-

Melanocytes serve multiple functions in vertebrates by providing protective coloration and playing crucial roles in diverse physiological processes. They are also implicated in developing numerous diseases[1,2]. Developmentally, melanocytes in vertebrates originate from neural crest cells, and their developmental molecular regulatory mechanisms are highly conserved across vertebrate species[2-4]. Consequently, leveraging various animal models allows the establishment of models for human melanocyte-related diseases, facilitating the study of the molecular mechanisms driving the occurrence, progression, and drug resistance of these diseases and the development of relevant therapeutic strategies[1,5-7].

Nevi, which are highly prevalent, are recognized as benign skin lesions, with nearly everyone having multiple nevi that can manifest at any body location[8,9]. While some nevi are inconsequential, others are life-threatening[10]. Most nevi, particularly those associated with BRAFV600E, are believed to originate from the malignant proliferation of melanocytes followed by a subsequent transition to a senescent state[11-13]. In the context of melanoma development, it has been proposed that melanocytes initially harbor the BRAFV600E mutation, leading to benign nevi formation[13-18]. Subsequently, additional gene mutations in TERT, PTEN, CDKN2A, CDKN2B, and TP53 enable senescent melanocytes within benign nevi to regain their malignant proliferation potential[14]. Consequently, benign nevi can progress to dysplastic nevi, in situ melanoma, and metastatic melanoma[13]. To unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying BRAFV600E-related melanoma and effectively control its onset during the early stages, various animal models expressing BRAFV600E in melanocytes, specifically animal models of BRAFV600E-related nevi formation have been established[5,6]. These models are used to elucidate the intricate molecular regulatory mechanisms governing the transition of melanocytes from proliferative to senescent states after BRAFV600E-induced proliferation[5,6,19-25].

When constructing animal models of human diseases, it is crucial to faithfully replicate the molecular events that occur during disease onset and progression. Such models can effectively reveal the mechanisms underlying human diseases and facilitate exploring improved therapeutic strategies. Additionally, according to the classification by the Cancer Genome Atlas Network, cutaneous melanoma can be categorized into four types: mutant BRAF, mutant NRAS, mutant NF1, and triple wild-type[26]. Therefore, this study primarily focused on reviewing the subtypes of cutaneous melanoma characterized by BRAFV600E mutation. Herein, we present an overview of the molecular mechanisms responsible for melanocyte senescence induced by BRAFV600E, along with animal models specifically related to BRAFV600E-induced nevi.

