-

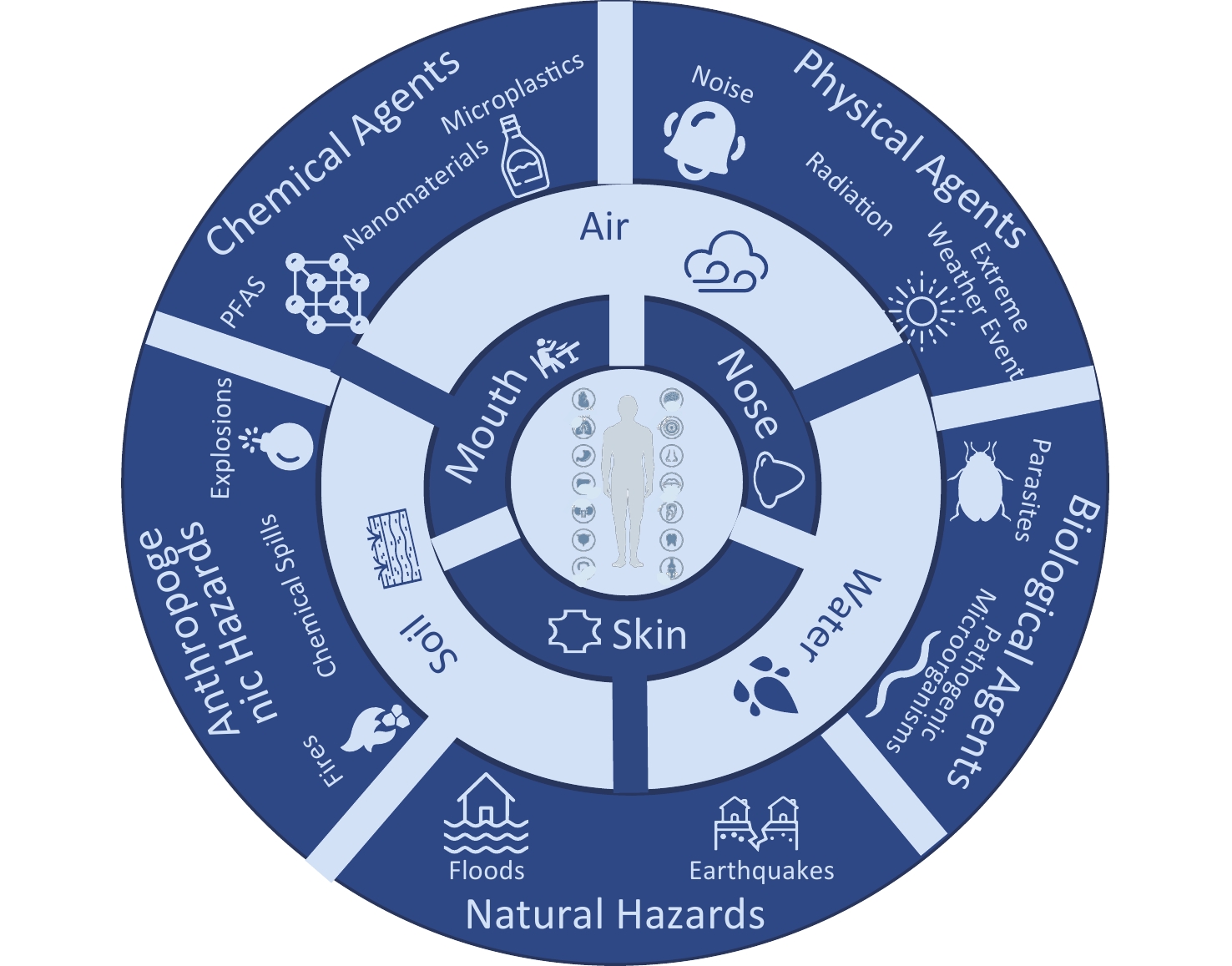

Contemporary human living environments present complex and pervasive health risks, and environmental health challenges are becoming increasingly prominent. These risks encompass diverse domains, such as chemical factors (e.g., heavy metals, nanomaterials, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), physical factors (e.g., noise, radiation, and extreme weather) biological factors (e.g., pathogenic microorganisms and parasites), natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes and floods), and anthropogenic incidents (e.g., chemical spills, fires, and explosions). The complex interplay among these multifaceted hazards poses significant threats to human health, heightening the urgency for comprehensive risk assessment and management (Figure 1)[1,2]. Environmental health risk assessment (EHRA) serves as a pivotal tool for systematically evaluating exposure levels, quantifying health risks, thereby identifying high-risk zones and vulnerable populations, and providing scientific support for the “early identification” and “preemptive intervention” of environmental hazards[3]. Systematic innovation in risk assessment technologies is essential to advance health risk governance[4].

For a considerable length of time, the international community has prioritized EHRA as a core enabler of environmental health management. Since the 1930s, global efforts have evolved from qualitative and quantitative evaluations of acute chemical toxicity to sophisticated assessments of the health impacts of exposure to environmental pollutants[5,6]. Following the 1970s, the establishment of the International Program on Chemical Safety (IPCS) marked the systematization of risk assessment methodologies. Furthermore, International conventions such as the Montreal Protocol and Stockholm Convention, which is grounded in risk assessment science, facilitated precise identification of ozone-depleting substances and persistent organic pollutants (POPs)[7,8]. Recent advancements in computational toxicology, artificial intelligence (AI), and geographic information systems (GIS) have transformed risk assessment paradigms. The integration of these technologies enables multidimensional analyses spanning molecular toxicological mechanisms to population-level exposure dynamics, significantly enhancing the precision and sophistication of health risk assessment technologies [9,10].

For China, establishing a robust environmental health risk assessment technological framework (EHRATF) is pivotal for realizing the national strategies of a Healthy China and Beautiful China. The Report of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China explicitly prioritizes “advancing the Healthy China initiative,” and the Emerging Contaminants Management Action Plan positions risk assessment as a core mechanism for risk mitigation. Furthermore, the 14th Five-Year Plan designates “risk assessment” as a critical tool for reforming the disease prevention and control system[11,12]. However, China’s EHRATF system has systemic deficiencies. First, the existing technological framework remains fragmented, with an overreliance on international methodologies in certain domains and insufficient localized adaptation to China’s unique environmental and demographic contexts. Second, the foundational data infrastructure is underdeveloped and characterized by incomplete exposure parameter databases, inadequate toxicological databases, and fragmented health effect surveillance systems, which collectively undermine evidence-based risk quantification. Third, the adoption of emerging technologies such as biomonitoring, AI-driven predictive models, and high-throughput toxicity screening constrains the cutting-edge capabilities and accuracy of risk identification methodologies.

Therefore, this study aimed to systematically review the evolutionary trajectory of the EHRATF, both domestically and internationally, with focused analysis of bottlenecks and deficiencies in China’s guideline frameworks, data infrastructure, and technological innovation. Through a comparative analysis of global best practices and localized implementations in China, we propose a vision for constructing a scientific, efficient, and China-specific EHRATF. This framework seeks to provide theoretical underpinnings and practical references to advance the Healthy China initiative.

-

During the 1970s, industrialized nations faced severe environmental pollution crises, such as the Love Canal toxic waste landfill incident in the United States of America (USA) in 1978, Minamata disease (mercury poisoning) in Japan, and Yusho rice bran oil poisoning, which highlighted the severe threats posed by pollutants to public health[13]. At that time, no unified EHRA methodology existed globally. Chemical toxicity mechanisms, population exposure parameters, and foundational data remain critically limited, leading to risk assessments that often rely on empirical judgments rather than on quantitative standards or systematic frameworks. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) faced scrutiny of allegations of “political prioritization over scientific rigor,” culminating in its defeat in the 1980 Benzene Standard Environmental Litigation Case[14]. To enhance decision-making scientific validity, the U.S. National Research Council (NRC) published Risk Assessment in the Federal Government: Managing the Process (1983), followed by the EPA’s adoption of this framework in its 1984 report Risk Assessment and Risk Management: A Framework for Decision-Making[15,16]. These documents established a four-step risk assessment paradigm (hazard identification, dose-response assessment, exposure assessment, and risk characterization), marking the world’s first standardized EHRA protocol. Furthermore, Japan developed its hazard-exposure matrix-based hierarchical assessment system for chemicals[17], and the European Union (EU) promoted the 3R principles (replacement, reduction, and refinement) to advance alternative testing methods, reduce animal experimentation, and integrate in-vitro toxicology into risk assessment practices[18].

Despite these advancements, early EHRA frameworks remained largely conceptual and lacked systematic technical standards for integrating hazard exposure and toxicity data into quantitative risk outputs. To address this gap, nations began constructing exposure and toxicity databases to support pollutant risk evaluations, such as the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS), a peer-reviewed repository of chemical toxicity thresholds, carcinogenic slope factors, and research reports, ensuring transparency through multistage expert reviews and public consultations[19]. Japan has initiated chemical substance screening under the Chemical Substances Control Law (CSCL), and has accumulated foundational toxicity data[17]. The EU established the European Inventory of Existing Commercial Chemical Substances (EINECS), which enables systematic chemical risk assessment and regulation[20]. International organizations have also contributed to data standardization and harmonization, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) developed a chemical carcinogenicity classification database[21]. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) formed the Chemicals Testing Working Group and published standardized protocols, such as the OECD Test Guideline 401 (Acute Oral Toxicity), to unify toxicity testing methodologies[22]. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) created an International Register of Potentially Toxic Chemicals (IRPTC), pioneering cross-border data sharing for chemical risk management[23].

