702 1.249 0.653 Age 0.988 0.957 1.020 0.452 Patients Age 0.979 0.949 1.020 0.183 Patients ADL score 0.985 0.947 1.020 0.444 Anxiety & depression 0.517 0.216 1.234 0.137 Anxiety or depression 0.136 0.607 0.303 < 0.001 Note. ICs, Informal Caregivers; ADLS, Activities of Daily Living Scale; OR , Odds Ratio; LL, Lower limits, UL, Upper Limits. Table 4. Multinomial logistic regression of insomnia among ICs of lung cancer patients

Variables Mild insomnia Moderate and severe insomnia OR 95% CI P value OR 95% CI P value LL UL LL UL Patients’ age 0.973 0.940 1.006 0.105 1.014 0.969 1.060 0.549 ICs’ age 1.021 0.982 1.062 0.287 0.987 0.948 1.029 0.549 ADL 0.989 0.943 1.037 0.646 0.940 0.898 0.983 0.007 Years with cancers 1.359 0.890 2.075 0.155 1.131 0.801 1.597 0.484 Marriage 0.523 0.166 1.645 0.267 0.649 0.120 3.521 0.617 Education 0.898 0.382 2.110 0.805 2.857 0.985 8.333 0.053 Patients’ sex 0.648 0.280 1.499 0.311 1.464 0.513 4.167 0.476 ICs sex 0.263 0.095 0.729 0.010 0.171 0.046 0.635 0.008 Smoking 1.757 0.662 4.651 0.258 1.656 0.489 5.587 0.418 Drinking 2.451 0.973 6.173 0.057 3.745 1.086 12.821 0.037 Underlying diseases 0.908 0.374 2.203 0.831 11.765 4.065 34.483 < 0.001 Acute events 1.855 0.622 5.525 0.268 1.055 0.352 3.155 0.924 Years of caregiving, y < 0.5 Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. 0.5− − − − 0.998 22.727 0.920 500.000 0.056 1− − − − 0.998 7.463 0.308 166.667 0.217 3− − − − 0.998 4.405 0.185 100.000 0.359 5− − − − 0.998 37.037 2.141 500.000 0.013 ≥ 10 − − − 0.997 0.912 0.912 0.912 − Monthly income < 3,000 Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. 3,000− 0.469 0.079 2.801 0.407 0.242 0.023 2.532 0.237 6,000− 0.948 0.181 4.975 0.950 0.108 0.012 1.007 0.051 10,000− 0.310 0.058 1.650 0.170 0.187 0.020 1.773 0.144 ≥ 20,000 0.797 0.171 3.704 0.772 2.242 0.269 18.868 0.455 Monthly expenses < 3,000 Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. Ref. 3,000− 2.066 0.448 9.524 0.352 4.630 0.903 23.810 0.066 6,000− 0.670 0.160 2.801 0.583 5.714 1.074 30.303 0.041 10,000− 1.205 0.274 5.291 0.805 11.236 1.883 66.667 0.008 ≥ 20,000 0.183 0.034 0.989 0.049 0.853 0.123 5.917 0.872 Note. ICs, Informal Caregivers; ADLS, Activities of Daily Living Scale. Ref, Reference group; −: means sample size in the group was too small to estimate; OR, Odds Ratio; LL, Lower Limits, UL, Upper Limits. -

[1] Chen WQ, Zheng RS, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016; 66, 115−32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338 [2] Cochrane A, Reid O, Woods S, et al. Variables associated with distress amongst informal caregivers of people with lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology, 2021; 30, 1246−61. doi: 10.1002/pon.5694 [3] Triantafillou J, Naiditch M, Repkova K, et al. Informal care in the long-term care system. European Overview Paper, 2011; 223037: 1−67. [4] National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregiving in the U. S. 2020.https://www.caregiving.org/caregiving-in-the-us-2020/.[2023-5-10 [5] Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer, 2015; 121, 1513−9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29223 [6] Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health, 2007; 97, 224−8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059337 [7] Wang YH, Hou WW, Feng YN, et al. Analyzing the status of self-reported health of 455 cases of female informal caregivers and its influencing factors. Chin Health Serv Manage, 2013; 30, 387−90, 396. (In Chinese [8] Li YL. The potential impacts of neuropsychiatric symptoms of senile dementia patients on distress of their informal caregivers. Nurs Integr Tradit Chin West Med, 2018; 4, 104−6. (In Chinese [9] Travis WD, Dacic S, Wistuba I, et al. IASLC multidisciplinary recommendations for pathologic assessment of lung cancer resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 2020; 15, 709−40. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.01.005 [10] Dizon DS T-BT, Steinhoff MM, et al. Breast cancer. In: Barakat RR, Markman M, Randall ME. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. 2009. [11] Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, et al. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep, 2011; 34, 601−8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601 [12] Duan Y, Sun SC. Questionaires in sleep disorders evaluation. World J Sleep Med, 2016; 3, 201−3. (In Chinese [13] Li EZ. The validity and reliability of severe insomnia index scale. Southern Medical University. 2018. (In Chinese [14] Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, et al. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA, 2014; 311, 1052−60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304 [15] National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. Caregiving in the U. S. 2009. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. [2023-5-8 [16] Campbell-Salome G, Fisher CL, Wright KB, et al. Impact of the family communication environment on burden and clinical communication in blood cancer caregiving. Psychooncology, 2022; 31, 1212−20. doi: 10.1002/pon.5910 [17] Yang M, Ma F, Lan B, et al. Validity of distress thermometer for screening of anxiety and depression in family caregivers of Chinese breast cancer patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy. Chin J Cancer Res, 2020; 32, 476−84. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.04.05 [18] Kotronoulas G, Wengström Y, Kearney N. Sleep and sleep-wake disturbances in care recipient-caregiver dyads in the context of a chronic illness: a critical review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2013; 45, 579−94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.03.013 [19] Krebber AMH, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology, 2014; 23, 121−30. doi: 10.1002/pon.3409 [20] Liang J, Lee SJ, Storer BE, et al. Rates and risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology among adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and their informal caregivers. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant, 2019; 25, 145−50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.08.002 [21] Kim Y, Chung ML, Lee H. Caregivers of patients with cancer: perceived stress, quality of life and immune function. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022; bmjspcare-2021-003205. [22] Pössel P, Mitchell AM, Harbison B, et al. Association of cancer caregiver stress and negative attribution style with depressive symptoms and cortisol: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer, 2022; 30, 4945−52. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-06866-1 [23] Hayden L, Dunne S. "Dying with dignity": a qualitative study with caregivers on the care of individuals with terminal cancer. Omega, 2022; 84, 1122−45. doi: 10.1177/0030222820930135 [24] Kim Y, Schulz R. Family caregivers' strains: comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. J Aging Health, 2008; 20, 483−503. doi: 10.1177/0898264308317533 [25] Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021; 71, 7−33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654 [26] Cheng QQ, Xu BB, Ng MSN, et al. Effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions among caregivers of patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud, 2022; 127, 104162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104162 [27] Toledano-Toledano F, Contreras-Valdez JA. Validity and reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) in family caregivers of children with chronic diseases. PLoS One, 2018; 13, e0206917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206917 [28] He Y, Sun LY, Peng KW, et al. Sleep quality, anxiety and depression in advanced lung cancer: patients and caregivers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022; 12: e194-e200. [29] Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin, 2022; 72, 7−33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708 [30] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021; 71, 209−49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [31] Washington KT, Pike KC, Demiris G, et al. Unique characteristics of informal hospice cancer caregiving. Support Care Cancer, 2015; 23, 2121−8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2570-z -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links