-

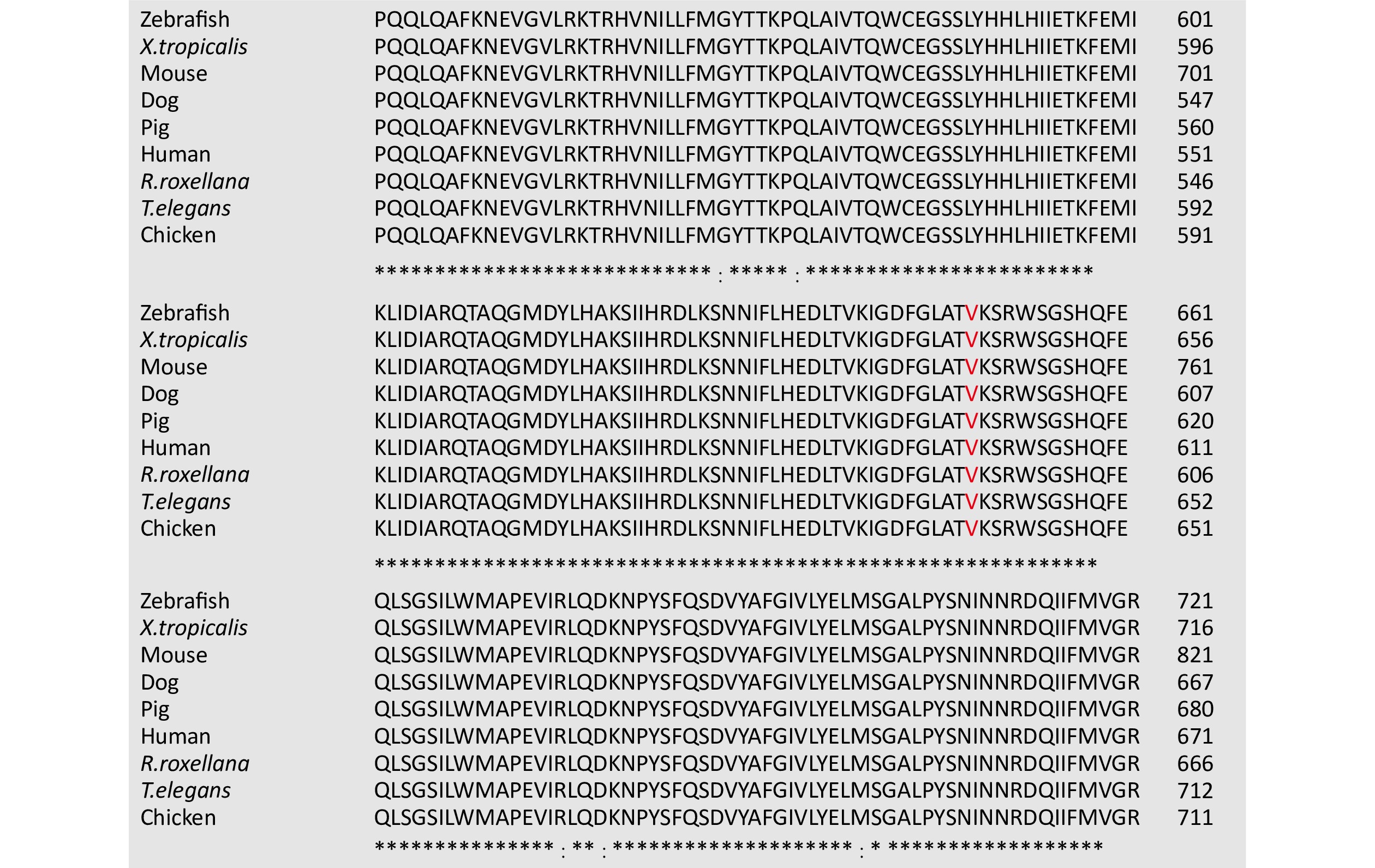

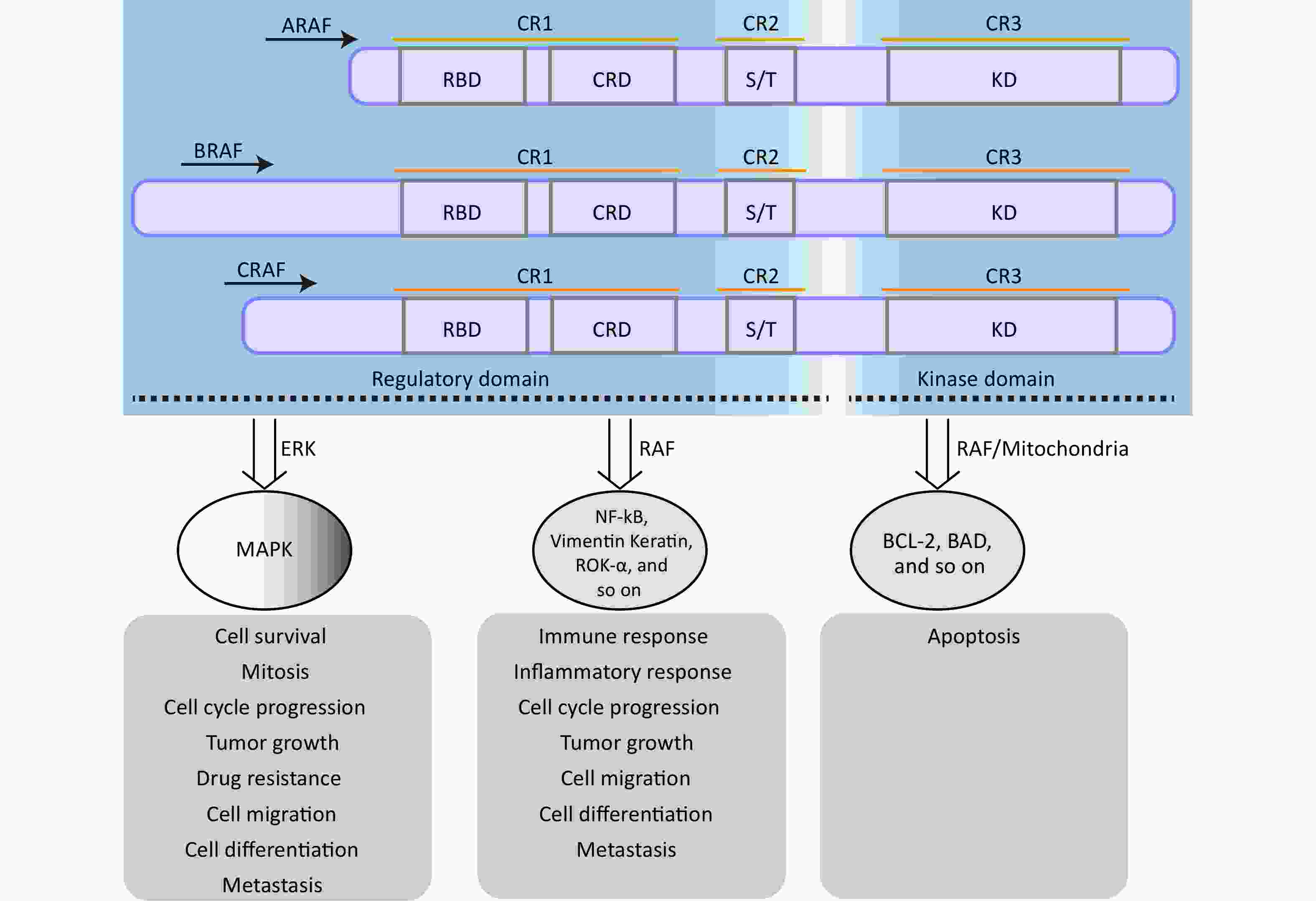

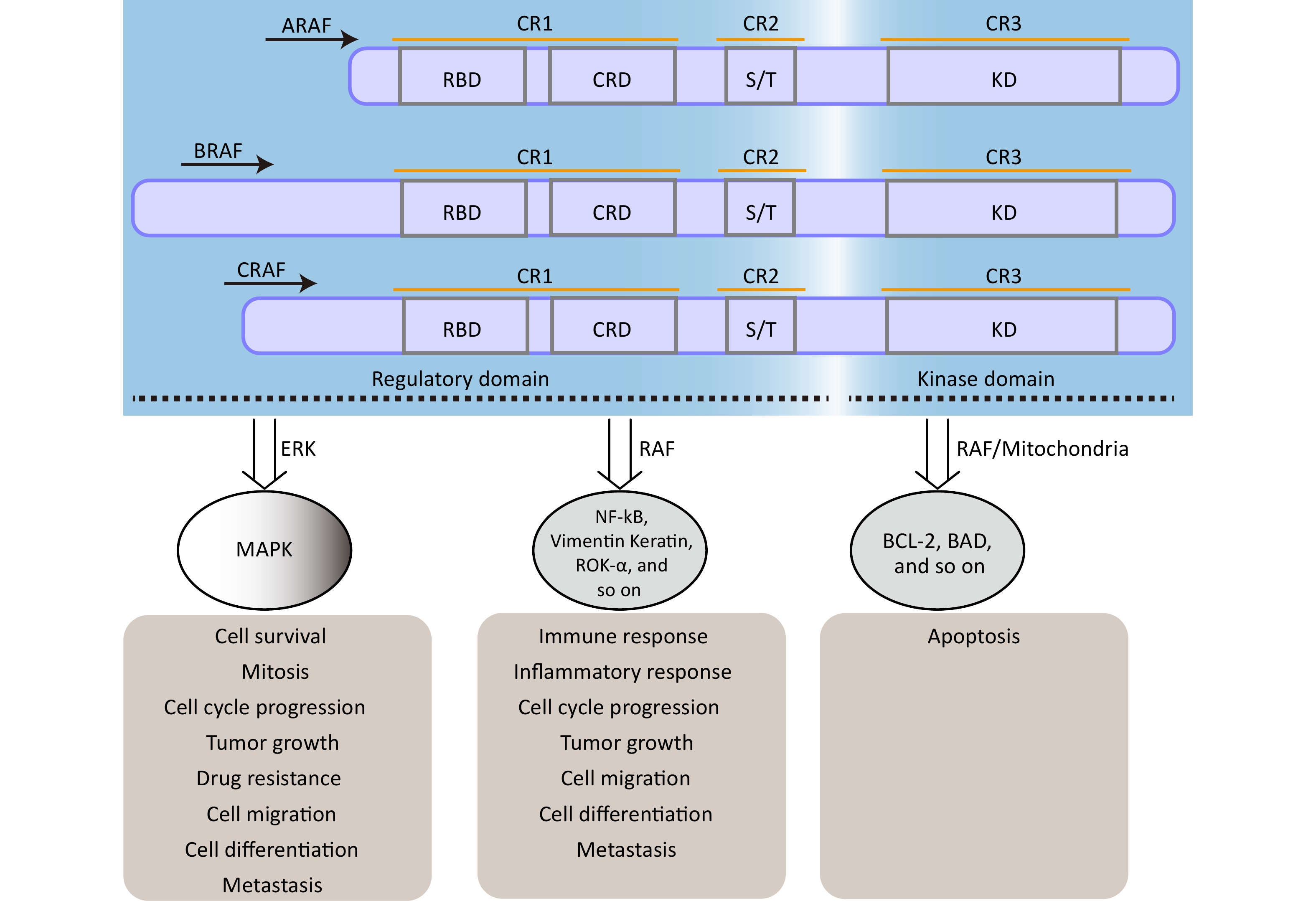

The rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF) family of Ser/Thr kinases (ARAF, BRAF, and CRAF) is a fundamental component of the RAS-RAF-mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) [mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)] signaling pathway, a conserved membrane-to-nucleus signaling module involved in various physiological processes[27,28]. The structural organization and function of RAF kinases are conserved across eukaryotes, and dysregulation of this pathway has been implicated in numerous diseases, including various cancers and vascular diseases[29-31]. As shown in Figure 1, structurally, RAF kinases possess a homologous structure consisting of three conserved regions (CR1, CR2, and CR3)[32]. CR1 encompasses a cysteine-rich domain (CRD/C1 domain) and recognized RAS-binding domain, whereas CR2 contains a serine/threonine-rich domain that contributes to the formation of a regulatory protein-binding site upon phosphorylation[27,32]. Detailed information regarding the structure and functional description of the RAF family proteins can be found in other papers[32]. The regulation of RAF kinase activity in quiescent cells involves intramolecular interactions between the CRD and KD domains and the binding of a 14-3-3 dimer to phosphorylation sites in CR2 and CR3, which maintains an auto-inhibited conformation, resulting in the inactivation of cytosolic RAF kinase monomers[27]. However, upon activation of RAS, cytosolic RAF kinases are recruited and directly interact with the plasma membrane-located GTP-bound RAS through the RAS-binding domain[33,34]. This disrupts the auto-inhibited conformation, promotes homo- and heterodimerization of RAF kinases, and triggers multiple phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events, ultimately leading to activation of the MAPK signaling pathway[27,33].

Figure 1. The structure and function of RAF family proteins. The S/T region is an area rich in serine/threonine residues. RAF, rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activatedprotein kinase.

