-

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide[1]. In 2018, 2.09 million new breast cancer cases were identified globally, accounting for 11.6% of all cancers in that year[2]. The breast cancer incidence in Asian women has also increased rapidly over the past 30 years. For instance, statistics from China’s National Cancer Center show that the number of women with breast cancer in 2014 and 2015 was 130,000 and 304,000, respectively[3,4], making China the country with the largest burden of breast cancer among women worldwide[5]. Therefore, the influencing factors that lead to the development of breast cancer among women in China, to inform on prevention strategies and reduce the disease onset, must be urgently understood.

Prior studies have indicated that breast cancer is caused by a variety of risk factors with an unclear etiology. In recent years, multiple studies have aimed to address the risk factors associated with the onset of breast cancer, such as demographic factors, reproductive factors, hormonal factors, and other risk factors, which have been analyzed by Zohre Momenimovahed from 142 English-language studies[1]. The results of these studies, however, cannot be generalized to those in China. At present, a few studies in China have explored the risk factors of breast cancer in the occupational, environmental, and psychological aspects and also specifically in Beijing. In this study, we aimed to explore the multidimensional risk factors associated with the development of breast cancer, including demographic characteristics, occupational exposures, and reproductive, environmental, and psychological factors, to establish a risk factor model for breast cancer prevention in Beijing.

