-

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is often accompanied by chronic kidney disease (CKD) and metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes[1]. The coexistence of these conditions can lead to systemic dysfunction and substantially increase adverse cardiovascular outcomes. To describe this interplay, the American Heart Association (AHA) recently proposed the concept of cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome[1]. However, its risk-enhancing factors and underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The menopausal transition is a critical period marked by adverse cardiometabolic changes[2], and premature menopause has been associated with higher risks of metabolic disease[3], CKD[4], and CVD[5]. Nevertheless, its role in CKM syndrome has not been established.

Aging is a key determinant of CVD. Biomarker-based biological age (BA), estimated through approaches such as the Klemera–Doubal method (KDM) and PhenoAge, reflects individual aging more accurately than does chronological age and may be influenced by age at menopause[6]. Therefore, we hypothesized that premature menopause increases CKM risk through accelerated BA. Moreover, social determinants of health (SDOH) may interact with biological factors to exacerbate CKM outcomes. The polysocial risk score (PsRS), an indicator of cumulative exposure to adverse social factors[7], provides a means to assess comprehensively individual-level social risk.

The present study was performed to examine the association between premature menopause and incident CKM syndrome, evaluate the mediating role of BA, and explore the interactive effect of premature menopause and the PsRS among postmenopausal women.

The UK Biobank is a population-based cohort study that enrolled more than 500,000 participants between 2006 and 2010. Among 154,592 postmenopausal women, we excluded those without data on CKM syndrome diagnosis (n = 22,300) or PsRS calculation (n = 45,294). In total, 86,904 participants free of CKM syndrome at baseline were included in the final analyses. Baseline information, physical measurements, and biological samples were collected at recruitment.

Data on age at menopause were obtained through self-report, based on the question, “How old were you when your periods stopped?” Natural menopause was defined as menopause not caused by surgery. Participants were also asked, “How old were you when you had a hysterectomy or both ovaries removed?” Those who underwent hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy before the onset of menopause were classified as having surgical menopause. Premature menopause was defined as menopause occurring before 40 years of age, consistent with cardiovascular society guidelines.

Based on the AHA definition, CKM syndrome was staged according to metabolic syndrome, CKD, and CVD status. Stages 3 and 4, characterized by subclinical or clinical CVD, were defined as high-risk phenotypes requiring intensified intervention. In the UK Biobank, CKM cases included participants with advanced CKD, excess or dysfunctional adiposity, and CVD. Detailed definitions, data fields, and International Classification of Diseases codes are provided in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4. Follow-up time was calculated from recruitment to the first occurrence of CKM syndrome, loss to follow-up (n = 170), death (n = 4,800), or the end of follow-up, whichever occurred first.

We estimated BA using two validated algorithms, KDM and PhenoAge. KDM-BA was derived from regressions of lung function, systolic blood pressure, and seven blood biomarkers on chronological age, while PhenoAge was constructed based on mortality hazards of nine blood biomarkers. The 14 biological traits used to calculate BA and their corresponding data fields in the UK Biobank are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Age acceleration (AA) was defined as the residual of BA regressed on chronological age, with values above zero indicating an older phenotype. In addition, we constructed a PsRS based on 16 SDOH across three domains: socioeconomic status, psychosocial factors, and neighborhood and living environment. Detailed descriptions and population distributions of the social risk factors are presented in Supplementary Table S2. Each SDOH was coded as 0 (low risk) or 1 (high risk). After Bonferroni correction (P < 0.0031), only SDOH significantly associated with CKM syndrome were retained, and their scores were summed to generate the PsRS.

We employed Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between premature menopause, AAs, and PsRS with incident CKM syndrome. The proportional hazards assumption was tested and met for all Cox models. Multivariable models were adjusted for age at recruitment, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, healthy alcohol intake, healthy physical activity, healthy diet, and further for education and employment status.