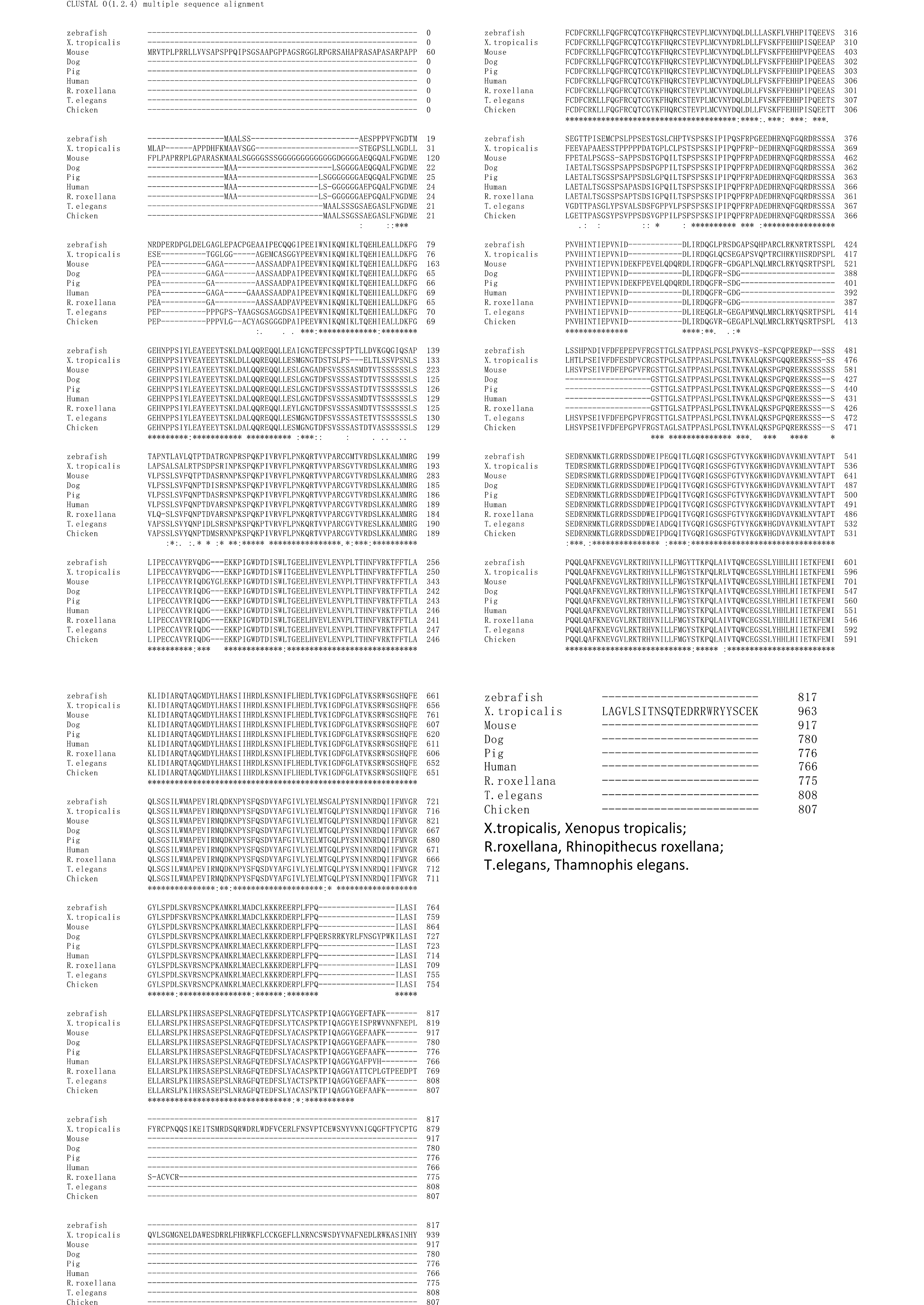

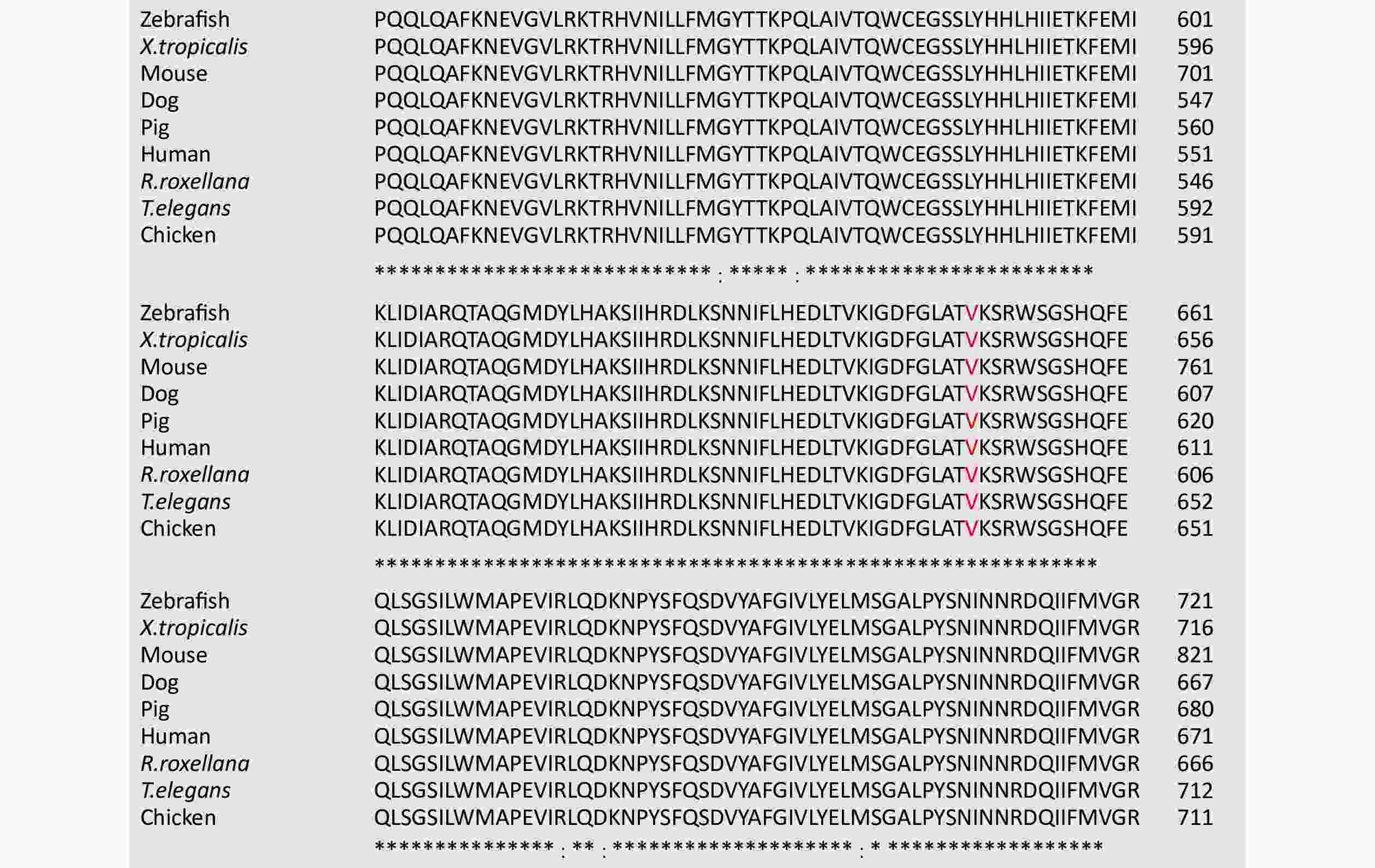

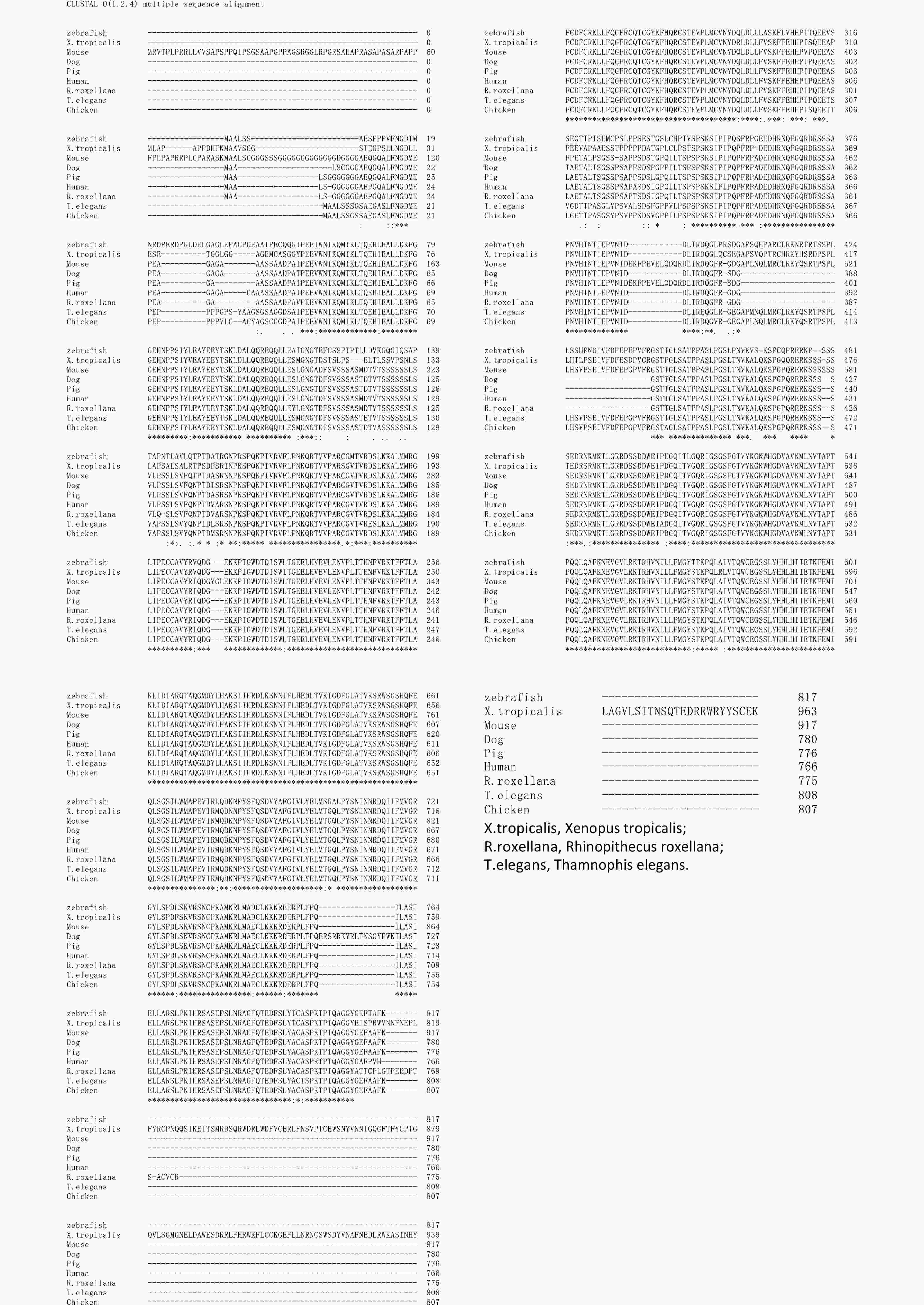

BRAF is an RAF kinase with a high frequency of oncogenic mutations[24,35]. Mutations in BRAF are detected in approximately 80% of benign nevi and 60% of cutaneous melanomas, with an incidence of approximately 8% in human tumors[34,36,37]. Of these mutations, the most common BRAF mutation is the 1799 T>A substitution (BRAFT1799A), which leads to a V600E amino acid substitution in the KD (BRAFV600E)[34,37]. This mutation is classified as a monomerically activating mutation that eliminates the reliance of BRAF on dimerization and RAS activation to exert its kinase activity[38]. As a result, BRAFV600E exhibits several-fold kinase hyperactivation and sustained kinase activity, driving uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumorigenesis[30,34,37]. The structure of vertebrate BRAF is highly conserved, particularly in the essential kinase domains (CR1, CR2, and CR3) of zebrafish, Xenopus tropicalis, mice, pigs, monkeys, and humans (Supplementary Figure S1, available in www.besjournal.com). In particular, the amino acid sequence surrounding the 600th residue (V) in the CR3 region of BRAF exhibits a high degree of uniformity (Figure 2). This highly conserved characteristic has facilitated the establishment of numerous animal models, including mice and zebrafish with BRAFV600E mutations, to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying BRAFV600E-associated diseases[5,25,39-42].