-

The rapid globalization of industrial activities during the 1990s and 2010s, coupled with the transboundary migration of emerging contaminants such as electronic waste and POPs, necessitated a paradigm shift toward a globalized and standardized EHRA. To address these challenges, nations have prioritized chemical life-cycle management and refined their technical systems. The U.S. EPA spearheaded this evolution by issuing comprehensive risk assessment guidelines tailored to diverse pollutants (e.g., nanomaterials and pesticides), toxicity endpoints (e.g., carcinogenicity and developmental toxicity), environmental media (e.g., soil and water), and vulnerable populations (e.g., children and women), as well as specific evaluation methods (e.g., exposure parameters, benchmark doses, and cumulative risk assessment), establishing a granular, sector-specific EHRATF[24] (Table 1). Simultaneously, Japan revised its Chemical Substances Control Law (2003) by introducing a risk-based Priority Assessment Substance List and integrating ecotoxicological models to regulate chemical mixtures and emerging contaminants[25]. The EU’s Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) Regulation (2006) marked a milestone by mandating industry-submitted Chemical Safety Reports and pioneering tools, such as exposure scenarios and derived no-effect levels (DNELs), institutionalizing life-cycle risk quantification[26,27].

Category China United States of America Europe Parameter category Exposure Factors Handbook for Chinese Populations (Adult Volume) (2014)

Exposure Factors Handbook for Chinese Populations (Children’s Volume) (2016)Reference Dose (RfD): Description and Use in Health Risk Assessments 1993

Use of the Benchmark Dose Approach in Health Risk Assessment, 1995

Guide to Current Literature on Exposure Factor, 1998

Exposure Factors Handbook (2011)− Framework category - diverse populations − Policy on Evaluating Risk to Children (1995)

A Framework for Assessing Health Risk of Environmental Exposures to Children (2006)

Framework for Human Health Risk Assessment to Inform Decision Making (2014)− Framework category - multimedia/

scenariosTechnical Guidelines for Ecological and Environmental Health Risk Assessment – General Principles (HJ 1111—2020) Developing a Tiered Framework for Extrapolation Modeling (2014) Guidelines for Environmental Risk Assessment and Management Green Leaves III (2011) Framework category - multi-hazard factors Framework Guidelines for Technical Methods of Environmental Risk Assessment of Chemical Substances (Trial Implementation) (MEE Solid Waste and Chemicals Division [2019] No. 54)

Framework for Technical Standard System of Environmental Risk Assessment and Management of Chemical Substances (2024)Framework for Assessing Non-Occupational, Non-Dietary (Residential) Exposure to Pesticides (1998)

Framework for Cumulative Risk Assessment (2003)

EPA’s Strategic Plan for Evaluating the Toxicity of Chemicals (2009)EU Risk Assessment Framework (2014)

Establishment of A Concept for Comparative Risk Assessment of Plant Protection Products with Special Focus on the Risks to the Environment (2017)Framework category - multi-health endpoints − Research Plan for Endocrine Disruptors (1998)

Alternate Testing Framework for Classification of Eye Irritation Potential of EPA-Regulated Pesticide Products (2015)− Application category - diverse populations − Guidance on Selecting Age Groups for Monitoring and Assessing Child-Hood Exposures to Environmental Contaminants (2005)

Guide to Considering Children’s Health When Developing EPA Actions: Implementing Executive Order 13,045 and EPA’s Policy on Evaluating Health Risks to Children (2006)

Guidance on Selecting Age Groups for Monitoring and Assessing Childhood Exposures to Environmental Contaminants (2006)

Revised Methods for Worker Risk Assessment (2014)− Application category - multimedia/

scenariosTechnical Guidelines for Risk Assessment of Contaminated Sites (HJ 25.3—2014)

Technical Guidelines for Occupational Health Risk Assessment of Chemical Hazards in Workplaces (GBZ/T 298—2017)

Technical Guidelines for Soil Pollution Risk Assessment of Construction Land (HJ 25.3—2019)

Technical Specifications for Population Health Risk Assessment of Air Pollution (WS/T 666—2019)

Guidelines for Health Risk Assessment of Groundwater Pollution (MEE Soil Division Letter [2019] No. 770)

Technical Guidelines for Regional Environmental Pollution Health Risk Assessment (T/CSES 53—2022)Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS) (1989)

Air Pollution and Health Risk (1991)

Guidelines for Ecological Risk Assessment (1998)

Drinking Water Screening Level Assessment (2000)

EPA Assessment of Risk from Radon in Homes (2003)

Guidance for Evaluating the Bioavailability of Metals in Soils for Use in Human Health Risk Assessment (2007)− Application category - multi-hazard factors Procedures and Methods for Safety Evaluation of Cosmetics (GB 7919—1987)

Guidelines for Hazard Assessment of New Chemical Substances (HJ/T 154—2004)

Technical Specifications for Toxicity Identification of Chemicals (MOH Supervision Notice [2005] No. 272)

Technical Guidelines for Population Exposure Assessment of Environmental Pollutants (HJ 875—2017)

Technical Guidelines for Environmental and Health Exposure Assessment of Chemical Substances (Trial Implementation) (MEE Announcement 2020 No. 69)

Technical Guidelines for Environmental and Health Hazard Assessment of Chemical Substances (Trial Implementation) (MEE Announcement 2020 No. 69)

Technical Guidelines for Environmental and Health Risk Characterization of Chemical Substances (Trial Implementation) (MEE Announcement 2020 No. 69)

Technical Guidelines for Screening Priority Assessment Chemical Substances (HJ 1229—2021)

Technical Guidelines for Environmental Health Risk Assessment of Chemical Substances (WS/T 777—2021)Guidelines for the Health Risk Assessment of Chemical Mixtures (1986)

Provisional Guidance for Quantitative Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (1993)

Guidance on Cumulative Risk Assessment of Pesticides with a Common Mechanism of Toxicity (2002)

Nanotechnology White Paper (2007)

Guideline for Microbial Risk Assessment: Pathogenic Microorganisms with Focus on Food and Water (2012)

Pollinator Risk Assessment Guidance (2018)Initial Assessment of the Hazards and Risks of New Chemicals for Man and the Environment. Part II (1993)

Initial Assessment of the Hazards and Risks of New Chemicals for Man and the Environment. Part III (1994)

Sustainable and Precautionary Risk Assessment and Risk Management of Chemicals (2001)

Contaminated Land: Risk Assessment Approaches for PAHs (2017)

Generic Guidance to Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment for Food and Water (2018)

Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment (updated series) (2008–now)

Guidance for Human Health Risk Assessment for Biocidal Active Substances and Biocidal Products (2015)

Guidance on risk assessment of nanomaterials to be applied in the food and feed chain (2021)

Guideline on the Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) of Medicinal Products for Human Use (2024)Application category - multi-health endpoints − Guidelines for Mutagenicity Risk Assessment (1986)

Guidelines for Developmental Toxicity Risk Assessment (1991)

Guidelines for Reproductive Toxicity Risk Assessment (1996)

Guidelines for Neurotoxicity Risk Assessment (1998)

Handbook for Non-cancer Health Effects Valuation (2000)

Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment (2005)Risk Assessment of Mixtures of Chemical Carcinogens 2010

Chemical Hazards and Poisons Report 2003-2016

The Use of Biomarkers in Carcinogenic Risk Assessment. 2013Application category - exceptional scenarios Technical Guidelines for Environmental Sanitation Emergency Response to Natural Disasters (2019)

Technical Guidelines for Health Risk Assessment of Sudden Water Environmental Incidents (T/CSES 103—2023)

Technical Guidelines for Drinking Water Sanitation and Environmental Hygiene in Flood Disasters (2024)

Technical Guidelines for Post-Flood Epidemic Prevention and Control (2024)− − Basic methodology category - risk identification − Risk Characterization Handbook (2000) − Basic methodology category - exposure assessment Technical Specifications for Environmental and Health Field Surveys – Cross-Sectional Study (HJ 839—2017)

Technical Guidelines for human Exposure Assessment of Environmental Pollutants (HJ 875-2017)

Technical Specifications for Exposure Factor Surveys (HJ 877—2017)

Technical Specifications for Environmental Health Risk Monitoring (T/CSES 53—2022)Estimating Site-Specific Exposure to Contaminants in Indoor Dust (1995)

Sampling Manual for IEUBK Model (1996)

Guidance on Cumulative Risk Assessment: Part 1. Planning & Scoping (1997)

Summary Report for the Workshop on the Relationship Between Exposure Duration and Toxicity (1999)

Summary Report for the Workshop on Issues Associated with Dermal Exposure and Uptake (2000)

Summary Report of the Technical Workshop on Issues Associated with Considering Developmental Changes in Behavior and Anatomy When Assessing Exposure to Children (2001)

Supplemental Guidance for Assessing Susceptibility from Early-Life Exposure to Carcinogens (2005)

