-

Aeromonas spp. are important human opportunistic pathogens that can cause intestinal and extra-intestinal diseases, particularly in immunocompromized individuals, including gastroenteritis, wound infections, and even life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis[1]. Aeromonas species are often isolated from freshwater, seafood, and meat products[2-3] and are therefore a primary cause of food contamination and may act as intermediaries in transmitting disease to humans[4].

The Aeromonas genus contains over 26 species and has a very complex taxonomy. Although great efforts have been made to correctly identify different Aeromonas species, particularly those related to human diseases, this has been difficult to achieve using traditional biochemical methods due to taxonomic complexity[1,5]. In addition, conventional biochemical methods such as matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) are time consuming and tedious for routine use. Moreover, the 16S rDNA sequence used for bacterial identification has high between-species similarity and thus cannot adequately distinguish between Aeromonas species[6-7]. Recently studies have shown that housekeeping gene sequencing (gyrB and rpoD) can be used for the phylogenetic analysis and identification of Aeromonas species[8-9]; for instance, Yano et al.[10] used housekeeping gene sequencing to identify 87 Aeromonas strains at the species level.

The pathogenesis of Aeromonasspp. involves a series of virulence factors[11]. These include hemolytic toxins such as aerolysin-related cytotoxic enterotoxin (Act)[12], heat-labile cytotonic enterotoxin (Alt), hemolysin (hlyA), heat-stable cytotonic toxins (Ast)[13], and aerolysin (aerA)[14]. In addition, the type III secretion system (TTSS), lateral flagella (laf), polar flagellum (fla)[15-16], elastase (ela)[17], and lipase (lip)[18] also contribute toward the pathogenicity of Aeromonas.

Aeromonas antibiotic resistance has increased globally in recent years; for example, some strains are resistance to aminoglycosides [aac(6’)-Ib], while others harbor plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) determinants[19]. In Aeromonas isolates from South Africa and Korea, the prevalence of aac(6’)-Ib was found to be 29.23% and 29.00%, respectively[19-20]. The important PMQR determinant qnrS has been reported in Aeromonas[21-22], with 73.85% of Aeromonas strains in Korea found to harbor qnrS genes[19]. Conversely, qnrS was found to be present in 21.00% of Aeromonas isolates from freshwater fish in South Africa[20]. The resistance of Aeromonas to several different classes of antibiotics poses a major problem for human health since the resistant bacteria can be transmitted from the aquatic environment to humans via the food chain or direct contact[23]. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor Aeromonas antimicrobial resistance to guide clinical treatment.

In this study, we evaluated the characteristics of Aeromonas strains isolated from environmental sources, food, and clinical patients in Ma’anshan, Anhui province, China. In addition, we investigated the virulence-associated genes and antimicrobial resistance of these Aeromonasspp.

-

Fecal samples and bodily fluids were acquired from patients who had provided informed consent. This study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

In 2018, 90 Aeromonas isolates were obtained from 33 stool samples from patients with diarrhea, 36 tap water systems, and 21 foods in Ma’anshan Anhui Province, China (Figure 1). The isolated strains were identified using an automatic bacteriologic analyzer (Vitek 2 Compact, BioMerieuX). Bacteria were cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plates overnight at 37 °C.

