-

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a common progressive joint disease with chronic pain and movement disorders as the main clinical features. It is a major public health problem worldwide and it imposes serious medical and economic burdens. KOA accounts for nearly four-fifths of the global Osteoarthritis burden and increases with rising obesity and age[1]. There are many reasons for the change in disease prevalence and risk factors, such as urbanization, lifestyle changes, population aging, and sex imbalances. The prevalence of symptomatic KOA in middle aged and older individuals in China is 8.1%[2], and there is a rising trend. Patients with KOA require long-term treatment during the course of the disease and may receive a variety of drugs and non-drug interventions as a combined treatment[3]. Although Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) is usually the final choice, conservative treatment with or without drugs is usually the first-line intervention to avoid or delay surgery[4]. The use of nonsurgical therapies is often guided by differences in Chinese Medicine staging (CMS), based on the severity of the condition[5]. Therefore, it is necessary to study the characteristics and treatment status of KOA in urban residents in China. As an economic, cultural, political center, and first-tier city, Beijing has developed rapidly, and its urban, middle-aged, and elderly populations have exceeded the national average. Medical resources are more abundant, and diverse treatment methods can be utilized. Thus, the selection of the Beijing urban area as the survey object can better reflect the changes in urbanization on KOA. Currently, there are no large-scale epidemiological investigations or treatment status analyses of urban residents in China.