Available Information on Assessing Exposure from Pesticides in Food - A User’s Guide (2007)

Scientific and Ethical Approaches to Observational Exposure Studies (SEAOES) (2008)

Scientific and Ethical Approaches for Observational Exposure Studies (2009)

Exposure Factors Handbook (2011)

Standard Operating Procedures for Residential Pesticide Exposure Assessment (2012)

Indirect Dietary Residential Exposure Assessment Model (IDREAM) Implementation (2015)

Occupational Pesticide Handler Exposure Data (2015)

Occupational Pesticide Post-Application Exposure Data (-)

Guidelines for Human Exposure Assessment (2019)Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment: Chapter R.16 Environmental Exposure Estimation (2012)

Guidance on harmonised risk assessment methodologies for combined exposure to multiple chemicals (2019)

Guidance on harmonised methodologies for human health, animal health and ecological risk assessment of combined exposure to multiple chemicals (2020)Basic methodology category - dose-response relationship characterization Toxicological Testing Methods for Pesticide Registration (GB 15670—1995)

Technical Guidelines for Deriving Water Quality Criteria for Human Health (HJ 837-2017)Model Site Conceptual Model for RI/FS Baseline Risk Assessments of Human Health (1995)

PCBs: Cancer Dose-Response Assessment (1996)

Guiding Principles for Monte Carlo Analysis (1997)

Exploration of Aging and Toxic Response (2001)

Acute Oral Toxicity Up-And-Down Procedure (2002)

Advances in Genetic Toxicology and Integration of in Vivo Testing into Standard Repeat Dose Studies (2002)

Potential Implications of Genomics for Regulatory and Risk Assessment Applications at EPA (2004)

Dioxin Toxicity Equivalency Factors (TEFs) for Human Health (2010)

Benchmark Dose Technical Guidance (2012)

Process for Establishing and Implementing Alternative Approaches to Traditional in Vivo Acute Toxicity Studies (2014)Practical guide How to use and report (Q)SARs (2016)

(Q)SAR Assessment Framework: Guidance for the Regulatory Assessment of (Quantitative) Structure − Activity Relationship models (2023)Basic methodology category - risk characterization − Probabilistic Analysis in Risk Assessment (1997)

Risk Characterization Handbook (2000)

Probabilistic Methods to Enhance the Role of Risk Analysis in Decision-Making (External Review Draft) (2009)

Probabilistic Risk Assessment White Paper (2014)Risk Management Capability Assessment Guidelines (2015) Table 1. Comparison of EHRA technical standards/guidelines between China, the United States of America, and Europe

The rapid advancement of chemical technologies during this period drove the proliferation of synthetic chemicals; however, the refinement of technical frameworks failed to address critical challenges in the risk assessment of emerging contaminants. Severe data gaps in human, animal, and in-vitro toxicity studies of these substances have forced existing risk assessment systems to rely on limited experimental datasets, creating a technical bottleneck that hinders alignment with the exponential growth of the chemical industry, particularly in evaluating population-level exposure–toxicity relationships. This gap in evidence has driven the adoption of computational toxicology approaches. The U.S. report Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy (2007) advocated the integration of high-throughput technologies, computational models, and mechanistic toxicology, leading to initiatives such as the ToxCast program and the EPA’s Computational Toxicology Research Program (CompTox), which became a global template for toxicity testing reform[28]. Concurrently, the EU’s REACH Regulation incorporates quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models for predicting the toxicity of uncharacterized chemicals, embedding 3R principles into regulatory frameworks to reduce reliance on animal testing[29]. Parallel efforts have established multinational databases and computational platforms, such as the U.S. ToxCast/Tox21, PubChem, EU’s International Uniform Chemical Information Database (IUCLID), OECD’s eChemPortal, Japan’s Chemical Risk Information Platform (CHRIP), and Germany’s ProTox 2.0, enabling open-source data sharing and fostering interoperable analytical tools[30]. These collaborative advancements underpin the implementation of international agreements such as the Stockholm Convention, catalyzing global coordination in organic pollutant governance.

-

Post-2010, compounding exposure to legacy and emerging contaminants (e.g., nanomaterials and pesticide residues) challenged conventional risk assessment models, necessitating the integration of individual susceptibility variations and gene-environment interactions into evaluation frameworks. In response, nations updated their technical standard frameworks: the EU issued Guidance on Harmonised Risk Assessment Methodologies for Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals (2019), establishing models for cumulative health risk assessment of multi-chemical co-exposures[31], and the U.S. released Guidance for Applying Quantitative Data to Develop Data-Derived Extrapolation Factors (2014), creating a tiered framework leveraging QSAR, in-vitro high-throughput testing, and limited in-vivo data to extrapolate laboratory findings to complex real-world scenarios (e.g., cross-species and multimedia exposures)[32]. Advancements in computational toxicology have intensified the demand for data harmonization and standardization. The EU’s EXPOSOMICS project (2012) integrated genomics and exposomics to unravel complex environment–gene–disease linkages, shifting EHRA from single-pollutant–single-endpoint paradigms to combined exposure models[33]. Under the CompTox program, the U.S. consolidated multinational databases into the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, the world’s largest toxicity data repository, encompassing physicochemical properties, exposure metrics, and in-vivo/in-vitro toxicity data for more than one million chemical substances, serving as a global benchmark for data interoperability. In 2019, the UNEP’s Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) published the Global Chemicals Outlook II: From Legacies to Innovative Solutions (GCOII), establishing shared mechanisms for chemical management tools and methodologies to enhance transnational data connectivity[34].

-

Since 2020, the persistent presence of emerging contaminants such as microplastics, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and antibiotics, which are characterized by high environmental mobility, recalcitrance to degradation, and poorly understood toxicological mechanisms, has posed escalating health risks to humans. Frequent extreme weather events (e.g., heat waves and cold spells) have amplified the complex interplay between environmental pollution and health hazards, driving international efforts to prioritize predictive early warning systems and life-cycle risk governance[35]. The global environmental health monitoring network has expanded significantly: UNEP’s Global Environment Monitoring System for Water (GEMS/Water) integrates data from > 12,370 monitoring sites across > 80 countries[36], and the U.S. Toxics Release Inventory Network (TRI-NET) enables community-level exposure risk alerts for hazardous substances[37]. Visionary initiatives, such as Australia’s proposed global wastewater genomic surveillance network for airborne pathogens, and the World Health Organization’s four-phase health early-warning framework under climate change[38,39], exemplify this paradigm shift. The rise of AI has further elevated risk assessment and early warning capabilities through multimodal data fusion, enabling multidimensional simulations of complex exposure–health interactions[40]. For example, Dutch researchers leveraged open AI (OpenAI) and a chat generative pre-trained transformer (ChatGPT) to streamline the quality control and standardization of microplastic exposure data[41], and German scientists deployed an open-source AI model toxicant reference interface for data extraction and normalization (TRIDENT) to assess chronic aquatic toxicity risks from low-dose, long-term, mixed contaminant exposures[42]. The EU pioneered AI-integrated chemical risk assessment systems in 2020, marking the transition of AI from research to regulatory applications[43]. In predictive modeling, the European EU’s Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) employs machine-learning, deep-learning, and transformer models to prioritize food safety risks based on pathogen profiles (such as Salmonella, aflatoxins, and Listeria)[44], parallel to the U.S.-developed long short-term memory (LSTM)-based systems that predict respiratory disease risks using real-time air pollution and meteorological data[45].

-

Amid the global evolution of EHRA, nations and organizations have developed distinct EHRATF models tailored to their regulatory and technological priorities, with the EU and the U.S. emerging as paradigmatic examples. The EU system is anchored in regulatory integration and tiered assessment principles; whereas, the U.S. framework emphasizes the synergistic coordination of exposure-to-health hazard standardization, technological innovation, and dynamic iterative refinement.

-

The EHRATF is distinguished by its systematic rigor, scientific robustness, and forward-looking adaptability. Anchored in the REACH Regulation and Classification, Labelling, and Packaging Regulation (CLP Regulation), the EU has established standardized protocols such as the EU Risk Assessment Framework (2014), operational guidelines including the Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment (updated series), and specialized directives such as the Guidance on Risk Assessment of Nanomaterials in the Food and Feed Chain (2021) (Table 1). A hallmark innovation is the Weight of Evidence (WoE) methodology, which employs a 137-indicator scoring system to integrate multidisciplinary data and resolve uncertainties in complex exposure assessments. The EU pioneered a five-tiered hierarchical assessment model: Tier 1 utilizes QSAR predictions and read-across techniques for high-risk substance screening[46]; Tier 2 applies threshold of toxicological concern (TTC)-based exposure simulations[47]; Tier 3 employs physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to quantify target organ exposure doses[48]; Tier 4 implements in-vitro high-throughput testing and computational toxicology analyses[49]; and Tier 5 triggers animal testing and epidemiological studies for high-priority substances[50]. This tiered strategy ensures scientific rigor while optimizing cost efficiency and throughput. A dynamic update mechanism further underscores the innovation of the framework. The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) conducts triennial technical reviews to refine methodologies, exemplified by the iterative revisions of the Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment across > 10 editions[51]. Emerging risks, such as microplastic bioaccumulation and climate-sensitive infectious diseases, are proactively integrated into priority lists via initiatives such as the Zero Pollution Action Plan[52]. Projects such as EU-ToxRisk, funded by Horizon 2020, advance New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) as standardized animal-free assessment tools[53]. This finding cements the EU’s leadership in ethical and adaptive risk governance.