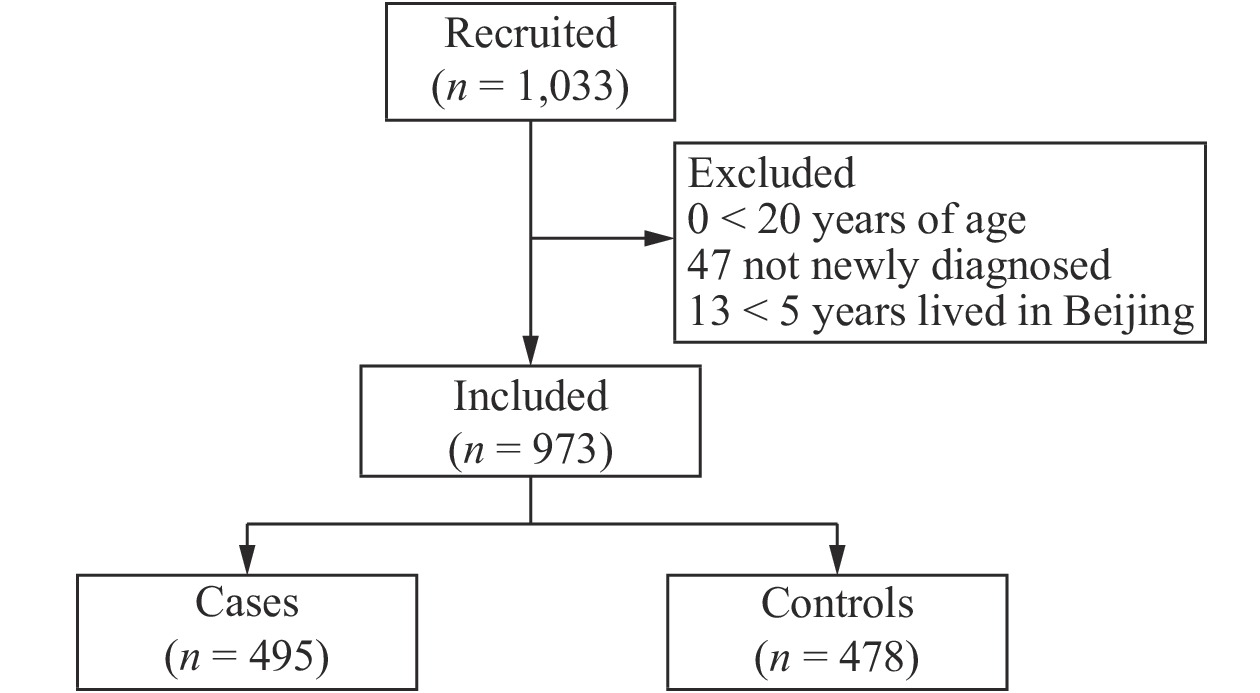

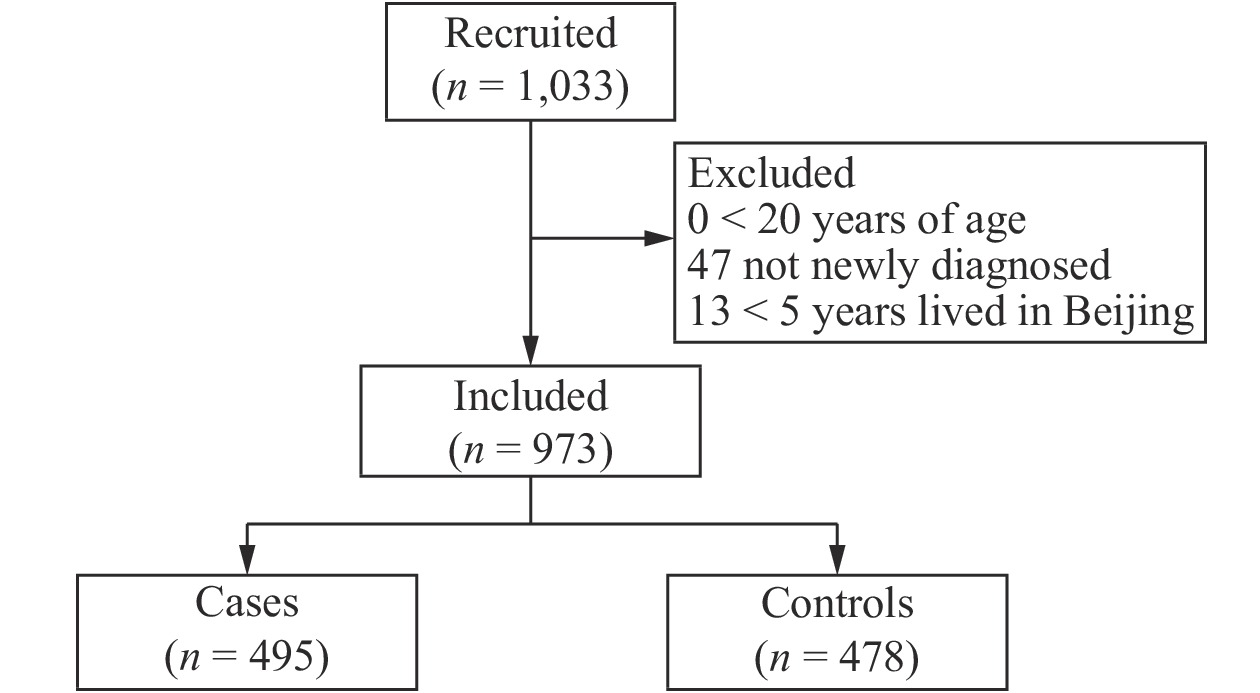

A case-control study was used to explore the risk factors associated with the development of breast cancer in women residing in Beijing city, China, from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019. Patients who were newly diagnosed with breast cancer at one of the eight local hospitals in Beijing were screened for inclusion in the study criteria. The controls were matched from the same hospital where the cases came from. The inclusion criteria of the case group were as follows: (1) female; (2) age between 20 and 84 years; (3) newly diagnosed with primary breast cancer (ICD-10 code 50); and (4) have lived in Beijing for at least 5 years. On the other hand, the inclusion criteria of the controls were as follows: (1) female; (2) age between 20 and 84 years; (3) no medical record of breast cancer but sought medical advice at the same hospital during the same time period; and (4) have lived in Beijing for at least 5 years. All those who met the inclusion criteria and provided an informed consent were included in the study.

Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews using a standardized questionnaire in a private office. Each questionnaire took approximately 15 minutes to complete, the contents of which included basic demographic information [body mass index (BMI), level of education, relationship status, reproductive status, menopausal status, history of benign breast diseases, family history of breast cancer, and age at menarche], occupational and environmental risk factors, and psychological factors. The BMI classification in this paper is based on the guidelines for prevention and control of overweight and obesity in Chinese adults. To determine a family history of breast cancer, each participant was required to report whether his or her immediate relatives (father, mother, or siblings) had ever been diagnosed by a doctor with breast cancer.