Age at menopause and AAs were standardized to per standard deviation (SD) units. To examine dose–response relationships, we first tested linear trends by modeling age at menopause, AAs, and PsRS as continuous variables. Potential nonlinear associations were further assessed using restricted cubic spline regression with three knots placed at conventional percentiles of the exposure distributions. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated to compare the cumulative incidence of CKM syndrome between women with and without premature menopause, and differences were formally tested using log-rank tests. Mediation analysis was conducted to assess the role of AAs, with age at menopause inverted to ensure consistent directionality. Effect modification by PsRS was examined using restricted cubic spline regression models, with multiplicative interaction evaluated via likelihood-ratio tests and additive interaction quantified by relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), synergy index (SI), and attributable proportion (AP). To assess the robustness of our findings, we performed Fine–Gray subdistribution hazard models with mortality and loss to follow-up as competing events, and we conducted sensitivity analyses of CKM stages using ordinal regression models.

Age among the 86,904 eligible postmenopausal women ranged from 40 to 71 years. A total of 3,470 (4.0%) participants reported premature menopause, including 1,588 (1.83%) natural and 1,882 (2.17%) surgical cases. During a median follow-up of 11.14 years, 1,687 (1.94%) incident CKM syndrome cases were recorded. Among the 16 preselected SDOH indicators, 13 were significantly associated with elevated CKM risk after Bonferroni correction (Supplementary Table S5). Based on these factors, participants were grouped into low (≤ 3), intermediate (4–6), and high (≥ 7) PsRS categories. Baseline characteristics of the study population by CKM syndrome status are presented in Table 1. Compared to women without CKM syndrome, those who developed CKM syndrome were older, had a higher BMI, engaged less in healthy lifestyle behaviors, and were more likely to report premature menopause (7.7% vs. 3.9%, P < 0.001). They also had higher KDM-BA (−3.90 ± 3.67 vs. −5.58 ± 3.25 years, P < 0.001) and PhenoAge accelerations (−6.84 ± 6.90 vs. −11.85 ± 5.23 years, P < 0.001), as well as a higher prevalence of high polysocial risk (73.5% vs. 54.9%, P < 0.001).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants according to CKM syndrome