-

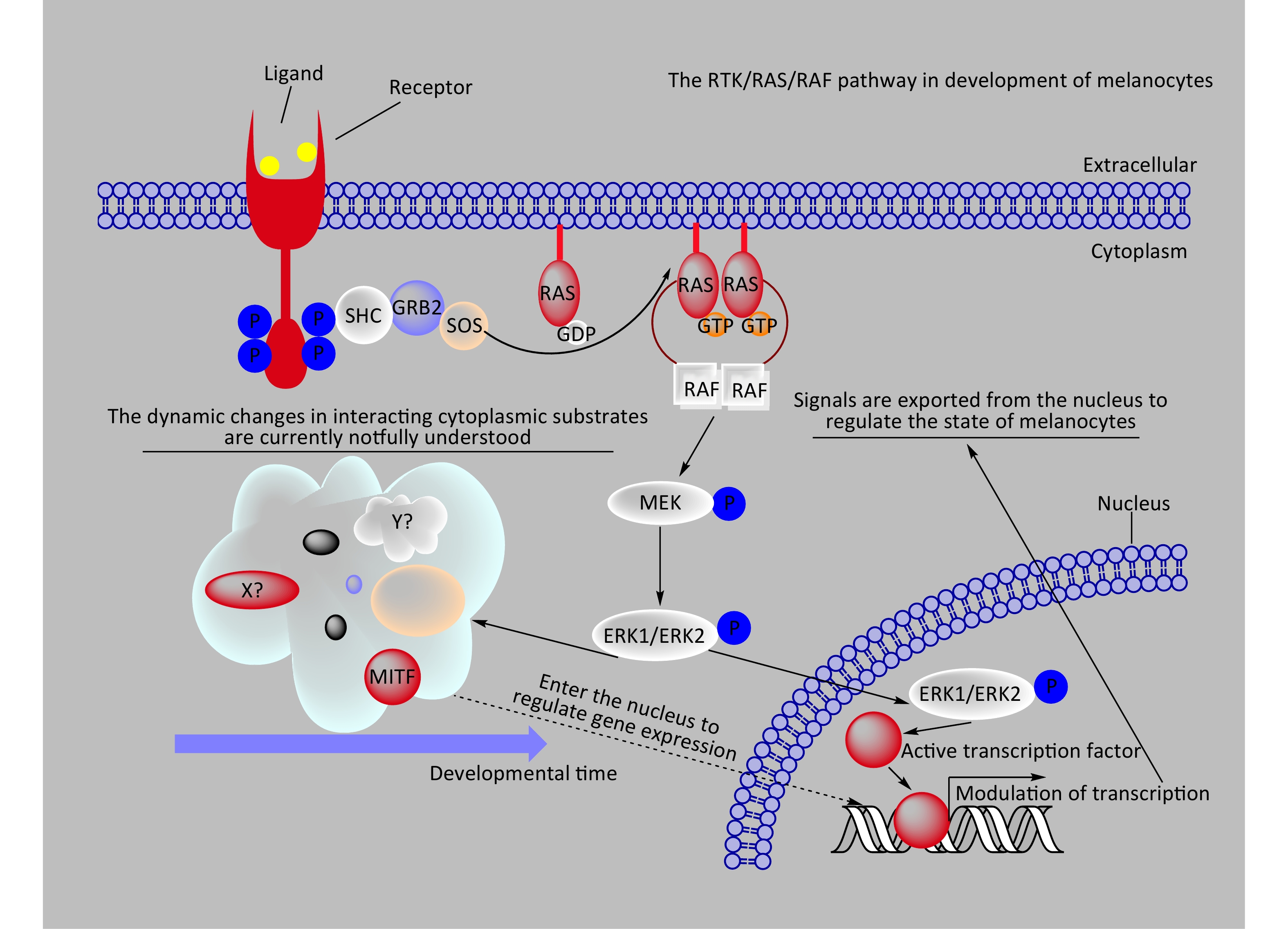

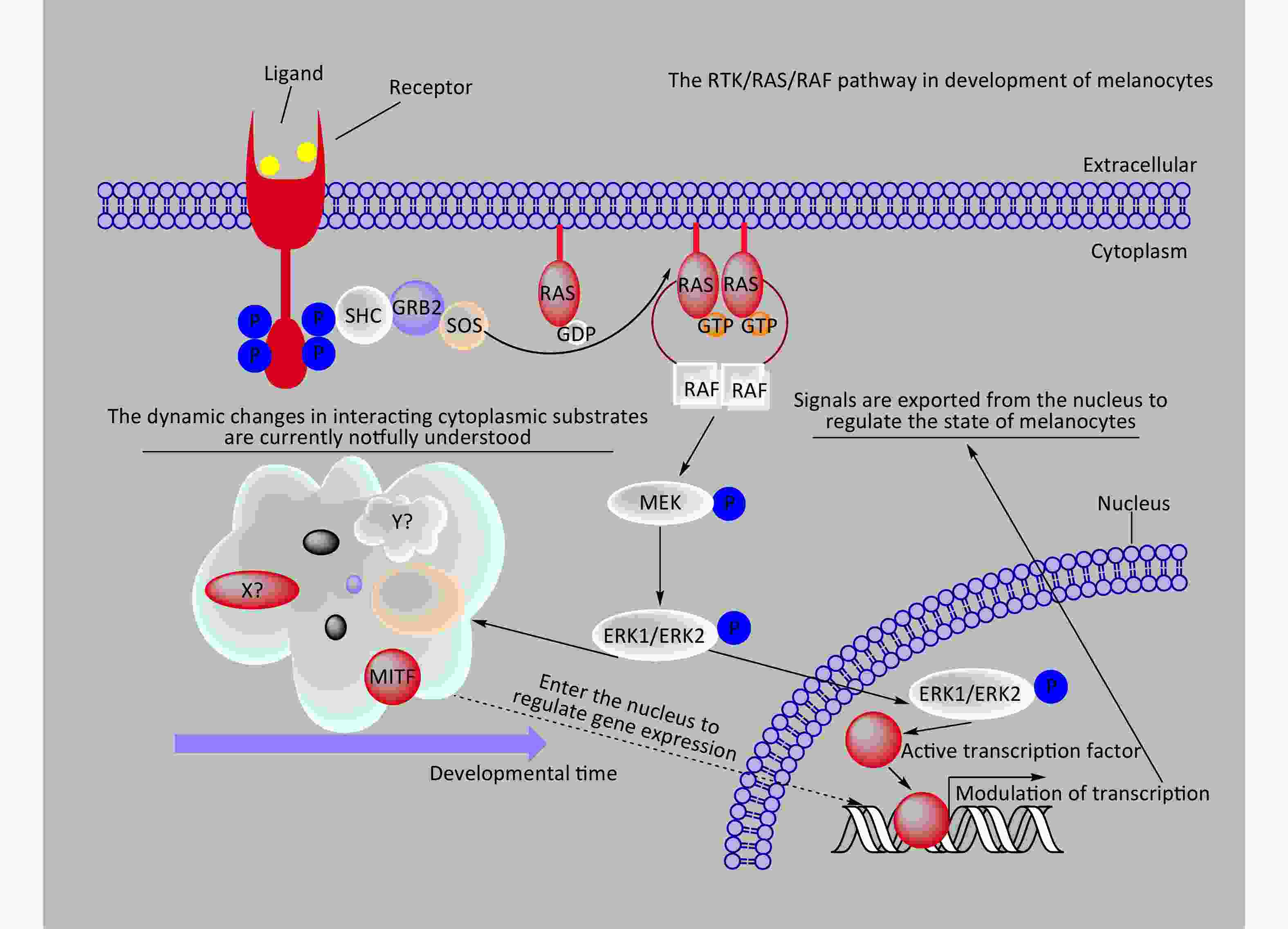

The BRAF/MAPK signaling pathway regulates various cellular processes, including growth, division, differentiation, migration, apoptosis, and aging[43-46]. Under normal physiological conditions, external growth factors or ligands that bind to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) on the cell membrane induce conformational changes in the RTKs, activating their kinase activity through phosphorylation[47] (Figure 3). Phosphorylated RTKs create binding sites for interaction with RAS proteins located on the inner side of the cell membrane, triggering the conversion of RAS from a GDP-bound state (RAS-GDP) to a GTP-bound state (RAS-GTP)[46,48]. RAS-GTP, the active form of RAS, recruits BRAF to interact with RAS-GTP, activating BRAF[32,46]. Among the RAF family members, only BRAF relies on RAS for its activation under normal circumstances[49]. Activated BRAF phosphorylates and activates two MEK proteins, which subsequently phosphorylate and activate ERK1/2[46]. Once activated, ERK1/2 can directly phosphorylate cytoplasmic substrates to regulate downstream molecules or translocate to the nucleus to phosphorylate transcription factors, triggering their ubiquitination, degradation, and direct modulation of downstream gene expression to control cellular states[46,50].

Figure 3. A schematic diagram provides a concise representation of the role of the RTK/RAS/RAF/ERK signaling pathway in melanocyte development. In the diagram, X? and Y? represent unknown substrates in the cytoplasm that interact with phosphorylated ERK1/2. RAF, rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; MEK, mitogen-activated proteinkinase kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activatedprotein kinase..

In 2002, the presence of BRAFV600E was observed in various human tumors, such as certain lung, thyroid, and colorectal cancers and melanoma, all of which led to sustained activation of the MAPK signaling pathway[51]. Subsequently, in 2003, it was found to be prevalent in most nevi[12]. Substantial evidence has confirmed that approximately 80% of nevi carry the BRAFV600E mutation[9]. In 2005, Michaloglou et al. demonstrated that expressing BRAFV600E in cultured melanocytes induced oncogene-induced senescence (OIS), as evidenced by the expression of OIS markers (p16INK4A and senescence-associated beta-galactosidase)[11]. Furthermore, congenital melanocytic nevi carrying the BRAFV600E mutation exhibited positive staining for p16INK4A and senescence-associated beta-galactosidase[11]. This study confirmed the occurrence of BRAFV600E-induced OIS and provided an explanation for nevus formation[11,52]. Specifically, the BRAFV600E mutation in melanocytes triggers aberrant proliferation followed by entry into a senescent state, culminating in nevus formation[11,52]. The entry of BRAFV600E-mutated melanocytes into a senescent state after proliferation serves as a strategic mechanism to impede the progression of melanoma cells[53]. This strategy explains why the vast majority of nevi do not progress to malignant melanoma despite their prevalence in nearly all individuals. For a more detailed understanding of the dynamic process underlying BRAFV600E-induced growth arrest in melanocytes, we recommend consulting additional well-regarded reviews[18,54,55].