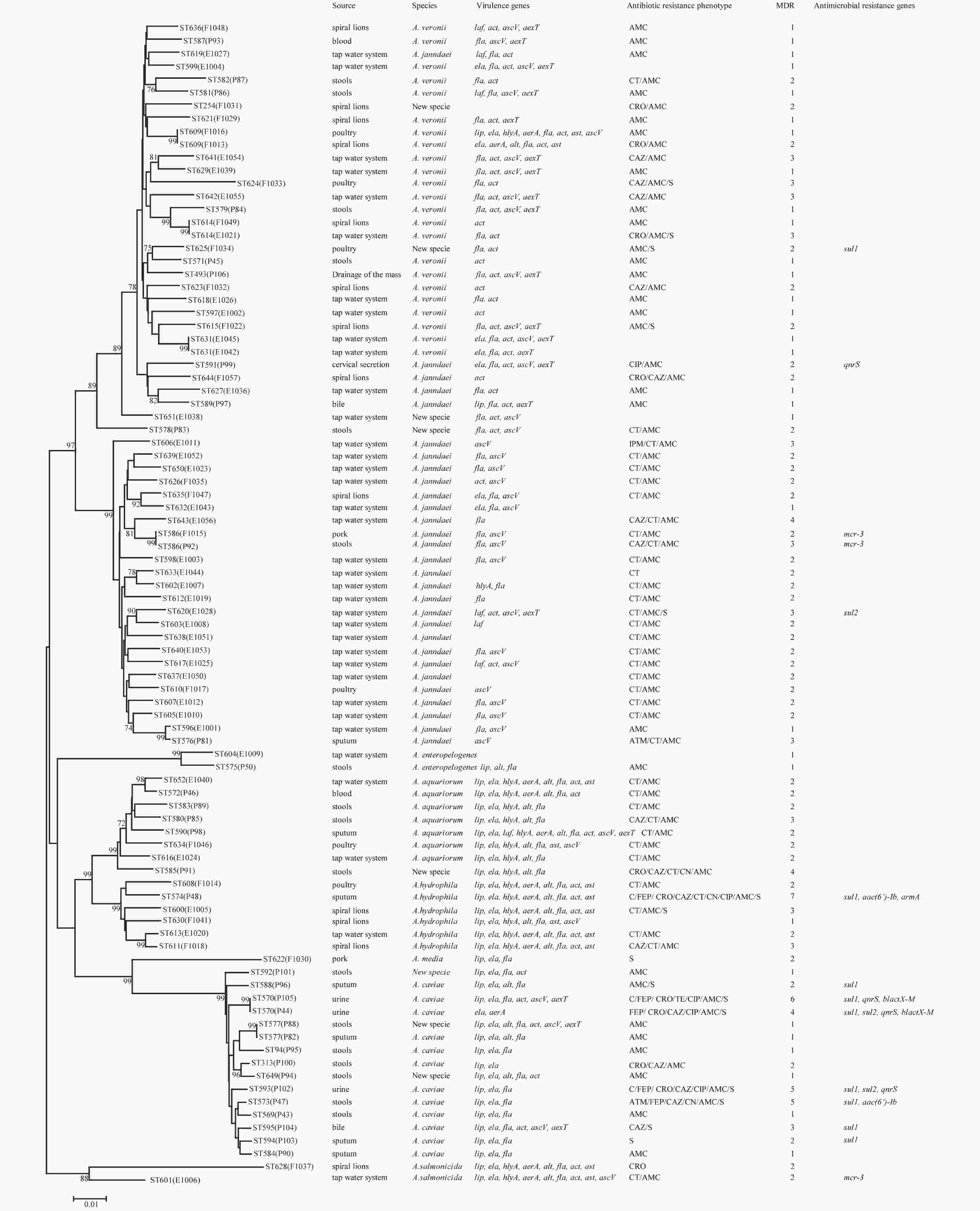

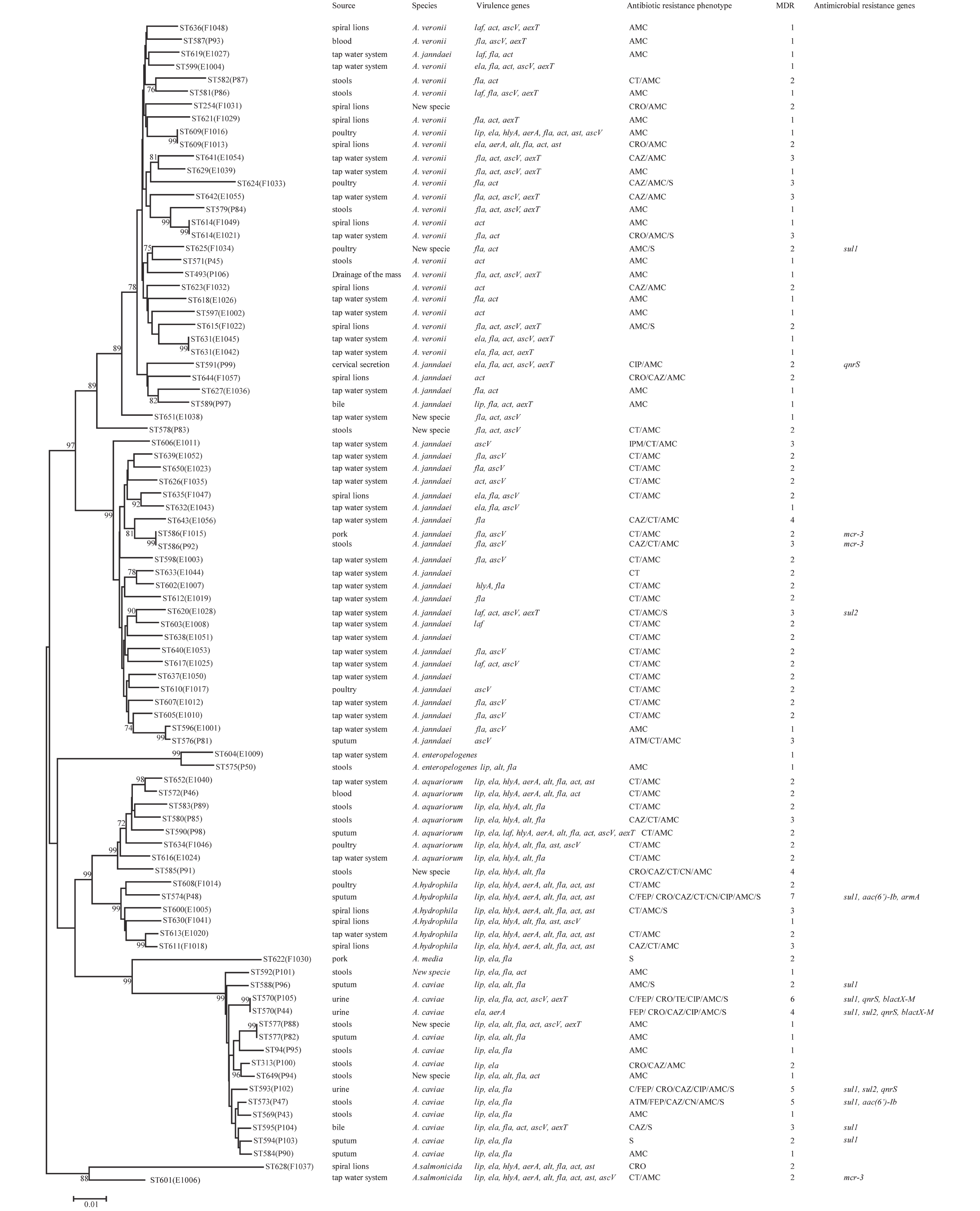

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships were determined using the concatenated sequences of six genes included in this study. The source, species, virulence genes, antibiotic resistance phenotype, MDR (number of drugs resistant to), and antimicrobial resistance genes of the Aeromonas isolates are shown on the right. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using a neighbor-joining algorithm. ST: sequence type.

-

To analyze the subtype of the Aeromonas isolates, we used the Aeromonas MLST scheme (http://pubmlst.org/Aeromonas/) with six housekeeping genes: gyrB, groL, gltA, metG, ppsA, and recA. PCR was carried out using previously described primers and protocols[5]. The sequences of the six loci were compared to those published in the Aeromonas MLST database, as well as the STs. New alleles and STs were submitted to the Aeromonas MLST database for name assignment.

In this study, 90 Aeromonas strains were identified at the species level by analyzing the housekeeping genes gyrB and cpn60[8,24]. The reference nucleotide sequences of these genes were taken from the GenBank database and included the 28 representative species listed in Supplementary Table S1 (available in www.besjournal.com). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in Clustal-W[25]. All primers were synthesized by Beijing Tsingke Biological Technology Company (Beijing, China).

Table S1. The gyrB and cpn60 genes of twenty-eight representative Aeromonas species available in GenBank

Strains Species name GenBank locus gyrB cpn60 A.allosaccharophila-CECT4200 A. allosaccharophila AY101823 EU741624 A.bestiarum-112A A. bestiarum JN711733 EU741625 A.bestiarum-628A A. bestiarum JN711738 EU306797 A.bivalvium-665N A. bivalvium EF465524 EU306798 A.bivalvium-868E A. bivalvium EF465525 EU306799 A.caviae-CECT838 A. caviae JN829497 EU306800 A.encheleia-CECT4342 A. encheleia JN829499 EU306801 A.enteropelogenes-CECT4487 A. enteropelogenes EF465526 EU306837 A.eucrenophila-CECT4224 A. eucrenophila JN829501 EU306803 A.eucrenophila-CECT4854 A. eucrenophila AY101813 EU741634 A.hydrophila-CECT5236 A. hydrophila JN711791 EU741635 A.allosaccharophila-CECT4199 A. allosaccharophila JN829495 EU306795 A.aquariorum-MDC317 A. aquariorum HQ442717 JN711581 A.aquariorum-MDC573 A. aquariorum HQ442715 JN711582 A.aquariorum-MDC47 A. aquariorum EU268444 FJ936120 A.caviae-A4EL5 A. caviae JF938610 JF920575 A.caviae-E7EL42 A. caviae JF938613 JF920578 A.diversa-CECT4254 A. diversa JN829523 EU306835 A.diversa-CECT5178 A. diversa GU062401 GQ365713 A.encheleia-CECT4253 A. encheleia JN829522 EU306802 A.enteropelogenes-CECT4255 A. enteropelogenes JN829517 EU306836 A.fluvialis-717 A. fluvialis FJ603455 GU062398 A.hydrophila-AP60 A. hydrophila JF938654 JF920619 A.hydrophila-CECT839 A. hydrophila JN711776 EU306804 A.hydrophila-CF38 A. hydrophila JF938658 JF920623 A.jandaei-ATCC49568 A. jandaei FN706559 AY922357 A.jandaei-CECT4228 A. jandaei JN829507 EU306807 A.media-CECT4234 A. media KP400958 EU741641 A.media-CECT4232 A. media JN829508 EU306808 A.molluscorum-431E A. molluscorum EF465520 EU306810 A.molluscorum-848T A. molluscorum AM179827 EU306811 A.piscicola-R94 A. piscicola JN711768 JN711540 A.piscicola-S1.2 A. piscicola JN711765 GU062399 A.popoffii-LMG17541 A. popoffii JN711769 EU306814 A.salmonicida-CECT5173 A. salmonicida JN711837 EU741642 A.salmonicida-621A A. salmonicida JN711829 EU306819 A.salmonicida-856T A. salmonicida JN711833 EU306823 A.sanarellii-A2-67 A. sanarellii FJ807277 JN215527 A.sanarellii-E4P29 A. sanarellii JF938619 JF920584 A.sharmana-DSM17445 A. sharmana EF465528 EU306831 A.simiae-CIP107797 A. simiae AJ632225 EU306832 A.simiae-CIP107798 A. simiae JN829555 EU306833 A.sobria-CECT4245 A. sobria JN829516 EU306834 A.taiwanensis-A2-50 A. taiwanensis FJ807272 JN215528 A.veronii-AT46 A. veronii JF938687 JF920652 A.veronii-AT48 A. veronii JF938688 JF920653 A.veronii-CECT4257 A. veronii HQ442728 EU306838 A.veronii-CECT4486 A. veronii EF465527 EU306841 A.rivuli-CECT7518 A. rivuli CDBJ01000001 JN215526 A.schubertii-BT3-772 A. schubertii LC003078 LC003165 A.schubertii-BT3-777 A. schubertii LC003081 LC003168 A.tecta-CECT7082 A. tecta JN829521 NZ_CDCA01000043 A.cavernicola-MDC2508 A. cavernicola PGGC01000001 PGGC01000001 A.lusitana-MDC2473 A. lusitana PGCP01000001 PGCP01000001 -

To detect virulence-associated genes in the Aeromonas isolates, we performed PCR using previously described alt, ast, hlyA, aerA, act, ascV, aexT, laf, lip, fla, and ela primers. PCR amplification was performed in a 50 μL reaction volume containing 25 μL of Taq PCR MasterMix (Takara Bio, Inc., Japan), 1 μL of 10 μmol/L primer, 21 μL of ddH2O, and 2 μL of DNA template under the following cycling conditions: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55–60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final cycle at 72 °C for 5 min. Positive PCR products were confirmed by sequencing, detecting a total of 11 virulence-associated genes.