In this study, the impact of psychological factors on the development of breast cancer was investigated with a coping-style questionnaire, to reflect the positive and negative attitudes and behavior characteristics in the face of difficult setbacks, which was divided into two dimensions, active responses and negative responses, each containing 10 topics. All participants could choose a response based on a five-grade scoring scale, the active and negative coping-style scores ranging from 10 to 50. The questionnaire has been used throughout China and has good reliability and validity[6].

For the description of participant characteristics, categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages, which are compared using chi-square analysis. Continuous variables are assessed using mean and standard deviation, which are compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test analysis. Multivariate logistic regressions are performed, reporting the P-values, odds ratios (OR), and 95% confidence interval (CI). Odds ratio compares the following: age (< 40), BMI (≤ 18.4), university-level education and above, single marital status, have a history of abortion, postmenopausal, no family history of breast cancer, bedtime before 22:00, have a history of night shift work, history of exposure to industrial dust, history of exposure to high temperatures, minimum value of negative trait coping style, minimum value of active trait coping style, and minimum value of age at menarche. All P-values are two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions software, California, USA. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Beijing Center for Disease Control and Prevention (IRB #201920). The written informed consent for both cases and controls were obtained before the interviews.

A total of 1,033 participants were recruited for the study, and the response rate was 94.86% (1,033/1,089). However, 60 women did not meet the inclusion criteria, so they were subsequently excluded from the study. Thus, a total of 973 participants were left for the final analysis, including 495 breast cancer cases and 478 controls with response rates of 93.73% and 96.05%, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1 available in www.besjournal.com). Table 1 shows the demographic and reproductive characteristics of both cases and controls. Compared to the control group, women with breast cancer were older (P < 0.0001). A total of 57.78% of cases reported a higher BMI (40.81% were 24.0–27.9 kg/m2 and 16.97% ≥ 28.0 kg/m2, P < 0.0001). Less than 30% of cases had a university-level education or above (P < 0.0001), and less than 3% went to sleep between 0:00 and 4:00 (P < 0.0001). More women with breast cancer had previously given birth (93.74%, P < 0.0001), had reached menopause (75.56%, P < 0.0001), and had a family history of breast cancer (8.89%, P = 0.0535). Fewer women with breast cancer reported having an abortion (49.09%, P < 0.0001).

Table 1. Demographic and reproductive characteristics of 973 study participants in Beijing, China

Characteristics Cases (n = 495) Controls (n = 478) P-value No. % No. % Age at interview (years) < 0.0001 Mean ± SD 58.67 ± 11.03 42.86 ± 12.11 < 40 24 4.85 196 41 40–54 137 27.68 201 42.05 55–64 207 41.82 64 13.39 ≥ 65 127 25.66 17 3.56 BMI (kg/m2) < 0.0001 < 18.5 24 4.85 37 7.74 18.5–23.9 185 37.37 290 60.67 24.0–27.9 202 40.81 128 26.78 ≥ 28.0 84 16.97 23 4.81 Education < 0.0001 Middle school and below 179 36.16 48 10.04 High school 181 36.57 82 17.15 University and above 135 27.27 348 72.80 Marital status < 0.0001 Single 10 2.02 66 13.81 Married 435 87.88 387 80.96 Unknown 50 10.10 25 5.23 Bedtime < 0.0001 Before 22:00 189 38.18 104 21.76 Between 22:00 and 24:00 292 58.99 353 73.85 Between 0:00 and 4:00 14 2.83 21 4.39 Previously given birth < 0.0001 Yes 464 93.74 371 77.62 No 31 6.26 107 22.38 Abortion history 0.0122 Yes 243 49.09 273 57.11 No 252 50.91 205 42.89 Menopausal status < 0.0001 Yes 374 75.56 127 26.57 No 121 24.44 351 73.43 History of benign breast diseases 0.2366 Yes 98 19.80 91 19.04 No 360 72.72 364 76.15 Unknown 37 7.47 23 4.81 Family history of breast cancer 0.0535 Yes 44 8.89 24 5.02 No 441 89.09 442 92.47 Unknown 10 2.02 12 2.51 Age at menarche (mean ± SD) 14.03 ± 1.76 13.43 ± 1.48 < 0.0001 Note. No., number; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; Kg, kilogram; m, meters. Compared to the controls, more women diagnosed with breast cancer had exposure to industrial dust, higher temperatures at their workplaces, lower active coping scores, and higher negative response scores (P < 0.05) (Table 2). More controls however had a history of working the nightshift (P = 0.0001) and eating at night (P = 0.0109).