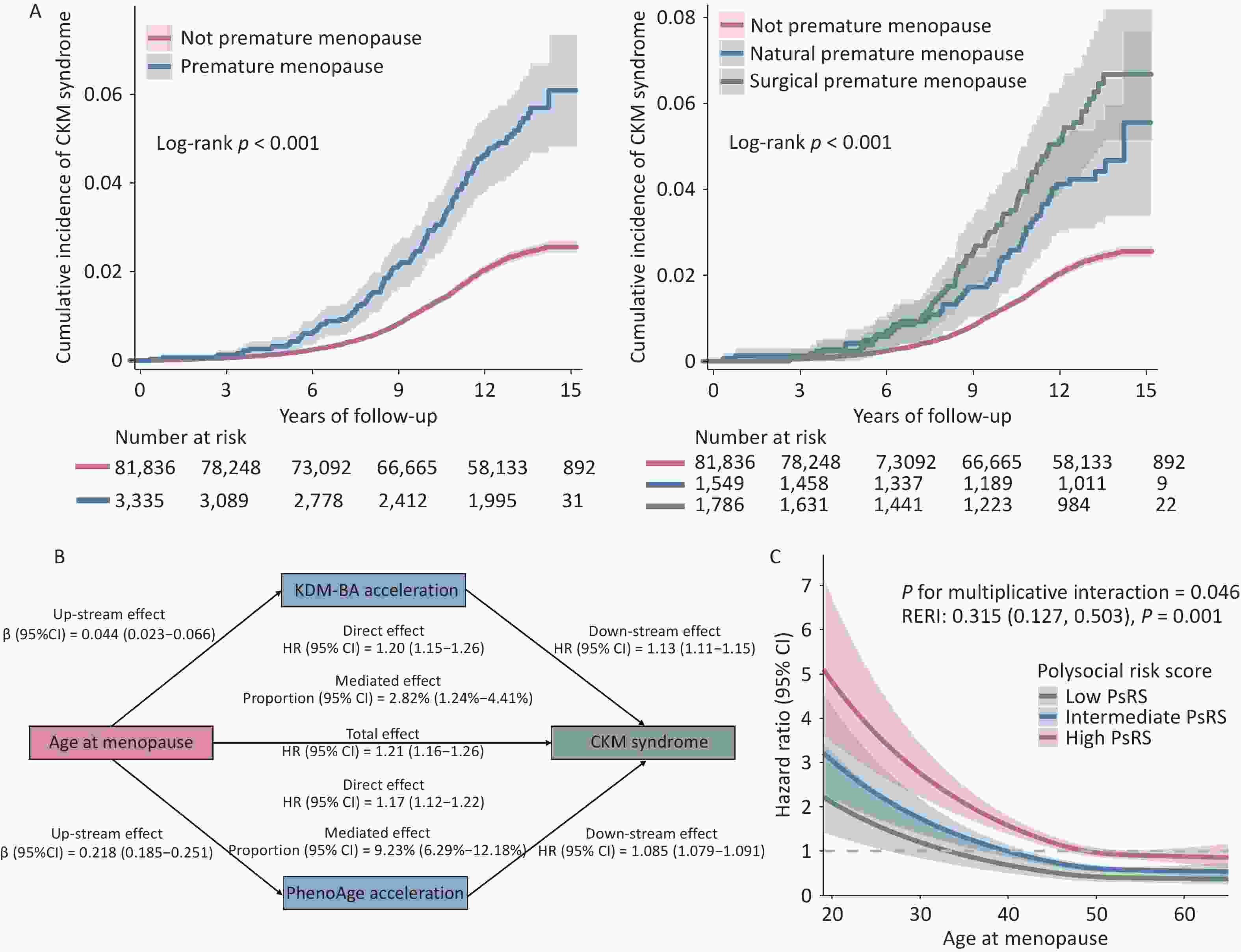

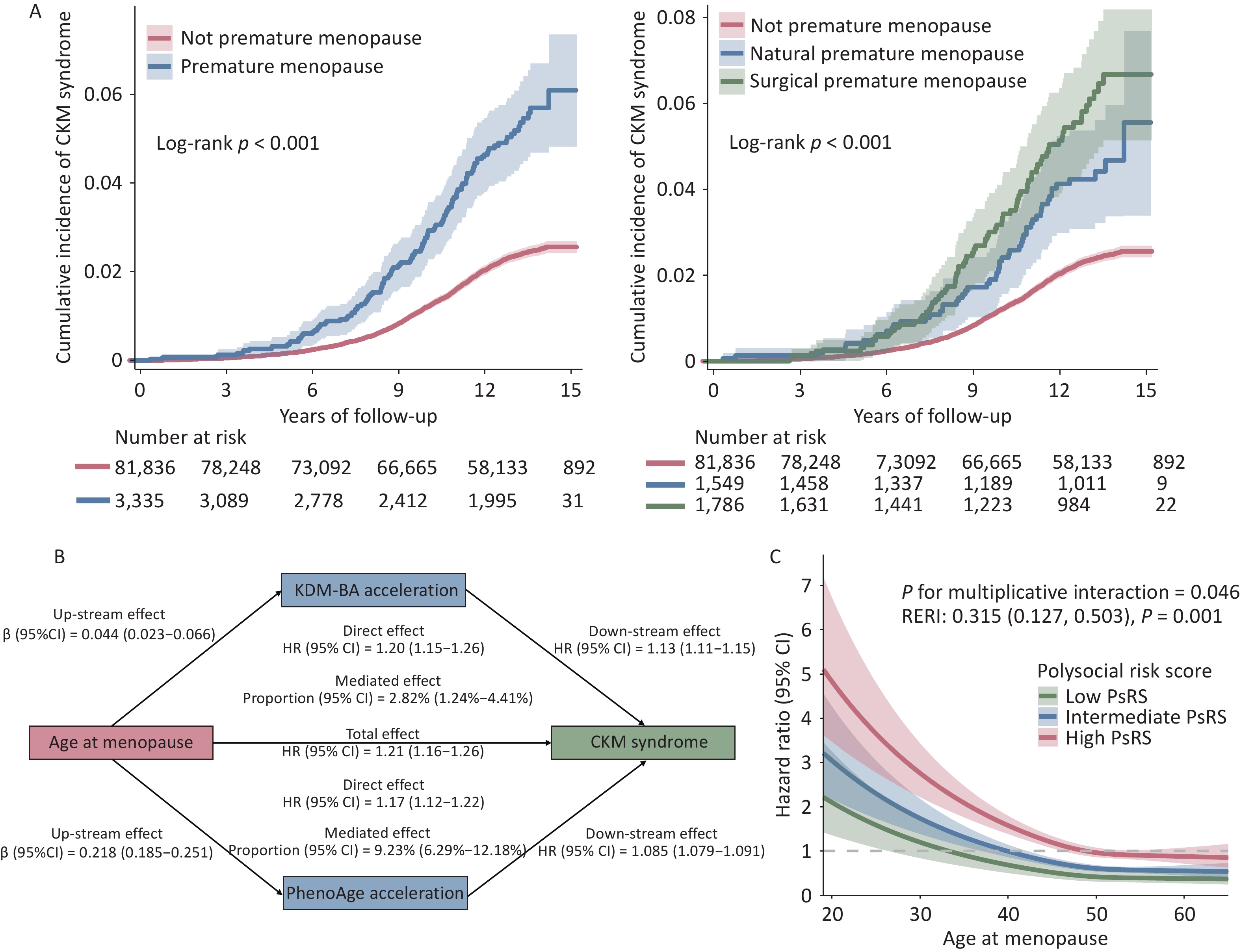

Characteristics Overall (N = 86,904) Incident CKM syndrome P value No (n = 85,217) Yes (n = 1,687) Age at recruitment, years 59.88 ± 5.46 59.82 ± 5.46 63.12 ± 4.76 < 0.001 Body mass index, kg/m2 27.50 ± 5.14 27.41 ± 5.08 32.16 ± 5.93 < 0.001 Ethnicity, White British 78,104 (90.0) 76,590 (90.0) 1,514 (89.9) 0.889 Education < 0.001 Work-related practical qualifications 4,103 (4.7) 4,014 (4.7) 89 (5.3) Lower secondary education 24,347 (28.0) 23,916 (28.1) 431 (25.5) Upper secondary education 9,797 (11.3) 9,661 (11.3) 136 (8.1) Higher education 32,940 (37.9) 32,502 (38.1) 438 (26.0) None of the above 15,717 (18.1) 15,124 (17.7) 593 (35.2) Employment < 0.001 Engaged in paid employment or self-employed 41,165 (47.6) 40,744 (48.0) 421 (25.0) Not engaged in paid employment 5,901 (6.8) 5,741 (6.8) 160 (9.5) Retired 39,419 (45.6) 38,319 (45.2) 1,100 (65.4) Smoking status < 0.001 Current 6,905 (8.0) 6,662 (7.8) 243 (14.4) Previous 30,433 (35.1) 29,754 (35.0) 679 (40.4) Never 49,357 (56.9) 48,597 (57.2) 760 (45.2) Healthy alcohol intake† 40,329 (46.4) 39,738 (46.6) 591 (35.1) < 0.001 Healthy diet† 15,478 (17.9) 15,230 (17.9) 248 (14.8) 0.001 Healthy physical activity† 59,341 (69.3) 58,425 (69.5) 916 (56.1) < 0.001 Family history of diabetes 19,568 (22.52) 19,102 (22.42) 466 (27.62) < 0.001 Family history of heart disease 68,618 (78.96) 67,244 (78.91) 1,374 (81.45) 0.011 Age at menopause, years 49.73 ± 5.12 49.75 ± 5.09 48.67 ± 6.33 < 0.001 Premature menopause 3,470 (4.0) 3,340 (3.9) 130 (7.7) < 0.001 Menopause status < 0.001 Not premature 83,434 (96.0) 81,877 (96.1) 1,557 (92.3) Natural premature 1,588 (1.8) 1,534 (1.8) 54 (3.2) Surgical premature 1,882 (2.2) 1,806 (2.1) 76 (4.5) KDM-BA, years 54.34 ± 6.07 54.24 ± 6.04 59.22 ± 5.52 < 0.001 KDM-BA acceleration, years −5.55 ± 3.27 −5.58 ± 3.25 −3.90 ± 3.67 < 0.001 PhenoAge, years 48.13 ± 7.78 47.96 ± 7.69 56.28 ± 8.01 < 0.001 PhenoAge acceleration, years −11.76 ± 5.31 −11.85 ± 5.23 −6.84 ± 6.90 < 0.001 Polysocial risk score < 0.001 Low (≤ 3) 6,793 (7.8) 6,749 (7.9) 44 (2.6) Intermediate (4–6) 32,087 (36.9) 31,684 (37.2) 403 (23.9) High (≥ 7) 48,024 (55.3) 46,784 (54.9) 1,240 (73.5) Note.. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). †Healthy alcohol intake: alcohol consumption ≤ 14 g/day; Healthy diet: fruit ≥ 3 servings/day, vegetables ≥ 3 servings/day, fish ≥ 2 servings/week, processed meat ≤ 1 serving/week, and unprocessed meat ≤ 1.5 servings/week; Healthy physical activity: moderate activity ≥ 150 minutes/week, vigorous activity ≥ 75 minutes/week, or an equivalent combination. Abbreviations: CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; KDM-BA, Klemera–Doubal biological age. As shown in Table 2, premature menopause was strongly associated with CKM syndrome (HR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.52–2.21) after multivariable adjustment. While surgical menopause initially showed a stronger association than natural menopause (HR = 2.66 vs. 1.94 in crude models), this difference attenuated after full adjustment (HR = 1.80 vs. 1.89). Each SD increase in age at menopause was associated with an 18% reduction in CKM syndrome risk (P for trend < 0.001). The relationship between age at menopause and CKM syndrome appeared largely linear rather than nonlinear (P for nonlinearity = 0.0012). Kaplan–Meier curves (Figure 1A) further illustrated a higher cumulative incidence of CKM syndrome among women with premature menopause, with surgical menopause showing the highest risk over time. These findings extend existing evidence linking early menopause to CVD. A meta-analysis involving 12,519 women revealed a 1.61-fold increased risk of CVD among those with menopause before 40 years of age[8]. Our results indicate that this elevated risk extends beyond CVD to the broader CKM syndrome, positioning premature menopause as a significant systemic risk factor for multi-organ dysfunction.