-

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were carried out using the broth microdilution method according to CLSI guidelines (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2018). The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the following 13 antibiotics were measured: amoxicillin/clavulanate (AMC), ampicillin (AMP), cefepime (FEP), ceftriaxone (CRO), ceftazidime (CAZ), imipenem (IPM), aztreonam (ATM), gentamycin (GEN), tetracycline (TCY), ciprofloxacin (CIP), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT), chloramphenicol (CHL), and colistin (CT). E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as the quality-control strain for susceptibility testing.

-

To detect antimicrobial resistance genes, we performed PCR amplification on tetracycline resistance (tetA, tetB, and tetE), extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) (blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX)[19], aminoglycoside resistance [armA, aphAI-IAB, aac(6’)-Ib, and aac(3)-IIa][26], sulphonamide resistance (sul1and sul2)[27], and mobile colistin resistance (mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, and mcr-4) genes, as well as PMQR (qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS) genes[19] using previously described primers and protocols (Table 1)[19,28-32]. Positive PCR products were confirmed by sequencing.

Table 1. Primer sequences used to amplify antimicrobial resistance genes

Targeted gene Primers Sequence (5’→3’) Product size (bp) ESBL blaTEM blaTEM-F ATAAAATTCTTGAAGACGAAA 1,080 blaTEM-R GACAGTTACCAATGCTTAATC blaSHV blaSHV-F TTATCTCCCTGTTAGCCACC 795 blaSHV-R GATTTGCTGATTTCGCTCGG blaCTX-M blaCTX-M-F CGCTTTGCGATGTGCAG 550 blaCTX-M-R ACCGCGATATCGTTGGT Tetracycline resistance tetA tetA-F GTAATTCTGAGCACTGTCGC 1,000 tetA-R CTGCCTGGACAACATTGCTT tetB tetB-F CTCAGTATTCCAAGCCTTTG 400 tetB-R CTAAGCACTTGTCTCCTGTT tetE tetE-F GTGATGATGGCACTGGTCAT 1,100 tetE-R CTCTGCTGTACATCGCTCTT PMQR qnrA qnrA-F AGAGGATTTCTCACGCCAGG 580 qnrA-R TGCCAGGCACAGATCTTGAC qnrB qnrB-F GATCGTGAAAGCCAGAAAGG 496 qnrB-R ACGATGCCTGGTAGTTGTCC qnrS qnrS-F GCAAGTTCATTGAACAGGGT 428 qnrS-R TCTAAACCGTCGAGTTCGGCG Aminoglycoside resistance armA armA-F AGGTTGTTTCCATTTCTGAG 591 armA-R TCTCTTCCATTCCCTTCTCC aphAI-IAB aphAI-IAB-F AAACGTCTTGCTCGA GGC 500 aphAI-IAB-R CAAACCGTTATTCATTCGTGA aac(3)-IIa aac(3)-IIa-F ATGGGCATC ATTCGCACA 749 aac(3)-IIa-R TCTCGGCTTGAACGAATTGT aac(6’)-Ib aac(6’)-Ib-F TTGCGATGCTCTATGAGTGGCTA 482 aac(6’)-Ib-R CTCGAATGCCTGGCGTGTTT MCR mcr-1 mcr-1-F CGGTCAGTCCGTTTGTTC 309 mcr-2-R CTTGGTCGGTCTGTAGGG mcr-2 mcr-2-F TGTTGCTTGTGCCGATTGGA 567 mcr-2-R CAGCAACCAACAATACCATCT mcr-3 mcr-3-F AGTTTGGTTTCGCCATTTCATTAC 1,084 mcr-3-R ATATCACTGCGTGGACAGTCAGG mcr-4 mcr-4-F TTACAGCCAGAATCATTATCA 488 mcr-4-R ATTGGGATAGTCGCCTTTTT Sulfonamide resistance sul1 sul1-F CGGCGTGGGCTACCTGAACG 433 sul1-R GCCGATCGCGTGAAGTTCCG sul2 sul2-F GCGCTCAAGGCAGATGGCATT 293 sul2-R GCGTTTGATACCGGCACCCGT -

The 90 Aeromonas isolates were divided into 84 STs of which 80 were novel (ST569-ST644 and ST649-ST652), indicating high genetic diversity. No STs were predominant.