During melanocyte development, phosphorylated ERK1/2 directly phosphorylates microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) at Ser73 or activates p90/RSK, which subsequently phosphorylates Ser409 of MITF[56]. Phosphorylated MITF undergoes degradation or recruits p300/CBP transcription factors to enhance its activity, thereby regulating the expression of downstream target genes and governing crucial aspects of melanocyte biology, including proliferation, differentiation, and survival[57-59]. In the differentiation, migration, survival, and maturation of neural crest cells into mature melanocytes, external signals (growth factors or ligands) activate RTKs like Kit, triggering the MAPK signaling pathway[58,60-62]. In such a microenvironment, the dynamic profiles of relevant RTKs, cytoplasmic substrates phosphorylated by ERK1/2, and nuclear substrates phosphorylated by ERK1/2 are closely associated with adult melanocyte-related disease occurrence. However, these dynamic profiles were limited.

-

Upon BRAFV600E mutation in melanocytes, continuous phosphorylation of MEK1/2 occurs, leading to the subsequent phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2. Sustained ERK1/2 activation triggers the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and DNA damage, thereby activating the MKK3/6-p38 signaling pathway and inducing OIS[50,63,64]. Moreover, sustained ERK1/2 activation can directly activate AP-1 and ETS transcription factors, which regulate the p38δ signaling pathway and contribute to OIS[65]. Among the p38 isoforms, p38δ is a distinct isoform in the MKK3/6-p38 pathway, regulated by phosphorylated ERK1/2-responsive AP-1 and ETS transcription factors[66]. Additionally, two other p38 isoforms, p38α and p38γ, mediate OIS through distinct mechanisms[65,66]. Specifically, p38α phosphorylates serine 401 of the HBP1 transcription factor, activating p16INK4A. Additionally, p38α can phosphorylate threonine 182 of RPAK, leading to p53 activation by phosphorylating serine 37 of p53. p38γ mediates serine 33 phosphorylation of p53, resulting in its activation. Upon activation, p53 induces the expression of its target genes, including p21WAF1, in collaboration with p16INK4a to regulate the cell cycle and trigger OIS. p38δ-mediated OIS operates independently of the p53 and p16INK4a signaling pathways. Instead, it is potentially initiated through the DNA damage response mediated by the checkpoint kinases CHK1/CHK2. Nevertheless, the expression of p53, p21, and p16INK4a exhibits significant heterogeneity in the melanocytes of some nevi[67]. This heterogeneity suggests the involvement of additional factors in regulating BRAFV600E-induced nevi.