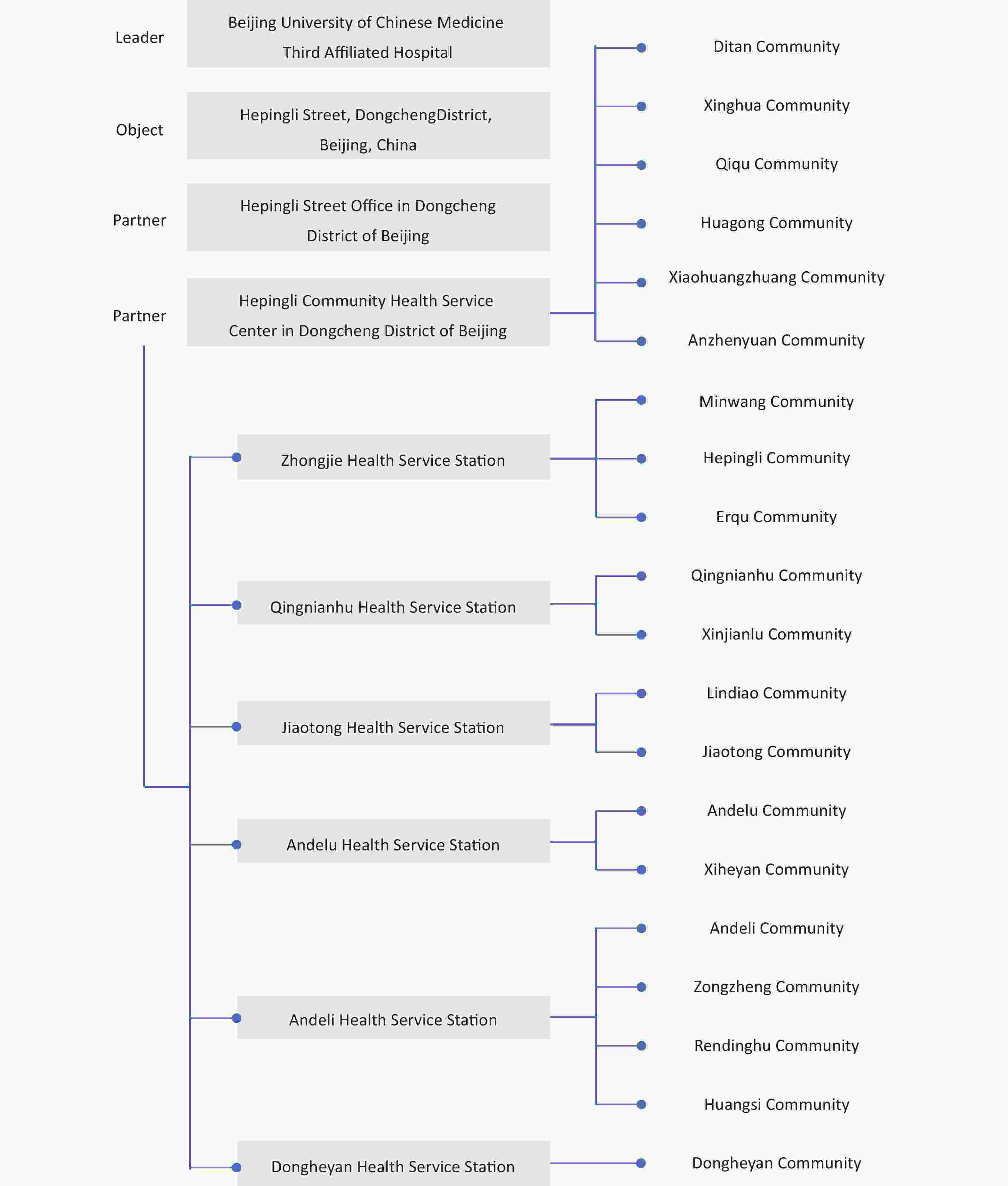

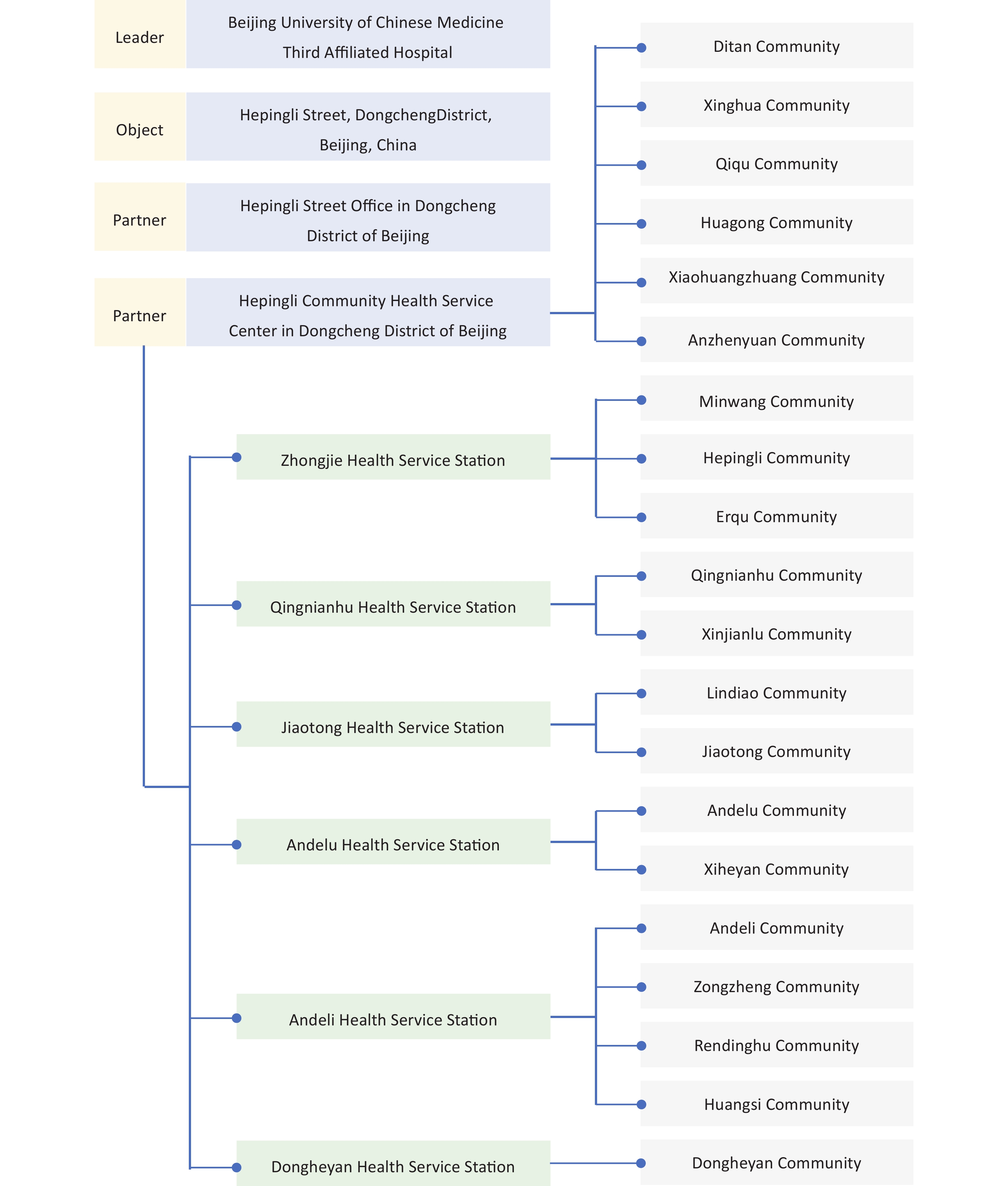

This study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Third Affiliated Hospital, approval number: BZYSY-2022KYKTPJ-04, and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, registration number: ChiCTR2200062700. The study was led by the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Third Affiliated Hospital. All streets in the Beijing urban area were selected from, using random cluster sampling. All residents (permanent residents, residents with formal household registration, or residence permits) of Hepingli Street in the Dongcheng District of Beijing were selected as the research objects. The study was conducted in cooperation with the Hepingli Street Office in the Dongcheng District of Beijing and the Hepingli Community Health Service Center in the Dongcheng District of Beijing. There are 20 communities on Hepingli Street, and the specific investigation work and community situation are shown in Supplementary Figure S1 (available in www.besjournal.com).