-

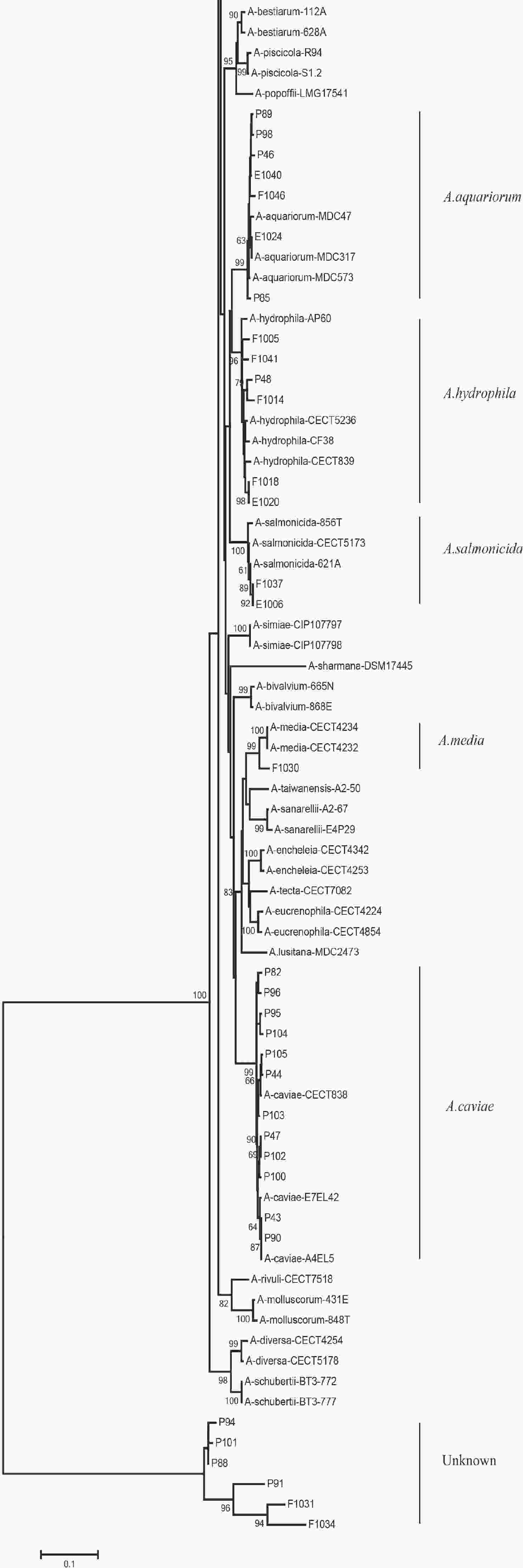

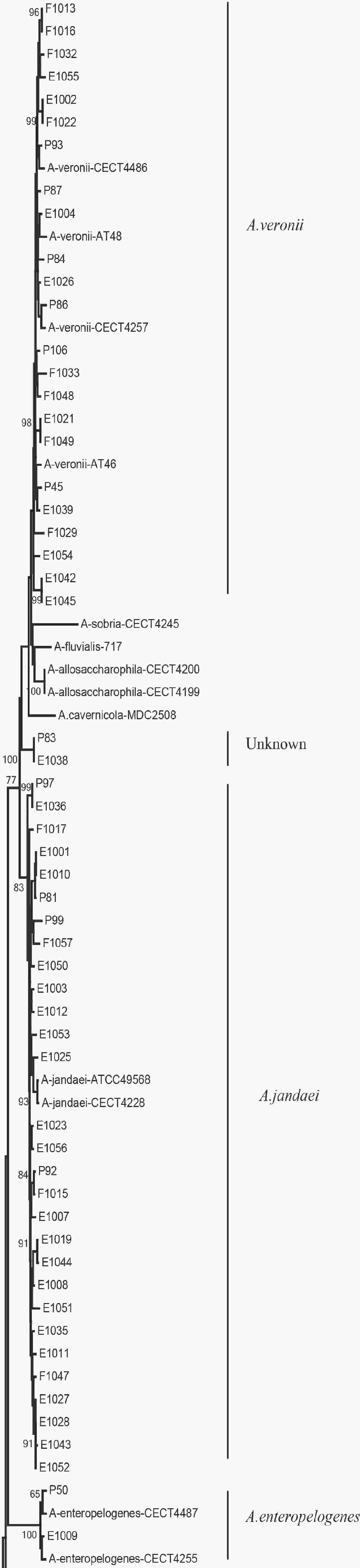

We evaluated the phylogeny of the 90 Aeromonas isolates based on their gyrB and cpn60 sequences (Figure 2). Sequencing analysis classified 82 (91.1%) of the strains into eight different species, of which the three most common were A. jandaei (32.2%), A. veronii (25.5%), and A. caviae (13.3%). Notably, eight strains did not belong to any of the 28 known species and may be regarded as new species. In addition, the distribution of Aeromonas species isolated from clinical patients, food, and tap water samples varied (Table 2). A. caviae (36.4%) was the most prevalent species in clinical isolates, A. veronii (18.1%) was the most common in food isolates, and A. jandaei (58.3%) was the most prevalent in environmental isolates, with the of these three species differing significantly between patient-, food-, and environment-derived isolates (P < 0.05, χ2 test).

Figure 2. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using the concatenated sequences of the gyrB and cpn60 genes, revealing the relationships between the 90 Aeromonas isolates from clinical patients, tap water systems, and food from Ma’anshan Anhui Province, China. Numbers on or near the nodes represent bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates. Isolates were designated as either P, E, or F to indicate strains isolated from clinical patients, tap water systems (environment), or food, respectively.

Table 2. Distribution of Aeromonas spp. in isolates collected from clinical patients, food, and tap water samples

Species Total strains (n, %) Clinical isolates (n, %) Environmental isolates (n, %) Food isolates (n, %) A. veronii 23 (25.5) 6 (18.1) 9 (25.0) 8 (38.1) A. caviae 12 (13.3) 12 (36.4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) A. aquariorum 7 (7.8) 4 (12.1) 2 (5.6) 1 (4.8) A. hydrophila 6 (6.7) 1 (3.0) 1 (2.8) 4 (19.0) A. jandaei 29 (32.2) 4 (12.1) 21 (58.3) 4 (19.0) A. enteropelogenes 2 (2.2) 1 (3.0) 1 (2.8) 0 (0.0) A. media 1 (1.1) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (4.8) A. salmonicida 2 (2.2) 0 (0.0) 1 (2.8) 1 (4.8) New species 8 (8.9) 5 (15.1) 1 (2.8) 2 (9.5) Total 90 33 36 21 -

We detected 11 virulence-associated genes in the Aeromonas isolates (Table 3), of which 77.8% carried fla, 52.2% carried act, 44.4% carried ela, and 43.3% carried ascV. Two additional genes, laf and ast, were present in 8.9 and 13.3% of the isolates, respectively. The prevalence of ast, lip, and ela differed significantly in the patient-, food-, and environment- derived isolates (P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test), while only lip and aexT were found to be more prevalent in patient-derived isolates than food-derived or environmental isolates. As shown in Table 4, the 11 virulence-associated genes differed significantly among the most common species. The hemolytic gene act was prevalent in A. hydrophila and A. veronii, whereas the enterotoxin gene alt was prevalent in A. aquariorum and A. hydrophila. The enterotoxin gene ast, hemolytic gene aerA, and hemolytic gene hlyA were more prevalent in A. hydrophila; however, both extracellular protease genes ela and lip were rare in A. jandaei and A. veronii but very common in other species.

Table 3. Distribution of virulence-associated genes in Aeromonas strains isolated clinical patients, food, and tap water samples

Gene Totalstrains (n, %) Clinical strains (n, %) Environmental strains (n, %) Food strains (n, %) act 47 (52.2) 15 (45.5) 18 (50.0) 14 (66.7) alt 22 (24.4) 11 (33.3) 4 (11.1) 7 (33.3) ast 12 (13.3) 1 (3.0) 3 (8.3) 8 (38.1) aerA 13 (14.4) 4 (12.1) 3 (8.3) 6 (28.6) hlyA 19 (21.1) 6 (18.2) 5 (13.9) 8 (33.3) ascV 39 (43.3) 12 (39.4) 19 (52.8) 8 (38.1) aexT 20 (22.2) 10 (30.3) 7 (19.4) 3 (14.3) fla 70 (77.8) 29 (87.9) 26 (72.2) 15 (71.4) lip 34 (37.7) 22 (69.7) 4 (11.1) 8 (38.1) ela 40 (44.4) 22 (66.7) 8 (22.2) 10 (47.6) laf 8 (8.9) 2 (6.1) 4 (11.1) 2 (9.5) Table 4. Distribution of virulence genes in the five most common Aeromonas spp.

Gene A. jandaei (n, %) A. veronii (n, %) A. caviae (n, %) A. aquariorum (n, %) A. hydrophila (n, %) act 8 (27.6) 21 (91.3) 2 (16.7) 3 (42.9) 5 (83.3) alt 0 (0.0) 1 (4.3) 2 (16.7) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) ast 0 (0.0) 2 (8.7) 0 (0.0) 2 (28.6) 6 (100.0) aerA 0 (0.0) 2 (8.7) 1 (8.3) 3 (42.9) 5 (83.3) hlyA 1 (3.4) 2 (8.7) 0 (0.0) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) ascV 18 (62.1) 12 (52.2) 2 (16.7) 2 (28.6) 1 (16.7) aexT 3 (10.3) 13 (56.5) 2 (16.7) 1 (14.3) 0 (0.0) fla 18 (62.1) 18 (78.3) 10 (83.3) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) lip 1 (3.4) 1 (4.3) 11 (91.7) 7 (100) 6 (100.0) ela 3 (10.3) 5 (100.0) 12 (100) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) laf 4 (13.8) 2 (8.7) 0 (0.0) 1 (14.3) 1 (16.7) -

Next, we evaluated the susceptibility of the 90 Aeromonas isolates to 13 antibiotics belonging to ten classes of antibiotic using the broth microdilution method according to CLSI recommendations (Table 5). High ampicillin (100%) and amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid (86.7%) resistance was observed in the Aeromonas strains; however, the majority of the isolates (≥ 90%) were susceptible to aztreonam, imipenem, cefepime, CHL, gentamicin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin. Notably, cefepime and ciprofloxacin resistance were significantly higher in patient isolates than in food or environmental isolates (P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test), whereas only one antibiotic (colistin) displayed significantly higher resistance rates in environmental isolates ( Table 5). Nineteen isolates (21.1%) were found to be multidrug-resistant (MDR), displaying resistance to at least three of the antibiotics tested in this study. Of these 19 MDR isolates, 10 (52.6%) were isolated from patients, 7 (36.8%) were isolated from the environment, and 2 (10.5%) were isolated from food (Figure 1).