Table 2. Occupational and environmental risk factors for breast cancer among 973 participants from Beijing, China

Characteristics Cases (n = 495) Controls (n = 478) P-value No. % No. % Occupational hazard exposure history Industrial noise Yes 45 9.09 32 6.69 0.1663 No 450 90.91 446 93.31 Industrial dust Yes 45 9.09 18 3.77 0.0007 No 450 90.91 460 96.23 High temperature at the office Yes 28 5.66 9 1.88 0.0021 No 467 94.34 469 98.12 Industrial toxins Yes 41 8.28 27 5.65 0.1071 No 454 91.72 451 94.35 History of nightshift work Yes 122 24.65 172 35.98 0.0001 No 373 75.35 306 64.02 Nighttime eating Yes 48 9.70 72 15.06 0.0109 No 447 90.30 406 84.94 Ventilation in the office Yes 450 90.91 431 90.17 0.6926 No 45 9.09 47 9.83 Coping style scores Active (mean ± SD) 33.72 ± 8.77 35.14 ± 7.94 0.0326 Negative (mean ± SD) 28.00 ± 8.34 25.90 ± 7.31 < 0.0001 The statistically significant variables in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis. After controlling for confounding, the factors significantly associated with higher odds of breast cancer were older age (P < 0.0001, for those aged 55 and above), less education (P < 0.0001), having a family history of breast cancer (P = 0.0278), and having a negative coping style (P = 0.0014) (Table 3).

Table 3. Analysis of risk factors of breast cancer using multivariate logistic regression

Characteristics P-value OR (95% CI) Age (years) < 40 1.00 40–54 0.0003 2.91 (1.62, 5.20) 55–64 < 0.0001 8.52 (4.09, 17.76) ≥ 65 < 0.0001 21.67 (8.82, 53.2) BMI (kg/m2) ≤ 18.4 1.00 18.5–23.9 0.2185 0.63 (0.31, 1.31) 24.0–27.9 0.8352 1.08 (0.52, 2.27) ≥ 28.0 0.1432 1.94 (0.8, 4.72) Education Middle school and below < 0.0001 3.78 (2.36, 6.08) High school < 0.0001 2.44 (1.61, 3.68) University and above 1.00 Marital status Single Married 0.4483 1.51 (0.52, 4.42) Unknown 0.3225 1.82 (0.56, 5.97) Previously given birth Yes 1.00 No 0.8469 1.07 (0.54, 2.11) Abortion history Yes 1.00 No 0.5707 1.11 (0.78, 1.57) Menopausal status Yes 0.0609 1.57 (0.98, 2.51) No 1.00 Family history of breast cancer Yes 0.0278 2.05 (1.08, 3.90) No 1.00 Unknown 0.0064 0.20 (0.07, 0.64) Bedtime Before 22:00 1.00 Between 22:00 and 24:00 0.1968 1.29 (0.88, 1.92) 0:00–4:00 0.6935 1.22 (0.45, 3.31) History of nightshift work Yes 0.1592 1.31 (0.90, 1.90) No 1.00 History of exposure to occupational hazards Industrial dust Yes 0.1355 1.73 (0.84, 3.54) No 1.00 Exposure to high temperatures at the office 0.2882 1.68 (0.65, 4.37) Yes No 1.00 Trait coping style Negative 0.0014 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) Active 0.1504 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) Age at menarche 0.2387 1.07 (0.96, 1.19) Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; Kg, kilogram; m, meters. Our results suggested that older age was a risk factor in developing breast cancer. Consistent with our study, research studies have found that elderly women are less likely to be screened for breast cancer, and screening could reduce related mortality by 15%–20%[7]. As a growing portion of the population in China ages, this could place an increased burden on the health and economic sectors due to the increasing need to support the long-term care and treatment of those women who develop breast cancer. Initiatives, which aim to promote screening education within this unique group, should be developed, while more targeted screening policy measures for the elderly should be advocated for at the national level.

In this study, those with higher levels of education had decreased risks of developing breast cancer, which is consistent with previous studies, stating that those with higher levels of education are more likely to participate in breast cancer screenings at their own initiative[8]. Thus, increased screening awareness should be promoted among less-educated populations to increase early detection and achieve better prevention, treatment, and prognosis among women in Beijing.