Table 2. Associations between menopause status, accelerated biological aging, and polysocial risk score with incident CKM syndrome

Cases (person-years) HR (95% CI) Crude Model 1† Model 2‡ Premature menopause No 1,557 (938,966) Ref Ref Ref Yes 130 (35,540) 2.31 (1.93–2.76) 1.96 (1.63–2.36) 1.80 (1.50–2.17) Menopause status Not premature 1,557 (938,966) Ref Ref Ref Natural premature 54 (17,119) 1.94 (1.48–2.55) 2.02 (1.53–2.67) 1.89 (1.43–2.50) Surgical premature 76 (18,422) 2.66 (2.11–3.35) 1.92 (1.52–2.44) 1.75 (1.38–2.22) Per SD age at menopause increase 0.81 (0.77–0.84) 0.80 (0.77–0.84) 0.82 (0.79–0.86) P for trend < 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 P for non-linear < 0.001 0.0011 0.0012 KDM–BA acceleration Per SD increase 1.67 (1.60–1.74) 1.53 (1.46–1.60) 1.50 (1.43–1.57) P for trend < 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 PhenoAge acceleration Per SD increase 1.61 (1.59–1.64) 1.56 (1.52–1.61) 1.56 (1.51–1.61) P for trend < 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 Polysocial risk score Low (≤ 3) 44 (82,034) Ref. Ref. Intermediate (4–6) 403 (372,888) 2.06 (1.51–2.81) 1.47 (1.07–2.02) High (≥ 7) 1240 (519,585) 4.69 (3.47–6.34) 2.39 (1.75–3.26) Each point increase 1.33 (1.30–1.36) 1.19 (1.16–1.21) P for trend < 0.001 < 0.001 Note. †Model 1: adjusted for age at recruitment, body mass index, ethnicity, alcohol intake, smoking status, healthy diet status, physical activity, and family history of diabetes and heart disease. ‡Model 2: Model 1 + education and employment. Abbreviations: CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; KDM-BA, Klemera-Doubal biological age.

Figure 1. Association of age at menopause with the risk of CKM syndrome and the roles of accelerated BAs and PsRS in this association.

