-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous pulmonary disorder characterized by symptoms such as breathlessness, chronic cough, sputum expectoration, and recurrent exacerbations. These clinical features stem from structural changes, including bronchitis and bronchiolitis involving the airways and emphysema affecting the alveoli, collectively causing irreversible airflow limitation that typically worsens over time[1]. It is currently the third most prevalent contributor to global mortality[1]. The emergence and progression of COPD has caused a significant and growing economic and social burden, making it one of the principal causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide[2]. However, considerable uncertainty remains regarding its etiology and pathogenesis.

Cigarette smoke (CS) exposure is a principal contributor to the onset and progression of COPD[3]. Numerous studies have established that COPD is a significant determinant of coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and lung malignancies[4-8]. CS, which contains numerous cytotoxic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic agents[9], contributes to incompletely reversible airflow limitation, airway remodeling, and emphysema in COPD through uncontrolled and chronic inflammatory responses[10]. Consequently, elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms of emphysema and paving the way for novel therapeutic approaches are fundamental to improving the prognosis of patients with COPD.

Ferroptosis, first identified by Dixon et al. in their seminal 2012 study, is marked by lipid peroxidation and frequently associated with iron-dependent non-apoptotic cell death[11,12]. It is regulated by several factors, including the glutathione (GSH) synthesis pathway, iron homeostasis, and lipid metabolism[11,13,14]. Research has demonstrated that ferroptosis is implicated in numerous pathological processes, including neurodegenerative diseases, hemochromatosis-related hepatic tissue damage, and malignant tumors[15-17]. Studies have demonstrated an association between ferroptosis and lung diseases such as pulmonary fibrotic disease[18] and acute lung injury (ALI)[19]. According to Yoshida et al.[20], CS exposure can contribute to COPD by disrupting pulmonary iron homeostasis, which causes ferroptosis in human bronchial epithelium and promotes disease progression.

Multiple mechanisms are involved in ferroptosis, with amino acid metabolism being one of the key factors. The cystine/glutamate transporter system (system Xc-) consists of two membrane transporters: solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2) and solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), with SLC7A11 serving as a functional subunit[21]. The system Xc- facilitates the import of extracellular cystine by exchanging it with intracellular glutamate; cystine is converted to cysteine, thereby providing a determining substrate for GSH production[22]. Inhibition of system Xc- suppresses cystine uptake, thereby reducing GSH synthesis, decreasing glutathione peroxidase activity, weakening antioxidant capacity, and causing accumulation of lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS), ultimately leading to oxidative damage and ferroptosis[11].

Cytochrome P450 epoxygenase isozymes catalyze the conversion of arachidonic acid to produce epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs)[23]. Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), encoded by the Ephx2 gene, hydrolyzes EETs to reduce the biological potency of dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids[24]. Smith et al.[25] showed that sEH inhibitors could reduce airway inflammation caused by CS exposure. Hu et al.[26] demonstrated that CS-induced atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling were significantly reduced in Ephx2 null (Ephx2-/-) mice. Luo et al.[27] reported that EETs can mitigate lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced ALI by reducing ROS levels. In patients with COPD, sEH inhibitors have been suggested to protect against lung injury caused by repeated subacute CS stimulation[28]. These findings indicate that sEH is involved in COPD airway inflammation and implicated in the pathogenesis and development of the disease. However, the exact mechanism by which Ephx2 disrupts COPD remains unclear. Further research is warranted to establish whether ferroptosis regulation influences the pathophysiology of COPD. Therefore, we used Ephx2 knockout (Ephx2-/-, KO), wild-type (WT), and CS-induced COPD models to investigate whether Ephx2 deficiency affects the pathophysiological mechanisms of COPD by regulating ferroptosis.

-

Ephx2-/- C57BL/6J male mice were obtained from Professor Yi Zhu Laboratory (Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, China) and maintained in a room under constant humidity and temperature conditions, subjected to 12-h photoperiod, and provided with standard chow and tap water ad libitum. DNA was extracted from the tails of mice, and the murine genotype was identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described previously[29]. The primers used were as follows: 5’-TGG CAC GAC CCT AAT CTT AGG TTC-3’ (F1); 5’-TGC ACG CTG GCA TTT TAA CAC CAG-3’ (R1); 5’-CCA ATG ACA AGA CGC TGG GCG-3’ (R2). The amplification protocol consisted of an initial denaturation (94 °C, 5 min), followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s. Screening was performed according to the following criteria: F1/R1 primer pair: WT, 338 bp; F1/R2 primer pair: Ephx2 deletion, 295 bp[30]. Primers were designed by the Beijing Tianyi Huiyuan Life Science & Technology, Inc. (Beijing, China). The animal studies and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Beijing Friendship Hospital of Capital Medical University (15-2001). All animals were treated in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

-

An experimental model of COPD was established by exposing mice to CS. WT and Ephx2-/- mice (22 g; 6–8 weeks old) were randomly assigned to the control and CS-exposure groups (n = 6 per group). WT and KO control groups were exposed to ambient air. The WT-CS and KO-CS groups were exposed to CS using a whole-body exposure system (Jiangjun cigarettes, 11 mg tar, 0.84 mg nicotine). Mice were placed in a smoke exposure device (patented utility model, Patent No. ZL 201820283572.9, Wu Yanjun), and CS was drawn into the device using a negative pressure pump. Fifteen standard cigarettes were burnt for 2 h per session, with daily exposure (5 days/week) for 16 consecutive weeks. The mice were weighed every two weeks.

-

Pulmonary function was examined using a FlexiVent system (SCIREQ, Montreal, QC, Canada). After 16 weeks of sustained CS/air exposure, mice were anesthetized using 4% tribromoethanol (0.2 mg/kg intraperitoneally; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and subsequently intubated with a 20G cannula; the other end of the catheter was connected to the pulmonary function instrument for a small-animal ventilator. Mechanical ventilation was administered (tidal volume, 10 mL/kg; respiratory rate, 150 breaths/min; positive end-expiratory pressure, 3 cm H2O). Pulmonary function was measured using the Forced Oscillation Technique (FOT) system. Single FOT measurements were performed to determine respiratory system resistance (Rrs), respiratory system compliance (Crs), Newtonian resistance (Rn), tissue damping (G), and tissue elastance (H). Upon completion of the test, mice were allowed to recover under warm and oxygen-enriched conditions. Water and food were provided 1 h after recovery.

-

Upon completion of the 16-week CS or air exposure protocol, mice were euthanized via an anesthetic overdose, and blood was collected via enucleation of the eyeballs. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature (22 ± 2 °C), blood samples were kept under refrigeration (4 °C) for 2 h. Immediately after blood collection, BALF was collected using an 18G tracheal cannula (Boruida, Shanghai, China). A 1 ml syringe was used to instill 0.5 mL of 0.9% saline for bronchoalveolar lavage, and the procedure was repeated five times. BALF was centrifuged at 1800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Supernatants were collected, portioned, and maintained at -80 °C for further analysis. Cells obtained from the BALF were resuspended by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and test immediately.

-

After euthanasia, lungs and tracheas of mice were excised. Each lung lobe was completely resected and labeled separately. Most samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen after being transferred to sterile 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes and cryopreserved at −80 °C for subsequent experiments. Part of the right upper lobe was perfused with 50% optimal cutting temperature (OCT)-PBS solution, and sections were prepared for electron microscopy. The middle lobes of the right lungs were fixed for 7–10 days by inflation with 4% paraformaldehyde at a constant pressure of 25 cm H2O.

Lung tissues were embedded in paraffin (SPI Supplies, West Chester, PA, USA) using Tissue Embedding Stations for Histology (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), sectioned into 5 μm-thick sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), according to the manufacturer's protocol (Solarbio Science & Technology, Beijing, China). Emphysema was determined by measuring alveolar size using the mean linear intercept (MLI). Fifteen regions were randomly selected from × 200 magnification tissue sections and analyzed using a semi-automated measurement method[31]. The mean alveolar number (MAN) was calculated to evaluate emphysema severity.

-

Mice exposed to CS for 16 weeks were identified by lung function testing. Following total RNA extraction, RNA quality was assessed using the RNA 6000 Nano Kit and Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and bioinformatic analyses were conducted by Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

-

TUNEL assays were conducted using the DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The paraffin-embedded lung tissues were sectioned for subsequent experiments. After dewaxing and rehydration, the sections were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized using Proteinase K, and washed three times with PBS. After a 10-min equilibration in buffer, sections were washed, and incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase enzymes (37 °C, 1 h) in a humid chamber. Nuclear staining was performed using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The slides were washed, mounted in antifade medium, and analyzed using confocal microscopy (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) at 488 and 510 nm.

-

MDA and SOD, by-products of lipid peroxidation, were quantified using commercially available assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). BALF and serum iron contents were also quantified.