-

The U.S. EHRATF prioritizes efficacy maximization through granular standardization, robust data integration, and iterative innovation. Its distinctive features are threefold. First, comprehensive technical standardization is exemplified by > 70 EPA-issued risk assessment guidelines governing full-chain processes from hazard identification to risk characterization (Table 1). For example, pioneering methodologies include the IRIS, which establishes toxicity thresholds via reference doses (RfD) and unit risk values (URV), and the innovative application of benchmark dose (BMD) modeling to refine exposure–response analyses[54,55]. The Landmark Report Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment (2009) redefined carcinogen evaluation by integrating exposure context, mode of action (MOA), and population susceptibility into quantitative toxicity frameworks[56]. Second, biomonitoring and computational toxicology breakthroughs are anchored by the National Biomonitoring Program (NBP) (launched in 1999), which tracks > 400 pollutants (e.g., bisphenol A and PFAS) and health biomarkers across thousands of individuals, creating the world’s largest biomonitoring database[57-59]. The Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy catalyzed systemic transformation, leveraging the ToxCast high-throughput platform for rapid toxicity screening, integrating ExpoCast exposure data with ToxPi models for risk prioritization, and advancing animal-free assessments via the CompTox Chemicals Dashboard[28]. Third, dynamic iterative updates ensure continuous advancement; the EPA revises guidelines to reflect technological progress, periodically updates IRIS with cutting-edge research, and enhances ToxCast with new high-throughput screening data. Through the synergistic coordination of guideline-driven governance, big data platforms, and iterative refinement, the U.S. maintains global leadership in chemical regulation, toxicity prediction, and early risk warning systems.

In summary, the international EHRATF has evolved into a systematic and adaptive system, integrating technical methodologies, data interoperability, and iterative refinement. The current framework is advancing with AI as its pivotal breakthrough, addressing the health risk challenges posed by environmental hazards through innovative technologies such as multimodal data fusion, intelligent algorithms, and next-generation monitoring platforms.

-

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, decades of development have seen China’s EHRATF evolve from reactive industrial pollution management to proactive control of emerging contaminants, achieving foundational progress in localized parameter development and intelligent monitoring technologies.

-

China experienced rapid industrial and agricultural growth from the 1950s–1970s. The 1962 Hygienic Standards for Industrial Enterprise Design (GBJ 1-62) pioneered the setting of the maximum allowable concentrations for 19 hazardous substances in ambient air[60]. Post-1970s, frequent incidents of silicosis and pesticide poisoning linked to industrial pollution, compounded by international lessons learned from public hazards, spurred China’s institutionalization of environmental protection. The First National Environmental Protection Conference in 1973 adopted the “32-Character Guiding Principle” and “the Regulations on Protecting and Improving the Environment”[61], marking the formal inclusion of environmental protection in national governance. Subsequently, under the directive of the former Ministry of Health’s 1978–1985 National Outline for Medical and Health Science and Technology Development, the Institute of Health Sciences under the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences conducted a groundbreaking survey on air pollution and human health across 26 cities covering 50 million people, yielding initial data on urban air pollution levels and population mortality[62]. After 1978, the participation of international programs such as the Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS) for air, water, and biomonitoring enabled domestic scholars to preliminarily adapt models such as the U.S. EPA’s Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS) framework to study environment–disease relationships[63]. Notably, Professor He Xingzhou’s team at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences utilized an exposure–dose–response model to establish, for the first time, that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from indoor coal combustion are the direct cause of elevated lung cancer incidence among women in Xuanwei City, Yunnan Province[64].

-

The former State Environmental Protection Administration issued the Technical Guidelines for Environmental Risk Assessment of Construction Projects (HJ/T 169-2004) in 2004 and formally incorporated a four-step risk assessment framework (hazard identification, dose–response assessment, exposure assessment, and risk characterization) into China’s regulatory system. The 2007 National Action Plan on Environment and Health (2007–2015) signaled a strategic shift from aggregate pollution control towards precise health risk management, concurrently accompanied by increased national investment in integrated public health and environmental pollution governance. During the same year, China initiated the Huai River Basin Environment and Health Survey and Assessment[65], covering 15 counties and cities across 4 provinces within the basin, which amassed extensive data on water quality, soil conditions, ecological parameters, pollution sources, and population health status. Subsequently, commencing in 2010, the National Special Survey on Environment and Health in Key Regions was progressively launched, establishing comprehensive pollution–disease association databases encompassing atmospheric, aquatic, and soil media across > 20 high-risk areas[66]. During this period, the state supported research and development of critical technologies, such as exposure parameters and biomarkers, through national research programs, including the 863 and 973 Programs.

-

In 2014, China issued the Technical Guidelines for Risk Assessment of Contaminated Sites (HJ 25.3—2014), formally incorporating the internationally recognized “four-step framework” (hazard identification, exposure assessment, toxicity assessment, and risk characterization) into the national EHRA system, marking a milestone for contaminated site evaluations. The 2013–2016 release of the Exposure Factors Handbook of the Chinese Population (including separate volumes for children and adults) addressed the gap in exposure parameters in the Chinese population[67,68]. Technologically, the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China have established key research initiatives such as the “National Research Program for Key Issues in Air Pollution Control” and the “Special Program on Environmental Health,” which have propelled research on exposure assessment and population health effects of particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 µm (PM2.5). In 2013, the former National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) launched the National Air Pollution Population Health Monitoring Program. This initiative developed a comprehensive information platform integrating multisource data collection, authorization management, cleaning and verification, built-in quality control, and analytical utilization of monitoring data[69]. The Commission subsequently formulated the Technical Specification for Health Risk Assessment of Population Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution (WS/T 666—2019), thus facilitating the widespread implementation of risk assessment practices.

-

Post-2020, China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) and National Health Commission (NHC) have successively issued key standards, including the Technical Guidelines for Ecological and Environmental Health Risk Assessment – General Principles (HJ 1111—2020) and the Technical Guidelines for Environmental Health Risk Assessment of Chemical Substances (WS/T 777—2021). These are complemented by plans to formulate/revise > 20 supplementary standards, such as the Framework Guidelines for Technical Methods of Environmental Risk Assessment of Chemical Substances (MEE Solid Waste and Chemicals Division [2019] No. 54), which aim to establish a three-tiered technical framework (general principles, basic methods, and application domains) and a full-cycle standard system (screening – assessment – control)[70,71]. These demonstrate China’s ongoing refinement of its technical framework for environmental health risk assessment (Table 1).

China has established the integrated air pollution and climate health monitoring platform spanning 31 provinces and 167 monitoring stations, enabling full-chain data collection, processing, and application[69]; nationwide deployment of heatwave health risk early-warning systems, cold wave health risk prediction models, and Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) forecasting technologies across 27 cities[72,73]; and ongoing development of a municipal wastewater public health risk surveillance platform covering > 120 cities. In 2016, China initiated the China National Human Biomonitoring (CNHBM) project, which monitors > 21,000 people at 152 sites across 31 provinces for 302 chemical substances, with regular updates to the list[74]. Concurrently, by leveraging global insights and AI advancements, Chinese researchers have pioneered innovations in database construction, computational toxicology, high-throughput screening, and multiomics. Notable databases include the Inventory of Existing Chemical Substances in China (IECSC, China/Ministry of Ecology & Environment), the Chemistry Database (China/Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry of CAS), Toxicology Resources for Intelligent Computation (TOXRIC, China/National BioInformation Center), and the Chemical Risk Evaluation and Prediction Software Platform (Dalian University of Technology)[75-78]. AI-driven innovations have catalyzed transformative advances across the EHRA, ranging from multitier QSAR models for toxicity and target affinity prediction[79] to machine-learning algorithms (e.g., deep learning and support vector machine) for nanomaterial toxicity forecasting and groundwater pollution spatiotemporal exposure modeling[80]. These breakthroughs extend to DeepRisk algorithms for genome-wide identification of high-risk individuals[35,81], next-generation computational toxicology frameworks integrating multidimensional data[82], and multi-omics–AI fusion platforms simulating complex environmental exposures and gene-environment interactions[40]. Exemplifying the application of these technologies, the “Jiu’an” AI prediction platform exemplifies the cutting-edge integration of multisource data and intelligent algorithms to enhance chemical accident simulation and early warning capabilities[83]. Collectively, these advancements provide a robust scientific foundation for hazard identification, exposure–response modeling, and dynamic risk surveillance.

-

Based on the aforementioned analysis, we conducted a comparative analysis of domestic and international EHRATFs in terms of technical framework, foundational data, and innovative iteration.