The survey covered the period from January 1, 2022, to June 30, 2022. The investigators of the Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Third Affiliated Hospital, medical workers of the community health service center or community health service station, and social workers of the Hepingli Subdistrict Office participated in the investigation. Investigators were responsible for recording information through outpatient, telephone, and visitation surveys, which includes general information, past history, and personal history. Among them, three floors or above three floors were considered high floors. For patients who were diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis, clinical data, such as the visual analogue scale (VAS) and Kellgren-Lawrence grading (KLG) were recorded. Treatment status referred to the recommended items of the knee osteoarthritis diagnosis and treatment guidelines, including basic treatment, western medicine treatment, traditional Chinese medicine treatment, physical treatment, and surgical treatment. The diagnosis of KOA is based on the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) diagnostic criteria[6], mainly based on the patient’s clinical symptoms and signs, combined with imaging examinations for diagnosis. Knee osteoarthritis CMS was categorized into three stages[5]: 1) CMS I: mild pain, mainly including soreness, accompanied by lassitude, and inability to walk for a long time. 2) CMS II: moderate pain, mainly including vague pain, accompanied by soreness and weakness of the waist and knee, and aggravated by physical activity. 3) CMS III: severe pain, mainly including stabbing, distending, and scorching pain, accompanied by joint heaviness, aggravation with cold and alleviation with warmth.

The survey results show that there were 139,032 people in Hepingli Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing, with 71,239 males and 67,793 females. A total of 38,850 residents (aged ≥ 40) were included, including 16,536 males and 22,314 females aged 40–106. The total prevalence of KOA in urban residents of Beijing, China, is 8.0%, lower than the the global prevalence (16.0%)[7], with 6.36% in males and 9.72% in females. The prevalence in people over 40 years old is 28.63%, which is higher than the global prevalence of people over 40 years old (22.9%)[7], with 24.44 % (4,531) in males and 32.45% (6,591) in females. A chi-square test was conducted on the factors related to KOA, which showed that there were significant differences between KOA and non-KOA patients in terms of sex, age, BMI, living environment, knee joint trauma history, KOA family history, osteoporosis history, drinking history, education, and occupation (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in smoking history (P > 0.05). Table 1 presents the results of the study.

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents by status of KOA and non-KOA groups