-

Spectrophotometric measurements of total, reduced, and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) were performed using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). GSH was calculated as follows: (GSH + GSSG) – (2 × GSSG).

-

For the measurement of lipid ROS levels, BALF-derived cells were incubated with 5 μM BODIPY 581/591 C11 (InvitrogenTM D3861, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C for 45 min, washed twice with PBS, and analyzed using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe (#S0033S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Beijing, China) was employed to quantify total ROS levels. Following a 30-min incubation with 10 μM DCFH-DA at 37 °C, the cells were washed and subsequently subjected to flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

-

Frozen lung tissues (20 mg) were homogenized for protein extraction using ice-cold cell lysis buffer, centrifuged at 4 °C and 15,000 × g for 15 min, and processed using a histone extraction kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Nanjing, China). Nuclear proteins were extracted using a Cell Nucleus Protein and Cell Plasma Protein Extraction Kit (P0028; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Nanjing, China). Protein concentrations were measured using the bicinchoninic acid method (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Protein samples (20 μg per lane) were resolved by SDS-PAGE (8% and 12%) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes by electrophoresis at 300 mA for 80 min. After blocking with 5% skim milk or BSA for 2 h at room temperature, the membranes were washed thrice with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), 4-hydroxynonenal (4HNE) (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), ferritin heavy/chain 1 (FTH1) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA,USA), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), SLC7A11 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and β-actin (1:5000; ImmunoWay, Plano, TX, USA). After washing, the membranes were probed with the appropriate secondary antibody (1:5000; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA) for 2 h. Signals were detected by electrochemiluminescence (HY-K1005, MedChemExpress, NJ, USA) using an imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

-

Lung tissues (50 mg) were processed for RNA extraction using TRIzol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). RT-qPCR primers and conditions were as follows: GSS: 5′-GAAGAACTGGCAAAGCAGGC-3′ (F); 5′-CAGAGCACTGGGTACTGGTG-3′ (R), SLC7A11:5′-CTGCAGCTAACTGACTGCCC-3′ (F); 5′-TTTGCTATCACCGACTGGCT-3′ (R), GPX4:5′-GATGGAGCCCATTCCTGAACC-3′ (F); 5′-CCCTGTACTTATCCAGGCAGA-3′ (R), and ACTB: 5′-TGCTTCTAGGCGGACTGTTA-3′ (F); 5′-AACCAACTGCTGTCGCCTTH-3′ (R). PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Reactions were run on an ABI 7500 fast real-time PCR system, and data were analyzed using the 2-△△CT method.

-

Lung tissues perfused with 50% OCT were embedded in 100% OCT using a pre-chilled cryo-embedding medium and maintained at −80 °C. Frozen samples were cryosectioned (5 μm at −20°C), washed, and incubated in 5 μM dihydroethidium staining solution (37 °C, 20 min) in the dark. Sections were rinsed, mounted, and examined using a fluorescence microscope (FV10; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

-

After fixing overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, lung tissue specimens were embedded in paraffin and sectioned (4 μm). Sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, and rinsed with PBS. Antigen retrieval was conducted in EDTA buffer, followed by erythrocyte lysis for 10 min. Following a 1-h block at room temperature in 1% goat serum, sections were incubated with primary antibodies (4HNE, 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK and COX2, 1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 4 °C overnight. After washing, slides were probed with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:500; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclear counterstaining was performed using DAPI, and the slides were mounted with antifade medium. Imaging was performed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV10; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

-

Fresh lung tissues were dissected and immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h, rinsed with PBS, and post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide. Samples were dehydrated, embedded in Agar 100 resin, sectioned (70 nm), and subjected to dual staining with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were imaged using an FEI Morgagni 268D transmission electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands) at 80 kV. Images were captured using an 11-megapixel Morada charge-coupled device camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Mitochondrial structures were examined at 100,000× magnification, and at least three lung tissue specimens per group were analyzed.

-

The sample size (n = 6 per group) was determined based on comparable preclinical studies with similar endpoints[32,33]. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For datasets that passed the homogeneity of variance test, one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. For data that were not normally distributed or failed the variance test, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