Accelerated BAs were consistently associated with a higher risk of CKM syndrome. Each SD increase in KDM-BA and PhenoAge accelerations was linked to a 51% (95% CI: 44%–58%) and 56% (95% CI: 51%–61%) higher risk of CKM syndrome, respectively (Table 2). Each SD decrease in age at menopause increased CKM syndrome risk by 22% (95% CI: 17%–27%), accompanied by increases in KDM-BA acceleration of 0.048 years (95% CI: 0.026–0.069) and in PhenoAge acceleration of 0.221 years (95% CI: 0.188–0.255). PhenoAge acceleration mediated 9.22% (95% CI: 6.32%–12.12%) of the association between earlier menopause and CKM syndrome, while the mediation effect via KDM-BA acceleration was relatively modest (Figure 1B). These findings suggest that premature menopause may contribute to accelerated biological aging, which in turn partially increases the risk of CKM syndrome. However, the relatively small proportion of the effect mediated by BA implies that additional biological or social pathways are likely involved. Existing evidence indicates that insulin resistance and systemic inflammation, driven by the abrupt decline in estrogen, play central roles in the pathogenesis of CKM syndrome[9]. Future studies should employ multi-omics approaches or interventional designs to elucidate further these mechanisms.

Moreover, adverse SDOH substantially increased the risk of CKM syndrome, with HRs for individual risk factors ranging from 1.18 (social inactivity) to 1.83 (low household income) (Supplementary Table S5). After multivariable adjustment, participants with an intermediate PsRS (HR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.07–2.02) and high PsRS (HR = 2.42, 95% CI: 1.77–3.29) had a higher risk of CKM syndrome than did those with a low PsRS. Each 1-point increase in the PsRS was associated with a 19% (95% CI: 16%–22%) higher risk of CKM syndrome (P for trend < 0.001). Stratified analysis revealed that higher polysocial risk amplified the increased CKM syndrome risk associated with premature menopause (Table 2). This synergistic effect was supported by a significant additive interaction (RERI = 0.315, SI = 0.238, AP = 0.598) (Supplementary Table S6) and multiplicative interaction (P = 0.042) (Figure 1C). In addition, the associations of menopause status, BA acceleration, and PsRS with CKM syndrome remained robust after accounting for competing risks of mortality and loss to follow-up (Supplementary Table S7), as well as across different CKM stages (Supplementary Table S8). Previous evidence has linked individual SDOH to specific components of CKM syndrome, but the interplay between social and biological factors in its etiology remains unclear[1]. By constructing a PsRS encompassing multiple domains, we identified an interactive effect between premature menopause and PsRS on CKM syndrome risk. This highlights the clinical and public health importance of developing targeted screening and intervention strategies for socially high-risk menopausal women to reduce the CKM health burden.

A major strength of this study is that the large sample size and comprehensive data collection of the UK Biobank allowed us to examine the association between premature menopause and CKM syndrome, as well as the mediating role of AAs and the modifying effect of the PsRS. In addition, adjustment for a wide range of covariates, including demographic characteristics and lifestyle factors, helped to reduce effectively the influence of potential confounders. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, self-reported age at menopause might be subject to recalling bias; however, prior evidence has demonstrated good validity and reproducibility of such data[10]. Second, the included postmenopausal women tended to have a higher BMI, socioeconomic status, and healthier lifestyle patterns than the excluded women (Supplementary Table S9), which might affect the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Third, because this was an observational study, causal relationships cannot be established. Finally, the modest mediation effects of BA suggest that other biological mechanisms—such as inflammation, insulin resistance, or hormonal pathways—may contribute to the observed associations. Future research integrating multi-omics approaches or interventional designs is warranted to clarify these mechanisms and inform tailored preventive strategies.

This large prospective cohort demonstrates that premature menopause, whether natural or surgical, significantly increases the risk of CKM syndrome. AAs partially mediated the elevated risk of CKM syndrome associated with earlier menopause, and a synergistic effect was observed between premature menopause and higher polysocial risk. These findings provide novel insights into the mechanisms linking premature menopause and CKM syndrome and highlight the importance of developing screening tools and interventions addressing social risk factors to promote CKM health.

doi: 10.3967/bes2026.002

Associations Between Premature Menopause and Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study from the UK Biobank

-

Writing–original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Conceptualization: Ming Jin, Nan Li, and Xiaojing Liu; Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization: Zeping Yang and Ziyi Zhang; Methodology, Conceptualization: Zhexin Luo and Ninghao Huang; Source, Project administration, Data curation: Tao Huang; Writing–review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition: Nan Li and Xiaojing Liu; Writing–review & editing, Data curation, Conceptualization, Project administration: Nan Li and Xiaojing Liu.

None.