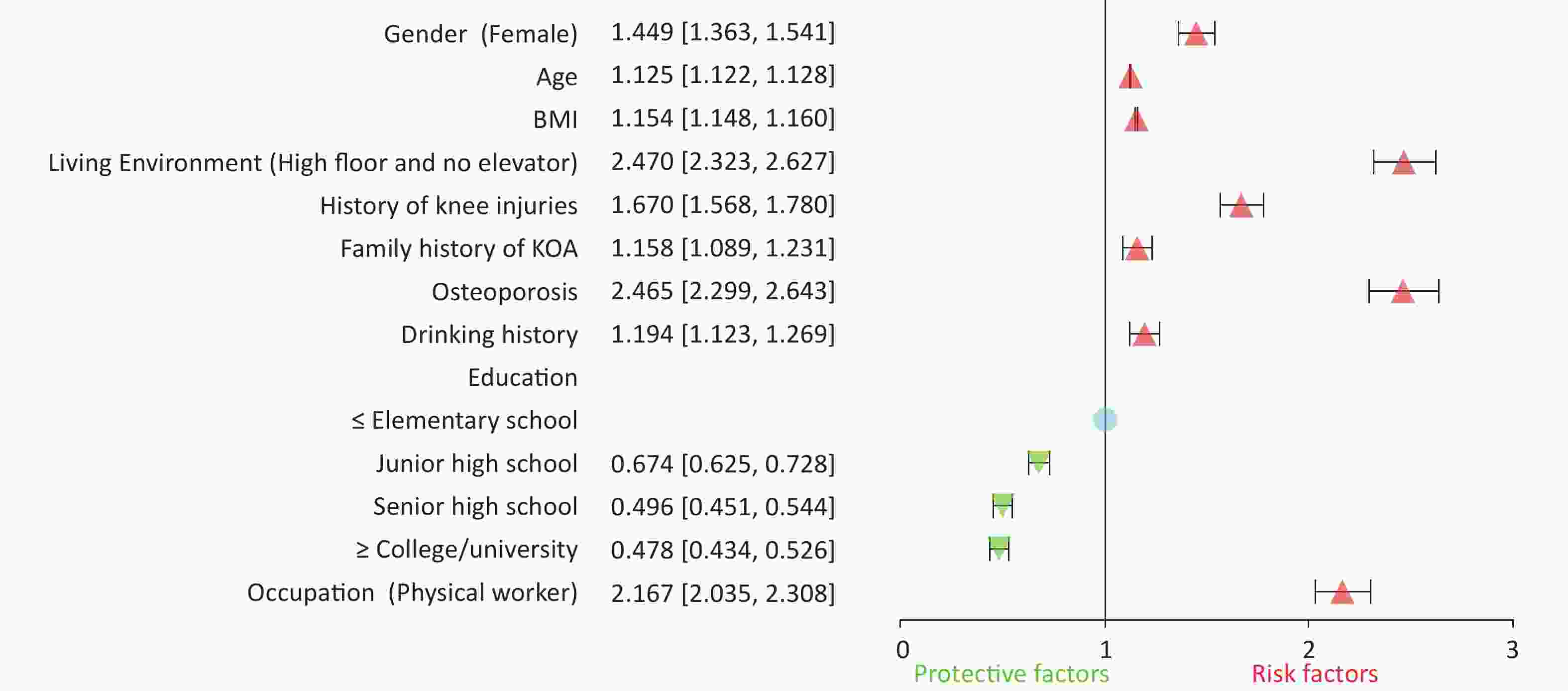

Variables Residents (aged ≥ 40) KOA Non-KOA P n = 38,850 Percent (%) n = 11,122 Percent (%) n = 27,728 Percent (%) Gender Male 18,536 47.71 4,531 40.74 14005 50.51 < 0.001 Female 20,314 52.29 6,591 59.26 13723 49.49 Age, years 40–49 18,127 46.66 754 6.77 17,373 62.66 < 0.001 50–59 7,716 19.86 1,218 10.95 6,498 23.43 60–69 4,630 11.92 2,828 25.43 1,802 6.50 70–79 4,297 11.06 3,017 27.13 1,280 4.62 ≥ 80 4,080 10.50 3,305 29.72 775 2.79 BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 3,243 8.35 827 7.43 2,416 8.71 < 0.001 18.5–23.9 19,948 51.35 4,216 37.91 15,732 56.74 24.0–27.9 12,899 33.20 4,562 41.02 8,337 30.07 > 28.0 2,760 7.10 1,517 13.64 1,243 4.48 Living Environment High floor and no elevator 17,169 44.19 6,685 60.11 10,484 37.81 < 0.001 Lower floor or elevator 21,681 55.81 4,437 39.89 17,244 62.19 History of knee injuries Yes 13,001 33.46 4,675 42.03 8,326 30.03 < 0.001 No 25,849 66.54 6,447 57.97 19,402 69.97 Family history of KOA Yes 16,536 42.56 5,015 45.09 11,521 41.55 < 0.001 No 22,314 57.44 6,107 54.91 16,207 58.45 Osteoporosis Yes 8,414 21.66 3,823 34.37 4,591 16.56 < 0.001 No 30,436 78.34 7,299 65.63 23,137 83.44 Smoking history Yes 23,981 61.73 6,925 62.26 17,056 61.51 0.168 No 14,869 38.27 4,197 37.74 10,672 38.49 Drinking history Yes 20,555 52.91 6,228 56.00 14,327 51.67 < 0.001 No 18,295 47.09 4,894 44.00 13,401 48.33 Education ≤ Elementary school 9,357 24.08 3,541 31.84 5,816 20.98 < 0.001 Junior high school 14,775 38.03 4,261 38.31 10,514 37.91 Senior high school 7,581 19.51 1,728 15.54 5,853 21.11 ≥ College/university 7,137 18.37 1,592 14.31 5,545 20.00 Occupation Physical worker 21,208 54.59 7,516 67.58 13,692 49.38 < 0.001 Non-physical worker 17,642 45.41 3,606 32.42 14,036 50.62 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthriis; BMI, Body Mass Index. Logistic regression analysis was conducted on the factors associated with KOA that showed a statistically significant difference. The results showed that the prevalence of KOA was significantly correlated with sex, age, BMI, living environment, knee joint trauma history, family history of KOA, osteoporosis history, drinking history, and occupation (P < 0.001), which were risk factors for KOA (odds ratio [OR] > 1). There was a significant correlation between the prevalence of KOA and education (P < 0.001), which was a protective factor against KOA (OR < 1). The results are shown in Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1 (available in www.besjournal.com).