-

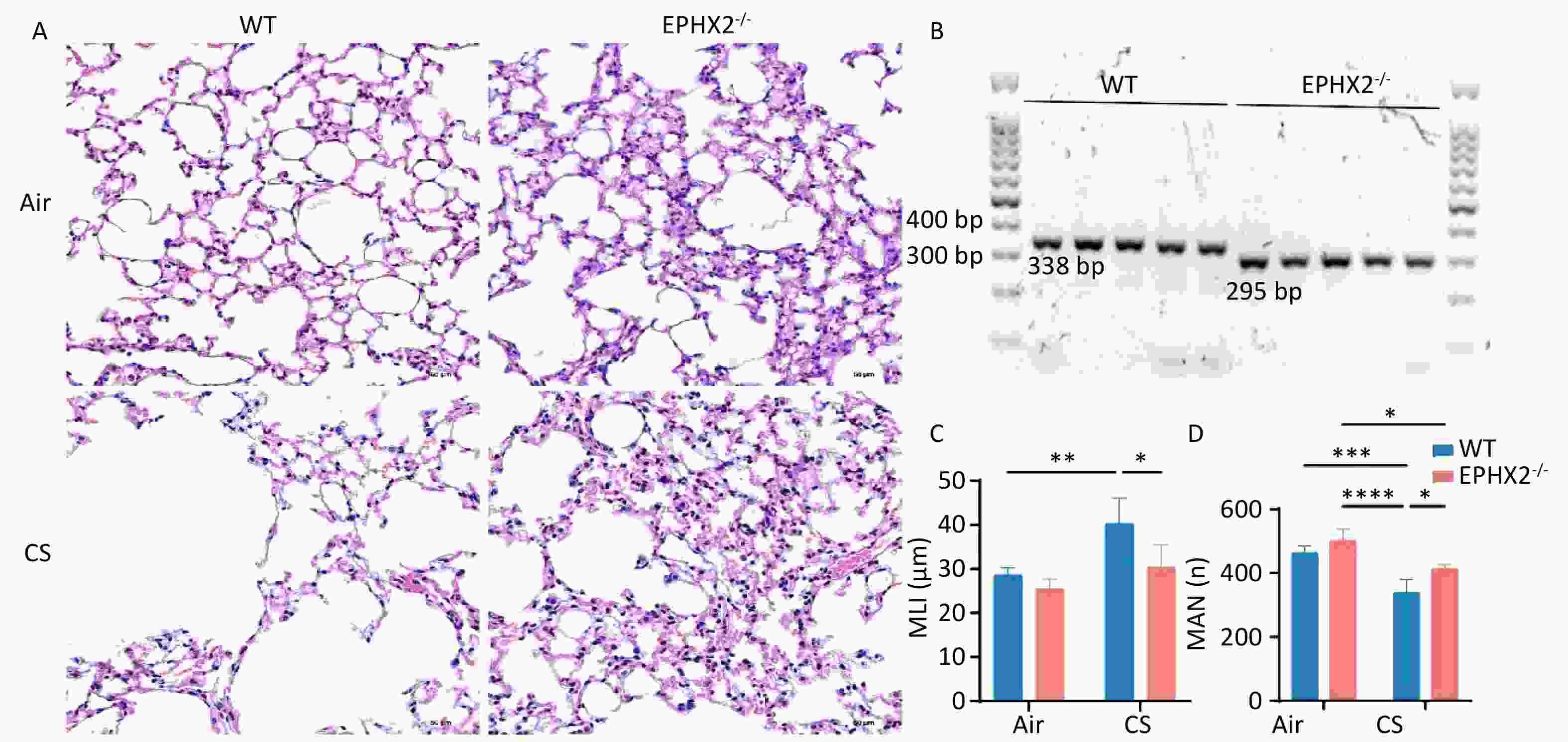

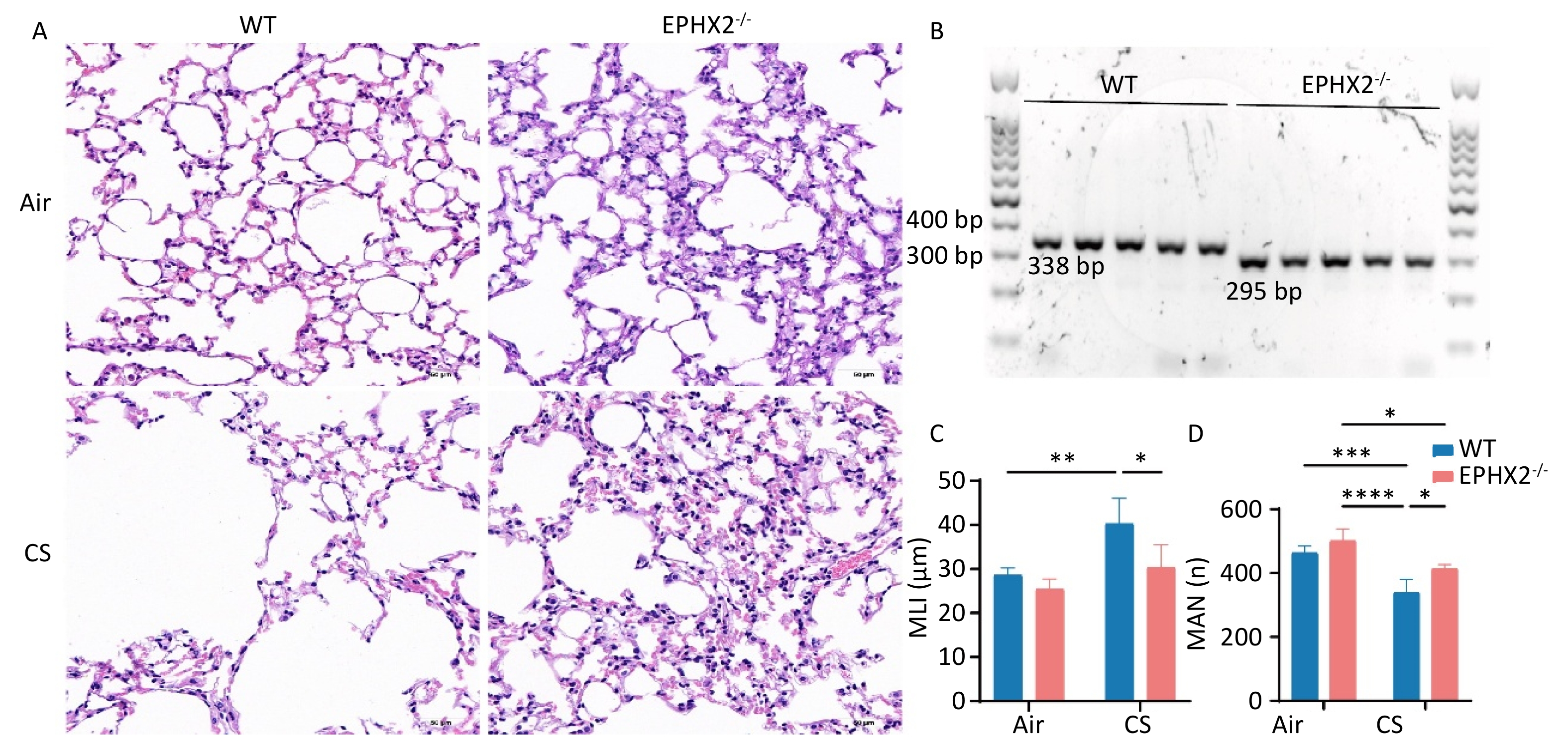

Emphysema, one of the most important manifestations of COPD, primarily involves the airspaces beyond the terminal bronchioles. It is characterized by the destruction and overexpansion of the terminal bronchioles and alveoli[34]. Emphysematous changes were quantified by determining the MLI, and the severity of emphysema was compared across groups of mice. Emphysema was more severe in CS-exposed than in air-exposed mice. Compared with WT + CS mice, the MLI was significantly reduced and the MAN was considerably increased in Ephx2-/- + CS mice. These findings suggest a protective effect against emphysema (Figure 1).

-

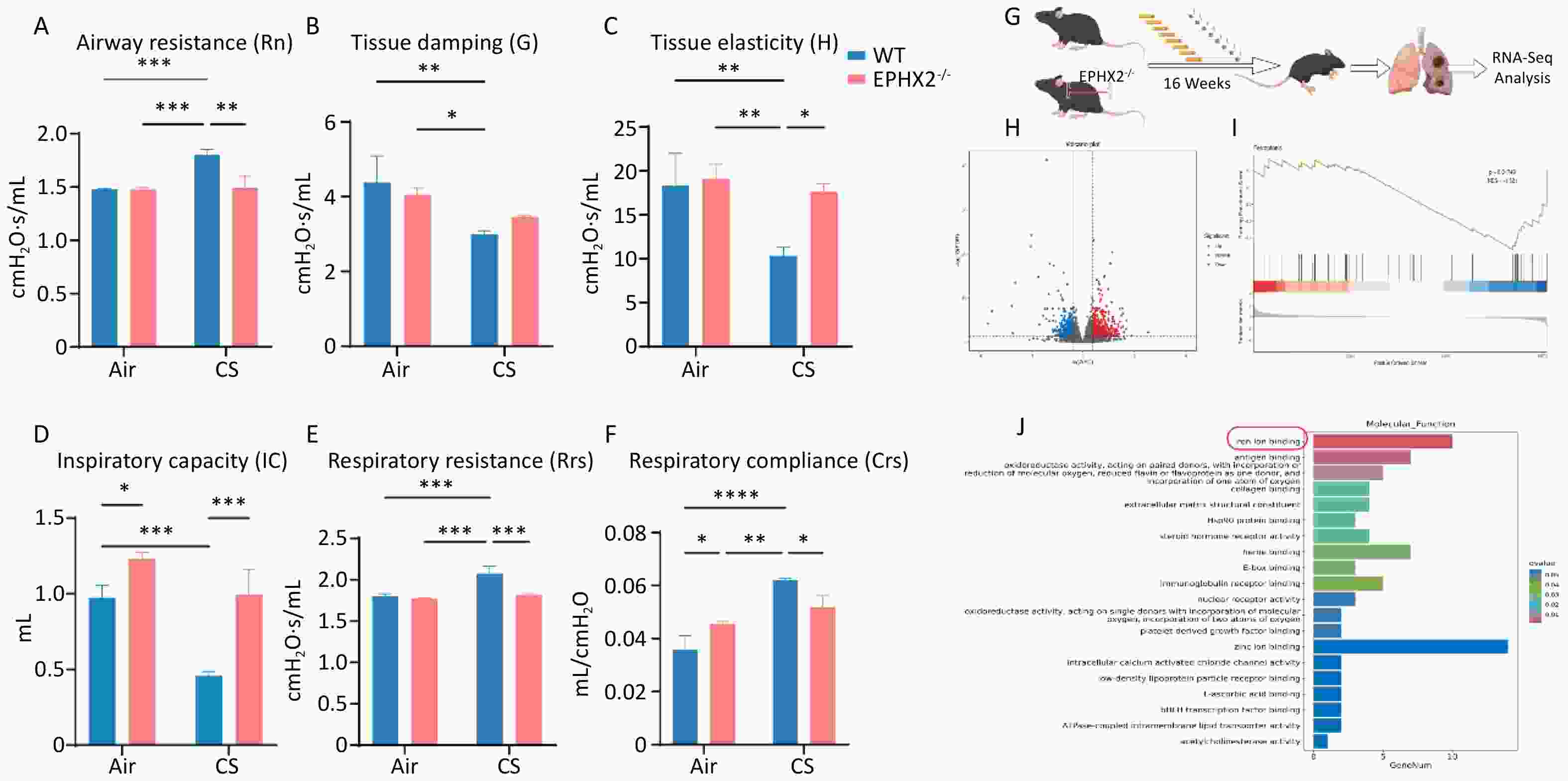

Lung function analysis after 16 weeks of CS exposure demonstrated a substantial elevation in Rrs and Rn in WT mice compared with air-exposed groups, whereas IC and tissue damage (G&H) were significantly lower. After 16 weeks of CS exposure, Rrs and Rn were markedly reduced in Ephx2-/- mice, demonstrating statistically significant differences from WT mice. In addition, IC and tissue damage were greater in Ephx2-/- mice than in WT mice; however, the difference in G was not statistically significant. These data indicate that Ephx2-/- mice were less prone to chronic CS-stimulated increase in Rn (Figure 2A–F).

Figure 2. Ephx2-/- mice showed less lung function impairment via the ferroptosis signaling pathway following CS exposure.

RNA-seq analysis was performed on CS-injured lungs, with or without Ephx2 expression, to identify fundamental molecular changes (Figure 2G). Transcriptomic analysis revealed 753 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), of which 474 were upregulated and 279 were downregulated (Figure 2H). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis showed that the ferroptosis signaling pathway, a well-studied cardioprotective pathway, was significantly modulated by Ephx2 deletion in CS-induced lungs. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) further validated that the absence of Ephx2 suppressed the activation of the ferroptosis signaling pathway in CS-induced emphysema (Figure 2I, 2J). Therefore, we investigated whether Ephx2 expression attenuates CS-induced lung injury through the ferroptosis signaling pathway.