The UK Biobank study was approved by the North West Multi-centre Research Ethical Committee (No. 11/NW/0382), and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

注释:1) Authors’ Contributions: 2) Competing Interests: 3) Ethics: -

Figure 1. Association of age at menopause with the risk of CKM syndrome and the roles of accelerated BAs and PsRS in this association.

(A) Kaplan–Meier curves showing the cumulative incidence of CKM syndrome by premature menopause status. (B) Mediation analyses estimating the mediating role of accelerated BAs in the association between age at menopause and CKM syndrome risk. (C) Restricted cubic spline models assessing the dose-dependent relationship between PsRS and CKM syndrome risk. Abbreviations: CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; BA, biological age; PsRS, polysocial risk score; KDM-BA, Klemera–Doubal method biological age; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants according to CKM syndrome

Characteristics Overall (N = 86,904) Incident CKM syndrome P value No (n = 85,217) Yes (n = 1,687) Age at recruitment, years 59.88 ± 5.46 59.82 ± 5.46 63.12 ± 4.76 < 0.001 Body mass index, kg/m2 27.50 ± 5.14 27.41 ± 5.08 32.16 ± 5.93 < 0.001 Ethnicity, White British 78,104 (90.0) 76,590 (90.0) 1,514 (89.9) 0.889 Education < 0.001 Work-related practical qualifications 4,103 (4.7) 4,014 (4.7) 89 (5.3) Lower secondary education 24,347 (28.0) 23,916 (28.1) 431 (25.5) Upper secondary education 9,797 (11.3) 9,661 (11.3) 136 (8.1) Higher education 32,940 (37.9) 32,502 (38.1) 438 (26.0) None of the above 15,717 (18.1) 15,124 (17.7) 593 (35.2) Employment < 0.001 Engaged in paid employment or self-employed 41,165 (47.6) 40,744 (48.0) 421 (25.0) Not engaged in paid employment 5,901 (6.8) 5,741 (6.8) 160 (9.5) Retired 39,419 (45.6) 38,319 (45.2) 1,100 (65.4) Smoking status < 0.001 Current 6,905 (8.0) 6,662 (7.8) 243 (14.4) Previous 30,433 (35.1) 29,754 (35.0) 679 (40.4) Never 49,357 (56.9) 48,597 (57.2) 760 (45.2) Healthy alcohol intake† 40,329 (46.4) 39,738 (46.6) 591 (35.1) < 0.001 Healthy diet† 15,478 (17.9) 15,230 (17.9) 248 (14.8) 0.001 Healthy physical activity† 59,341 (69.3) 58,425 (69.5) 916 (56.1) < 0.001 Family history of diabetes 19,568 (22.52) 19,102 (22.42) 466 (27.62) < 0.001 Family history of heart disease 68,618 (78.96) 67,244 (78.91) 1,374 (81.45) 0.011 Age at menopause, years 49.73 ± 5.12 49.75 ± 5.09 48.67 ± 6.33 < 0.001 Premature menopause 3,470 (4.0) 3,340 (3.9) 130 (7.7) < 0.001 Menopause status < 0.001 Not premature 83,434 (96.0) 81,877 (96.1) 1,557 (92.3) Natural premature 1,588 (1.8) 1,534 (1.8) 54 (3.2) Surgical premature 1,882 (2.2) 1,806 (2.1) 76 (4.5) KDM-BA, years 54.34 ± 6.07 54.24 ± 6.04 59.22 ± 5.52 < 0.001 KDM-BA acceleration, years −5.55 ± 3.27 −5.58 ± 3.25 −3.90 ± 3.67 < 0.001 PhenoAge, years 48.13 ± 7.78 47.96 ± 7.69 56.28 ± 8.01 < 0.001 PhenoAge acceleration, years −11.76 ± 5.31 −11.85 ± 5.23 −6.84 ± 6.90 < 0.001 Polysocial risk score < 0.001 Low (≤ 3) 6,793 (7.8) 6,749 (7.9) 44 (2.6) Intermediate (4–6) 32,087 (36.9) 31,684 (37.2) 403 (23.9) High (≥ 7) 48,024 (55.3) 46,784 (54.9) 1,240 (73.5) Note.. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). †Healthy alcohol intake: alcohol consumption ≤ 14 g/day; Healthy diet: fruit ≥ 3 servings/day, vegetables ≥ 3 servings/day, fish ≥ 2 servings/week, processed meat ≤ 1 serving/week, and unprocessed meat ≤ 1.5 servings/week; Healthy physical activity: moderate activity ≥ 150 minutes/week, vigorous activity ≥ 75 minutes/week, or an equivalent combination. Abbreviations: CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; KDM-BA, Klemera–Doubal biological age. Table 2. Associations between menopause status, accelerated biological aging, and polysocial risk score with incident CKM syndrome