Among the KOA patients, 991 (8.91 %) were in CMS III, aged 40–102 years, 3,738 (33.61%) were in CMS II, aged 40–103 years, and 6,393 (57.48 %) were in CMS I, aged 40–100 years. There were statistical differences in sex, age, BMI, and KLG in different stages. The results showed that CMS III was the highest, CMS II was the second highest, and CMS I was the lowest in terms of the proportion of female, average age, proportion of older individuals, BMI, and KLG, which were statistically significant (P < 0.001). The results are shown in Supplementary Table S2 (available in www.besjournal.com).

Table S2. General survey results of different stages of KOA

Variables CMS III CMS II CMS I P n = 991 Percent (%) n = 3,738 Percent (%) n = 6,393 Percent (%) Gender Male 293 29.57 1,392 37.24 2,846 44.52 < 0.001 Female 698 70.43 2,346 62.76 3,547 55.48 Age, years (mean ± SE) 74.51 ± 18.51 73.64 ± 19,70 67.16 ± 20.46 < 0.001 40–49 42 4.24 274 7.33 438 6.85 < 0.001 50–59 194 19.58 346 9.26 678 10.61 60–69 254 25.63 645 17.26 1,929 30.17 70–79 314 31.68 975 26.08 1,728 27.03 ≥ 80 187 18.87 1,498 40.07 1,620 25.34 BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SE) 25.51 ± 5.15 24.61 ± 6.25 23.84 ± 5.82 < 0.001 < 18.5 86 8.68 101 2.70 640 10.01 < 0.001 18.5–23.9 159 16.04 984 26.33 3,073 48.07 24–27 411 41.47 1,989 53.21 2,162 33.82 > 28 335 33.10 664 17.76 518 8.10 VAS 8.23 ± 1.35 5.75 ± 1.42 2.42 ± 1.56 < 0.001 K-L scale 991 3,487 5,827 0 0 0.00 28 0.75 146 2.28 < 0.001 1 33 3.33 216 5.78 1,327 20.76 2 152 15.34 1,759 47.06 3,516 55.00 3 456 46.01 1,216 32.53 213 3.33 4 350 35.32 268 7.17 625 9.78 None x-ray 0 251 566 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthritis; CMS, Chinese Medicine staging; BMI, Body Mass Index. Patients with KOA mainly use Chinese patent medicines for external use, with health education being the most common. Among them, the treatment methods of CMS III (the top five methods of frequency) were external use of Chinese patent medicine 67.10%, oral use of Chinese patent medicine 52.07%, health education 46.52%, weight management 32.80%, and external use of Chinese herbal medicine 29.47%. The main treatment methods of CMS II (the top five methods of frequency) are Chinese patent medicine for external use (70.33%), health education (54.87%), cupping (40.56%), physical therapy (39.35%), and exercise (33.63%). The main treatment methods of CMS I (the top five methods of frequency) are health education 66.87%, Chinese patent medicine 49.19%, traditional exercises 38.60%, exercise 31.53%, and cupping 20.77%. Details are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis in different stages

Treatment CMS III CMS II CMS I n = 991 Percent (%) n = 3,738 Percent (%) n = 6,393 Percent (%) Health Education 461 46.52 2,051 54.87 4,275 66.87 Weight Management 325 32.80 1,004 26.86 1,051 16.44 Exercise 62 6.26 1,257 33.63 2,016 31.53 Oral Western Medicine 150 15.14 279 7.46 210 3.28 Western Medicine for External Use 216 21.80 415 11.10 245 3.83 Intra-Articular Injection 121 12.21 251 6.71 451 7.05 Physical Therapy 178 17.96 1,471 39.35 1,204 18.83 Surgery 93 9.38 225 6.02 272 4.25 Traditional Exercises 71 7.16 451 12.07 2,468 38.60 Oral Chinese Herbal Medicine 213 21.49 278 7.44 256 4.00 Oral Chinese Patent Medicine 516 52.07 852 22.79 517 8.09 Chinese Herbal Medicine for External Use 292 29.47 482 12.89 225 3.52 Chinese Patent Medicine for External Use 665 67.10 2,629 70.33 3,145 49.19 Acupuncture 234 23.61 1,061 28.38 828 12.95 Moxibustion 55 5.55 513 13.72 426 6.66 Needle Knife 78 7.87 462 12.36 328 5.13 Cupping 162 16.35 1,516 40.56 1,328 20.77 Pricking Cupping 78 7.87 273 7.30 241 3.77 Manipulation 43 4.34 326 8.72 432 6.76 Note. CMS, Chinese Medicine staging. Unlike other countries, Chinese patent medicine is widely used throughout the course of the disease, and its clinical efficacy has been recognized by international scholars. In addition, Chinese herbal medicine, acupuncture, and cupping also play a significant role in controlling symptoms. In terms of improving muscle function around the knee joint, the curative effect of traditional exercises, such as Tai Chi and Baduanjin, are superior to quadriceps femoris exercise, which can significantly improve knee joint pain, body function, and quality of life[8]. International guidelines also provide a clear explanation for the application of traditional medicines in KOA, including traditional Chinese medicine[9]. In recent years, the importance of health education has been emphasized. Studies have shown that self-management may help to improve pain, knee function, stiffness, swelling, mental health, and quality of life in KOA patients[10]. The course of KOA is as long as decades. Through imaging examinations, it can be intuitively observed that the knee joint constantly deteriorates and is aggravated. However, the reason for the patient’s visit is usually pain. Pain relief during treatment is important. However, for patients with high KLG, the effect of drug treatment is poor; therefore, clinical symptoms and imaging grading should be comprehensively considered.