-

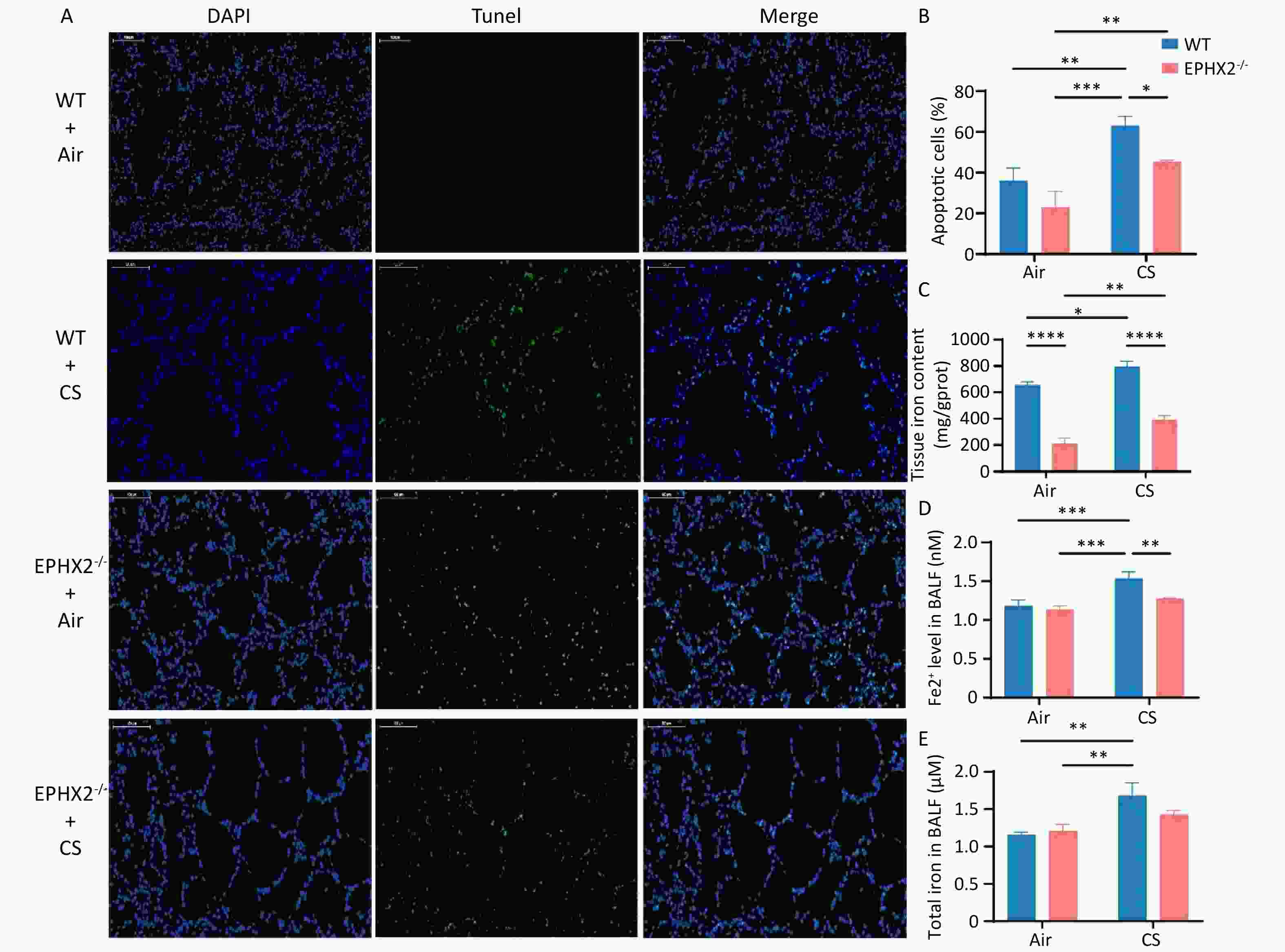

CS induced cell death in normal and COPD lung epithelial cells[2]. Confocal laser scanning microscopy revealed death of airway epithelial cells. TUNEL-positive cells showed condensed and fragmented nuclear DNA in the airway epithelium. Airway epithelial cells were more prone to death in CS-exposed groups than in air-exposed groups. The number of epithelial cell death was significantly reduced in Ephx2-/- + CS groups compared with WT + CS groups (Figure 3A, B).

-

CS exposure increased iron levels in the BALF. Iron content in the BALF was significantly elevated in CS-exposed mice relative to that in air-exposed controls. However, CS-induced elevation in iron levels was lower in Ephx2-/- mice than in WT mice (Figure 3C–E).

-

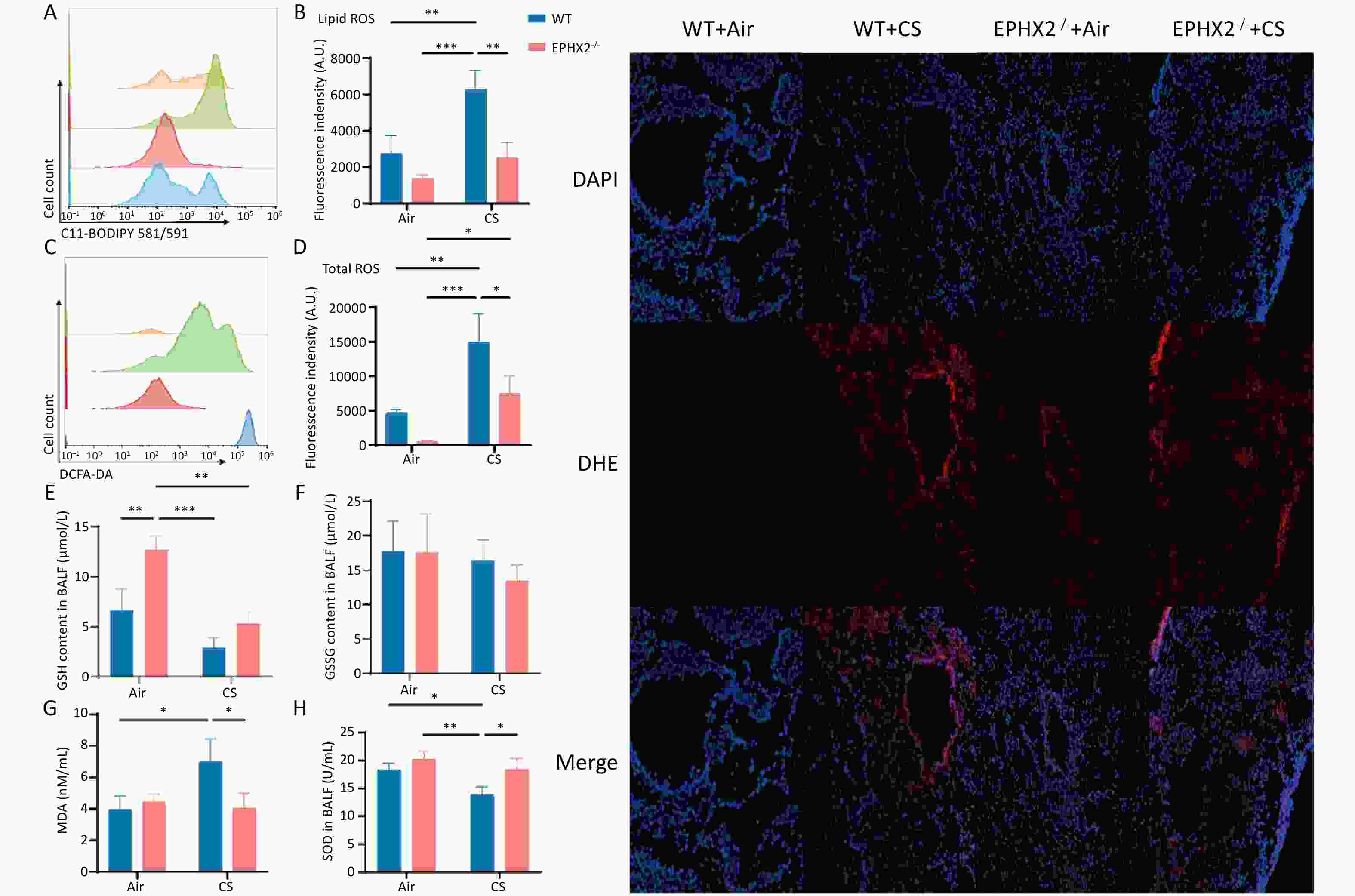

Ferroptosis is characterized by ROS production via iron-mediated Fenton reactions that cause phospholipid peroxidation in the cell membrane[11]. Lipid ROS and total ROS levels were significantly elevated in CS-exposed mice relative to those in air-exposed controls. However, following CS exposure, both measures were lower in Ephx2-/- mice than in WT mice (Figure 4A–D). Total ROS levels were also increased in bronchoalveolar epithelial cells (Figure 4I).

-

Following CS exposure, Ephx2-/- mice exhibited higher GSH and SOD levels and lower MDA levels than those of WT mice. In the BALF, GSH and SOD levels were significantly lower in CS-exposed mice than in air-exposed mice, whereas MDA levels were significantly higher. SOD levels were substantially higher and GSH levels were higher in the BALF, whereas MDA levels were significantly lower in Ephx2-/- mice following CS exposure than in WT mice (Figure 4E–H).