Table 5. Prevalence of resistance to different antibiotics

Antibiotics Resistant isolates (n, %) Total strains (n, %) Clinical strains (n, %) Environmental strains (n, %) Food strains (n, %) Penicillins Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 78 (86.7) 31 (96.9) 29 (80.6) 18 (85.7) Ampicillin 90 (100.0) 33 (100.0) 36 (100.0) 21 (100.0) Caphems Cefepime 5 (5.6) 5 (15.6) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Ceftazidime 16 (17.8) 9 (28.1) 3 (8.3) 4 (19.0) Ceftriaxone 11 (12.2) 6 (18.8) 1 (2.8) 4 (19.0) Carbapenems Imipenem 3 (3.3) 1 (3.0) 2 (5.6) 0 (0.0) Monobactams Aztreonam 2 (2.2) 2 (6.1) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Aminoglycosides Gentamicin 3 (3.3) 3 (9.4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Tetracyclines Tetracycline 1 (1.1) 1 (3.1) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Quinolones Ciprofloxacin 5 (5.6) 5 (15.6) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Folate pathway inhibitors Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 15 (16.7) 8 (25.0) 2 (5.6) 5 (23.8) Phenicols Chloramphenicol 3 (3.3) 3 (9.4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Polymyxins Colistin 38 (42.2) 10 (31.2) 21 (58.3) 7 (33.3) -

The PMQR gene qnrS was detected in 4 (4.4%) isolates. The ESBL gene blaCTX-M was detected in 2 (2.22%) isolates. The aminoglycoside resistance genes aac(6’)-Ib and armA were detected in 2 (2.22%) and 1 (1.11%) isolates, respectively. The sulfonamide genes sul1 and sul2 were found in 3 (3.33%) and 9 (10%) isolates, respectively (Figure 1). The mobile colistin resistance gene mcr-3 was detected in 3 (3.33%) isolates. Sequence analysis revealed that one isolate (E1006) harbored mcr-3.25 (GenBank accession no. KM985469.1) while two (P92 and F1015) harbored a new mcr-3 variant which differed from the mcr-3.8 gene by three amino acid changes according to sequence alignment (unpublished data). The ESBL genes blaTEM and blaSHV, aminoglycoside resistance genes aphAI-IAB and aac(3)-IIa, tetracycline resistance genes tetA, tetB, and tetE, colistin resistance genes mcr-1, mcr-2, and mcr-4 genes, and PMQR genes qnrA and qnrB were not detected in any isolates.

-

Aeromonas is a genus of bacteria that are ubiquitously present in aquatic environments and have been linked to infections in both humans and animals[1]. In this study, we evaluated 90 Aeromonas isolates from patients, tap water, and food, and assessed the genetic diversity, putative virulence genes, and antimicrobial resistance of these isolates.

The 90 isolates were separated into 84 STs of which just four were found to match those published in the Aeromonas MLST database, suggesting that 80 were novel (ST569-ST644 and ST649-ST652) and indicating high genetic diversity. We also evaluated the phylogeny of the 90 Aeromonas isolates based on the concatenated gyrB-cpn60 gene sequences (Figure 2), revealing that the isolates were closely related and included A. jandaei (29 isolates), A. veronii (23 isolates), A. caviae (12 isolates), A. aquariorum (7 isolates), A. hydrophila (6 isolates), A. salmonicida (2 isolates), A. enteropelogenes (2 isolates), A. media (1 isolate), and new species (8 isolates). The most common species was A. jandaei, which comprised 32% of all isolates and was mostly isolated from tap water systems. The second most prevalent species was A. veronii, which is distributed in various environments such as water and fish[1]; indeed, some A. veronii strains have been isolated from snail lion, suggesting that this species may be related to invertebrates in aquatic environments. The third most prevalent species was A. caviae, which has previously been shown to have clinical relevance. Zhou et al.[33] reported that the four most prevalent species of Aeromonas in clinical isolates were A. caviae (41.7%), A. veronii (31.3%), A. dhakensis (13.9%), and A. hydrophila (5.2%). Another report[34] about Aeromonas recovered from Patients Suffering from Diarrhea in Israel were evaluated for Aeromonas species, and the most prevalent species were A. caviae (65%) and A. veronii (29%). In this study, the most prevalent species in clinical isolates was A. caviae, accounting for 36.4% of the isolates, followed by A. veronii (18.1%). In brief, the prevalent species of Aeromonas in clinical settings reported in this study is correspond with that reported by other scholars.

The pathogenic mechanism of Aeromonas is complex and multifactorial, which may be related to some of its virulence-associated genes; therefore, we evaluated the virulence-associated genes present in these isolates (Table 3). The enterotoxin and hemolysin genes act, aerA, alt, and ast were present in 47 (52.2%), 13 (14.4%), 22 (24.4%), and 12 (13.3%) of the 90 isolates, respectively. The act gene was detected in 91.3% of A. veronii isolates and 83.3% of A. hydrophila isolates, while the aerA gene was detected in 83.3% of A. hydrophila isolates and 42.9% of A. aquariorum isolates. The alt gene was detected in 100% of A. hydrophila and A. aquariorum strains and 16.7% of A. caviae, whereas the ast gene was present in 28.6% of A. aquariorum strains and all A. hydrophila. The fla, ela, and lip genes were present in 70 (77.8%), 40 (44.4%), and 34 (37.7%) of the 90 isolates, with fla harbored in the majority of species and ela and lip both prevalent in A. aquariorum, A. caviae, and A. hydrophila isolates. The TTSS genes ascV and aexT were detected in 39 (43.3%) and 20 (22.2%) of the 90 isolates, respectively: ascV was present in 62.1% of A. jandaei, 52.2% of A. veronii, and 28.6% of A. aquariorum; while aexT was present in 56.5% of A. veronii and 16.7% of A. caviae. Enterotoxins and hemolysins are very important virulence factors in Aeromonas spp.[35] and many studies have shown a positive correlation between the number of toxin genes harbored by an isolate and its potential virulence[35,13]. The virulence genes detected in this study indicate the potential pathogenicity of the isolates from clinical, food, and environmental sources, as well as their possible risk to human health.

In this study, the majority of Aeromonas strains displayed MDR phenotypes, with 100.0% resistance against amoxicillin and 86.7% resistance against amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid, consistent with previous studies[36,37]. Due to their chromosomal β-lactamase expression, Aeromonas spp. are naturally resistant to β-lactams. As such, the resistance rate of Aeromonas strains derived from patients was significantly higher than those from tap water systems or food, with the exception of colistin. Moreover, the drug resistance rate of strains isolated from tap water systems was significantly higher than that of clinical and food strains. Colistin is a last-resort antibacterial used to treat clinically serious infections caused by MDR gram-negative bacteria[38]. A new mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-3, has been detected in MDR bacteria isolated from severely ill patients in many countries. It is particularly important to determine the presence of these strains in meat products and drinking water due to their direct impact on public health[31]. In this study, three of the Aeromonas strains that were resistant to colistin harbored mcr-3 genes and were derived from the feces of patients with diarrhea, tap water, and fresh pork from the supermarket.

The existence of these mcr-3 genes is of great importance to global public health because obtaining an mcr-3 gene may lead to high levels of colistin resistance in Aeromonas, particularly since it is ubiquitous in soil and water systems and has the opportunity to interact with bacteria from a variety of different sources. Aeromonas species may therefore be a reservoir for mcr-3 and contribute toward its potential spread. In China, mcr genes have not only been detected in a large number of human pathogens, but also have a high positive test rate in animals (livestock, pets, and even wildlife) and the environment (soil and water)[39]. Since colistin is being used at increasingly high frequencies in veterinary and human medicine, it is essential to continuously monitor mcr genes in both clinical and environmental settings.

Resistance to SXT and quinolone, which are antimicrobials used to treat Aeromonas infection, has been widely documented. Deng et al.[40] reported that Aeromonas isolates collected from cultured freshwater animals have the 5% resistance for Ciprofloxacin and 18.86% resistance for SXT, at the same time, the detection rate of sul1 gene was 18.86% and that of qnrS gene was 4.7%. The researchers noted [33] that Aeromonas isolated from clinical patients have the 6.1% resistance rates of Ciprofloxacin, as well as 5.2% resistance rates of SXT. A total of 186 Aeromonas, collected from commercially reared fish and ornamental fish, were evaluated for their antimicrobial susceptibilities. The researchers[28] found that the resistance rate of SXT was 9.4%, and the detection rate of sul1 was 9.4%. In our study, the resistance rate of SXT was 16.7% and the detection rate of sul1 was 3.3%. As reported, the SXT resistance and its determinants are highly prevalent in Aeromonas[28,41,42], most likely due to the overuse of sulfonamide drugs in animal farms and fish ponds. PMQR genes have recently been characterized in Aeromonas strains[22,43]; Chenia[20] reported that qnrS was found to be present in 21% of Aeromonas isolates from freshwater fish in South Africa. In the present study, the detection rate of qnrS was 4.4%. however, when we screened the 90 Aeromonas isolates for the three PMQR genes qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS, only qnrS was detected in strains isolated from clinical specimens. It is thought that Aeromonas may act as a carrier of these resistance genes via horizontal transfer[44]; therefore, the prevalence of MDR in Aeromonas species could be considered a threat to public health.