Depending on the severity of pain, patients with CMS III choose 4–5 treatment methods simultaneously, and patients with CMS II and CMS I choose 2–3 treatment methods simultaneously. There were significant differences in the choice of treatment between the different stages (P < 0.001). The results are shown in Supplementary Table S3 (available in www.besjournal.com). The combined application of multiple treatment methods can better alleviate clinical symptoms, and the more severe clinical symptoms are selected.

Table S3. KOA in different stages of treatment options

Number of treatments CMS III CMS II CMS I P n = 991 Percent (%) n = 3,738 Percent (%) n = 6,393 Percent (%) 1 72 7.27 464 12.41 1374 21.49 < 0.001 2–3 425 42.89 1959 52.41 4162 65.1 4–5 448 45.21 1170 31.3 857 13.41 > 5 46 4.63 145 3.88 0 0 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthritis; CMS, Chinese Medicine staging. Our study had some limitations. First, although the survey population was nearly 140,000, we conducted a census on only one street. The regional economy and medical resources are superior, but there are many old urban areas, which may have biased environmental impact factors. Second, based on the sixth census and the health records of community health service centers and stations, permanent residents were investigated. The floating population was not considered in this study. Considering that the floating population consisted mainly of young and middle-aged individuals, there may have been some additional bias towards the effects of age.

In summary, the prevalence of KOA in urban residents in Beijing, China was 8.0%, which is lower than the global level. The prevalence was related to female sex, advanced age, obesity, living environment, and occupation. Old age and obesity are important factors that affect KOA progression. Patented Chinese medicines are widely used for drug treatment and traditional exercises are more widely used in exercise rehabilitation.

-

Table S1. Logistic regression analysis of KOA related factors

Related factors Uncorrected Corrected OR 95% CI OR 95% CI Gender (Female vs. Male) 1.485 1.420–1.552 1.449 1.363–1.541 Age, years 1.126 1.123–1.128 1.125 1.122–1.128 BMI (kg/m2) 1.158 1.151–1.165 1.154 1.148–1.160 Living Environment (High floor and no elevator vs. Lower floor or elevator) 2.478 2.369–2.592 2.470 2.323–2.627 History of knee injuries (Yes vs. No) 1.690 1.615–1.769 1.670 1.568–1.780 Family history of KOA (Yes vs. No) 1.155 1.104–1.207 1.158 1.089–1.231 Osteoporosis (Yes vs. No) 2.536 2.411–2.667 2.465 2.299–2.643 Smoking history (Yes vs. No) 1.032 0.987–1.080 1.060 0.995–1.129 Drinking history (Yes vs. No) 1.190 1.139–1.244 1.194 1.123–1.269 Education ≤ Elementary school Junior high school 0.666 0.630–0.703 0.674 0.625–0.728 Senior high school 0.485 0.453–0.519 0.496 0.451–0.544 ≥ College/university 0.472 0.440–0.506 0.478 0.434–0.526 Occupation (Physical worker vs. Non–physical worker) 2.137 2.040–2.238 2.167 2.035–2.308 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthritis; BMI, Body Mass Index.

doi: 10.3967/bes2024.045

Prevalence, Characteristics and Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis in Urban Residents of Beijing, China: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study

-

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释: -

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents by status of KOA and non-KOA groups