-

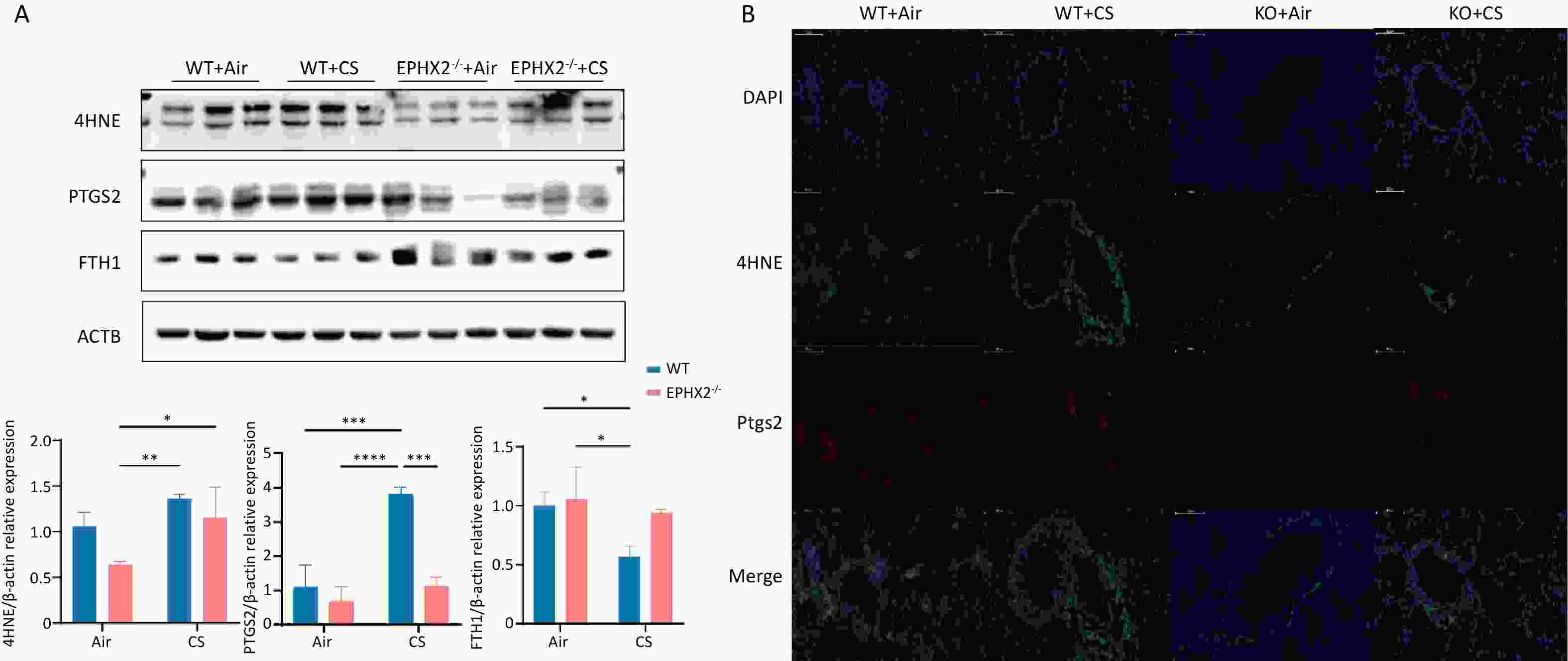

The levels of 4HNE and COX2 in the lung tissue were significantly elevated in CS-exposed mice compared with those in air-exposed controls, whereas FTH1 levels were significantly decreased. Compared with WT + CS mice, Ephx2-/- + CS mice had significantly lower levels of 4HNE and COX2, along with higher FTH1 expression (Figure 5).

-

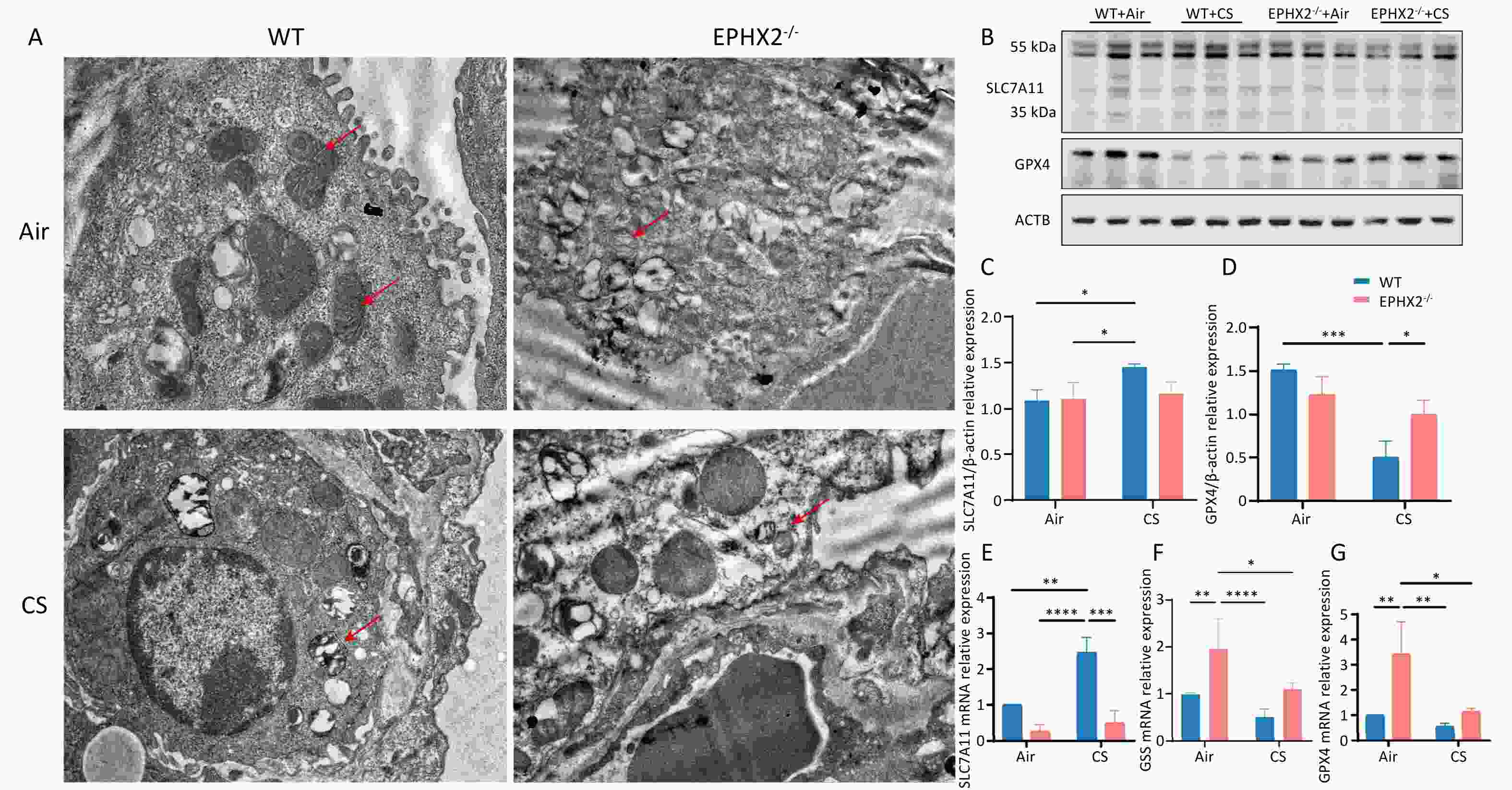

Ferroptosis is pathologically defined by distinctive ultrastructural changes in the mitochondria, including pronounced shrinkage and a notable increase in membrane density[11]. Bronchial epithelial cells from each group were examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). After 16 weeks of CS exposure, the mitochondria of bronchial epithelial cells were smaller, and their membranes were thicker and denser than those of air-exposed mice. These mitochondrial changes were more pronounced in WT mice than in Ephx2-/- mice (Figure 6A).

-

Western blot analysis was performed to decipher the underlying mechanisms by which Ephx2-/- affects ferroptosis. System Xc- activity was assessed by measuring SLC7A11 levels. CS exposure for 16 weeks significantly inhibited the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis; however, this inhibition was markedly milder in Ephx2-/- mice than in WT mice. This conclusion was corroborated by RT-qPCR data (Figure 6B–G). Thus, Ephx2 deficiency may regulate ferroptosis in COPD via this axis.

-

In this study, both WT and Ephx2-/- mice developed severe emphysema and exhibited increased airway resistance, lipid ROS levels, and ferroptosis following exposure to CS for 16 weeks compared with exposure to air. However, these changes were less pronounced in Ephx2-/- mice than in WT mice, accompanied by significantly reduced levels of ferroptosis. The results obtained from immunohistochemical analysis, western blotting, RT-qPCR, and mitochondrial morphological changes visualized by TEM were consistent with these findings. Therefore, knockout of Ephx2 may protect against CS-induced COPD by inhibiting ferroptosis.