-

Internationally advanced risk assessment systems are distinguished by their systematic and dynamic frameworks, which are characterized by hierarchical and progressive technical architectures alongside modular guideline clusters that enable comprehensive, multidomain, and full-chain coverage. These systems integrate methodologies such as multimedia exposure modeling and cumulative risk assessment, while addressing diverse effect endpoints through scientifically validated approaches. Dynamic update mechanisms ensure continuous technological iteration, fostering collaborative validation of models and data, and deep integration of standards with cutting-edge innovations. For example, in the context of standardized exposure parameter guidelines, the German Reference Exposure Parameter Values (RefXP) encompass categories such as environmental exposure, consumer product usage, and occupational exposure. It provides > 1,500 parameter entries covering the full life cycle (stratified by age group and sex) (https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/en/www.uba.de/refxp). Similarly, the Exposure Factors Source for Europe (ExpoFacts) consolidates > 3,000 parameters, including dietary intake and time–activity patterns. These parameters are stratified according to age (0–75+ years) and sex. Both resources support chemical risk assessments and policy development (https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset/jrc-10114-10001) (Table 1).

In contrast, despite issuing regulations and guidelines for chemical substance screening, hazard/risk characterization, air pollution, land-use scenarios, and natural disasters, China’s EHRATF remains fragmented and underdeveloped. Key shortcomings include: (1) weak standard foundations, marked by absent terminology standards, and lagging standardization of localized parameters (e.g., exposure factors and physiological/metabolic metrics); for example, the currently published Exposure Factors Handbook of the Chinese Population covers categories such as inhalation, drinking water intake, dietary consumption, dermal contact, and time–activity patterns. It contains nearly 2,000 parameters, presented in separate volumes for adults and children[67,68]. However, China’s exposure parameters for sensitive subgroups such as infants, toddlers, and the elderly remain insufficiently systematized, and also exhibit a relative scarcity of parameters specifically addressing occupational exposure behaviors, alongside insufficient granularity in regional and scenario-specific data; (2) ambiguous technical frameworks, with guidelines inadequately covering multidimensional applications (e.g., vulnerable populations, multimedia/multi-scenario exposures, multi-hazard/multi-health endpoints, and emergencies) and lacking full-chain integration; and (3) disjointed methodological infrastructure, evidenced by non-standardized implementation of WoE, combined exposure synergy models, QSAR, and alternative tools (e.g., organ-on-a-chip), coupled with stagnant updates to sector-specific technical guidelines.

-

Internationally advanced systems have established a full-chain assessment infrastructure that integrates monitoring data modelling tools, enabling robust risk evaluation. In population biomonitoring, developed nations leverage standardized biological monitoring networks to accumulate long-term exposure–health effect correlation data, coupled with the integration of dynamic exposure models and multi-source heterogeneous data (environmental, behavioral, and biomarker), forming the foundation for life-cycle-spanning databases. In multidimensional databases, structured knowledge bases are being established to integrate physicochemical properties, exposure parameters, ecological data, and toxicological information. Prominent examples include the US E.P.A.’s CompTox Chemicals Dashboard, encompassing > 1.2 million compounds, and the EU ECHA CHEM database (as of 2025), which contains toxicological data for > 360,000 chemical substances. These databases incorporate dynamic update mechanisms and uncertainty quantification modules that underpin pollutant source identification and toxicity prediction. Furthermore, diverse modeling tools enable user-friendly operations, generate assessment reports compliant with multiple regulatory standards (e.g., REACH, and the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals), and facilitate the clear characterization of risk assessment outcomes. By integrating high-throughput screening (HTS), QSAR models, and in-vitro to in-vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) techniques, these systems enable comprehensive risk simulation and toxicity assessment across the entire continuum, from molecular mechanisms to population-level effects (Table 2).

Database name Country/organization Chemical count Physicochemical data Human exposure data In-vitro/in-vivo toxicity data Direct benchmark dose (BMD) Risk assessment applicability Last updated Website link CompTox Chemicals Dashboard U.S. / EPA 1,218,248 Yes Partial (ExpoCast) Yes Yes Yes 2025 https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/ ZINC20 U.S. / UCSF 23,000,000 Partial No No No No 2024 https://zinc.docking.org/ LINCS U.S. / NIH 1,678,000 (perturbagens) No No Yes (cell-based) No Partial (translational) 2024 https://lincsproject.org/ ToxCast U.S. / EPA ~10,000 (tested) Partial Partial (exposure) Yes (high-throughput) Yes Yes 2023 https://www.epa.gov/comptox-tools/

toxicity-forecasting-toxcastCEBS U.S. / NIEHS ~3,000 (toxicogenomics) Partial Partial Yes No Partial 2022 https://cebs.niehs.nih.gov/cebs MoleculeNet U.S. / Stanford/MIT ~700,000 (benchmarks) Partial No Partial No Partial (ML research) 2021 https://moleculenet.org/ ECHA CHEM EU / ECHA > 360,000

(Fully registered substances)Yes Yes (consumer/

occupational)Yes Yes (DNELs/PNECs derived) Yes (REACH & CLP compliance) 2025 https://chem.echa.europa.eu/ OECD QSAR Toolbox EU / OECD ~ 155,000 Yes No Yes Yes Yes 2024 https://qsartoolbox.org/ Protox 3.0 EU / Germany

Charite University~32,000 (predicted) Yes No Yes (predicted) No Partial 2024 https://tox.charite.de/protox3/ eNanoMapper EU / Consortium > 700 Yes No Partial No Partial 2024 https://www.enanomapper.net/ Toxtree EU / IdeaConsult Ltd. ~10,000 (rules-based) Partial No Yes (SAR) No Yes 2018 https://toxtree.sourceforge.net/ ChEMBL EU / EMBL 2,496,335 Partial No Yes (bioactivity) No Partial (drug) 2025 https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ STITCH EU / EMBL ~500,000 (chemical-protein) Partial No No No No 2016 http://stitch.embl.de/ Leadscope Model Applier EU/UK / Leadscope ~200,000 Yes No Yes No Yes 2025 https://www.instem.com/solutions/

in-silico/leadscope-model-applier/VEGA EU / IT / Mario Negri Institute ~100,000 Yes No Yes Yes Yes 2024 https://www.vegahub.eu/ DrugBank Canada / University of Alberta ~30,000 (drugs) Partial Partial (clinical) Partial No Partial (pharma) 2023 https://go.drugbank.com/ T3DB Canada / University of Alberta 6,577 (toxins) Partial Partial Yes No Partial 2023 http://www.tedb.ca/ Chemistry Database China / Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry of CAS > 100,000 Yes (structural) yes (> 100,000 ADME) Yes (> 1,000 toxicity, eco-data) No Partial (research) Academic Reg., 2025 https://organchem.csdb.cn TOXRIC China / National BioInformation Center 113,720 Yes (structural) No Yes (13 toxicity classes

275 endpoints)No Partial (multi-domain) 2025 https://toxric.bioinforai.tech/home IECSC China / Ministry of Ecology & Environment ~47,000 Yes (basic properties) No No No Partial (regulatory ID) 2025 https://hgt.cirs-group.com/tools/cis/inv/

62aaaae3bc9325535f80a837Hazardous Chemicals Safety Platform China / Ministry of Emergency Management 7,173 Yes No Yes (LD50, carcinogenicity) No Yes (Workplace safety) Partial, 2025 https://whpdj.mem.gov.cn/publicInternet/

chemicalsDataNote. U.S, United States; EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; UCSF, University of California, San Francisco; LINCS, Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures; NIH, National Institutes of Health; CEBS, Chemical Effects in Biological Systems; NIEHS, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; MIT, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; ECHA CHEM, European Chemicals Agency Chemical Database; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; EMBL, European Molecular Biology Laboratory; STITCH, Search Tool for Interactions of Chemicals; VEGA, Virtual models for property Evaluation of chemicals within a Global Architecture; TOXRIC, Toxicology Resources for Intelligent Computation; IECSC, Inventory of Existing Chemical Substances in China. Table 2. Compilation of domestic and international health risk assessment-related databases

In contrast, China’s data infrastructure exhibits systemic gaps. Biomonitoring lacks updated frameworks for pollutants (particularly emerging contaminants), with insufficient integration of exposure models and multi-source data (environmental, behavioral, and biomarker), necessitating enhanced collection and harmonization of low-dose, long-term combined exposure and health outcome data. Regarding databases, domestically developed resources such as the Toxicology Resources for Intelligent Computation (TOXRIC) and Chemistry Databases currently contain registrations for > 100,000 chemical substances. However, the most significant shortcomings of our current databases are the inadequate regulatory acceptance of computational toxicology methods, fragmented data governance, absence of structured knowledge bases and standardized data quality frameworks, incomplete coverage of critical local exposure parameters (e.g., dietary patterns and behavioral factors), insufficient characterization of vulnerable subpopulations, and the fact that key models such as BMD and PBPK still heavily rely on foreign-sourced parameters (Table 2). Model precision and integration remain deficient. Exposure simulation and health effect assessment models lack precision; whereas, real-time monitoring exhibits low integration with machine-learning and QSAR-IVIVE technologies, constraining full-chain risk assessment capabilities.

-

Internationally leading technological frameworks excel in multidimensional integrative innovation: in computational toxicology, QSAR–PBPK–adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) integrated techniques systematically quantify risk transmission pathways and enable cross-model collaborative validation[84]; alternative in-vitro technologies leverage standardized organ-on-a-chip and 3D organoid systems, combined with microfluidic platforms, to simulate multi-organ interactions[85]; multi-omics technologies, underpinned by initiatives such as the Human Early-Life Exposome (HELIX), construct life-cycle-spanning longitudinal multi-omics association models, supported by cloud-based data integration platforms[28]; AI deeply integrates molecular biology and multi-source data to establish dynamic assessment chains for toxicity prediction–exposure assessment–risk early warning[44].