-

We obtained 90 Aeromonas isolates from clinical patients, tap water systems, and food in Ma’anshan, Anhui Province, China. High genetic diversity was observed in these isolates, which belonged to 80 novel STs. Concatenated gyrB-cpn60 gene sequences classified 82 (91.1%) of the Aeromonas isolates into eight different species as well as several new species. Virulence genes were examined by PCR, indicating that the isolates may be pathogenic and pose a risk to human health. When measuring antibiotic resistance to ten distinct antibiotic classes, 21.1% of the strains were found to be MDR (≥ 3). The PMQR, ESBL, aminoglycoside resistance, sulphonamide, and mcr-3 genes were detected in the isolates, as well as a new mcr-3 gene variant. Thus, this study sheds light on the genetic diversity, antibiotic resistance, and pathogenicity of Aeromonas species identified from a variety of sources.

-

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

doi: 10.3967/bes2020.053

Genetic Diversity, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Virulence Genes of Aeromonas Isolates from Clinical Patients, Tap Water Systems, and Food

-

Abstract:

Objective This study aimed to evaluate the genetic diversity, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas isolates from clinical patients, tap water systems, and food. Methods Ninety Aeromonas isolates were obtained from Ma’anshan, Anhui province, China, and subjected to multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) with six housekeeping genes. Their taxonomy was investigated using concatenated gyrB-cpn60 sequences, while their resistance to 12 antibiotics was evaluated. Ten putative virulence factors and several resistance genes were identified by PCR and sequencing. Results The 90 Aeromonas isolates were divided into 84 sequence types, 80 of which were novel, indicating high genetic diversity. The Aeromonas isolates were classified into eight different species. PCR assays identified virulence genes in the isolates, with the enterotoxin and hemolysin genes act, aerA, alt, and ast found in 47 (52.2%), 13 (14.4%), 22 (24.4%), and 12 (13.3%) of the isolates, respectively. The majority of the isolates (≥ 90%) were susceptible to aztreonam, imipenem, cefepime, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin. However, several resistance genes were detected in the isolates, as well as a new mcr-3 variant. Conclusions Sequence type, virulence properties, and antibiotic resistance vary in Aeromonas isolates from clinical patients, tap water systems, and food. -

Key words:

- Aeromonas /

- Multi-locus sequence typing /

- Multidrug resistance /

- Virulence gene /

- Antimicrobial resistance gene

注释: -

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationships were determined using the concatenated sequences of six genes included in this study. The source, species, virulence genes, antibiotic resistance phenotype, MDR (number of drugs resistant to), and antimicrobial resistance genes of the Aeromonas isolates are shown on the right. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using a neighbor-joining algorithm. ST: sequence type.

Figure 2. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using the concatenated sequences of the gyrB and cpn60 genes, revealing the relationships between the 90 Aeromonas isolates from clinical patients, tap water systems, and food from Ma’anshan Anhui Province, China. Numbers on or near the nodes represent bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates. Isolates were designated as either P, E, or F to indicate strains isolated from clinical patients, tap water systems (environment), or food, respectively.

S1. The gyrB and cpn60 genes of twenty-eight representative Aeromonas species available in GenBank

Strains Species name GenBank locus gyrB cpn60 A.allosaccharophila-CECT4200 A. allosaccharophila AY101823 EU741624 A.bestiarum-112A A. bestiarum JN711733 EU741625 A.bestiarum-628A A. bestiarum JN711738 EU306797 A.bivalvium-665N A. bivalvium EF465524 EU306798 A.bivalvium-868E A. bivalvium EF465525 EU306799 A.caviae-CECT838 A. caviae JN829497 EU306800 A.encheleia-CECT4342 A. encheleia JN829499 EU306801 A.enteropelogenes-CECT4487 A. enteropelogenes EF465526 EU306837 A.eucrenophila-CECT4224 A. eucrenophila JN829501 EU306803 A.eucrenophila-CECT4854 A. eucrenophila AY101813 EU741634 A.hydrophila-CECT5236 A. hydrophila JN711791 EU741635 A.allosaccharophila-CECT4199 A. allosaccharophila JN829495 EU306795 A.aquariorum-MDC317 A. aquariorum HQ442717 JN711581 A.aquariorum-MDC573 A. aquariorum HQ442715 JN711582 A.aquariorum-MDC47 A. aquariorum EU268444 FJ936120 A.caviae-A4EL5 A. caviae JF938610 JF920575 A.caviae-E7EL42 A. caviae JF938613 JF920578 A.diversa-CECT4254 A. diversa JN829523 EU306835 A.diversa-CECT5178 A. diversa GU062401 GQ365713 A.encheleia-CECT4253 A. encheleia JN829522 EU306802 A.enteropelogenes-CECT4255 A. enteropelogenes JN829517 EU306836 A.fluvialis-717 A. fluvialis FJ603455 GU062398 A.hydrophila-AP60 A. hydrophila JF938654 JF920619 A.hydrophila-CECT839 A. hydrophila JN711776 EU306804 A.hydrophila-CF38 A. hydrophila JF938658 JF920623 A.jandaei-ATCC49568 A. jandaei FN706559 AY922357 A.jandaei-CECT4228 A. jandaei JN829507 EU306807 A.media-CECT4234 A. media KP400958 EU741641 A.media-CECT4232 A. media JN829508 EU306808 A.molluscorum-431E A. molluscorum EF465520 EU306810 A.molluscorum-848T A. molluscorum AM179827 EU306811 A.piscicola-R94 A. piscicola JN711768 JN711540 A.piscicola-S1.2 A. piscicola JN711765 GU062399 A.popoffii-LMG17541 A. popoffii JN711769 EU306814 A.salmonicida-CECT5173 A. salmonicida JN711837 EU741642 A.salmonicida-621A A. salmonicida JN711829 EU306819 A.salmonicida-856T A. salmonicida JN711833 EU306823 A.sanarellii-A2-67 A. sanarellii FJ807277 JN215527 A.sanarellii-E4P29 A. sanarellii JF938619 JF920584 A.sharmana-DSM17445 A. sharmana EF465528 EU306831 A.simiae-CIP107797 A. simiae AJ632225 EU306832 A.simiae-CIP107798 A. simiae JN829555 EU306833 A.sobria-CECT4245 A. sobria JN829516 EU306834 A.taiwanensis-A2-50 A. taiwanensis FJ807272 JN215528 A.veronii-AT46 A. veronii JF938687 JF920652 A.veronii-AT48 A. veronii JF938688 JF920653 A.veronii-CECT4257 A. veronii HQ442728 EU306838 A.veronii-CECT4486 A. veronii EF465527 EU306841 A.rivuli-CECT7518 A. rivuli CDBJ01000001 JN215526 A.schubertii-BT3-772 A. schubertii LC003078 LC003165 A.schubertii-BT3-777 A. schubertii LC003081 LC003168 A.tecta-CECT7082 A. tecta JN829521 NZ_CDCA01000043 A.cavernicola-MDC2508 A. cavernicola PGGC01000001 PGGC01000001 A.lusitana-MDC2473 A. lusitana PGCP01000001 PGCP01000001 Table 1. Primer sequences used to amplify antimicrobial resistance genes