The transcription factor MITF plays crucial roles in various physiological processes in melanocytes, including lineage determination, differentiation, migration, and maturation. For more details, please refer to other excellent review articles[68-70]. The MITFE318K mutation in humans is associated with susceptibility to nevi and melanoma[71,72]. However, significant nevi-related phenotypes are not observed in MitfE318K mice[73]. Nonetheless, the presence of MitfE318K increases the incidence of spontaneous nevi formation in BRAFV600E mice[73]. This suggests that the mutation in MITF SUMOylation site 318 enables interaction with the BRAFV600E/MAPK signaling pathway, thereby promoting nevi formation[74]. However, the precise molecular mechanism governing the interplay between the MITFE318K and BRAFV600E/MAPK pathway interplay remains elusive, and there are no reports on their interaction in other animal models[74]. In diverse cellular contexts, the BRAF/MAPK signaling pathway can phosphorylate MITF via activated ERK1/2, leading to proteasome-mediated degradation or enhancing MITF activity by recruiting p300/CBP transcription factors[57-59]. Furthermore, the BRAF/MAPK pathway can synergistically phosphorylate MITF with downstream molecules such as GSK3 in the PI3K and WNT signaling pathways through activated ERK1/2. This process regulates the nuclear and cytoplasmic distribution ratio of MITF, thereby controlling the activity of MITF to regulate the state and fate of melanocytes or melanoma cells[59,75,76]. Activation of ERK1/2 by the BRAF/MAPK pathway also phosphorylates MITF, thereby regulating the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and inducing G1 cell cycle arrest in melanocytes, which is consistent with the observed expression of the OIS marker p16INK4a in nevi[61]. Given the complexity of the regulatory network of MITF and its downstream target genes and its paramount importance in melanocytes[70], a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism underlying the induction of OIS by the BRAF/MAPK signaling pathway remains to be elucidated.

In addition to inducing OIS and mediating nevi formation through p53-, p16INK4a, and MITF-related signaling pathways, various other factors regulate the proliferation and aging of BRAFV600E-mutated melanocytes, contributing to nevus development. ERK1/2 activity within the BRAF/MAPK pathway dynamically governs the proliferation and differentiation of BRAFV600E-expressing melanocytes by activating distinct downstream signaling pathways[77]. Similarly, the MITF/AXL/BRN2 pathway fluctuates during melanoma occurrence and progression, resulting in diverse cellular states and behaviors[68,76,78,79]. However, the reasons for fluctuations in ERK1/2 activity during nevus formation, the dynamic spectrum of its consequences, and its potential interplay with the MITF network in nevus regulation remain to be elucidated. It is noteworthy that melanocytes in nevi are perpetually in a state of cell cycle arrest, according to the definition of cellular senescence definition[80-82]. However, melanocytes in the nevi can re-enter the cell cycle or continue to proliferate to form melanoma cells[13]. Classic senescence markers (Table 1), such as p16INK4a, p53, H2AX, and beta-galactosidase, exhibit significant heterogeneity in nevi and may not effectively distinguish between nevi and melanoma[83]. Consequently, some research challenges the OIS theory of BRAFV600E-induced nevus formation, highlighting the need to further elucidate the complex mechanisms involved[13,67,83].

Conception[84] Cellular senescencea Cell type[80] Senescent cells encompass diverse cell types, with a notable prevalence of replication-competent cells, such as endothelial cells and melanocytes. Growth arrest[85,86] Permanent cell cycle arrest

Cell growth arrest refers to a state in which cells stop dividing and become inactive under certain conditions. This can be caused by factors such as cellular aging, contact inhibition, nutrient deficiency, or DNA damage. Growth arrest plays an important role in maintaining tissue homeostasis and preventing diseases.Metabolism[85] High DNA content[80,85] 2N or 4N Effectors[80,84] p16INK4a, p21WAF1/CIP1 (also known as p21), ARF, p53, and RB Markers[80,84,87-93] Cell cycle arrest: Brdu ↓, Edu ↓ (Lack of DNA synthesis), Ki67 ↓, C-MYC ↓, PCNA ↓ (Lack of proliferation), p16INK4a ↑, pRB ↑, p15 INK4b ↑, p27 ↑, phosphor-pRb ↓ (Activation of p16-pRB axis), p21 ↑, p53 ↑, phospho-p53 ↑, DEC1 (BHLHB2, also known as TNFRSF10C) ↑, PPP1A ↑ (Activation of p53-p21 axis).

Structural changes: Enlarged, flattened, and irregular morphology, vacuolized, occasionally multinucleated (Morphology, cell size), SA-β galactosidase ↑, SA-α-Fucosidase ↑, Lipofuscin ↑, LysoTrackers ↑, orange acridine ↑ (Increased lysosomal content and activity), γH2AX ↑, 53BP1 ↑, Rad17 ↑, ATR ↑, ATM ↑, MDC1 ↑, TIF ↑ (DNA damage), ROS ↑ (ROS), Telomere ↓(Telomere shortening), DAPI/Hoechst 33342 ↑, HIRA ↑, H3K9-methylation ↑, PML bodies ↑, HP1γ ↑ (Senescence associated heterochromatin foci formation), Lamin B1 ○/↓ (Nuclear membrane).

NF-κB signaling: TNF ↑, CXCL1 ↑, IL-6 ↑, VEGF ↑, iNOS ↑, COX-2 ↑, E-selectin ↑, MIP2 ↑, RANTES ↑, Survivin ↑, XIAP ↑, BMP-2 ↑ (Increased NF-κB activation).

Mitochondria: Mitotrackers ↑ (Accumulation of mitochondria), IL-10 ↑, CCL-27 ↑, TNF-α ↑ (Mitochondrial dysfunctional associated senescence).

Pro-survival: Annexin V ○, Cleaved PARP ○, Cleaved caspase 2/3/9 ○, TUNEL staining ○, Bcl-2 ↑, Bcl-w ↑, Bcl-xL ↑ (Apoptosis exclusion).