Arachidonic acid is one of the most prevalent and widely present polyunsaturated fatty acids in organisms and has important biological functions. It can be metabolized into leukotrienes by lipoxygenases and into prostacyclin by cyclooxygenases. In addition, arachidonic acid can be metabolized to EETs by cytochrome P450 epoxygenase isozymes. EETs are primarily converted to dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids via sEH-mediated hydrolysis, which reduces their biological activity. sEH is encoded by Ephx2 and consists of two domains with different functions. EETs and associated epoxy fatty acids can be converted to the corresponding α,β-diols by sEH catalysis. sEH inhibitors can increase endogenous EETs and have potential therapeutic effects in diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disorders, chronic pain, fibrosis, and neurodegenerative disorders[35].

sEH is widely expressed in the lung tissue and modulates respiratory function under physiological conditions. Importantly, its expression changes in different disease states. Smith et al.[29] reported that after three days of CS exposure, sEH inhibitors partially attenuated inflammation in rats. Wang et al.[28] also found that sEH inhibitors reduced neutrophil accumulation and inflammatory mediator secretion in the BALF of rats with COPD induced by subacute CS exposure, while improving lung function and inhibiting emphysema progression. In our previous study, we demonstrated that EETs inhibited airway inflammation in COPD[29]. In this CS-induced COPD model, inflammatory cytokine level and inflammatory cell count in the BALF, as well as the degree of emphysema, were lower in Ephx2-/- mice than in WT mice. The addition of exogenous EETs inhibited CS-induced secretion of inflammatory cytokines in airway epithelial cells[29,36]. Similarly, our results suggested that Ephx2 deficiency reduced airway resistance, emphysema, and airway epithelial cell death in COPD.

Ferroptosis, a newly identified form of regulated cell death, differs from other cell death mechanisms and plays a role in diverse physiological and pathological processes. During ferroptosis, cell death occurs through long-term accumulation of ROS in cells subjected to erastin treatment. This process can be suppressed using lipophilic antioxidants or iron chelators. Excess iron and ROS have been suggested to induce excessive accumulation of lipid peroxides (LPO), resulting in ferroptosis[11,37]. Ferroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of organ injury and degenerative pathologies, including malignant tumors and neurological disorders[15,17,38]. They are also central to the pathogenesis of acute and chronic pulmonary diseases. Li et al.[19] observed that ferroptosis triggered ALI in mice with intestinal ischemia/reperfusion, a process partially inhibited by the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 (iASPP) via nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2. Ye et al.[39] showed that ferroptosis inducers may act as effective radiosensitizers for malignant tumors, potentially expanding indications and improving radiotherapy efficacy.

Ferroptosis occurs in many cell types after CS exposure. Sampilvanjil et al.[9] suggested that ferroptosis is the dominant contributor to the death of vascular smooth muscle cells after CS exposure. Iron-containing CS particles accumulate in the lungs of smokers and disrupt iron homeostasis. This disruption promotes the inflammatory and oxidative stress responses in COPD[40]. Park et al.[41] identified whole CS condensates as inducers of ferroptosis in bronchial epithelial cells. Yoshida et al.[20] demonstrated that CS exposure promoted labile iron accumulation and enhanced lipid peroxidation, leading to ferroptosis in mouse lung tissue and human bronchial epithelial cells, implicating ferroptosis in COPD pathogenesis. Corroborating these observations, our results showed that 16-week CS exposure significantly reduced GSH and FTH1 levels in mice but significantly increased iron, MDA, 4HNE, COX2, and lipid ROS levels compared with air exposure. These findings suggest that CS exposure may induce ferroptosis in the lung tissue of mice with COPD.

Excessive lipid ROS is a key factor in ferroptosis. In a mouse model of ALI, EETs inhibited cytoplasmic ROS generation in LPS-induced macrophages[31]. Ephx2 regulates sEH expression, thus affecting EET degradation and increasing circulating EET levels. Ephx2-/- mice are therefore a suitable model for investigating EET function in vivo[30]. After 16 weeks of CS exposure, Ephx2-/- mice exhibited significantly reduced lipid ROS and MDA levels compared with WT mice, indicating that EETs inhibit lipid ROS production induced by chronic CS exposure. Collectively, these results indicate that EETs suppress ferroptosis in lung tissue in COPD induced by chronic CS exposure.

This study showed that ferroptosis was increased in the pulmonary tissue of both WT and Ephx2-/- mice exposed to CS for 16 weeks compared with air-exposed controls. Notably, Ephx2-/- + CS mice exhibited lower levels of iron, 4HNE, and COX2 and higher levels of GPX4 than those of WT + CS mice. Ephx2-/- + CS mice also exhibited higher FTH1 levels, although the difference was not significant, which may reflect animal heterogeneity. Thus, ferroptosis increased in the COPD mouse model, and Ephx2 knockout suppressed this process. Recent advances have highlighted diverse mechanisms underlying ferroptosis and its close relationship with metabolic pathways. Lipid metabolic pathways are closely linked to ferroptosis because excessive accumulation of LPO induces cell death. GPX4, a key antioxidant enzyme, reduces phospholipid and cholesterol hydroperoxides to alcohols[42]. Genetic evidence from both cell and animal models has confirmed that GPX4 is a key regulator of ferroptosis[43,44]. GPX4 depletion leads to extensive lipid peroxidation[45], excessive LPO accumulation, and ferroptosis. Our findings suggest that Ephx2 deficiency significantly prevents CS-induced GPX4 reduction in the lung tissue, thereby limiting LPO accumulation and inhibiting ferroptosis in this COPD model.

GSH and GSSG constitute an essential antioxidant defense system, and GSH depletion alone is sufficient to induce ferroptosis. GSH depletion also inactivates GPX4, leading to excessive LPO accumulation and ferroptosis[46]. Our data indicate that GSH levels in WT and Ephx2-/- mice decreased after CS exposure compared with air exposure. Although GSH levels were not significantly different between Ephx2-/- and WT mice, GSSG level after CS exposure warrants attention. The GSH/GSSG ratio did not change significantly in Ephx2-/- mice but decreased in WT mice. These results suggest that Ephx2 deficiency alleviates GSH depletion in COPD lungs exposed to chronic CS. The most upstream component of GSH and GPX4 regulation is system Xc-, which comprises SLC3A2 and SLC7A11[21]. System Xc- exchanges glutamate and cystine across the plasma membrane at a 1:1 ratio. A critical step in GSH synthesis is the reduction of cystine to cysteine. When system Xc- is inhibited, cystine transport decreases, thereby reducing intracellular GSH synthesis and leading to ferroptosis[11]. Our study showed that chronic CS exposure inhibited system Xc- in the lung tissue, as evidenced by the compensatory upregulation of SLC7A11[46]. Ephx2 deficiency mitigated these changes. Thus, Ephx2 deficiency reduces ferroptosis in COPD lung tissue via regulation of the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis.

In summary, we used an Ephx2 knockout mouse model to investigate the role of Ephx2 in COPD induced by chronic CS exposure. Ephx2 deletion reduced emphysema severity and airway resistance compared with WT mice. Ephx2 deficiency also attenuated ferroptosis in COPD lung tissue by alleviating CS-induced inhibition of the system Xc- and via regulation of the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis. These findings suggest that Ephx2 deficiency inhibits ferroptosis in COPD via the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 pathway.

This study has few limitations. The results were derived solely from animal experiments, and some findings were not significant, possibly due to heterogeneity. The system Xc- antiporter is a heterodimer stabilized by its chaperone subunit SLC3A2, which is essential for its function[47,48]. Our study only focused on SLC7A11, a specific substrate-transporting subunit and a key indicator of the system Xc- activity in the context of ferroptosis. We acknowledge that a complete mechanistic understanding requires investigation of both components. Therefore, future work will examine SLC3A2 as a downstream target of Ephx2 deletion to fully elucidate the regulation of the system Xc-.

Furthermore, although our in vivo data strongly support an association between Ephx2 and the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis, this relationship remains correlative. The absence of in vitro data on relevant human cells, such as bronchial epithelial cells or macrophages, limits mechanistic conclusions. In the absence of cellular evidence, it is difficult to distinguish between cell-autonomous and systemic effects. Consequently, extrapolation to human physiology remains tentative. Future studies should define the precise molecular mechanisms linking Ephx2 to the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis in reductionist models and validate these findings in clinical samples, such as lung tissues or sputum from patients with COPD, before positioning Ephx2 as a viable therapeutic target.