Targeted gene Primers Sequence (5’→3’) Product size (bp) ESBL blaTEM blaTEM-F ATAAAATTCTTGAAGACGAAA 1,080 blaTEM-R GACAGTTACCAATGCTTAATC blaSHV blaSHV-F TTATCTCCCTGTTAGCCACC 795 blaSHV-R GATTTGCTGATTTCGCTCGG blaCTX-M blaCTX-M-F CGCTTTGCGATGTGCAG 550 blaCTX-M-R ACCGCGATATCGTTGGT Tetracycline resistance tetA tetA-F GTAATTCTGAGCACTGTCGC 1,000 tetA-R CTGCCTGGACAACATTGCTT tetB tetB-F CTCAGTATTCCAAGCCTTTG 400 tetB-R CTAAGCACTTGTCTCCTGTT tetE tetE-F GTGATGATGGCACTGGTCAT 1,100 tetE-R CTCTGCTGTACATCGCTCTT PMQR qnrA qnrA-F AGAGGATTTCTCACGCCAGG 580 qnrA-R TGCCAGGCACAGATCTTGAC qnrB qnrB-F GATCGTGAAAGCCAGAAAGG 496 qnrB-R ACGATGCCTGGTAGTTGTCC qnrS qnrS-F GCAAGTTCATTGAACAGGGT 428 qnrS-R TCTAAACCGTCGAGTTCGGCG Aminoglycoside resistance armA armA-F AGGTTGTTTCCATTTCTGAG 591 armA-R TCTCTTCCATTCCCTTCTCC aphAI-IAB aphAI-IAB-F AAACGTCTTGCTCGA GGC 500 aphAI-IAB-R CAAACCGTTATTCATTCGTGA aac(3)-IIa aac(3)-IIa-F ATGGGCATC ATTCGCACA 749 aac(3)-IIa-R TCTCGGCTTGAACGAATTGT aac(6’)-Ib aac(6’)-Ib-F TTGCGATGCTCTATGAGTGGCTA 482 aac(6’)-Ib-R CTCGAATGCCTGGCGTGTTT MCR mcr-1 mcr-1-F CGGTCAGTCCGTTTGTTC 309 mcr-2-R CTTGGTCGGTCTGTAGGG mcr-2 mcr-2-F TGTTGCTTGTGCCGATTGGA 567 mcr-2-R CAGCAACCAACAATACCATCT mcr-3 mcr-3-F AGTTTGGTTTCGCCATTTCATTAC 1,084 mcr-3-R ATATCACTGCGTGGACAGTCAGG mcr-4 mcr-4-F TTACAGCCAGAATCATTATCA 488 mcr-4-R ATTGGGATAGTCGCCTTTTT Sulfonamide resistance sul1 sul1-F CGGCGTGGGCTACCTGAACG 433 sul1-R GCCGATCGCGTGAAGTTCCG sul2 sul2-F GCGCTCAAGGCAGATGGCATT 293 sul2-R GCGTTTGATACCGGCACCCGT Table 2. Distribution of Aeromonas spp. in isolates collected from clinical patients, food, and tap water samples

Species Total strains (n, %) Clinical isolates (n, %) Environmental isolates (n, %) Food isolates (n, %) A. veronii 23 (25.5) 6 (18.1) 9 (25.0) 8 (38.1) A. caviae 12 (13.3) 12 (36.4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) A. aquariorum 7 (7.8) 4 (12.1) 2 (5.6) 1 (4.8) A. hydrophila 6 (6.7) 1 (3.0) 1 (2.8) 4 (19.0) A. jandaei 29 (32.2) 4 (12.1) 21 (58.3) 4 (19.0) A. enteropelogenes 2 (2.2) 1 (3.0) 1 (2.8) 0 (0.0) A. media 1 (1.1) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (4.8) A. salmonicida 2 (2.2) 0 (0.0) 1 (2.8) 1 (4.8) New species 8 (8.9) 5 (15.1) 1 (2.8) 2 (9.5) Total 90 33 36 21 Table 3. Distribution of virulence-associated genes in Aeromonas strains isolated clinical patients, food, and tap water samples

Gene Totalstrains (n, %) Clinical strains (n, %) Environmental strains (n, %) Food strains (n, %) act 47 (52.2) 15 (45.5) 18 (50.0) 14 (66.7) alt 22 (24.4) 11 (33.3) 4 (11.1) 7 (33.3) ast 12 (13.3) 1 (3.0) 3 (8.3) 8 (38.1) aerA 13 (14.4) 4 (12.1) 3 (8.3) 6 (28.6) hlyA 19 (21.1) 6 (18.2) 5 (13.9) 8 (33.3) ascV 39 (43.3) 12 (39.4) 19 (52.8) 8 (38.1) aexT 20 (22.2) 10 (30.3) 7 (19.4) 3 (14.3) fla 70 (77.8) 29 (87.9) 26 (72.2) 15 (71.4) lip 34 (37.7) 22 (69.7) 4 (11.1) 8 (38.1) ela 40 (44.4) 22 (66.7) 8 (22.2) 10 (47.6) laf 8 (8.9) 2 (6.1) 4 (11.1) 2 (9.5) Table 4. Distribution of virulence genes in the five most common Aeromonas spp.

Gene A. jandaei (n, %) A. veronii (n, %) A. caviae (n, %) A. aquariorum (n, %) A. hydrophila (n, %) act 8 (27.6) 21 (91.3) 2 (16.7) 3 (42.9) 5 (83.3) alt 0 (0.0) 1 (4.3) 2 (16.7) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) ast 0 (0.0) 2 (8.7) 0 (0.0) 2 (28.6) 6 (100.0) aerA 0 (0.0) 2 (8.7) 1 (8.3) 3 (42.9) 5 (83.3) hlyA 1 (3.4) 2 (8.7) 0 (0.0) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) ascV 18 (62.1) 12 (52.2) 2 (16.7) 2 (28.6) 1 (16.7) aexT 3 (10.3) 13 (56.5) 2 (16.7) 1 (14.3) 0 (0.0) fla 18 (62.1) 18 (78.3) 10 (83.3) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) lip 1 (3.4) 1 (4.3) 11 (91.7) 7 (100) 6 (100.0) ela 3 (10.3) 5 (100.0) 12 (100) 7 (100.0) 6 (100.0) laf 4 (13.8) 2 (8.7) 0 (0.0) 1 (14.3) 1 (16.7) Table 5. Prevalence of resistance to different antibiotics

Antibiotics Resistant isolates (n, %) Total strains (n, %) Clinical strains (n, %) Environmental strains (n, %) Food strains (n, %) Penicillins Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 78 (86.7) 31 (96.9) 29 (80.6) 18 (85.7) Ampicillin 90 (100.0) 33 (100.0) 36 (100.0) 21 (100.0) Caphems Cefepime 5 (5.6) 5 (15.6) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Ceftazidime 16 (17.8) 9 (28.1) 3 (8.3) 4 (19.0) Ceftriaxone 11 (12.2) 6 (18.8) 1 (2.8) 4 (19.0) Carbapenems Imipenem 3 (3.3) 1 (3.0) 2 (5.6) 0 (0.0) Monobactams Aztreonam 2 (2.2) 2 (6.1) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Aminoglycosides Gentamicin 3 (3.3) 3 (9.4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Tetracyclines Tetracycline 1 (1.1) 1 (3.1) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Quinolones Ciprofloxacin 5 (5.6) 5 (15.6) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Folate pathway inhibitors Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 15 (16.7) 8 (25.0) 2 (5.6) 5 (23.8) Phenicols Chloramphenicol 3 (3.3) 3 (9.4) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Polymyxins Colistin 38 (42.2) 10 (31.2) 21 (58.3) 7 (33.3) -