In contrast, China’s technological innovation faces systemic bottlenecks. In computational toxicology, QSAR, AOP, and PBPK models are predominantly applied in isolation, with delayed adoption of model integration and toxicity pathway network construction. 3D in-vitro models and organ-on-a-chip remain exploratory, lacking standardized culture protocols, functional evaluation systems, and cross-platform interoperability mechanisms. Multi-omics data are fragmented across institution-specific repositories, with limited cross-scale integration platforms and standardized analytical workflows. AI-driven toxicity prediction models rely on international open-source training data, which may not align with domestic exposure–health effect profiles. Furthermore, lagging research and development in emerging tools impedes the translation of cutting-edge innovations into practical applications.

In summary, through a comparative analysis between China and international EHRATFs, we found that gaps predominantly manifested in data integration, technological innovation, and standardization capabilities. Developed nations have established systematic frameworks through tiered scientific validation systems, modular technological iteration mechanisms, and deep integration of monitoring–data–model tool ecosystems. However, China faces persistent challenges in technical standard harmonization, multi-source data interoperability, localization of critical parameters, and cross-disciplinary technological convergence.

-

To address the systemic deficiencies in China’s EHRATF, including fragmented technical standards, weak data infrastructure, and lagging methodologies, urgent measures are required to refine full-chain technical standards, integrate smart algorithms and multi-omics technologies, and establish multi-source data platforms, thereby systematically enhancing risk assessment precision and predictive capacity.

-

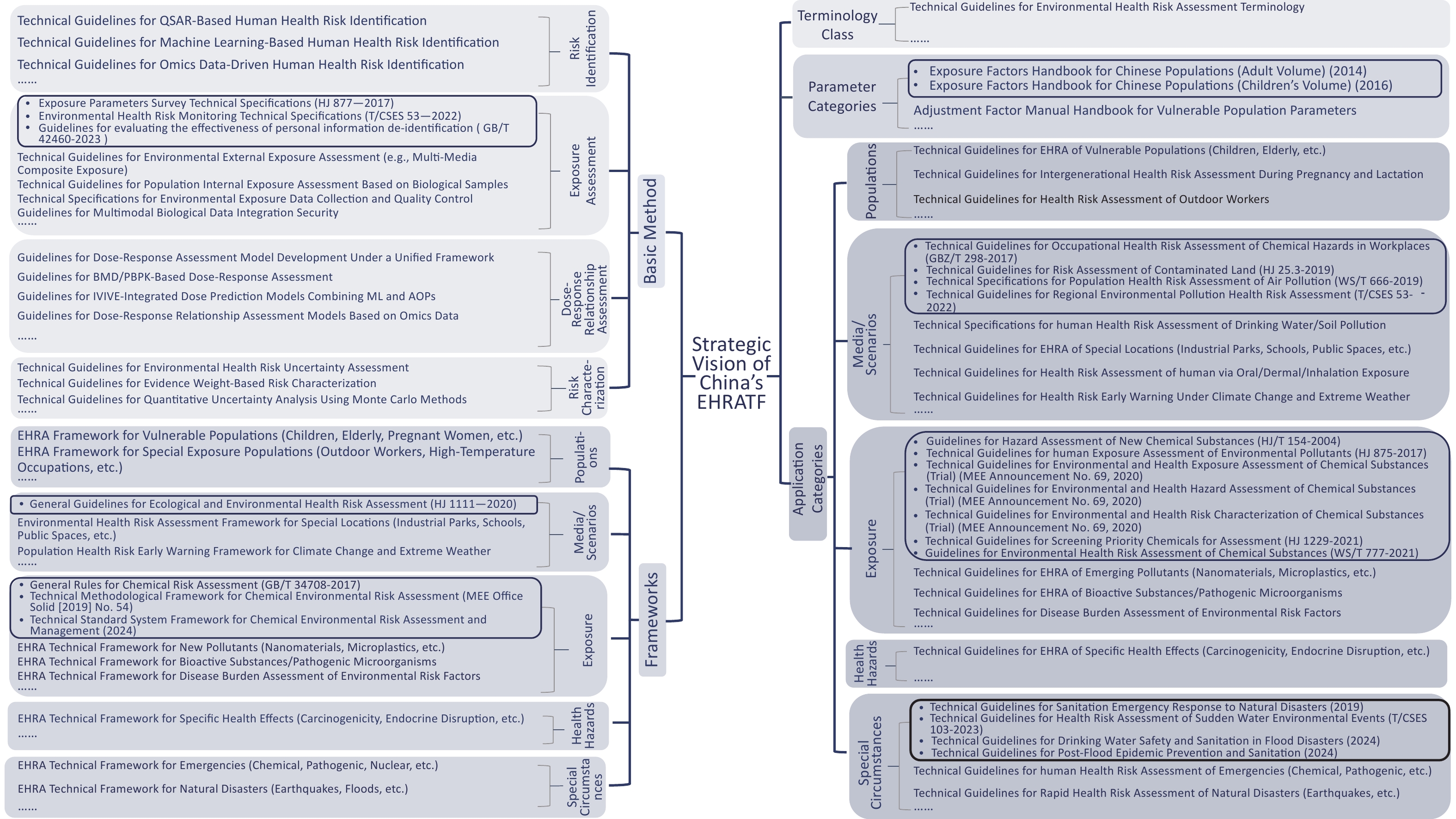

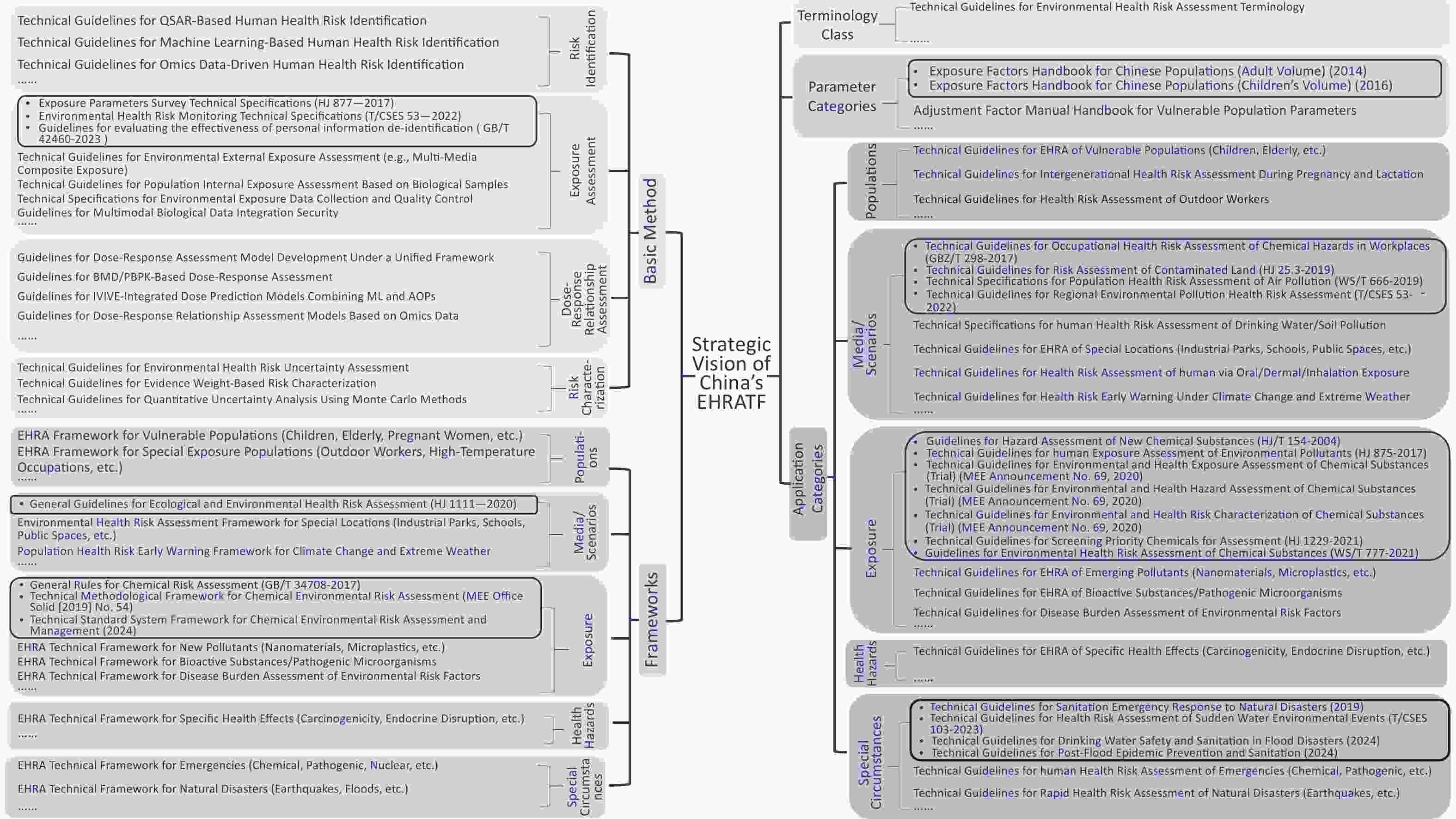

To bridge the gaps in assessing emerging contaminants and combined exposure scenarios, strengthen cross-media coordinated prevention and control for vulnerable populations, and achieve full-chain standardization, China should develop a comprehensive framework supported by five core modules: terminology, parameters, basic methodology, framework, and application-specific standards. Tailored technical documents addressing diverse scenarios should be issued to ensure systematic categorization and multi-tiered coverage, constructing an integrated EHRATF spanning theoretical foundations to practical implementation (Figure 2).