Importantly, this is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, to investigate the effect of Ephx2 deficiency on ferroptosis in the lung tissue caused by CS exposure in a COPD mouse model. However, the present study examined only chronic CS exposure in Ephx2-knockout mice. Further investigations are necessary to decipher the precise regulatory mechanisms governing this process.

doi: 10.3967/bes2026.012

Ephx2 Deficiency Suppresses Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease by Inhibiting Ferroptosis Caused by Cigarette Smoke via Regulation of the System Xc-/GSH/GPX4 Axis In Vivo

-

Abstract:

Objective This study investigated the effect of reducing soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH, encoded by the Ephx2 gene) on the mediation of EETs metabolism during ferroptosis in emphysema in vivo. Methods Male C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) and Ephx2-/- mice received whole-body exposure to either cigarette smoke (CS) or air for 16 weeks. The alveolar structure, pulmonary function, lung tissue morphology, cell death, and ferroptosis levels were assessed following exposure. Results CS exposure caused emphysema, reduced pulmonary function, and induced ferroptosis in mice compared with exposure to air. In contrast, following CS exposure, Ephx2-/- mice exhibited significantly lower levels of emphysema, impaired lung function, lung cell death, intracellular iron, lipid reactive oxygen species, cyclooxygenase-2, 4-hydroxynonenal, and malondialdehyde levels than those of WT mice. However, Ephx2-/- mice exhibited higher levels of glutathione and ferritin heavy/chain 1 than those of WT mice. SLC7A11 expression was significantly reduced, whereas glutathione peroxidase 4 expression was markedly increased in Ephx2-/- mice compared with WT mice. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed. Conclusion These results suggest that Ephx2 deficiency inhibits ferroptosis to alleviate CS-induced emphysema, primarily by mitigating its inhibitory effect on the cystine/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 axis. Therefore, Ephx2 represents an effective therapeutic target in CS-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). -

Key words:

- Ephx2 /

- Ferroptosis /

- System Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis /

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease /

- Emphysema

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Beijing Friendship Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China (15-2001).

Conceptualization: Xin He, Haoyan Wang, Bo Xu. Preparation of animal model: Xin He, Ailin Yang, Yue Yu, Bo Wu. Animal experiments: Xin He, Ailin Yang, Yue Yu. Data analysis: Xin He, Ailin Yang. Funding acquisition: Bo Xu, Haoyan Wang, Yanjun Wu, Xin He. Writing–original draft: Xin He, Ailin Yang. Validation: Yue Yu, Ganggang Yu. Methodology: Ganggang Yu. Resources: Ganggang Yu, Bo Wu, Yunxiao Li. Supervision: Bo Xu, Haoyan Wang, Yanjun Wu. Writing–review and editing: Yanjun Wu, Haoyan Wang, Bo Xu. Project administration: Bo Xu, Haoyan Wang, Yanjun Wu. All authors have read and consented to the publication of this manuscript.

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) Funding: 2) Competing Interests: 3) Ethics: 4) Authors’ Contributions: -

Figure 1. Ephx2-/- mice exhibited milder emphysema after chronic stimulation with CS.

A. Representative H&E-stained lung sections of WT and Ephx2-/- mice exposed to CS and air, respectively. Original magnification, ×200. B. Representative genotype of WT and Ephx2-/- mice. The size of the gene product produced by WT and Ephx2-/- mice was 338 bp and 295 bp, respectively. C. The MLI of each group was calculated separately. The MLI of Ephx2-/- + CS mice was significantly reduced compared with that of WT + CS mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. D. The MAN of each group was calculated separately. The MAN of Ephx2-/- + CS was significantly increased compared with that of WT + CS mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 CS, cigarette smoke; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; Ephx2-/-, Ephx2 deficiency; MAN, mean alveolar number; MLI, mean linear intercept; SD, standard deviation; WT, wild-type

Figure 2. Ephx2-/- mice showed less lung function impairment via the ferroptosis signaling pathway following CS exposure.

A–F. Ephx2-/- mice following CS exposure exhibited less impairment of lung function. Rn, Rrs, IC, and tissue damage were determined in WT and Ephx2-/- mice exposed to air and CS. After 16 weeks of exposure to CS, Rrs and Rn were significantly increased, whereas the IC and tissue damage were significantly reduced compared with exposure to air. The Rrs and Rn were significantly lower in Ephx2-/- + CS mice than in WT + CS mice. In addition, the IC and tissue damage in Ephx2-/- + CS mice were higher than that in WT + CS mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. G–J. RNA-seq analysis was conducted in both WT + CS mice and Ephx2-/- + CS mice. A total of 753 DEGs were identified, with 474 upregulated (indicated by red dots) and 279 downregulated (indicated by blue dots) genes. KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the ferroptosis signaling pathway was significantly modulated in Ephx2-/- + CS mice, and GSEA further validated it. CS, cigarette smoke; Ephx2-/-, Ephx2 deficiency; SD, standard deviation; WT, wild-type; RNA-seq, RNA-sequencing; DEG, differentially expressed genes; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

Figure 3. Ephx2-/- mice showed less cell death and lower levels of iron following CS exposure compared with WT mice.

A&B. Cell death in bronchoalveolar epithelium in Ephx2-/- mice was lower than that in WT mice. Detection of TUNEL-positive bronchoalveolar epithelial cells and comparison of their incidence among different groups of mice. Exposure to CS significantly increased the death rate of bronchial epithelial cells in mice. However, Ephx2-/- + CS mice exhibited significantly less cell death than that of WT + CS mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. C–E. After exposure to CS, iron levels in the BALF were significantly increased. This change was significantly inhibited in Ephx2-/- mice compared with that in WT mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group), **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; CS, cigarette smoke; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Ephx2-/-, Ephx2 deficiency; SD, standard deviation; TUNEL, terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling; WT, wild-type

Figure 4. Ephx2-/- mice exhibited lower ROS levels and MDA levels and higher GSH levels following CS exposure.

A&B. After 16 weeks of CS exposure, the levels of lipid ROS in the BALF of each group of mice were determined using flow cytometric analysis. Orange color represents air-exposed WT mice, red color represents air-exposed Ephx2-/- mice, green color represents WT + CS mice, and blue color represents Ephx2-/- + CS mice. The levels of lipid ROS in CS-exposed mice were significantly higher than those in air-exposed mice. Compared with WT + CS mice, Ephx2-/- + CS mice exhibited significantly lower levels of lipid ROS. C&D. Total ROS levels in the BALF of mice were detected by flow cytometry using a DCFH-DA probe. Total ROS levels in CS-exposed mice were significantly higher than those in air-exposed mice. Compared with WT + CS mice, Ephx2-/- + CS mice showed significantly lower levels of total ROS. E–H. After 16 weeks of CS exposure, BALF from each group of mice was collected for analysis. The levels of GSH and SOD in the BALF of mice exposed to CS were significantly lower than those in air-exposed mice. Moreover, MDA levels in the BALF of WT mice exposed to CS were significantly higher than those in air-exposed mice. Compared with WT + CS mice, SOD levels in the BALF of Ephx2-/- + CS mice were significantly higher, whereas those of MDA in Ephx2-/- + CS mice were significantly lower. GSH levels in the BALF of Ephx2-/- + CS mice were higher, while GSSG levels in the BALF of Ephx2-/-+CS mice were lower than those in WT + CS mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. I. DCFH-DA probe was used to determine the total ROS levels in the lung tissue. ROS levels were significantly increased in the airways of WT + CS mice. Compared with WT + CS mice, ROS levels were lower in the airways of Ephx2-/- + CS mice. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; CS, cigarette smoke; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; Ephx2-/-, Ephx2 deficiency; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SD, standard deviation; SOD, superoxide dismutase; WT, wild-type

Figure 5. Ephx2-/- mice exhibited lower 4HNE and COX2 levels and higher FTH1 expression following CS exposure compared with WT mice.

After 16 weeks of CS exposure, the levels of 4HNE, COX2, and FTH1 in the lung tissues of mice from each group were determined. A. Western blot assay results showed that the levels of 4HNE and COX2 were significantly increased, whereas those of FTH1 were significantly decreased after 16 weeks of CS exposure compared with those of air exposure. After exposure to CS, Ephx2-/- mice had lower levels of 4HNE, significantly lower levels of COX2, and higher levels of FTH1 than those of WT mice. Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. B. The expression of 4HNE and COX2 in the lung tissues of mice was observed using fluorescence microscopy. Green color represents 4HNE, and red color represents COX2. Compared with the air-exposed group, the levels of 4HNE and COX2 were significantly increased in the CS-exposed group. After exposure to CS, Ephx2-/- mice exhibited significantly lower levels of 4HNE and COX2 than those of WT mice. CS, cigarette smoke; COX2, cyclooxygenase 2; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DCFH-DA, 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; FTH1, ferritin heavy/chain 1; GSH, glutathione; 4HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; Ephx2-/-, Ephx2 deficiency; PTGS2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase; SD, standard deviation; WT, wild-type

Figure 6. Ephx2 deletion inhibits ferroptosis via upregulation of the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis.