Cases (person-years) HR (95% CI) Crude Model 1† Model 2‡ Premature menopause No 1,557 (938,966) Ref Ref Ref Yes 130 (35,540) 2.31 (1.93–2.76) 1.96 (1.63–2.36) 1.80 (1.50–2.17) Menopause status Not premature 1,557 (938,966) Ref Ref Ref Natural premature 54 (17,119) 1.94 (1.48–2.55) 2.02 (1.53–2.67) 1.89 (1.43–2.50) Surgical premature 76 (18,422) 2.66 (2.11–3.35) 1.92 (1.52–2.44) 1.75 (1.38–2.22) Per SD age at menopause increase 0.81 (0.77–0.84) 0.80 (0.77–0.84) 0.82 (0.79–0.86) P for trend < 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 P for non-linear < 0.001 0.0011 0.0012 KDM–BA acceleration Per SD increase 1.67 (1.60–1.74) 1.53 (1.46–1.60) 1.50 (1.43–1.57) P for trend < 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 PhenoAge acceleration Per SD increase 1.61 (1.59–1.64) 1.56 (1.52–1.61) 1.56 (1.51–1.61) P for trend < 0.001 <0.001 <0.001 Polysocial risk score Low (≤ 3) 44 (82,034) Ref. Ref. Intermediate (4–6) 403 (372,888) 2.06 (1.51–2.81) 1.47 (1.07–2.02) High (≥ 7) 1240 (519,585) 4.69 (3.47–6.34) 2.39 (1.75–3.26) Each point increase 1.33 (1.30–1.36) 1.19 (1.16–1.21) P for trend < 0.001 < 0.001 Note. †Model 1: adjusted for age at recruitment, body mass index, ethnicity, alcohol intake, smoking status, healthy diet status, physical activity, and family history of diabetes and heart disease. ‡Model 2: Model 1 + education and employment. Abbreviations: CKM, cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; KDM-BA, Klemera-Doubal biological age. -

[1] Ndumele CE, Rangaswami J, Chow SL, et al. Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2023; 148, 1606−35. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001184 [2] Muka T, Oliver-Williams C, Kunutsor S, et al. Association of age at onset of menopause and time since onset of menopause with cardiovascular outcomes, intermediate vascular traits, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol, 2016; 1, 767−76. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.2415 [3] Muka T, Asllanaj E, Avazverdi N, et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetologia, 2017; 60, 1951−60. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4346-8 [4] Qian D, Wang ZF, Cheng YC, et al. Early menopause may associate with a higher risk of CKD and all-cause mortality in postmenopausal women: an analysis of NHANES, 1999-2014. Front Med, 2022; 9, 823835. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.823835 [5] Honigberg MC, Zekavat SM, Aragam K, et al. Association of premature natural and surgical menopause with incident cardiovascular disease. JAMA, 2019; 322, 2411−21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19191 [6] Levine ME, Lu AT, Chen BH, et al. Menopause accelerates biological aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2016; 113, 9327−32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604558113 [7] Zhao YM, Li YY, Zhuang ZH, et al. Associations of polysocial risk score, lifestyle and genetic factors with incident type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetologia, 2022; 65, 2056−65. doi: 10.1007/s00125-022-05761-y [8] Roeters van Lennep JE, Heida KY, Bots ML, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with premature ovarian insufficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2016; 23, 178−86. doi: 10.1177/2047487314556004 [9] Chen YW, Lian WB, Wu LZ, et al. Joint association of estimated glucose disposal rate and systemic inflammation response index with mortality in cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome stage 0-3: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2025; 24, 147. doi: 10.1186/s12933-025-02692-x [10] Xu ZW, Chung HF, Dobson AJ, et al. Menopause, hysterectomy, menopausal hormone therapy and cause-specific mortality: cohort study of UK Biobank participants. Hum Reprod, 2022; 37, 2175−85. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deac137 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links