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype: IL-1a ↑, CCL2 ↑, IL-6 ↑, IL-8 ↑, CXCR2 ↑, IGF1 ↑, PAI1 ↑, IGF2 ↑, IGFBP3 ↑, IGFBP5 ↑, IGFBP7 ↑, STC1 ↑, GDF15 ↑, SERPINs ↑, MMP1 ↑, MMP3 ↑, VEGF ↑ (Cytokine secretion), TGFβ ↑, IFN-γ ↑, BLC↑, MIF ↑ (Inflammatory molecules).

Others: ICAM-1 ↑, DEP1 ↑, B2MG ↑, NOTCH3 ↑, DCR2 (TNFRSF10D) ↑, Caveolin-1 ↑, Vimentin ↑, DPP4 ↑ (Plasma membrane protein expression), FBXO31 ↑, miR-203 ↑ (Senescence induction).Note. ↑ Represents an increase in staining intensity or upregulation in protein or mRNA detection. ↓ Represents a decrease in staining intensity or downregulation in protein or mRNA detection. ○ represents staining disappearance or a decrease to zero expression in staining or protein/mRNA detection. Bold italicized text indicates markers that can be specifically used to detect oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). aCellular senescence is an enduring state of irreversible cell cycle arrest triggered by diverse deleterious stimuli. Table 1. Cellular senescence

Despite extensive investigations into BRAFV600E-induced nevi formation across multiple disciplines, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenetics, several unresolved issues persist in comprehending the seemingly straightforward transition from abnormal melanocyte proliferation to reversible growth arrest[9,94-104]. Although phosphorylated ERK1/2 plays a pivotal role in nevi formation, the intricate protein network interactions involving phosphorylated ERK1/2 in the nucleus and cytoplasm during nevi development need further clarification[13,105]. Dynamic changes in gene regulatory networks resulting from alterations in protein interaction networks remain poorly understood. Approximately 70% of human nevi maintain their nevus state without progression to melanoma, although changes in size and shape occur, implying a degree of proliferation and growth even in proliferatively arrested nevus melanocytes[106]. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms governing this phenomenon remain unclear. Tg(mitfa:BRAFV600E) zebrafish have been observed to spontaneously develop nevi without progressing to melanoma, rendering them valuable animal models for deciphering the molecular mechanisms involved in this process[5].

-

Numerous mutations drive the development of nevi and melanoma. However, research on BRAFV600E driving nevi and melanoma has been the most extensive. For information on melanoma driver mutations, refer to other excellent reviews for a comprehensive understanding[107]. Currently, in animal models of BRAFV600E-induced nevi, the focus is mainly on mice and zebrafish[5,6,21,25]. Divergent melanocyte-related phenotypes are observed between these models concerning BRAFV600E-induced melanocyte senescence in the nevi. In mice, BRAFV600E can prompt the transformation of melanocytes into nevi, progressing further into melanoma[108,109]. Conversely, in zebrafish, BRAFV600E only triggers nevus formation in melanocytes[110]. The underlying mechanisms accounting for these phenotypic disparities remain elusive and possibly stem from variations in BRAFV600E expression or interspecies distinctions. In mice, low BRAFV600E expression solely results in melanocyte nevi formation, whereas higher expression levels induce melanocyte development into melanoma[108,109]. Species-specific differences are exemplified by humans with TP53 loss-of-function mutations predisposed to diverse tumors, including spontaneously formed nevi and melanomas[111]. In contrast, mice lacking Trp53 do not spontaneously develop nevi or melanomas, whereas zebrafish lacking tp53 show an extremely low incidence of nevi and melanomas[110,111]. However, Xenopus tropicalis lacking tp53 has a higher incidence of nevi and melanomas (approximately 20%)[111]. These findings highlight the varying degrees of fidelity in recapitulating the human disease development process owing to the different animal models and expression levels of gene products. Consequently, employing diverse animal models demonstrating BRAFV600E-induced melanocyte senescence in nevi is imperative for comprehensively elucidating the underlying mechanisms[5].

All animal models pertaining to BRAFV600E extensively rely on exogenous promoters to induce the expression of either exogenous or endogenous BRAFV600E[5,6,21,25]. Although these strategies shed light on disease progression instigated by BRAFV600E under physiological conditions, they fail to circumvent the drawbacks associated with the incomplete specificity of BRAFV600E expression driven by exogenous promoters, Cre leakage, and the need for cautious interpretation of the genotype-phenotype correlation in transgenic BRAFV600E models. To comprehensively unravel the pathogenic mechanisms of BRAFV600E-related diseases, more precise animal models with refined BRAFV600E expression are imperative. Unfortunately, to date, no animal model exists fully driven by endogenous promoters and displays cell-specific expression of BRAFV600E. Such a model, where BRAFV600E is targeted for integration and driven by cell-specific promoters, is indispensable for thoroughly understanding this disease.

Hence, by leveraging gene editing techniques, such as CRISPR/Cas9 and prime editing, it is feasible to drive the specific exogenous expression of BRAFV600E through endogenous promoters in melanocytes within model animals[112]. Alternatively, prime editing enables the introduction of cell-specific point mutations in melanocytes, facilitating the study of cellular state changes resulting from BRAFV600E mutations in vivo at the physiological level[113]. Moreover, CRISPR/Cas9 or CASTs technology enables the endogenous labeling of ERK1/2 with markers, such as APEX2 or BioID[114,115], facilitating the exploration of dynamic alterations in substrates within the cytoplasm and nucleus that interact with phosphorylated ERK1/2 during nevus formation. In summary, constructing animal models with cell-specific BRAFV600E expression using gene-targeting integration strategies, along with integrating protein proximity labeling[115] and multi-omics techniques[116], offers an enhanced understanding of nevus formation. For the treatment of melanoma, inhibitors related to the sustained activation of BRAF mutations and the MAPK signaling pathway have always been research priorities. Therefore, excellent review articles on inhibitors of BRAFV600E and the MAPK signaling pathway have been published[117,118]. These aspects can be explored in detail by referring to the aforementioned studies.

-

Herein, we discuss BRAFV600E-mediated melanocyte nevus formation in animal models and propose gene editing to construct models with cell-specific BRAFV600E expression to study nevus mechanisms. In summary, our first suggestion is to diversify animal models of BRAFV600E-mediated melanocytic nevus formation to complement existing models, thereby providing a more comprehensive range of models necessary for studying the mechanisms involved. Second, by employing gene editing techniques to endogenously label ERK1/2 with markers, such as APEX2 or BioID, we can investigate the dynamic changes in proteins that interact with phosphorylated ERK1/2. This approach reveals the molecular mechanisms responsible for the differential activation spectrum of targets resulting from distinct ERK1/2 activity states and provides a precise and comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms. Unveiling the intricacies of BRAFV600E-mediated melanocyte senescence and nevus formation using novel animal models and technologies will lead to new discoveries and potentially offer innovative strategies for treating BRAFV600E-related human diseases.

HTML

23321+Supplementary Materials.pdf

23321+Supplementary Materials.pdf

|

|

Quick Links

Quick Links

DownLoad:

DownLoad: