-

The frequency of pathogenic copy number variations (CNVs) in spontaneous pregnancy losses is comparable to prenatal diagnosis sampling results[1, 2]. In a pilot study we showed that the frequency of copy number loss on chromosome 8p23.3 was the highest among 3,477 abortion samples tested by a SNP array (unpublished data). Indeed, the dosage effect of genes located in the chromosome 8p23.3 region are important for prenatal diagnosis and consultation[3]. There are seven OMIM genes in the chromosome 8p23.3 region, including FBXO25[4, 5], TDRP[5], DLGAP2, CLN8, ARHGEF10, KBTBD11, and MYOM2. Among the OMIM genes, only the dosage effect of the CLN8 gene has been clearly established (neither haploinsufficiency nor autosomal recessive)[6-10]. A missing double allele or loss-of-function CLN8 mutation can cause progressive epilepsy and developmental degeneration in children 5–10 years of age, and can also lead to neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, which has an earlier onset of symptoms, such as ataxia, speech delay, vision loss, and seizures[11-13]. Genes that have similar functions are clustered in multi-megabase regions of individual chromosomes [14]. The mutations of genes in multi-megabase regions of individual chromosomes, including FBXO25[4, 5], TDRP[5] and DLGAP2[15], can lead to neurologic symptoms. ARHGEF10 (MIM#608136) is the only gene that causes autosomal dominant disease with a nervous system phenotype[16], but it is unclear if ARHGEF10 is haploinsufficient. Moreover, neurologic abnormalities are difficult to detect during pregnancy and the ambiguity of the haploinsufficient effect is an enormous challenge during prenatal consultation. Therefore, we sought to determine the dosage effect of ARHGEF10 in the current study to provide clinically meaningful evidence for use during prenatal consultation.

ARHGEF10 is located on human chromosome 8p23.3, has 29 exons, encodes 1368 amino acids and contains a Dbl homology (DH) domain (codons 397–581; exons 12–16), which is a common feature of all Rho family of GTPase proteins[17]. ARHGEF10 encodes a guanine-nucleotide exchange factor for the Rho family of GTPase proteins and activates Rho GTPases by catalyzing the exchange of a G-protein-bound GDP for GTP as a rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF). Rho GTPases are involved in neurodevelopmental processes, including neurogenesis, differentiation, gene expression, membrane transportation, vesicle transportation, and the establishment of synaptic plasticity[18-21]. Rho GTPase disorders can lead to of neurodevelopmental diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, inflammation, and neuropathic pain[19, 22, 23]. A heterozygous mutation of ARHGEF10 (g.63687C>T [p.Thr332Ile]) is associated with thinning of peripheral nerve myelin and reduced nerve conduction speed[16, 24, 25], while ARHGEF10 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) lead to increased susceptibility to chemotherapy-induced peripheral nerve diseases[26] and an increased risk of schizophrenia[27]. Knocking out Arhgef10 in mice causes autism-like phenotypes, such as social interaction disorders, hyperactivity, depression, and anxiety behaviors[28], suggesting that ARHGEF10 might be dosage-sensitive and related to phenotypic severity; however, additional direct evidence is needed. Zebrafish have emerged as powerful biological models for nervous system-related research[29]. Therefore, in this study we used zebrafish to determine if arhgef10 has a haploinsufficient effect.

-

Wild-type embryos were derived from natural matings of Tübingen zebrafish. Embryos were raised at 28.5 °C in Holtfreter’s solution. The arhgef10−/− and arhgef10+/− mutants were identified by genotyping, as described below.

-

A MEGAscript kit (Ambion, Austin, Texas, USA) was used to synthesize digoxigenin-UTP-labeled RNA probes in vitro from linearized plasmids, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Embryos were fixed overnight at 4 °C using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for hybridization. After using PBS to wash PFA 4 times (5 min each), the embryos were twice-washed with 100% methanol (5 min each). WISH was performed, as previously described[30]. -

Cas9 mRNA was transcribed from pGH-T7-zCas9 in vitro using a protocol optimized for zebrafish, as previously described[31]. Cas9 mRNA (200 pg) was injected in zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage. Then, arhgef10 (GenBank accession number NC_007128.7; Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) guide-RNA (gRNA) was synthesized, as previously described[31]. We designed 4 zebrafish arhgef10-specific gRNAs for gene-specific editing of arhgef10 exons 12 and 13 (Table 1).

Table 1. gRNA for gene-specific editing of arhgef10 exons 12 and 13

gRNA Sequences (5’– 3′) ahgef10-exon12-1 GAAACACCACCTTACGCTTG ahgef10-exon12-2 ATCCCAGTCAGATACTCTGC ahgef10-exon13-1 AGCGTCCAACACCATAGACT ahgef10-exon13-2 GTCCAGGAAACAGGGTTTAG To synthesize the gRNA template, oligos were amplified by PCR reactions. A MAXIscript T7 kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) was used to transcribe gRNA in vitro. TURBO DNase (Life Technologies) was used to remove the DNA template. Phenol chloroform was used to purify the product after synthesis. gRNA and Cas9 mRNA were injected into zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage.

-

To extract genomic DNA from zebrafish embryos or tail fin clips, samples were lysed in 50 mmol/L NaOH, then boiled at 95 °C for 30 min. To neutralize the lysates, a 10% volume of 1 mol/L Tris (pH = 8.0) was added to the solution after boiling. After neutralization, the lysates were used as templates in PCRs. The successful targeting of arhgef10 was validated by a PCR reaction. The primers for the region flanking the target site was as follows: arhgef10 fwd, 5′-GATGATTGGGATGCATGAGAGTT-3′; and arhgef10 rev, 5′-CGGGTCTACATGTAATTACTGCA-3′. The amplified fragments were identified by Sanger DNA sequencing for genotyping.

After identifying successful germline-transmitted mutant loci, the surviving embryos were raised to adulthood and screened for germ-line mutated founders. Next, the mutational founders were outcrossed with wild-type zebrafish to generate F1s. Zebrafish were genotyped by PCRs using the following primers: arhgef10 fwd, 5′-TGGCTCAGGTCTGTTTGTGA-3′; and arhgef10 rev, 5′-ACTGCTGTCATGCACAAAGG-3′. The PCR products were then run on a 10% TBE-PAGE gel to distinguish homozygous from heterozygous carriers. The amplified fragment of the wild-type was 261 bp and the amplified fragment of mutant was 140 bp. Finally, F1 was mated to screen for homozygous F2.

-

The heads of zebrafish 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) were ground into powder in grinding bowls with liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies), followed by clean-up using an RNeasy Mini-kit (Qiagen, Germantown, WI, USA). RNA abundance was measured after isolation using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at an absorbance of 260 nm by calculating the A260/A230 and A260/A280 ratios. All isolated nucleic acids were stored at −80 °C. mRNA reverse transcription was generated using an Invitrogen SuperScript kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using a LightCycler 96 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with SYBR Premix (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan). Zebrafish were genotyped by qRT-PCR reactions using the following primers for the arhgef10 gene: fwd, 5'-TGGCTCAGGTCTGTTTGTGA-3'; and rev, 5'-ACTGCTGTCATGCACAAAGG-3'. The PCRs were performed under the following conditions: initiation at 95 ˚C for 30 s; an d40 cycles of amplification at 95 ˚C for 5 s and at 60 ˚C for 30 s. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. Data were normalized to beta-action using the ΔΔCt method.

-

The swimming behavior 120 h post-fertilization (hpf) larvae was assessed in 48-well plates. Twenty larvae in wild-type, arhgef10+/−, and arhgef10−/− groups were placed individually in each well with 2 mL of Holtfreter’s solution. All larvae were prepared 30 min before the beginning of observation. Zebrafish larvae were placed in a DanioVision Observation Chamber (EthoVision®, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands), and videos were recorded for 60 min to measure the distance traveled by the larvae. All of the swimming behavior recordings took place between 11:00 am and 12:30 pm.

-

Zebrafish larvae were placed in 48-well plates, as described above. All larvae were prepared 30 min before the beginning of observation. Each larva was recorded for a total of 30 min with 2.5 light/dark cycles (each consisting of 5 min of light and 5 min of dark). The light intensity for photomotor responses was 100 lx and the frame rate was 25/s.

-

Human SH-SY5Y cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) enhanced with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in a humidified incubator at 37 °C containing 5% CO2. Cell transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

-

SH-SY5Y cell total protein was extracted using 2 × SDS lysis buffer at 4 °C, and quantified using the Bradford assay. Equivalent measures of protein were isolated on SDS-PAGE gels. The gels were transferred onto PVDF membranes (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (11021037; Thermo Fisher) and probed with primary antibodies, including anti-ARHGEF10 (Proteintech, Hubei, China) and anti-GAPDH (Proteintech) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed with TBS and 0.1% Tween 20, then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, stained with chemiluminescence (Millipore, MA, USA) reagent and visualized. GAPDH served as a loading control. Protein levels were quantified using NIH ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA)(version 1.8.0).

-

Cell viability was determined with a Cell Counting Kit-8 (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) at 24, 48, and 72 h. Then, after adding 10 μL of CCK-8 solution to each well, the cells were cultured in an incubator for 1 h in the dark. A Multiskan SkyHigh Microplate reader (Thermo Fisher) was used to measure the absorbance of each sample at 450 nm. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. -

SH-SY5Y cells were collected and seeded into 6-cm dishes. Cells were digested with 0.25% trypsin after 48 h of growth and collected with PBS on ice. Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) was added to cells for 10 min at 25 °C, then propidium iodide (PI) was added for 3 min at 25 °C in the dark. Fluorescence intensity was analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and data were processed with FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

-

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to compare the locomotor experimental data of three genotypes. All the experiments were performed three times. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM.

-

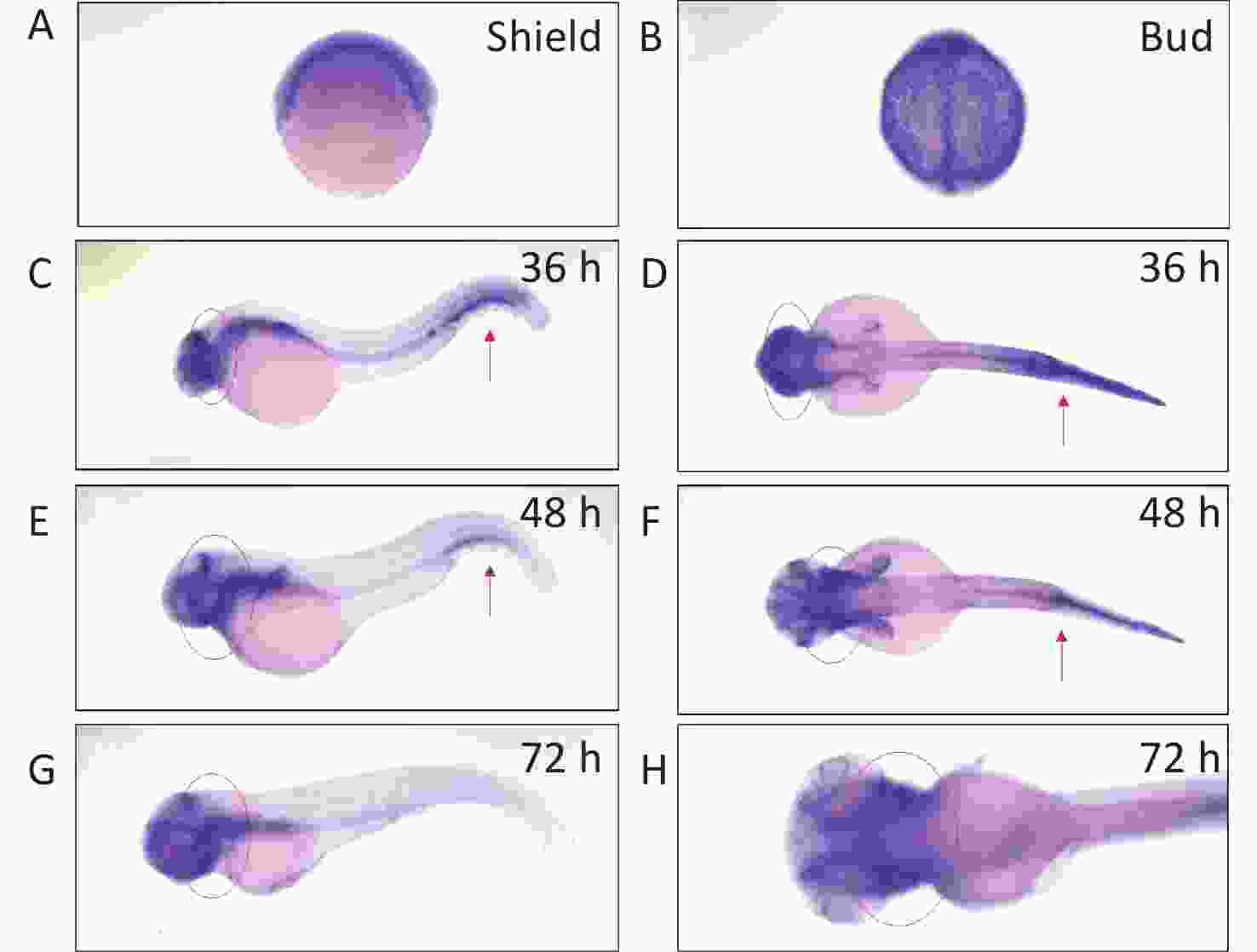

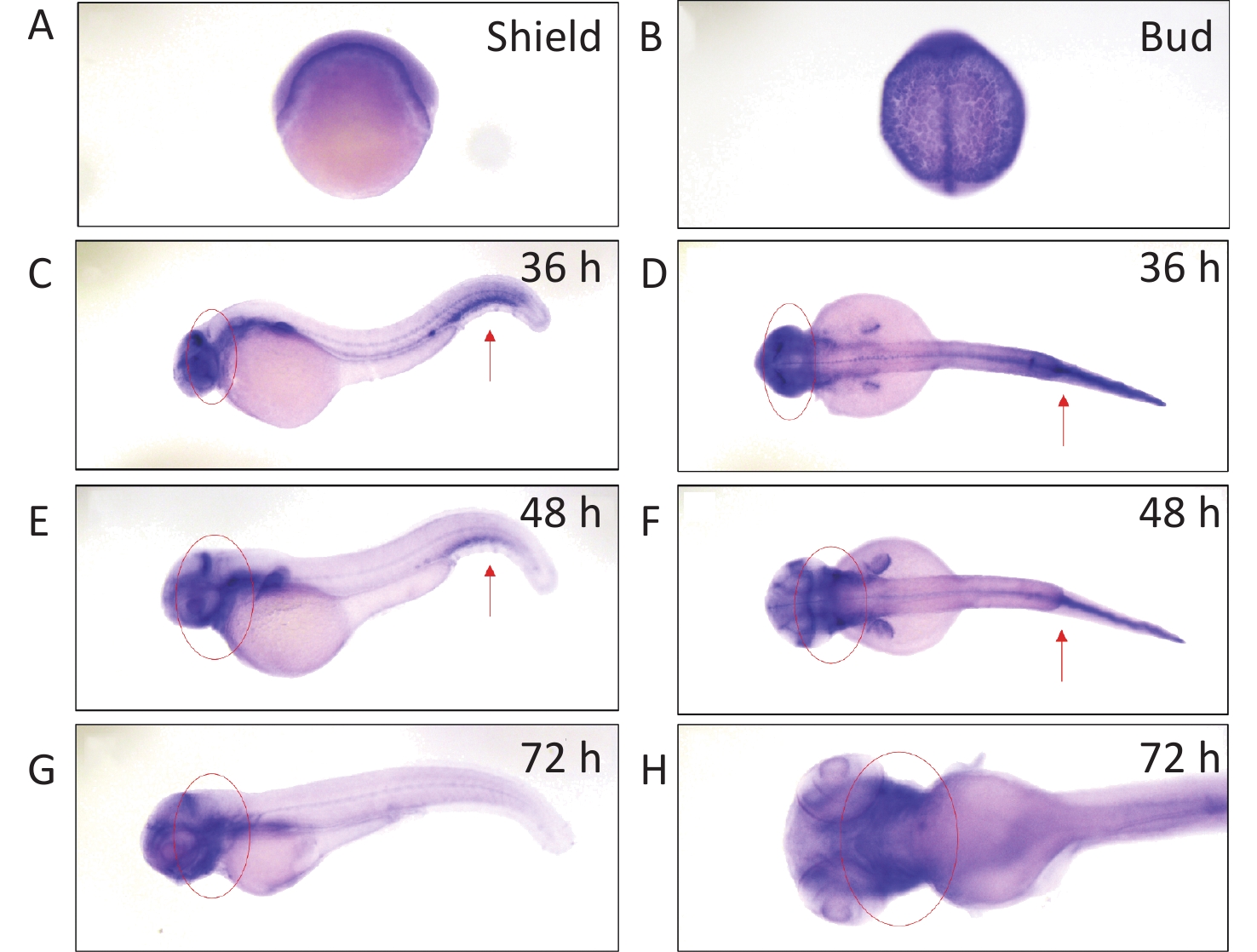

We determined arhgef10 expression using zebrafish larvae from shield to 72 hpf. We identified arhgef10 protein in the zebrafish sharing 66% identity with human ARHGEF10. We conducted RNA whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) experiments in zebrafish from bud to 72 hpf. Before 36 hpf during zebrafish early embryonic development, arhgef10 was ubiquitously expressed (Figure 1A–B). At 36 hpf and 48 hpf, high levels of ahrgef10 expression were detected in the midbrain and hindbrain, with a pronounced expression in hemopoietic system (Figure 1C–F). At 72 hpf, arhgef1 was only expressed in the midbrain and hindbrain (Figure 1G–H).

Figure 1. Detection of arhgef10 expression during early embryogenesis in wild-type zebrafish. (A–H) Wild-type embryos after whole-mount in situ hybridization using an antisense probe for arhgef10 at the indicated developmental stages. The red arrow points to high expression of arhgef10 in the hemopoietic system. The red circle indicates high expression of arhgef10 in the midbrain and hindbrain of zebrafish larvae.

-

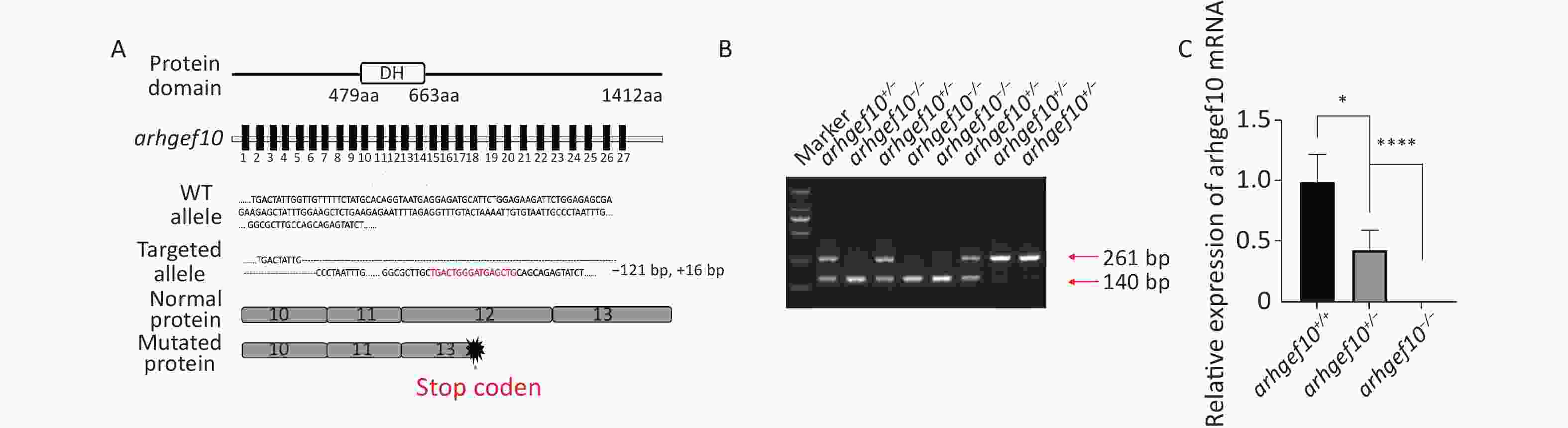

CRISPR/Cas9 technology was used to construct a zebrafish model with a single copy or homozygous arhgef10 deletion. DNA sequencing for target-specific PCR products confirmed that the successful arhgef10-targeted allele carried a deletion of 121 bases and an insertion of 16 bases, resulting in a frameshift mutation truncated from exon 13. The mutation disrupted all known functional domains of the arhgef10 protein (Figure 2A, B). Homozygous deletion of arhgef10 (arhgef10−/−) was obtained from the heterozygote (arhgef10+/−) cross after mating heterozygote mutants with the wild-type for three generations. The arhgef10 mRNA expression in brains of arhgef10+/+, arhgef10+/,- and arhgef10−/− larvae were examined 5 dpf by real-time PCR. The relative expression of arhgef10 mRNA in the brains of arhgef10+/− larvae was significantly decreased (0.35-fold) compared to arhgef10+/+ larvae, and there was no expression of arhgef10 mRNA in the brains of arhgef10−/− larvae 5 dpf (Figure 2C). These results indicated that we successfully generated arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− zebrafish.

Figure 2. Generation of the arhgef10 deletion model in zebrafish by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. (A) Sketch map of the zebrafish arhgef10 gene and protein. The CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutation (121-base deletion and 16-base insertion) in arhgef10 is shown in the annotated arhgef10 mutant sequences. The nucleotides in red are inserted sequences and “-” are deleted nucleotides. (B) Identification of the copy number losses model by PCR. The PCR product for wild-type was 261 bp and for the ahrgef10 deletion was 140 bp. (C) The relative expression of arhgef10 mRNA in the brains of arhgef10+/+, arhgef10+/−

, and arhgef10−/− larvae 5 dpf (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, respectively). -

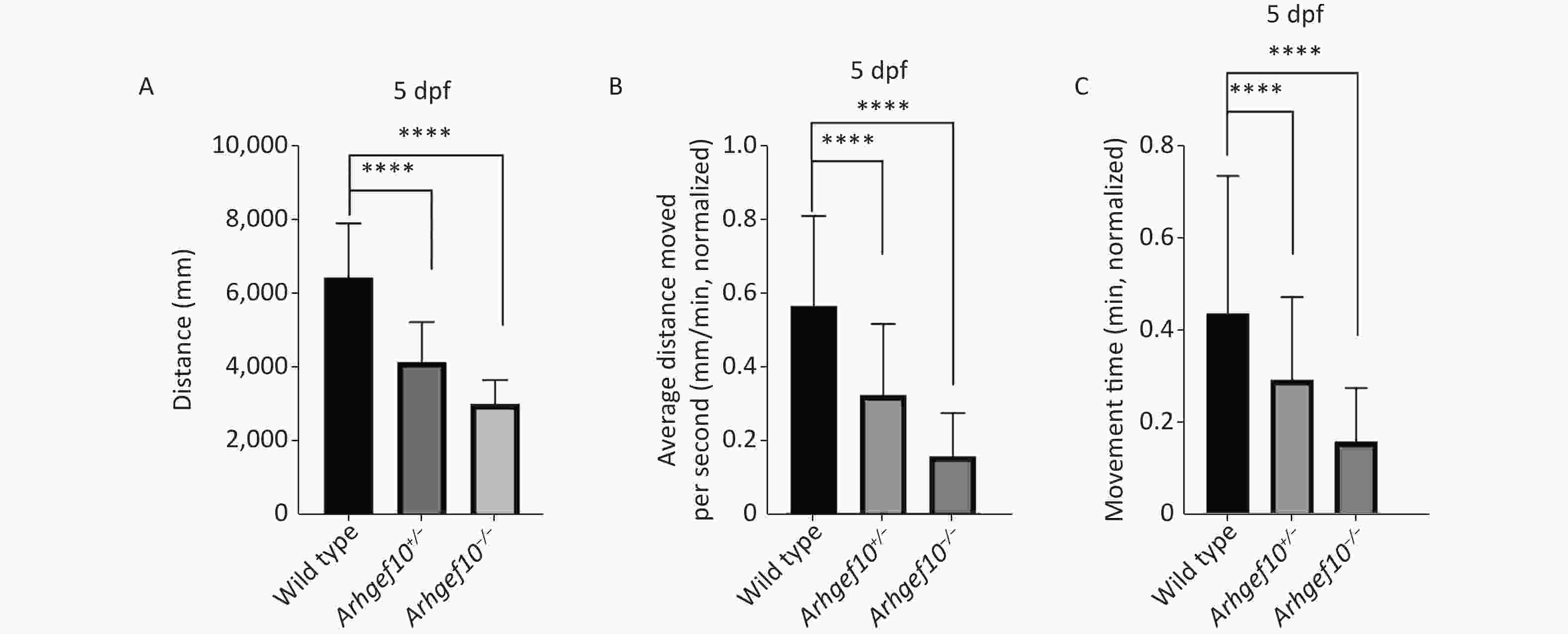

To determine whether the single copy loss of arhgef10 affected larval behaviors during development, the moving distance, average distance moved per min, and movement time were measured among wild-type, arhgef10+/−, and arhgef10−/− zebrafish. The Danio System was used to measure its trajectory by putting each zebrafish larva into a hole of a 48-well plate, and the data were saved. After the behavioral experiment, larvae 5 dpf were lysed and DNA from each group was extracted. The genotypes were determined. The moving distance of wild-type, arhgef10+/−, and arhgef10−/− larvae was 6,476 ± 331.4 mm, 4,187 ± 242.2 mm, and 3,046 ± 146.0 mm, respectively. The normalized average distance moved per min of wild-type, arhgef10+/−, and arhgef10−/− larvae was 0.57 ± 0.06 mm/min, 0.33 ± 0.04 mm/min, and 0.16 ± 0.03 mm/min, respectively. The spontaneous activity of arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− larvae was significantly reduced compared with wild-type larvae (P < 0.0001). The normalized movement time of wild-type, arhgef10+/−, and arhgef10−/− larvae was 0.44 ± 0.07 min, 0.29 ± 0.04 min, and 0.15 ± 0.02 min, respectively. The moving distance, average distance moved per minute, and movement time of arhgef10−/− and arhgef10+/− larvae was significantly less than arhgef10+/+ larvae 5 dpf; arhgef10−/− larvae performed significantly worse than arhgef10+/− larvae (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Spontaneous activity of wild type, arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− larvae 5 dpf. (A) Distance traveled in 60 min 5 dpf. (B) Average distance moved per minute 5 dpf. (C) Movement time during 60 min 5 dpf. The vertical axis shows the normalized distance (mm) traveled by larvae in each 1-min bin. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; n = 20 for each genotype).

-

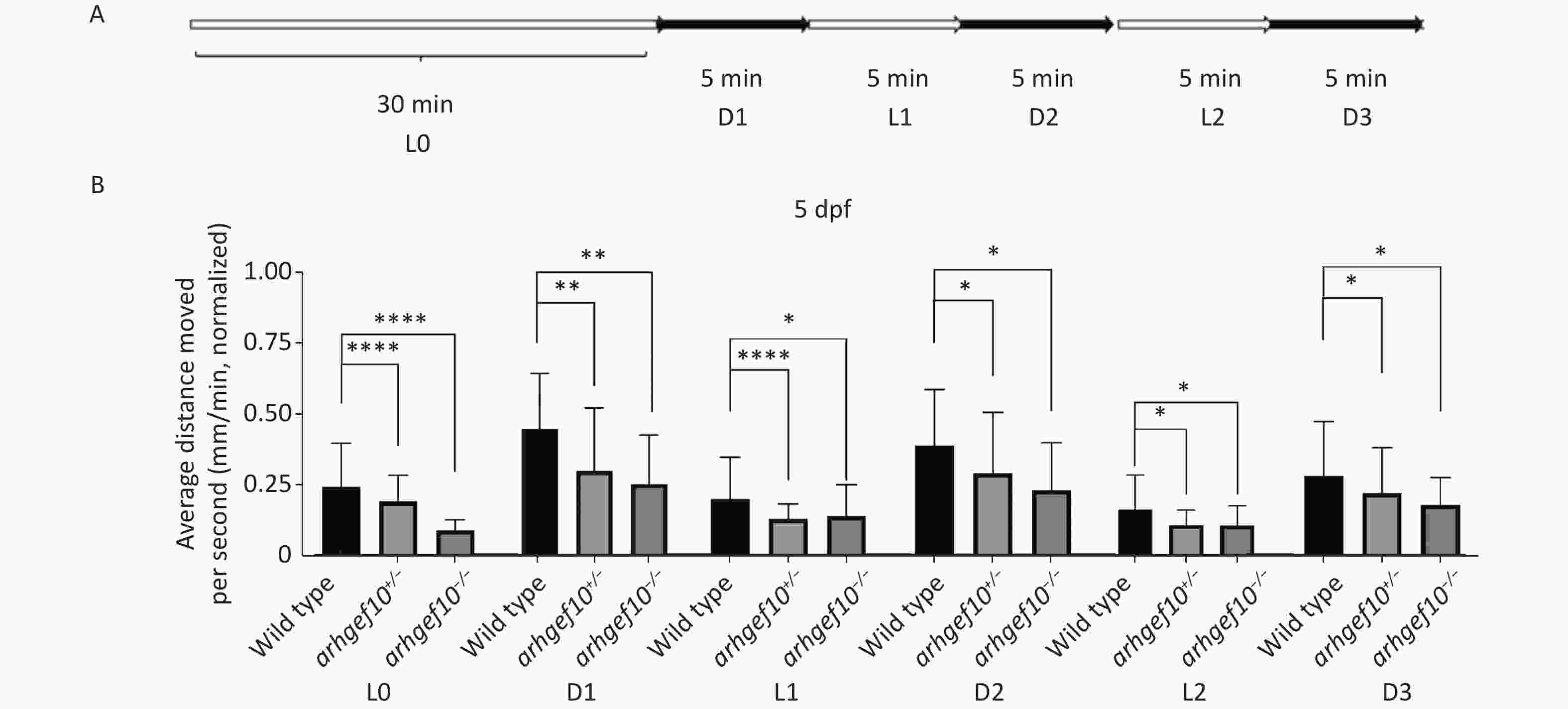

We also examined the responses of zebrafish larvae evoked by light (L)-to-dark (D) and D-to-L changes. Each larva had relatively stable activity following 25-min 2.5 L-to-D cycles after a 30-min habituation period (Figure 4A). Under illumination, the total distance traveled by arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− larvae was significantly less than wild-type larvae, and arhgef10−/− larvae performed significantly worse than arhgef10+/− larvae. L-to-D transitions caused sudden increases in the total distance traveled, while D-to-L transitions resulted in a sudden decreased distance traveled in all zebrafishes; however, arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− larvae showed fewer responses to switches in illumination (Figure 4B). Thus, the copy number losses of arhgef10 may damage the responses of zebrafish larvae evoked by environmental changes.

Figure 4. Light-to-dark test of wild-type, arhgef10+/−, and arhgef10−/− larvae 5 dpf. (A) The program of the test. The activity was recorded during 30 min of light (L0) and 2.5 cycle of 5 min light-to-dark intervals [5 min dark (D1) – 5 min light (L1) – 5 min dark (Ds2) – 5 min light (L2) – 5 min dark (D3)]. (B) The average distance moved per min in each light or dark period 5 dpf. The vertical axis shows the normalized distance (mm) traveled by larvae in each 1-min bin. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; n = 20 for each genotype).

-

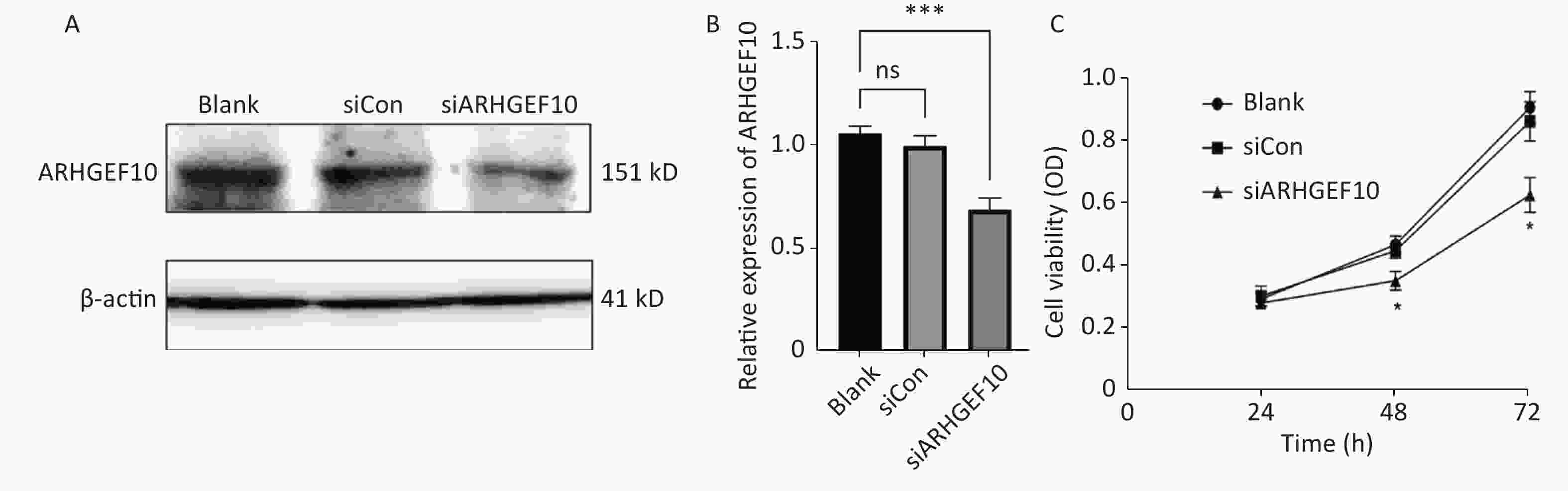

To determine the mechanism underlying the phenotype of ARHGEF10 losses, we knocked down ARHGEF10 in the SH-SY5Y cell line by introducing small interferon RNA (siRNA). After knockdown of arhgef10 in SH-SY5Y cells, the expression of arhgef10 was significantly reduced in siARHGEF10 cells compared to untreated cells (Blank) cells or cells treated with control siRNA (siCon). ARHGEF10 was knocked down in SH-SY5Y cells and the efficacy was verified by western blot analysis (Figure 5A, B).

Figure 5. Expression analysis of proteins in SH-SY5Y cells and cell proliferation in the ARHGEF10 knockdown SH-SY5Y cell line. (A) Western blot analysis of ARHGEF10 protein expression in Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 cells. (B) Quantitative analysis of ARHGEF10 protein in Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 cells. (C) The cell viability was measured at 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection by the CCK-8 assay. Cells were untreated (Blank), treated with control siRNA (siCon), or anti-ARHGEF10 siRNA (siARHGEF10). The visualized protein signals were transferred to quantitative expression by ImageJ software. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). ns, no statistical differences; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

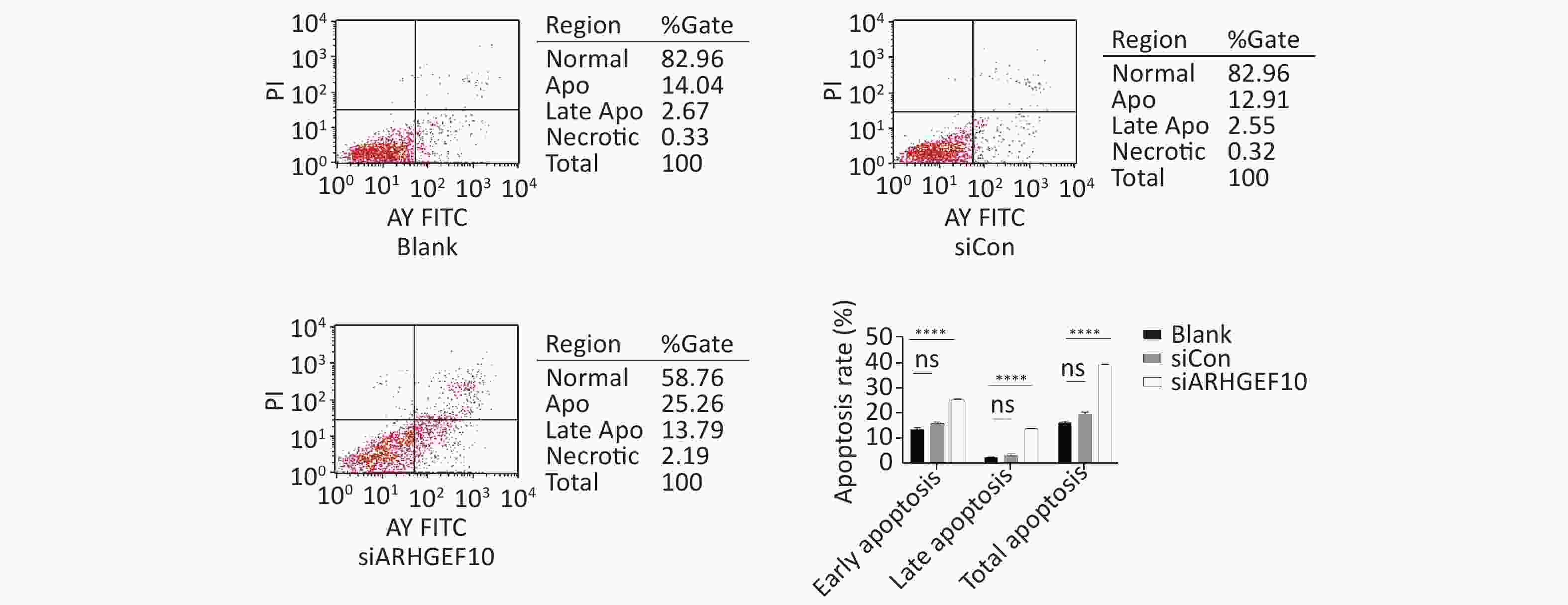

Then, we examined the effect of ARHGEF10 on cell proliferation and apoptosis. CCK-8 assays were used to determine cell viability. Cell proliferation ability was decreased after knocking down ARHGEF10 compared with the blank and siCon cells (Figure 5B). Flow cytometry analysis showed that early apoptotic cells accounted for 14.04%, 12.91%, and 25.26% in the Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 groups, respectively. Late apoptotic cells accounted for 2.67%, 2.55%, and 13.79% in the Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 groups, respectively. Statistical analysis showed that there was no significant difference in levels of early, late, and total apoptosis in the Blank and siCon groups. Compared with the Blank and siCon groups, the proportion of early, late, and total apoptosis in the siARHGEF10 group increased significantly (Figure 6A–D).

Figure 6. Apoptosis detection in SH-SY5Y cells by flow cytometry assay. Analysis of apoptosis in the Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 cells. Cells that were propidium iodide (PI)- and Annexin V-negative were considered alive. Cells that were either Annexin V- or PI-positive were considered early or late apoptotic. Cells that were PI- and Annexin V-positive were considered necrotic. PI-negative or cells were either untreated (Blank), treated with control siRNA (siCon), or treated with anti-ARHGEF10 siRNA (siARHGEF10). ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001

-

In the current study, we used zebrafish for our model. We observed the arhgef10 expression pattern in the early stages of development and showed that arhgef10 was expressed in the midbrain and hindbrain 36−72 hpf, while arhgef10 was expressed in the hematopoietic system 36 and 48 hpf. The locomotor capacity and response ability of arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− zebrafish larvae decreased significantly compared to wild-type larvae, and the phenotype was more severe in arhgef10−/− larvae. Knockdown of ARHGEF10 in human neuroblastoma cells led to decreased cell proliferation and increased cell apoptosis. These results suggested that ARHGEF10 has a haploinsufficiency effect.

According to previous studies, a single allelic mutation [g.63687C>T (p.Thr332Ile)] of ARHGEF10 could lead to thinning of the human peripheral nerve axon myelin sheath and reduction of nerve conduction[16, 24, 25] in an autosomal dominant manner. In addition, ARHGEF10, rs9657362 (c.1110G > C, p.Leu370Phe), rs2294039 (c.2098G > A, p.Val700Ile), and rs17683288 (c.2950T > G, p.Ser984Ala) SNPs may lead to increased susceptibility to chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurologic diseases[26, 32, 33]. Notably, SNP rs11136442 (c.2144-2288G > A) may increase the risk of schizophrenia[27]. All of these mutations or SNPs were associated with symptoms involving the peripheral nervous system; however, knocking out Arhgef10 in mice leads to autism-like phenotypes, social interaction disorders, hyperactivity, depression, and anxiety behaviors[28], which mainly affect the central nervous system. Therefore, arhgef10 may have a haploinsufficient effect and has a role in development of the nervous system. Our results demonstrated that arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− zebrafish had decreased exercise capacity and stress ability, but arhgef10−/− zebrafish had a more severe phenotype, thus providing more direct experimental evidence that arhgef10 had a haploinsufficient effect.

In addition to expression in the nervous system, arhgef10 was also expressed in the hematopoietic system of zebrafish. Previous studies have shown that mutations of this gene could affect the hematopoietic system[34, 35]. The hematopoietic system of Arhgef10−/− mice was abnormal and the platelet aggregation response to thrombin, collagen, and ADP stimulation is prolonged[35]. Thrombin stimulation caused by platelet clot contraction is weakened and the tail bleeding time is prolonged[35]. In humans, the following SNPs of ARHGEF10 may increase the risk of ischemic stroke[36-38]: rs2280887 (c.1968-1697C > G); rs4376531 (c.1967+936C > A); and rs4480162 (c.1967+933G > C). The SNP, rs2280885 (c.961-526T > C), may cause an increase in serum triglyceride levels[36]. Because actin-myosin contraction is activated by phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC), when homozygous Arhgef10 is deleted, activity of RhoA decreases and inhibits MLC phosphorylation through the RhoA-ROCK-MLC axis, thus interfering with rearrangement of the cytoskeleton after platelet activation[35, 37]. In this study, the blood of zebrafish could not be collected, so the phenotype of one copy loss was not confirmed.

In cancer, the copy number loss of ARHGEF10 cooperates with KRAS to promote the occurrence of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)[38]. The expression of ARHGEF10 is reduced in > 70% of PDAC cell lines, and the copy number loss exists in > 30% of PDAC patient-derived xenografts[38]. In addition, ARHGEF10 suppresses tumors. Specifically, in Hela cells ARHGEF10 is located in vesicles, which contain Rab6 and Rab8 and the secreted marker neuropeptide Y (NPY), Venus[39]. In the breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB231, weakened cell invasion occurs after knocking down the expression of ARHGEF10 [39]. Knockout of ARHGEF10 by siRNA impairs the localization of Rab8 in these extracellular vesicles. In addition, ARHGEF10 knockout in MDA-MB231 cells significantly weakens the invasiveness accompanied by decreased Rab8. Based on these results, it can be inferred that ARHGEF10 plays a role in exocytosis and tumor invasion in a Rab8-dependent manner[25, 39]. After we knocked down the expression of ARHGFE10 by siRNA in human neuroblastoma cells, the cell proliferation decreased and apoptosis increased. The previous study may explain the mechanism underlying knockdown of ARHGEF10 with interfering RNA in HeLa cells led to the formation of multipolar spindles in the M phase. Abnormal centriole replication and cytokinesis induced the formation of multinuclei, resulting in the inability of cells to divide and proliferate normally[40]. Because the single-copy deletion of ARHGEF10 can be detected during prenatal diagnosis, the clinical significance is not clear. Our research showed that the single-copy deletion of ARHGEF10 in zebrafish can lead to abnormal development of the nervous system, suggesting that a single-copy deletion of this gene may be pathogenic, providing some important information for clinical genetic counseling.

In summary, the ARHGEF10 gene may be dosage-sensitive. Single-copy loss of ARHGEF10 can induce central nervous system symptoms. There are few studies on ARHGEF10 at the molecular level, and the mechanism is still unclear, which calls for more in-depth research. Elucidation of molecular mechanism might play a pivotal role in understanding the function and significance of ARHGEF10 and its family members.

-

ARHGEF10 appears to be haploinsufficient; however, the phenotype and underlying mechanism in humans warrants further research.

-

The study was conceived by ZHANG Yi and TIAN Chan. TIAN Chan designed and supervised the study. ZHANG Yi performed the experiments. AN Ming Xing provided homozygous identification assistance. ZHANG Yi and TIAN Chan wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors. GONG Chen, WANG Yu Tong, LI Yang Yang, and LIN Meng contributed to the data collection. LI Rong took part in the design of the work, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

doi: 10.3967/bes2022.005

Single-copy Loss of Rho Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor 10 (arhgef10) Causes Locomotor Abnormalities in Zebrafish Larvae

-

Abstract:

Objective To determine if ARHGEF10 has a haploinsufficient effect and provide evidence to evaluate the severity, if any, during prenatal consultation. Methods Zebrafish was used as a model for generating mutant. The pattern of arhgef10 expression in the early stages of zebrafish development was observed using whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH). CRISPR/Cas9 was applied to generate a zebrafish model with a single-copy or homozygous arhgef10 deletion. Activity and light/dark tests were performed in arhgef10−/−, arhgef10+/−, and wild-type zebrafish larvae. ARHGEF10 was knocked down using small interferon RNA (siRNA) in the SH-SY5Y cell line, and cell proliferation and apoptosis were determined using the CCK-8 assay and Annexin V/PI staining, respectively. Results WISH showed that during zebrafish embryonic development arhgef10 was expressed in the midbrain and hindbrain at 36–72 h post-fertilization (hpf) and in the hemopoietic system at 36–48 hpf. The zebrafish larvae with single-copy and homozygous arhgef10 deletions had lower exercise capacity and poorer responses to environmental changes compared to wild-type zebrafish larvae. Moreover, arhgef10−/− zebrafish had more severe symptoms than arhgef10+/- zebrafish. Knockdown of ARHGEF10 in human neuroblastoma cells led to decreased cell proliferation and increased cell apoptosis. Conclusion Based on our findings, ARHGEF10 appeared to have a haploinsufficiency effect. -

Key words:

- arhgef10 /

- Zebrafish /

- CRISPR/Cas9 /

- Haploinsufficiency /

- Copy loss

-

Figure 1. Detection of arhgef10 expression during early embryogenesis in wild-type zebrafish. (A–H) Wild-type embryos after whole-mount in situ hybridization using an antisense probe for arhgef10 at the indicated developmental stages. The red arrow points to high expression of arhgef10 in the hemopoietic system. The red circle indicates high expression of arhgef10 in the midbrain and hindbrain of zebrafish larvae.

Figure 2. Generation of the arhgef10 deletion model in zebrafish by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. (A) Sketch map of the zebrafish arhgef10 gene and protein. The CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutation (121-base deletion and 16-base insertion) in arhgef10 is shown in the annotated arhgef10 mutant sequences. The nucleotides in red are inserted sequences and “-” are deleted nucleotides. (B) Identification of the copy number losses model by PCR. The PCR product for wild-type was 261 bp and for the ahrgef10 deletion was 140 bp. (C) The relative expression of arhgef10 mRNA in the brains of arhgef10+/+, arhgef10+/−

, and arhgef10−/− larvae 5 dpf (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001, respectively). Figure 3. Spontaneous activity of wild type, arhgef10+/− and arhgef10−/− larvae 5 dpf. (A) Distance traveled in 60 min 5 dpf. (B) Average distance moved per minute 5 dpf. (C) Movement time during 60 min 5 dpf. The vertical axis shows the normalized distance (mm) traveled by larvae in each 1-min bin. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; n = 20 for each genotype).

Figure 4. Light-to-dark test of wild-type, arhgef10+/−, and arhgef10−/− larvae 5 dpf. (A) The program of the test. The activity was recorded during 30 min of light (L0) and 2.5 cycle of 5 min light-to-dark intervals [5 min dark (D1) – 5 min light (L1) – 5 min dark (Ds2) – 5 min light (L2) – 5 min dark (D3)]. (B) The average distance moved per min in each light or dark period 5 dpf. The vertical axis shows the normalized distance (mm) traveled by larvae in each 1-min bin. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001; n = 20 for each genotype).

Figure 5. Expression analysis of proteins in SH-SY5Y cells and cell proliferation in the ARHGEF10 knockdown SH-SY5Y cell line. (A) Western blot analysis of ARHGEF10 protein expression in Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 cells. (B) Quantitative analysis of ARHGEF10 protein in Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 cells. (C) The cell viability was measured at 24, 48, and 72 h after transfection by the CCK-8 assay. Cells were untreated (Blank), treated with control siRNA (siCon), or anti-ARHGEF10 siRNA (siARHGEF10). The visualized protein signals were transferred to quantitative expression by ImageJ software. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). ns, no statistical differences; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 6. Apoptosis detection in SH-SY5Y cells by flow cytometry assay. Analysis of apoptosis in the Blank, siCon, and siARHGEF10 cells. Cells that were propidium iodide (PI)- and Annexin V-negative were considered alive. Cells that were either Annexin V- or PI-positive were considered early or late apoptotic. Cells that were PI- and Annexin V-positive were considered necrotic. PI-negative or cells were either untreated (Blank), treated with control siRNA (siCon), or treated with anti-ARHGEF10 siRNA (siARHGEF10). ns P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001

Table 1. gRNA for gene-specific editing of arhgef10 exons 12 and 13

gRNA Sequences (5’– 3′) ahgef10-exon12-1 GAAACACCACCTTACGCTTG ahgef10-exon12-2 ATCCCAGTCAGATACTCTGC ahgef10-exon13-1 AGCGTCCAACACCATAGACT ahgef10-exon13-2 GTCCAGGAAACAGGGTTTAG -