Variables Residents (aged ≥ 40) KOA Non-KOA P n = 38,850 Percent (%) n = 11,122 Percent (%) n = 27,728 Percent (%) Gender Male 18,536 47.71 4,531 40.74 14005 50.51 < 0.001 Female 20,314 52.29 6,591 59.26 13723 49.49 Age, years 40–49 18,127 46.66 754 6.77 17,373 62.66 < 0.001 50–59 7,716 19.86 1,218 10.95 6,498 23.43 60–69 4,630 11.92 2,828 25.43 1,802 6.50 70–79 4,297 11.06 3,017 27.13 1,280 4.62 ≥ 80 4,080 10.50 3,305 29.72 775 2.79 BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 3,243 8.35 827 7.43 2,416 8.71 < 0.001 18.5–23.9 19,948 51.35 4,216 37.91 15,732 56.74 24.0–27.9 12,899 33.20 4,562 41.02 8,337 30.07 > 28.0 2,760 7.10 1,517 13.64 1,243 4.48 Living Environment High floor and no elevator 17,169 44.19 6,685 60.11 10,484 37.81 < 0.001 Lower floor or elevator 21,681 55.81 4,437 39.89 17,244 62.19 History of knee injuries Yes 13,001 33.46 4,675 42.03 8,326 30.03 < 0.001 No 25,849 66.54 6,447 57.97 19,402 69.97 Family history of KOA Yes 16,536 42.56 5,015 45.09 11,521 41.55 < 0.001 No 22,314 57.44 6,107 54.91 16,207 58.45 Osteoporosis Yes 8,414 21.66 3,823 34.37 4,591 16.56 < 0.001 No 30,436 78.34 7,299 65.63 23,137 83.44 Smoking history Yes 23,981 61.73 6,925 62.26 17,056 61.51 0.168 No 14,869 38.27 4,197 37.74 10,672 38.49 Drinking history Yes 20,555 52.91 6,228 56.00 14,327 51.67 < 0.001 No 18,295 47.09 4,894 44.00 13,401 48.33 Education ≤ Elementary school 9,357 24.08 3,541 31.84 5,816 20.98 < 0.001 Junior high school 14,775 38.03 4,261 38.31 10,514 37.91 Senior high school 7,581 19.51 1,728 15.54 5,853 21.11 ≥ College/university 7,137 18.37 1,592 14.31 5,545 20.00 Occupation Physical worker 21,208 54.59 7,516 67.58 13,692 49.38 < 0.001 Non-physical worker 17,642 45.41 3,606 32.42 14,036 50.62 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthriis; BMI, Body Mass Index. S2. General survey results of different stages of KOA

Variables CMS III CMS II CMS I P n = 991 Percent (%) n = 3,738 Percent (%) n = 6,393 Percent (%) Gender Male 293 29.57 1,392 37.24 2,846 44.52 < 0.001 Female 698 70.43 2,346 62.76 3,547 55.48 Age, years (mean ± SE) 74.51 ± 18.51 73.64 ± 19,70 67.16 ± 20.46 < 0.001 40–49 42 4.24 274 7.33 438 6.85 < 0.001 50–59 194 19.58 346 9.26 678 10.61 60–69 254 25.63 645 17.26 1,929 30.17 70–79 314 31.68 975 26.08 1,728 27.03 ≥ 80 187 18.87 1,498 40.07 1,620 25.34 BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SE) 25.51 ± 5.15 24.61 ± 6.25 23.84 ± 5.82 < 0.001 < 18.5 86 8.68 101 2.70 640 10.01 < 0.001 18.5–23.9 159 16.04 984 26.33 3,073 48.07 24–27 411 41.47 1,989 53.21 2,162 33.82 > 28 335 33.10 664 17.76 518 8.10 VAS 8.23 ± 1.35 5.75 ± 1.42 2.42 ± 1.56 < 0.001 K-L scale 991 3,487 5,827 0 0 0.00 28 0.75 146 2.28 < 0.001 1 33 3.33 216 5.78 1,327 20.76 2 152 15.34 1,759 47.06 3,516 55.00 3 456 46.01 1,216 32.53 213 3.33 4 350 35.32 268 7.17 625 9.78 None x-ray 0 251 566 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthritis; CMS, Chinese Medicine staging; BMI, Body Mass Index. Table 2. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis in different stages