[1] Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2010; 23, 35−73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09 [2] Callister SM, Agger WA. Enumeration and characterization of Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas caviae isolated from grocery store produce. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1987; 53, 249−53. doi: 10.1128/AEM.53.2.249-253.1987 [3] Gobat PF, Jemmi T. Distribution of mesophilic Aeromonas species in raw and ready-to-eat fish and meat products in Switzerland. Int J Food Microbiol, 1993; 20, 117−20. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90099-3 [4] Tsai GJ, Chen TH. Incidence and toxigenicity of Aeromonas hydrophila in seafood. Int J Food Microbiol, 1996; 31, 121−31. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)00972-5 [5] Martinez-Murcia AJ, Monera A, Saavedra MJ, et al. Multilocus phylogenetic analysis of the genus Aeromonas. Syst Appl Microbiol, 2011; 34, 189−99. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.014 [6] Martinez-Murcia A, Beaz-Hidalgo R, Svec P, et al. Aeromonas cavernicola sp. nov., isolated from fresh water of a brook in a cavern. Curr Microbiol, 2013; 66, 197−204. doi: 10.1007/s00284-012-0253-x [7] Martinez-Murcia A, Beaz-Hidalgo R, Navarro A, et al. Aeromonas lusitana sp. nov., isolated from untreated water and vegetables. Curr Microbiol, 2016; 72, 795−803. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-0997-9 [8] Yanez MA, Catalan V, Apraiz D, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of members of the genus Aeromonas based on gyrB gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2003; 53, 875−83. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02443-0 [9] Soler L, Yanez MA, Chacon MR, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Aeromonas based on two housekeeping genes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2004; 54, 1511−9. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.03048-0 [10] Yano Y, Hamano K, Tsutsui I, et al. Occurrence, molecular characterization, and antimicrobial susceptibility of Aeromonas spp. in marine species of shrimps cultured at inland low salinity ponds. Food Microbiol, 2015; 47, 21−7. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.003 [11] Tomas JM. The main Aeromonas pathogenic factors. ISRN Microbiol, 2012; 256261. [12] Chopra AK, Houston CW, Peterson JW, et al. Cloning, expression, and sequence analysis of a cytolytic enterotoxin gene from Aeromonas hydrophila. Can J Microbiol, 1993; 39, 513−23. doi: 10.1139/m93-073 [13] Sha J, Kozlova EV, Chopra AK. Role of various enterotoxins in Aeromonas hydrophila-induced gastroenteritis: generation of enterotoxin gene-deficient mutants and evaluation of their enterotoxic activity. Infect Immun, 2002; 70, 1924−35. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1924-1935.2002 [14] Heuzenroeder MW, Wong CY, Flower RL. Distribution of two hemolytic toxin genes in clinical and environmental isolates of Aeromonas spp.: correlation with virulence in a suckling mouse model. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 1999; 174, 131−6. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13559.x [15] Rabaan AA, Gryllos I, Tomas JM, et al. Motility and the polar flagellum are required for Aeromonas caviae adherence to HEp-2 cells. Infect Immun, 2001; 69, 4257−67. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4257-4267.2001 [16] Gavin R, Merino S, Altarriba M, et al. Lateral flagella are required for increased cell adherence, invasion and biofilm formation by Aeromonas spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2003; 224, 77−83. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00418-X [17] Cascon A, Yugueros J, Temprano A, et al. A major secreted elastase is essential for pathogenicity of Aeromonas hydrophila. Infect Immun, 2000; 68, 3233−41. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3233-3241.2000 [18] Chuang YC, Chiou SF, Su JH, et al. Molecular analysis and expression of the extracellular lipase of Aeromonas hydrophila MCC-2. Microbiology, 1997; 143, 803−12. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-803 [19] Hossain S, De Silva BCJ, Wimalasena S, et al. Distribution of antimicrobial resistance genes and class 1 integron gene cassette arrays in motile Aeromonas spp. isolated from goldfish (Carassius auratus). Microb Drug Resist, 2018; 24, 1217−25. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0388 [20] Chenia HY. Prevalence and characterization of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes in Aeromonas spp. isolated from South African freshwater fish. Int J Food Microbiol, 2016; 231, 26−32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.04.030 [21] Arias A, Seral C, Navarro F, et al. Plasmid-mediated QnrS2 determinant in an Aeromonas caviae isolate recovered from a patient with diarrhoea. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2010; 16, 1005−7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02958.x [22] Cattoir V, Poirel L, Aubert C, et al. Unexpected occurrence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants in environmental Aeromonas spp. Emerg Infect Dis, 2008; 14, 231−7. doi: 10.3201/eid1402.070677 [23] Figueira V, Vaz-Moreira I, Silva M, et al. Diversity and antibiotic resistance of Aeromonas spp. in drinking and waste water treatment plants. Water Res, 2011; 45, 5599−611. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.08.021 [24] Minana-Galbis D, Urbizu-Serrano A, Farfan M, et al. Phylogenetic analysis and identification of Aeromonas species based on sequencing of the cpn60 universal target. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2009; 59, 1976−83. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.005413-0 [25] Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res, 1994; 22, 4673−80. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [26] Wimalasena S, De Silva BCJ, Hossain S, et al. Prevalence and characterisation of quinolone resistance genes in Aeromonas spp. isolated from pet turtles in South Korea. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2017; 11, 34−8. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.06.001 [27] Kerrn MB, Klemmensen T, Frimodt-Moller N, et al. Susceptibility of Danish Escherichia coli strains isolated from urinary tract infections and bacteraemia, and distribution of sul genes conferring sulphonamide resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2002; 50, 513−6. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf164 [28] Kadlec K, von Czapiewski E, Kaspar H, et al. Molecular basis of sulfonamide and trimethoprim resistance in fish-pathogenic Aeromonas isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2011; 77, 7147−50. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00560-11 [29] Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2016; 16, 161−8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 [30] Xavier BB, Lammens C, Ruhal R, et al. Identification of a novel plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance gene, mcr-2, in Escherichia coli, Belgium, June 2016. Euro Surveill, 2016; 21, 7. [31] Yin W, Li H, Shen Y, et al. Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. MBio, 2017; 8, e00543−17. [32] Carattoli A, Villa L, Feudi C, et al. Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mcr-4 gene in Salmonella and Escherichia coli, Italy 2013, Spain and Belgium, 2015 to 2016. Euro Surveill, 2017; 22, 30589. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.31.30589 [33] Zhou Y, Yu L, Nan Z, et al. Taxonomy, virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas isolated from extra-intestinal and intestinal infections. BMC Infect Dis, 2019; 19, 158−66. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3766-0 [34] Senderovich Y, Ken-Dror S, Vainblat I, et al. A molecular study on the prevalence and virulence potential of Aeromonas spp. recovered from patients suffering from diarrhea in Israel. PLoS One, 2012; 7, e30070-6. [35] Albert MJ, Ansaruzzaman M, Talukder KA, et al. Prevalence of enterotoxin genes in Aeromonas spp. isolated from children with diarrhea, healthy controls, and the environment. J Clin Microbiol, 2000; 38, 3785−90. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.10.3785-3790.2000 [36] Overman TL, Janda JM. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Aeromonas jandaei, A. schubertii, A. trota, and A. veronii biotype veronii. J Clin Microbiol, 1999; 37, 706−8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.3.706-708.1999 [37] Aravena-Roman M, Inglis TJ, Henderson B, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Aeromonas strains isolated from clinical and environmental sources to 26 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2012; 56, 1110−2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05387-11 [38] Mao J, Liu W, Wang W, et al. Antibiotic exposure elicits the emergence of colistin- and carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli coharboring MCR-1 and NDM-5 in a patient. Virulence, 2018; 9, 1001−7. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2018.1486140 [39] Xu Y, Zhong LL, Srinivas S, et al. Spread of MCR-3 colistin resistance in China: an epidemiological, genomic and mechanistic study. EBioMedicine, 2018; 34, 139−57. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.07.027 [40] Deng YT, Wu YL, Tan AP, et al. Analysis of antimicrobial resistance genes in Aeromonas spp. isolated from cultured freshwater animals in China. Microb Drug Resist, 2014; 20, 350−6. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0068 [41] Gao P, Mao D, Luo Y, et al. Occurrence of sulfonamide and tetracycline-resistant bacteria and resistance genes in aquaculture environment. Water Res, 2012; 46, 2355−64. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.02.004 [42] Hoa PT, Managaki S, Nakada N, et al. Antibiotic contamination and occurrence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in aquatic environments of northern Vietnam. Sci Total Environ, 2011; 409, 2894−901. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.04.030 [43] Han JE, Kim JH, Cheresca CH, et al. First description of the qnrS-like (qnrS5) gene and analysis of quinolone resistance-determining regions in motile Aeromonas spp. from diseased fish and water. Res Microbiol, 2012; 163, 73−9. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.09.001 [44] Carnelli A, Mauri F, Demarta A. Characterization of genetic determinants involved in antibiotic resistance in Aeromonas spp. and fecal coliforms isolated from different aquatic environments. Res Microbiol, 2017; 168, 461−71. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.02.006 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links