[1] Sahoo T, Dzidic N, Strecker MN, et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis of pregnancy loss by chromosomal microarrays: outcomes, benefits, and challenges. Genet Med, 2017; 19, 83−9. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.69 [2] Levy B, Sigurjonsson S, Pettersen B, et al. Genomic imbalance in products of conception: single-nucleotide polymorphism chromosomal microarray analysis. Obstet Gynecol, 2014; 124, 202−9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000325 [3] Shi SS, Lin SB, Chen BJ, et al. Isolated chromosome 8p23. 2-pter deletion:novel evidence for developmental delay, intellectual disability, microcephaly and neurobehavioral disorders. Mol Med Rep, 2017; 16, 6837−45. [4] Hagens O, Minina E, Schweiger S, et al. Characterization of FBX25, encoding a novel brain-expressed F-box protein. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2006; 1760, 110−8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.09.018 [5] Harich B, Klein M, Ockeloen CW, et al. From man to fly - convergent evidence links FBXO25 to ADHD and comorbid psychiatric phenotypes. J Child Psychol Psychiat, 2020; 61, 545−5. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13161 [6] Ranta S, Zhang YH, Ross B, et al. The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses in human EPMR and mnd mutant mice are associated with mutations in CLN8. Nat Genet, 1999; 23, 233−6. doi: 10.1038/13868 [7] Ranta S, Topcu M, Tegelberg S, et al. Variant late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in a subset of Turkish patients is allelic to Northern epilepsy. Hum Mutat, 2004; 23, 300−5. doi: 10.1002/humu.20018 [8] Reinhardt K, Grapp M, Schlachter K, et al. Novel CLN8 mutations confirm the clinical and ethnic diversity of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Clin Genet, 2010; 77, 79−85. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01285.x [9] Guo JY, Johnson GS, Cook J, et al. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in a german shorthaired pointer associated with a previously reported CLN8 nonsense variant. Mol Genet Metab Rep, 2019; 21, 100521. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2019.100521 [10] Guo JY, Johnson GS, Brown HA, et al. A CLN8 nonsense mutation in the whole genome sequence of a mixed breed dog with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis and Australian Shepherd ancestry. Mol Genet Metab, 2014; 112, 302−9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.05.014 [11] Lonka L, Aalto A, Kopra O, et al. The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis Cln8 gene expression is developmentally regulated in mouse brain and up-regulated in the hippocampal kindling model of epilepsy. BMC Neurosci, 2005; 6, 27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-6-27 [12] Adhikari B, De Silva B, Molina JA, et al. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis related ER membrane protein CLN8 regulates PP2A activity and ceramide levels. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2019; 1865, 322−8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.11.011 [13] Allen NM, O'HIci B, Anderson G, et al. Variant late-infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis due to a novel heterozygous CLN8 mutation and de novo 8p23. 3 deletion. Clin Genet, 2012; 81, 602−4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01777.x [14] Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature, 2003; 421, 231−7. doi: 10.1038/nature01278 [15] Li JM, Lu CL, Cheng MC, et al. Role of the DLGAP2 gene encoding the SAP90/PSD-95-associated protein 2 in schizophrenia. PLoS One, 2014; 9, e85373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085373 [16] Verhoeven K, De Jonghe P, Van De Putte T, et al. Slowed conduction and thin myelination of peripheral nerves associated with mutant rho Guanine-nucleotide exchange factor 10. Am J Hum Genet, 2003; 73, 926−32. doi: 10.1086/378159 [17] Zheng Y. Dbl family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Trends Biochem Sci, 2001; 26, 724−32. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01973-9 [18] Jin SC, Lewis SA, Bakhtiari S, et al. Mutations disrupting neuritogenesis genes confer risk for cerebral palsy. Nat Genet, 2020; 52, 1046−56. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0695-1 [19] Barbosa S, Greville-Heygate S, Bonnet M, et al. Opposite modulation of RAC1 by mutations in TRIO is associated with distinct, domain-specific neurodevelopmental disorders. Am J Hum Genet, 2020; 106, 338−55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.01.018 [20] De Filippis B, Valenti D, Chiodi V, et al. Modulation of Rho GTPases rescues brain mitochondrial dysfunction, cognitive deficits and aberrant synaptic plasticity in female mice modeling Rett syndrome. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 2015; 25, 889−901. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.03.012 [21] Van Der Bijl I, Nawaz K, Kazlauskaite U, et al. Reciprocal integrin/integrin antagonism through kindlin-2 and Rho GTPases regulates cell cohesion and collective migration. Matrix Biol, 2020; 93, 60−78. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2020.05.005 [22] Hiraide T, Kaba Yasui H, Kato M, et al. A de novo variant in RAC3 causes severe global developmental delay and a middle interhemispheric variant of holoprosencephaly. J Hum Genet, 2019; 64, 1127−32. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0656-7 [23] Droppelmann CA, Campos-Melo D, Volkening K, et al. The emerging role of guanine nucleotide exchange factors in ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci, 2014; 8, 282. [24] Nelis E, De Jonghe P, De Vriendt E, et al. Mutation analysis of the nerve specific promoter of the peripheral myelin protein 22 gene in CMT1 disease and HNPP. J Med Genet, 1998; 35, 590−3. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.7.590 [25] Chaya T, Shibata S, Tokuhara Y, et al. Identification of a negative regulatory region for the exchange activity and characterization of T332I mutant of Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 10 (ARHGEF10). J Biol Chem, 2011; 286, 29511−20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236810 [26] Beutler AS, Kulkarni AA, Kanwar R, et al. Sequencing of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease genes in a toxic polyneuropathy. Ann Neurol, 2014; 76, 727−37. doi: 10.1002/ana.24265 [27] Jungerius BJ, Hoogendoorn MLC, Bakker SC, et al. An association screen of myelin-related genes implicates the chromosome 22q11 PIK4CA gene in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry, 2008; 13, 1060−8. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002080 [28] Lu DH, Liao HM, Chen CH, et al. Impairment of social behaviors in Arhgef10 knockout mice. Mol Autism, 2018; 9, 11. doi: 10.1186/s13229-018-0197-5 [29] Li XD, Tu HW, Hu KQ, et al. Effects of toluene on the development of the inner ear and lateral line sensory system of zebrafish. Biomed Environ Sci, 2021; 34, 110−8. [30] Jowett T. Analysis of protein and gene expression. Methods Cell Biol, 1999; 59, 63−85. [31] Chang NN, Sun CH, Gao L, et al. Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Res, 2013; 23, 465−72. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.45 [32] Chen YZ, Fang F, Kidwell KM, et al. Genetic variation in Charcot-Marie-Tooth genes contributes to sensitivity to paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pharmacogenomics, 2020; 21, 841−51. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2020-0053 [33] Yamashita Y, Irie K, Kochi A, et al. Involvement of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease gene mitofusin 2 expression in paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia in rats. Neurosci Lett, 2017; 653, 337−40. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.05.069 [34] Lundbäck V, Kulyté A, Arner P, et al. Genome-wide association study of Diabetogenic Adipose Morphology in the GENetics of Adipocyte Lipolysis (GENiAL) cohort. Cells, 2020; 9, 1085. doi: 10.3390/cells9051085 [35] Lu DH, Hsu CC, Huang SW, et al. ARHGEF10 knockout inhibits platelet aggregation and protects mice from thrombus formation. J Thromb Haemost, 2017; 15, 2053−64. doi: 10.1111/jth.13799 [36] De Toro-Martín J, Guénard F, Rudkowska I, et al. A common variant in ARHGEF10 alters delta-6 desaturase activity and influence susceptibility to hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Lipidol, 2018; 12, 311−20.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2017.10.020 [37] Zee RYL, Wang QM, Chasman DI, et al. Gene variations of ROCKs and risk of ischaemic stroke: the Women's Genome Health Study. Clin Sci (Lond), 2014; 126, 829−35. doi: 10.1042/CS20130652 [38] Joseph J, Radulovich N, Wang T, et al. Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor ARHGEF10 is a putative tumor suppressor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene, 2020; 39, 308−21. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0985-1 [39] Shibata S, Kawanai T, Hara T, et al. ARHGEF10 directs the localization of Rab8 to Rab6-positive executive vesicles. J Cell Sci, 2016; 129, 3620−34. [40] Aoki T, Ueda S, Kataoka T, et al. Regulation of mitotic spindle formation by the RhoA guanine nucleotide exchange factor ARHGEF10. BMC Cell Biol, 2009; 10, 56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-56 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links