Treatment CMS III CMS II CMS I n = 991 Percent (%) n = 3,738 Percent (%) n = 6,393 Percent (%) Health Education 461 46.52 2,051 54.87 4,275 66.87 Weight Management 325 32.80 1,004 26.86 1,051 16.44 Exercise 62 6.26 1,257 33.63 2,016 31.53 Oral Western Medicine 150 15.14 279 7.46 210 3.28 Western Medicine for External Use 216 21.80 415 11.10 245 3.83 Intra-Articular Injection 121 12.21 251 6.71 451 7.05 Physical Therapy 178 17.96 1,471 39.35 1,204 18.83 Surgery 93 9.38 225 6.02 272 4.25 Traditional Exercises 71 7.16 451 12.07 2,468 38.60 Oral Chinese Herbal Medicine 213 21.49 278 7.44 256 4.00 Oral Chinese Patent Medicine 516 52.07 852 22.79 517 8.09 Chinese Herbal Medicine for External Use 292 29.47 482 12.89 225 3.52 Chinese Patent Medicine for External Use 665 67.10 2,629 70.33 3,145 49.19 Acupuncture 234 23.61 1,061 28.38 828 12.95 Moxibustion 55 5.55 513 13.72 426 6.66 Needle Knife 78 7.87 462 12.36 328 5.13 Cupping 162 16.35 1,516 40.56 1,328 20.77 Pricking Cupping 78 7.87 273 7.30 241 3.77 Manipulation 43 4.34 326 8.72 432 6.76 Note. CMS, Chinese Medicine staging. S3. KOA in different stages of treatment options

Number of treatments CMS III CMS II CMS I P n = 991 Percent (%) n = 3,738 Percent (%) n = 6,393 Percent (%) 1 72 7.27 464 12.41 1374 21.49 < 0.001 2–3 425 42.89 1959 52.41 4162 65.1 4–5 448 45.21 1170 31.3 857 13.41 > 5 46 4.63 145 3.88 0 0 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthritis; CMS, Chinese Medicine staging. S1. Logistic regression analysis of KOA related factors

Related factors Uncorrected Corrected OR 95% CI OR 95% CI Gender (Female vs. Male) 1.485 1.420–1.552 1.449 1.363–1.541 Age, years 1.126 1.123–1.128 1.125 1.122–1.128 BMI (kg/m2) 1.158 1.151–1.165 1.154 1.148–1.160 Living Environment (High floor and no elevator vs. Lower floor or elevator) 2.478 2.369–2.592 2.470 2.323–2.627 History of knee injuries (Yes vs. No) 1.690 1.615–1.769 1.670 1.568–1.780 Family history of KOA (Yes vs. No) 1.155 1.104–1.207 1.158 1.089–1.231 Osteoporosis (Yes vs. No) 2.536 2.411–2.667 2.465 2.299–2.643 Smoking history (Yes vs. No) 1.032 0.987–1.080 1.060 0.995–1.129 Drinking history (Yes vs. No) 1.190 1.139–1.244 1.194 1.123–1.269 Education ≤ Elementary school Junior high school 0.666 0.630–0.703 0.674 0.625–0.728 Senior high school 0.485 0.453–0.519 0.496 0.451–0.544 ≥ College/university 0.472 0.440–0.506 0.478 0.434–0.526 Occupation (Physical worker vs. Non–physical worker) 2.137 2.040–2.238 2.167 2.035–2.308 Note. KOA, Knee osteoarthritis; BMI, Body Mass Index. -

[1] Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Smith E, et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis, 2020; 79, 819−28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515 [2] Tang X, Wang SF, Zhan SY, et al. The prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in China: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2016; 68, 648−53. doi: 10.1002/art.39465 [3] Geng R, Li J, Yu C, et al. Knee osteoarthritis: Current status and research progress in treatment (Review). Exp Ther Med, 2023; 26, 481. [4] Lim WB, Al-Dadah O. Conservative treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a review of the literature. World J Orthop, 2022; 13, 212−29. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v13.i3.212 [5] Chen W, Ding C, Wang C, et al. Better management of knee osteoarthritis: Chinese medicine treatment guideline. Osteoarthr Cartil, 2023; 31 Suppl 1, S168-9. [6] Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2020; 72, 220-33. [7] Cui AY, Li HZ, Wang DW, et al. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine, 2020; 29-30, 100587. [8] Li RY, Sun PP, Zhan Y, et al. Efficacy of leg swing versus quadriceps strengthening exercise among patients with knee osteoarthritis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 2022; 23, 323. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06282-0 [9] Brophy RH, Fillingham YA. AAOS clinical practice guideline summary: management of osteoarthritis of the knee (Nonarthroplasty), Third Edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2022; 30, e721−9. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-01233 [10] Wu ZG, Zhou R, Zhu Y, et al. Self-management for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag, 2022; 2022, 2681240. -

23305+Supplementary Materials.pdf

23305+Supplementary Materials.pdf

-

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links