A. The mitochondrial morphology of in bronchial epithelial cells was altered in CS-exposed mice compared with air-exposed mice, mainly manifested as thickening of the mitochondrial membrane. This change was observed in both CS-exposed groups but was more pronounced in the WT group. The red arrow indicates mitochondria. B–D. Western blot assay results showed that SLC7A11 levels were higher and GPX4 levels were lower in CS-exposed mice than in air-exposed mice. After exposure to CS, Ephx2-/- mice exhibited lower levels of SLC7A11 and significantly higher levels of GPX4 than those of WT mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group), *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. E–G. RT-qPCR assay showed that SLC7A11 levels were significantly higher and GSS and GPX4 levels were lower in CS-exposed mice than in air-exposed mice. After exposure to CS, Ephx2-/- mice exhibited significantly lower levels of SLC7A11 and higher levels of GSS and GPX4 than those of WT mice. Data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 6 mice per group), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. CS, cigarette smoke; GPX4, glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, glutathione; SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7 member 11; GSS, glutamine synthetase; WT, wild-type; Xc-, system cystine

-

[1] Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD (2025 REPORT). https://goldcopd.org. [2] Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 2012; 380, 2095−128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [3] Burney P, Kato B, Janson C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality and prevalence: the associations with smoking and poverty: a BOLD analysis—authors' reply. Thorax, 2014; 69, 869−70. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205474 [4] Januszek R, Siudak Z, Dziewierz A, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affects the angiographic presentation and outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease treated with percutaneous coronary interventions. Pol Arch Intern Med, 2018; 128, 24−34. doi: 10.20452/pamw.4145 [5] Franssen FME, Soriano JB, Roche N, et al. Lung function abnormalities in smokers with ischemic heart disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2016; 194, 568−76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2480OC [6] Finks SW, Rumbak MJ, Self TH. Treating hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med, 2020; 382, 353−63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1805377 [7] Cazzola M, Rogliani P, Calzetta L, et al. Targeting mechanisms linking COPD to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2017; 38, 940−51. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.07.003 [8] Mouronte-Roibás C, Leiro-Fernández V, Fernández-Villar A, et al. COPD, emphysema and the onset of lung cancer. A systematic review. Cancer Lett, 2016; 382, 240−4. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.002 [9] Sampilvanjil A, Karasawa T, Yamada N, et al. Cigarette smoke extract induces ferroptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2020; 318, H508−18. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00559.2019 [10] Heijink IH, de Bruin HG, Dennebos R, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced epithelial expression of WNT-5B: implications for COPD. Eur Respir J, 2016; 48, 504−15. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01541-2015 [11] Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell, 2012; 149, 1060−72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 [12] Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol, 2016; 26, 165−76. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.014 [13] Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife, 2014; 3, e02523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02523 [14] Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, et al. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2016; 113, E4966−75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603244113 [15] Mi YJ, Gao XC, Xu H, et al. The emerging roles of ferroptosis in Huntington's disease. Neuromolecular Med, 2019; 21, 110−9. doi: 10.1007/s12017-018-8518-6 [16] Wang H, An P, Xie EJ, et al. Characterization of ferroptosis in murine models of hemochromatosis. Hepatology, 2017; 66, 449−65. doi: 10.1002/hep.29117 [17] Shen ZY, Song JB, Yung BC, et al. Emerging strategies of cancer therapy based on ferroptosis. Adv Mater, 2018; 30, 1704007. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704007 [18] Li X, Duan LJ, Yuan SJ, et al. Ferroptosis inhibitor alleviates radiation-induced lung fibrosis (RILF) via down-regulation of TGF-β1. J Inflamm, 2019; 16, 11. doi: 10.1186/s12950-019-0216-0 [19] Li YC, Cao YM, Xiao J, et al. Inhibitor of apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 inhibits ferroptosis and alleviates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury. Cell Death Differ, 2020; 27, 2635−50. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-0528-x [20] Yoshida M, Minagawa S, Araya J, et al. Involvement of cigarette smoke-induced epithelial cell ferroptosis in COPD pathogenesis. Nat Commun, 2019; 10, 3145. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10991-7 [21] Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T, et al. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J Biol Chem, 1999; 274, 11455−8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11455 [22] La Bella V, Valentino F, Piccoli T, et al. Expression and developmental regulation of the cystine/glutamate exchanger (Xc-) in the rat. Neurochem Res, 2007; 32, 1081−90. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9277-6 [23] Spector AA, Fang X, Snyder GD, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs): metabolism and biochemical function. Prog Lipid Res, 2004; 43, 55−90. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00049-3 [24] Wagner KM, McReynolds CB, Schmidt WK, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for pain, inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther, 2017; 180, 62−76. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.06.006 [25] Smith KR, Pinkerton KE, Watanabe T, et al. Attenuation of tobacco smoke-induced lung inflammation by treatment with a soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2005; 102, 2186−91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409591102 [26] Hu SQ, Luo JL, Fu ML, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase deletion attenuated nicotine-induced arterial stiffness via limiting the loss of SIRT1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2021; 321, H353−68. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00979.2020 [27] Luo XQ, Duan JX, Yang HH, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids inhibit the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in murine macrophages. J Cell Physiol, 2020; 235, 9910−21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29806 [28] Wang L, Yang J, Guo L, et al. Use of a soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor in smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2012; 46, 614−22. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0359OC [29] Li YX, Yu GG, Yuan SP, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation and autophagy are attenuated in Ephx2-deficient mice. Inflammation, 2017; 40, 497−510. doi: 10.1007/s10753-016-0495-z [30] Sinal CJ, Miyata M, Tohkin M, et al. Targeted disruption of soluble epoxide hydrolase reveals a role in blood pressure regulation. J Biol Chem, 2000; 275, 40504−10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008106200 [31] Crowley G, Kwon S, Caraher EJ, et al. Quantitative lung morphology: Semi-automated measurement of mean linear intercept. BMC Pulm Med, 2019; 19, 206. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0915-6 [32] Meng LY, Tao WF, Li J, et al. Effects of bisphenol A and its substitute, bisphenol F, on the gut microbiota in mice. Biomed Environ Sci, 2024; 37, 19−30. [33] Alves CE, Santos TG, Vitoretti LB, et al. Effect of photobiomodulation therapy in an experimental model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a dosimetric study. Allergies, 2025; 5, 33. doi: 10.3390/allergies5040033 [34] Janssen R, Piscaer I, Franssen FME, et al. Emphysema: looking beyond alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Expert Rev Respir Med, 2019; 13, 381−97. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2019.1580575 [35] Harris TR, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase: gene structure, expression and deletion. Gene, 2013; 526, 61−74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.008 [36] Li YX, Yu GG, Yuan SP, et al. 14, 15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid suppresses cigarette smoke condensate-induced inflammation in lung epithelial cells by inhibiting autophagy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2016; 311, L970−80. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00161.2016 [37] Yagoda N, von Rechenberg M, Zaganjor E, et al. RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature, 2007; 447, 865−9. doi: 10.1038/nature05859 [38] Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol, 2017; 13, 91−8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2239 [39] Ye LF, Chaudhary KR, Zandkarimi F, et al. Radiation-induced lipid peroxidation triggers ferroptosis and synergizes with ferroptosis inducers. ACS Chem Biol, 2020; 15, 469−84. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00939 [40] Ghio AJ, Hilborn ED, Stonehuerner JG, et al. Particulate matter in cigarette smoke alters iron homeostasis to produce a biological effect. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008; 178, 1130−8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-334OC [41] Park EJ, Park YJ, Lee SJ, et al. Whole cigarette smoke condensates induce ferroptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells. Toxicol Lett, 2019; 303, 55−66. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.12.007 [42] Jiang XJ, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2021; 22, 266−82. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8 [43] Seibt TM, Proneth B, Conrad M. Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radic Biol Med, 2019; 133, 144−52. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.014 [44] Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell, 2014; 156, 317−31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010 [45] Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab, 2008; 8, 237−48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005 [46] Lo M, Ling V, Wang YZ, et al. The xc- cystine/glutamate antiporter: a mediator of pancreatic cancer growth with a role in drug resistance. Br J Cancer, 2008; 99, 464−72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604485 [47] Xiang P, Chen QQ, Chen L, et al. Metabolite Neu5Ac triggers SLC3A2 degradation promoting vascular endothelial ferroptosis and aggravates atherosclerosis progression in ApoE-/- mice. Theranostics, 2023; 13, 4993−5016. doi: 10.7150/thno.87968 [48] Zheng YQ, Zhou SL, Tao YR, et al. Elevated SLC3A2 expression promotes the progression of gliomas and enhances ferroptosis resistance through the AKT/NRF2/GPX4 axis. Cancer Res Treat, 2025; 10. (查阅网上资料, 未找到本条文献卷号和页码, 请确认) -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links