-

To address the critical deficiencies in localized parameter development and lagging assessment methodologies for emerging contaminants, it is imperative to prioritize foundational technical standards. The immediate task involves formulating the “Technical Guidelines for Environmental Health Risk Assessment Terminology” to standardize definitions and classification criteria for core concepts (e.g., “risk characterization,” “endocrine disruption,” and “multimedia combined exposure”), resolving interdisciplinary terminological inconsistencies. Concurrently, localized parameter support must be enhanced through documents such as the “Adjustment Factor Manual Handbook for Vulnerable Population Parameters,” which supplements the existing Exposure Factors Handbook for Chinese Populations to provide scientifically robust data for quantifying exposures in sensitive subgroups. For complex scenario assessments, a multidimensional a framework must be established to provide high-level evaluation pathways, including frameworks for vulnerable populations (children, elderly, and pregnant women) and special exposure groups (outdoor workers) addressing differential susceptibility; frameworks for special sites (industrial zones and schools) and climate-extreme weather early-warning covering multimedia (air, water and soil) and scenario-specific impacts; frameworks for emerging contaminants (nanomaterials and microplastics), bioactive substances/pathogens, and environmental hazard disease burden targeting novel exposure factors; frameworks for specific health endpoints (carcinogenicity and endocrine disruption) focusing on mechanistic pathways (e.g., neurotoxicity); and frameworks for emergencies (chemical, pathogenic, and radiological) and natural disasters (earthquakes and floods) to strengthen rapid response capabilities.

-

To translate frameworks into practice, application-specific guidelines must be developed across dimensions. For populations, “Technical Guidelines for EHRA of Vulnerable Populations (Children, Elderly),” “Technical Guidelines for Intergenerational Health Risk Assessment During Pregnancy and Lactation,” and “Technical Guidelines for Health Risk Assessment of Outdoor Workers” will define physiological parameter models and multi-pathway exposure quantification. For media/scenarios, “Technical Specifications for Human Health Risk Assessment of Drinking Water/Soil Pollution,” “Guidelines for Environmental Health Risk Assessment of Special Sites (Industrial Zones, Schools, Public Spaces),” “Technical Guidelines for Health Risk Assessment via Oral/Dermal/Inhalation Exposure,” and “Technical Guidelines for Health Risk Early-Warning Under Climate Change and Extreme Weather” will standardize media-health effect linkage models, scenario-sensitivity correction factors, and multi-pollutant synergy quantification. For hazard factors, “Technical Guidelines for EHRA of Emerging Pollutants (Nanomaterials, Microplastics, etc.),” “Technical Guidelines for EHRA of Bioactive Substances/Pathogenic Microorganisms,” and “Technical Guidelines for Disease Burden Assessment of Environmental Risk Factors” will specify toxicity identification, multimedia exposure allocation, and health endpoint associations. For health effects, guidelines aligned with frameworks will integrate interdisciplinary evidence to clarify endpoint-specific toxicity pathways. For emergencies, protocols will standardize exposure pathway identification, protection strategies, and secondary effect modeling.

-

Comprehensive methodological packages must include critical assessment stages. For risk identification: “Technical Guidelines for QSAR-Based Human Health Risk Identification,” “Technical Guidelines for Machine Learning-Based Human Health Risk Identification,” and “Technical Guidelines for Omics Data-Driven Human Health Risk Identification” will regulate model extrapolation, feature interpretability, and data quality control. For exposure assessment, “Technical Guidelines for Environmental External Exposure Assessment (Multimedia Combined Exposure)” “Technical Guidelines for Population Internal Exposure Assessment Based on Biological Samples” “Technical Specifications for Environmental Exposure Data Collection and Quality Control” and “Guidelines for Multimodal Biological Data Integration Security” will formalize multimedia migration algorithms, synergy weight factors, biomarker detection protocols, and validation workflows to overcome data fragmentation, model inaccuracies, and scenario gaps, ensuring privacy and data protection. For dose–response relationships, “Guidelines for Dose-Response Assessment Model Development Under a Unified Framework,” “Guidelines for BMD/PBPK-Based Dose-Response Assessment” “Guidelines for IVIVE-Integrated Dose Prediction Models Combining ML and AOPs” and “Guidelines for Dose-Response Relationship Assessment Models Based on Omics Data” will establish validation criteria for molecular initiating events (MIEs), IVIVE workflows, organ-on-a-chip correlations, threshold/non-threshold compound models, and mixture effect prediction. For risk characterization, “Technical Guidelines for Environmental Health Risk Uncertainty Assessment” and “Technical Guidelines for Quantitative Uncertainty Analysis Using Monte Carlo Methods” will mandate probabilistic methods (e.g., Bayesian networks), and the “Technical Guidelines for Evidence Weight-Based Risk Characterization” will set tiered thresholds to enhance the scientific rigor of risk expression.

-

The scientific validity and applicability of the EHRA technological standard system critically depend on the completeness of foundational data, advancement of modeling tools, and systematic integration of technical methodologies. Currently, China faces significant gaps in the accumulation of population exposure–health effect datasets, experimental validation methodologies for toxicity pathways, and multi-source data integration and analytical tools, resulting in persistent bottlenecks such as “data silos” and “tool fragmentation” during the development and implementation of risk assessment standards and guidelines. To address these bottlenecks, three foundational platforms must be prioritized: the population exposure–health effect full-cycle data platform, the toxicity database, and the integrated health risk assessment model toolkit system. This will strengthen the data infrastructure for risk assessment technologies through coordinated advancements in systematic data resource integration, standardized experimental methodologies, and intelligent analytical tools.

-

To advance the construction of population data platforms, it is imperative to establish a national environmental health surveillance network and data-sharing platform encompassing full life-cycle coverage, multimedia exposure, and diverse health outcomes to address critical challenges such as fragmented exposure monitoring datasets and disconnected health effect tracking systems in China. This requires interdepartmental collaboration to standardize full-chain data collection protocols spanning “external environmental exposure data – internal biological monitoring data – health effect outcomes.” Specifically, external exposure datasets must integrate dynamic monitoring data on the spatiotemporal distributions of air and drinking water pollutants, soil heavy metal migration fluxes, and other environmental media metrics, supplemented by wearable device-derived individualized time–activity patterns and microenvironmental exposure concentrations for granular adjustments. Internal biological monitoring data should leverage the biobank infrastructure to standardize detection methodologies for pollutants and metabolites in biological samples (e.g., blood and urine), ensuring data validity while expanding long-term monitoring for the general population, mother–child cohorts, occupational groups, and patients with chronic disease. Health outcome data necessitate interoperability across hospital electronic medical records, mortality surveillance, cancer registries, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-managed infectious/chronic disease databases, and multi-omics datasets (genomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics) to construct molecular epidemiological evidence chains for exposure–gene–disease interactions. Building on this infrastructure, machine-learning-based population health risk assessment and early warning models should be developed, with parallel efforts to establish a multi-source integrated surveillance system tailored to China’s national context for emerging contaminants, climate change, and other globally prioritized domains.

-

The refinement of experimental data platforms must prioritize two objectives: mechanistic toxicity elucidation and parameter localization, addressing technical challenges such as “disconnects in IVIVE evidence chains” and “high uncertainties in cross-species dose-response model extrapolation.” Although international initiatives such as ToxCast and ECHA provide open-access toxicity databases, their reliance on Euro–American physiological parameters and experimental models limits their applicability to China’s risk assessment needs. To resolve this issue, three critical actions are required; first, establishing a localized in-vitro high-throughput screening system targeting high-priority chemicals in China (e.g., PFAS, microplastics, and antibiotics); developing toxicity pathway screening platforms based on organoids and organ-on-a-chip technologies; and creating BMD calculation models aligned with Chinese population cellular sensitivities. Second, strengthen IVIVE technical validation by synchronizing animal experiments with human biomonitoring to build an Asian population-specific correction factor repository for critical parameters (e.g., hepatic microsomal metabolic rates, placental barrier permeability, and dermal absorption coefficients), with an emphasis on toxicokinetic data for vulnerable physiological stages (e.g., childhood development and elderly metabolic decline). Third, advance cross-scale toxicity integration analytics leveraging single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics to decode pollutant-induced cascading effects from MIEs to organelle damage and histopathological alterations, constructing mechanism-oriented risk assessment databases specialized in endocrine disruption, neurodevelopmental toxicity, and other priority endpoints. Furthermore, we implemented a toxicity data quality evaluation system to ensure the traceability, comparability, and reusability of the datasets.