Family history of breast cancer was also significantly associated with higher risks of developing breast cancer. Shared genetic components and environmental influencing factors can impact family risk exposure for breast cancer, such as reproductive risk factors. Therefore, advocating for improved screening campaigns and techniques specifically targeted on women with a family history of breast cancer is needed, policies that are not currently in place in China.

This study also found that a negative coping style also slightly increased the risks of breast cancer among participants. Other studies have found that those with less ability to cope with demanding situations may be more prone to stress, which could be associated with the development of breast cancer[9]. Additionally, a negative psychological impact could also be an adverse effect for breast cancer screening. Therefore, health professionals should advocate for additional mental health resources for women with a high risk for developing breast cancer and include these services for the overall care and treatment of women with breast cancer in Beijing.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a case-controlled study, which may have resulted in recall bias and self-report bias. In the study, investigators were trained to adapt their questioning techniques and discuss the past 5 years only to reduce the occurrence of recall bias. Second, we recruited controls from hospitals rather than from the general population; thus, selection bias from controls may exist. To reduce the potential bias caused by using hospital-based controls, we excluded those with breast-related diseases and instead recruited those who were presenting to the hospital for a variety of reasons. This way, we hoped to capture patients who would be representative of the general patient population, not just those that may be sickest. Lastly, this study did not include information on some well-established risk factors of breast cancer, such as age at menopause or hormone use; we could further do a follow-up among these case-control study participants to determine such factors.

Our findings highlight particular risk factors that may lead to increased risks of developing breast cancer among women in Beijing, such as older age, less education, and a family history of breast cancer. National awareness campaigns that aim to promote screening, particularly among older, less-educated individuals, coupled with improved policies to screen and prioritize patients with a history of breast cancer, should be implemented to reduce the burden of breast cancer throughout China.

doi: 10.3967/bes2020.105

Multidimensional Analysis of Risk Factors Associated with Breast Cancer in Beijing, China: A Case-Control Study

-

-

Table 1. Demographic and reproductive characteristics of 973 study participants in Beijing, China

Characteristics Cases (n = 495) Controls (n = 478) P-value No. % No. % Age at interview (years) < 0.0001 Mean ± SD 58.67 ± 11.03 42.86 ± 12.11 < 40 24 4.85 196 41 40–54 137 27.68 201 42.05 55–64 207 41.82 64 13.39 ≥ 65 127 25.66 17 3.56 BMI (kg/m2) < 0.0001 < 18.5 24 4.85 37 7.74 18.5–23.9 185 37.37 290 60.67 24.0–27.9 202 40.81 128 26.78 ≥ 28.0 84 16.97 23 4.81 Education < 0.0001 Middle school and below 179 36.16 48 10.04 High school 181 36.57 82 17.15 University and above 135 27.27 348 72.80 Marital status < 0.0001 Single 10 2.02 66 13.81 Married 435 87.88 387 80.96 Unknown 50 10.10 25 5.23 Bedtime < 0.0001 Before 22:00 189 38.18 104 21.76 Between 22:00 and 24:00 292 58.99 353 73.85 Between 0:00 and 4:00 14 2.83 21 4.39 Previously given birth < 0.0001 Yes 464 93.74 371 77.62 No 31 6.26 107 22.38 Abortion history 0.0122 Yes 243 49.09 273 57.11 No 252 50.91 205 42.89 Menopausal status < 0.0001 Yes 374 75.56 127 26.57 No 121 24.44 351 73.43 History of benign breast diseases 0.2366 Yes 98 19.80 91 19.04 No 360 72.72 364 76.15 Unknown 37 7.47 23 4.81 Family history of breast cancer 0.0535 Yes 44 8.89 24 5.02 No 441 89.09 442 92.47 Unknown 10 2.02 12 2.51 Age at menarche (mean ± SD) 14.03 ± 1.76 13.43 ± 1.48 < 0.0001 Note. No., number; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; Kg, kilogram; m, meters. Table 2. Occupational and environmental risk factors for breast cancer among 973 participants from Beijing, China

Characteristics Cases (n = 495) Controls (n = 478) P-value No. % No. % Occupational hazard exposure history Industrial noise Yes 45 9.09 32 6.69 0.1663 No 450 90.91 446 93.31 Industrial dust Yes 45 9.09 18 3.77 0.0007 No 450 90.91 460 96.23 High temperature at the office Yes 28 5.66 9 1.88 0.0021 No 467 94.34 469 98.12 Industrial toxins Yes 41 8.28 27 5.65 0.1071 No 454 91.72 451 94.35 History of nightshift work Yes 122 24.65 172 35.98 0.0001 No 373 75.35 306 64.02 Nighttime eating Yes 48 9.70 72 15.06 0.0109 No 447 90.30 406 84.94 Ventilation in the office Yes 450 90.91 431 90.17 0.6926 No 45 9.09 47 9.83 Coping style scores Active (mean ± SD) 33.72 ± 8.77 35.14 ± 7.94 0.0326 Negative (mean ± SD) 28.00 ± 8.34 25.90 ± 7.31 < 0.0001 Table 3. Analysis of risk factors of breast cancer using multivariate logistic regression

Characteristics P-value OR (95% CI) Age (years) < 40 1.00 40–54 0.0003 2.91 (1.62, 5.20) 55–64 < 0.0001 8.52 (4.09, 17.76) ≥ 65 < 0.0001 21.67 (8.82, 53.2) BMI (kg/m2) ≤ 18.4 1.00 18.5–23.9 0.2185 0.63 (0.31, 1.31) 24.0–27.9 0.8352 1.08 (0.52, 2.27) ≥ 28.0 0.1432 1.94 (0.8, 4.72) Education Middle school and below < 0.0001 3.78 (2.36, 6.08) High school < 0.0001 2.44 (1.61, 3.68) University and above 1.00 Marital status Single Married 0.4483 1.51 (0.52, 4.42) Unknown 0.3225 1.82 (0.56, 5.97) Previously given birth Yes 1.00 No 0.8469 1.07 (0.54, 2.11) Abortion history Yes 1.00 No 0.5707 1.11 (0.78, 1.57) Menopausal status Yes 0.0609 1.57 (0.98, 2.51) No 1.00 Family history of breast cancer Yes 0.0278 2.05 (1.08, 3.90) No 1.00 Unknown 0.0064 0.20 (0.07, 0.64) Bedtime Before 22:00 1.00 Between 22:00 and 24:00 0.1968 1.29 (0.88, 1.92) 0:00–4:00 0.6935 1.22 (0.45, 3.31) History of nightshift work Yes 0.1592 1.31 (0.90, 1.90) No 1.00 History of exposure to occupational hazards Industrial dust Yes 0.1355 1.73 (0.84, 3.54) No 1.00 Exposure to high temperatures at the office 0.2882 1.68 (0.65, 4.37) Yes No 1.00 Trait coping style Negative 0.0014 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) Active 0.1504 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) Age at menarche 0.2387 1.07 (0.96, 1.19) Note. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; Kg, kilogram; m, meters. -

[1] Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H. Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer, 2019; 11, 151−64. [2] Freddie B, Jacques F, Isabelle S, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018; 68, 394−424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [3] Sun K, Zheng R, Zhang S, et al. Report of Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Different Areas of China, 2015. China Cancer, 2019; 28, 1−11. (In Chinese) [4] Chen W, Sun K, Zheng R, et al. Report of Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Different Areas of China, 2015. China Cancer, 2018; 27, 1−14. (In Chinese) [5] Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, et al. The global burden of cancer 2013. JAMA Oncology, 2015; 1, 505−27. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0735 [6] Zhang JJ, Jia JM, Tao N, et al. Mediator effect analysis of the trait coping style on job stress and fatigue of the military personnel stationed in plateau and high cold region. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi, 2017; 35, 176−80. (In Chinese) [7] Marmot MG, Altman DG, Cameron DA, et al. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Br J Cancer, 2013; 108, 2205−40. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.177 [8] Willems B, Bracke P. Participants, Physicians or Programmes: Participants’ educational level and initiative in cancer screening. Health Policy, 2018; 122, 422−30. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.02.001 [9] Tomita M, Takahashi M, Tagaya N, et al. Structural equation modeling of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and psychosocial factors in women with breast cancer. Psycho-oncology, 2017; 26, 1198−204. doi: 10.1002/pon.4298 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links