-

Advancements in analytical models and tool platforms must prioritize seamless integration across the “data–model–decision” chain to address the persistent challenge of multisource data interoperability. Current risk assessment tools in China exhibit three critical deficiencies: low fidelity of multimedia exposure models to real-world environmental scenarios; poor compatibility of health effect assessment tools with omics big data; and inadequate policy relevance of risk characterization models. To resolve these gaps, three specialized toolkits should be developed: (1) intelligent exposure assessment toolkits integrating GIS-based multimedia contaminant migration models, sensor network-driven individual exposure inversion models, and PBPK modules for target tissue dose calculation, enabling cross-scale simulations from macroenvironmental concentrations to microscale biologically effective doses; (2) health effect assessment toolkits deploy machine-learning algorithms that harmonize toxicogenomic data and disease biomarkers to standardize predictive workflows for unified carcinogenic/non-carcinogenic effect frameworks, sensitive subpopulation identification, and chemical mixture synergy evaluation; and (3) risk decision support toolkits featuring Monte Carlo simulation-based uncertainty visualization systems and cloud-based risk assessment operating platforms supplemented with modular resources such as case libraries, parameter databases, and validation protocols.

-

The advancement of China’s EHRATF depends on its capacity to assimilate and transform emerging methodologies. While global risk assessment paradigms have shifted disruptively from traditional approaches to data-driven intelligent systems, China remains in a catch-up phase in critical domains, such as computational toxicology model development, multi-omics integration, and in-vitro microsystem engineering. To overcome bottlenecks, including overreliance on foreign data, weak data interpretation capabilities, fragmented technological chains, and strategic integration of AI, systems biology, and microphysiological systems (MPSs) with environmental health sciences, it is imperative to achieve cutting-edge risk assessment precision and accuracy.

-

There is a need to establish a self-reliant “AI and Environmental Health” technological ecosystem which prioritize the development of three advancements: (1) deep-learning-based multimodal data fusion, deploying graph neural networks to concurrently analyze pollutant molecular structures, physicochemical properties, exposure scenarios, and omics response signals, enabling cross-class toxicity prediction (e.g., carcinogenicity and endocrine disruption) and rapid adaptation of QSAR models to emerging contaminants via transfer learning[86]; (2) causal inference-driven exposure-response modeling, utilizing generative adversarial networks (GANs) to construct virtual population cohorts for simulating multiple-media combined exposures, temporal cumulative effects, and subpopulation susceptibility, transcending the independent-and-identically-distributed (IID) assumptions of traditional regression models[87]; and (3) dynamic risk early-warning systems, integrating satellite remote sensing, Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, and social media data streams with spatiotemporally resolved risk heatmap algorithms for rapid population targeting during pollution emergencies[88]. Concurrently, autonomous computational toxicology software ecosystems must be built, featuring open-source platforms compatible with PBPK/PD models, AOP networks, and quantum chemistry modules, while addressing key challenges such as allometric scaling corrections in cross-species extrapolation and quantitative alignment of organ-on-a-chip data with whole-animal studies.

-

A precise risk assessment paradigm linking the exosome–metabolome–genome–transcriptome–epigenome axes is essential. To resolve mechanistic ambiguity and biomarker specificity gaps, breakthroughs should be prioritized in three key technological areas: (1) exposomic panoramic profiling should advance non-targeted screening methods that can simultaneously detect multiple environmental chemicals and their metabolites[89]; (2) multi-omics integrative frameworks should leverage single-cell transcriptomics to map pollutant-induced cellular heterogeneity[90], combined with epigenome editing technologies such as CRISPR-dCas9 to validate regulatory element impacts, establishing quantitative effect chains from DNA repair to proteostasis disruption[91]; and (3) next-generation MPSs should simulate complex physiological processes (e.g., alveolar–capillary exchange, blood–brain barrier permeation, and hepatorenal metabolic synergy) via 3D organoid chips integrated with microfluidics and biosensors for real-time toxicity monitoring and automated dose–response curve generation[87].

-

Three frontier technologies warrant prioritization: (1) synthetic biology-enabled biosensors, engineering microbial strains for pollutant-specific optical/electrochemical signal generation[92], and developing microfluidic paper-based devices for on-site detection (e.g., multi-ion-activated genetic circuits for water pollution visualization)[93]; (2) quantum computing-enhanced molecular simulations, exploiting qubit parallelism to predict PFAS binding/degradation pathways and optimize QSAR models via nuclear receptor interaction energy modeling[94,95]; and (3) digital twin assessment systems, integrating GIS, climate models, and mobility data to construct spatiotemporal 4D virtual platforms for urban health risk simulation[96]. Additionally, foundational research on organoid standardization, exposomic data dimensionality reduction, and causal machine learning should accelerate the translation of breakthrough technologies into practical risk-assessment applications.

While internationally integrated innovations in new methodologies have advanced significantly, China’s independent development of consolidated models, such as the QSAR–PBPK–AOP model, holds irreplaceable strategic and scientific value. First, the existing global models predominantly rely on physiological parameters and exposure scenarios derived from European and American populations. These studies fail to account for critical metabolic characteristics specific to the Chinese population (e.g., enzyme activity profiles) and regionally distinct exposure patterns (e.g., dietary habits and occupational environments), potentially leading to material biases in risk assessments. Second, as the world’s largest chemical producer, China requires tailored tools aligned with the molecular properties of domestically prevalent chemicals (e.g., agrochemicals/pharmaceuticals) and industrial chain exposure scenarios (e.g., solvent exposure in electronics manufacturing). Critically, autonomous model development serves as the technical foundation for establishing localized regulatory standards, such as emerging contaminant inventories and industry-specific thresholds, while ensuring that sovereignty over core algorithms and databases mitigates “technology containment” risks. Consequently, indigenizing integrated next-generation methodologies is not merely a scientific imperative for enhancing assessment accuracy but also a strategic necessity to safeguard national environmental health security and regulatory autonomy.

-

To develop and refine the technical framework for the EHRA, China should adopt a phased and regionally adaptive approach aligned with its national conditions, characterized by disparities in population density (higher in the east and lower in the west) and uneven economic development across regions. The implementation plan can proceed as follows. First, within 2–3 years, the focus will be on densely populated eastern developed areas and key industrial parks. Priority will be given to formulating foundational methodological standards, such as the Technical Guidelines for Machine Learning-Based Population Health Risk Identification and Specifications for Environmental Exposure Data Collection and Quality Control. Concurrently, coordinated surveys on exposure parameters for vulnerable subpopulations (e.g., pregnant women and the elderly) in both the eastern and central–western regions will be conducted. This will integrate existing data from the Exposure Factors Handbook of the Chinese Population to support subsequent assessments. Second, during years 4 and 5, economically advanced central cities will serve as pilot zones to advance the development of technical guidelines for the EHRA across different media/scenarios. For specific settings such as industrial parks and schools, replicable frameworks will be established by leveraging eastern pilot experiences. Simultaneously, research and development of the Technical Guidelines for the EHRA of Emerging Contaminants (e.g., nanomaterials and microplastics) will be initiated. Finally, over 5 years, mature standards will be extended to central–western and rural areas, with emphasis on emergency-oriented frameworks such as the Risk Assessment Framework for Population Health During Natural Disasters. Parallel efforts will refine uncertainty assessment systems, including the Technical Guidelines for Evidence-Weighted Risk Characterization, to ensure their applicability and operability across regions with varying economic capacities.

We conducted a systematic comparative analysis of domestic and international EHRA technological frameworks and revealed the critical shortcomings of China’s current system, including fragmented technical standards, weak data infrastructure, and insufficient adaptability of modeling tools. To address these challenges, a tripartite “standards–data–innovation” solution is proposed: (1) establishing a full-chain standardized technical framework by adapting international best practices, such as the EU’s REACH tiered risk assessment strategy and the U.S. Tox21 high-throughput screening system, into classification technical guidelines adapted to China’s national conditions; (2) overcoming technical bottlenecks, such as low exposure model fidelity and cross-media toxicity quantification, through intelligent algorithm and multi-source data platform integration; and (3) bridging molecular-to-population assessment gaps via advanced technology convergence, including organ-on-a-chip systems, exposomics, and quantum computing. As the system evolves, it will catalyze a transformative shift toward a full-cycle EHRA paradigm characterized by precision source tracing, intelligent early warning, and dynamic adjustment. This evolution will scientifically empower critical national strategies such as graded environmental health risk management and emerging contaminant governance, ultimately accelerating the synergistic advancement of the Healthy China and Ecological Civilization initiatives through robust, technology-driven risk governance capabilities.

Bottlenecks and Innovative Breakthroughs in the Construction of China’s Environmental Health Risk Assessment Technological System

doi: 10.3967/bes2025.135

- Received Date: 2025-05-24

- Accepted Date: 2025-07-28

The authors have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported herein.

| Citation: | Xiaoyan Yang, Xu Han, Jiaxin Lyu, Qin Wang, Dongqun Xu. Bottlenecks and Innovative Breakthroughs in the Construction of China’s Environmental Health Risk Assessment Technological System[J]. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences, 2025, 38(11): 1329-1350. doi: 10.3967/bes2025.135 |

Quick Links

Quick Links

DownLoad:

DownLoad: