-

Silicosis is a chronic progressive occupational lung disease primarily characterized by extensive nodular fibrosis in the lungs, resulting from long-term inhalation of significant amounts of crystalline silica (SiO2) dust[1,2]. The structure and function of lung tissue in patients with silicosis are impaired to varying degrees. In severe cases, it can lead to the loss of occupational capacity and even progress to pulmonary heart disease, cardiac failure, and respiratory failure[3,4]. Damage to alveolar epithelial cells, lung tissue remodeling, fibrosis, and the underlying mechanisms induced by SiO2 have been the focus of occupational disease research worldwide[5]. However, the effects of SiO2 exposure on other organs such as the heart, liver, kidneys, and brain have not been extensively investigated. Clinical examinations have shown that patients with silicosis often exhibit impaired right ventricular contractile function, elevated pulmonary arterial pressure, reduced respiratory function, worsening disease severity, and eventually heart failure[6,7].

Nanosized SiO2 has attracted more attention regarding its detrimental effects on the body compared to conventional microsized SiO2[8-10]. Research has shown that nanosized SiO2 deposition in organs such as the lungs, liver, cardiovascular system, kidneys, and testes can lead to cellular membrane damage, oxidative stress, inflammation, and genetic toxicity[11-13]. In contrast, microsized SiO2 can barely enter the bloodstream directly through the alveolar and capillary walls, potentially causing indirect damage to other organs, such as changes in peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations, immunoglobulins, oxidative stress markers, and inflammatory mediators[14,15]. Patients with silicosis and animal models have shown increased blood iron levels and the abnormal expression of iron-related transport proteins, suggesting SiO2 affects body iron metabolism[16,17]. Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent cell death process characterized by lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, is involved in various diseases[18]. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), also known as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), are recognized markers of ferroptosis[19]. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor that responds to oxidative and electrophilic stress, regulates several iron metabolism genes[20,21]. Studies have shown that ferroptosis is involved in the development of lung fibrosis in SiO2-induced silicosis mouse models[17,22,23]. However, it is unclear whether conventional microsized SiO2 causes abnormal iron metabolism in the blood and organs, thereby inducing ferroptosis. Therefore, this study aimed to examine myocardial ferroptosis in a silicosis mouse model and provide insights into the mechanisms underlying SiO2-induced myocardial damage.

-

Crystalline silica particles (particle size 1–5 μm, purity > 99.5%) were provided by U.S. Silica Company (Frederick, MD, USA). Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) (≥ 95%, HPLC) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and deferoxamine (DFO) was purchased from Medchem Express (Shanghai, China). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and iron stain assay kits were obtained from Solarbio Science and Technology Corp. (Beijing, China). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and mouse aspartate aminotransferase (AST) assay kits were purchased from Jiancheng Corp. (Nanjing, China). A Prussian blue staining kit was purchased from Solarbio Science and Technology Corp. (Beijing, China). Primary antibodies against glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) (1:1,000 for western blot), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) (1:1,000 for western blot), heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) (1:1,000 for western blot), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) (1:1,000 for western blot), xCT (1:1,000 for western blot), and β-actin (1:1,000 for western blot) as well as the secondary antibody used for immunoblotting were purchased from Affinity Biosciences (Jiangsu, China). Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) (1:1,000 for western blot) was obtained from Proteintech Group (Wuhan, China). The iron colorimetric assay kit was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies (Tokyo, Japan).

-

SPF male C57BL/6 mice (18–20 g, 6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). After acclimating for 1 week , the mice were randomly divided into four experimental groups (n = 8 per group). A silicosis mouse model was established by intratracheal instillation of SiO2 (dissolved in sterile saline) at a dose of 50 μL (50 mg/mL) as previously described[23]. Sterile saline was administered to the control group via intratracheal instillation. Twenty-eight days after SiO2 administration, eight mice in the SiO2 group were administered Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) (1 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injections (SiO2 + Fer-1 group) and an additional eight mice were administered deferoxamine (DFO) (20 mg/kg) every 2 d (SiO2 + DFO group). This regimen was maintained up to the 56th day, after which the treatment was discontinued. The animals were euthanized for tissue collection on the 84th day after initial SiO2 administration[24-26], and blood and tissue samples were collected for subsequent experiments. All animal procedures complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the North China University of Science and Technology and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of North China University of Science and Technology (Protocol No. 2023-SY-014).

-

The level of serum creatine kinase isoenzymes (CK) was measured using an automatic biochemical analyzer (ADVIA® 2400, Siemens Ltd., China). The enzyme activities of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in the serum were detected using quick, sensitive, and convenient assay kits according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

-

Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations were quantified using a Lipid Peroxidation MDA Assay Kit (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China). This method utilizes the interaction between MDA and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to measure absorbance at 532 nm. The MDA values were determined using a standard curve derived from the reference standards of the kit under identical conditions. Commercial assay kits (Solarbio, Beijing, China) were used to measure SOD concentrations. This assay relies on SOD’s ability to eliminate O2−, which in turn reduces nitrogen blue tetrazolium, forming a blue-colored methanogen. The SOD activity was assessed based on the absorbance of blue methanogens at 560 nm.

-

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Prussian blue staining were performed as previously described[27]. Briefly, after overnight fixation in 4% formaldehyde, murine hearts were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm sections. Cardiac tissues were transversely sectioned from the middle segment and stained with H&E. For Prussian blue staining, cardiac sections were deparaffinized at 60 °C for 1 h and hydrated in distilled water. Equal volumes of potassium ferrocyanide and hydrochloric acid were mixed to prepare a working iron stain solution. The cardiac tissues were then incubated in the working solution for 3 min. The samples were viewed under a light microscope (Olympus, Japan).

-

Fresh myocardium samples (1 mm3) were quickly and carefully collected from the left ventricle of the mice and placed in pre-labeled tubes containing glutaraldehyde fixative solution for 4 h. Cardiac tissues were then subjected to permeation, dehydration, and overnight embedding. Samples were viewed using a transmission electron microscope (HITACHI, Japan).

-

Blood samples were collected and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm (4 °C) for 15 min to obtain serum. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm, and the non-heme iron content of unknowns was calculated by drawing a standard curve, the results of which are presented in milligrams of iron per deciliter of serum. Non-heme iron levels in cardiac tissues were detected using the chromogen method, as described previously[27], and the results are presented in micrograms of iron per gram of cardiac tissue.

-

Quantitative real-time PCR and western blotting were performed as previously described[23]. The mRNA and protein expression levels of target genes were normalized to β-actin. The primer sequences used for the qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primer used for qRT-PCR

qPCR Primers Sequence 5’–3’ GPX4 F CGAGCTCGTGTGTGGCTGTTCCCCAGG GPX4 R CCAAGCTTCAGGAAGCAACATTTACTTG PTGS2 F TGCTGTTCCAACCCATGTCA PTGS2 R TGTCAGAAACTCAGGCGTAGT Nrf2 F TGAAGCTCAGCTCGCATTGA Nrf2 R TGCTCCAGCTCGACAATGTT HO-1 F TGCTAGCCTGGTGCAAGATACT HO-1 R AGGCCACATTGGACAGAGTT xCT F TGCAATCAAGCTCGTGAC xCT R AGCTGTATAACTCCAGGGACTA NQO1 F GCTGCCATGTACGACAACGG NQO1 R ATGCCACTCTGAATCGGCCA β-actin F TGGGACGATATGGAGAAGAT β-actin R ATTGCCGATAGTGATGACCT -

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23.0) software. Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparisons among multiple groups were analyzed via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test, whereas comparisons between two groups were evaluated using Student’s t-test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

Although extensive research exists on lung injuries caused by SiO2, reports on myocardial tissue damage induced by SiO2 are relatively scarce.

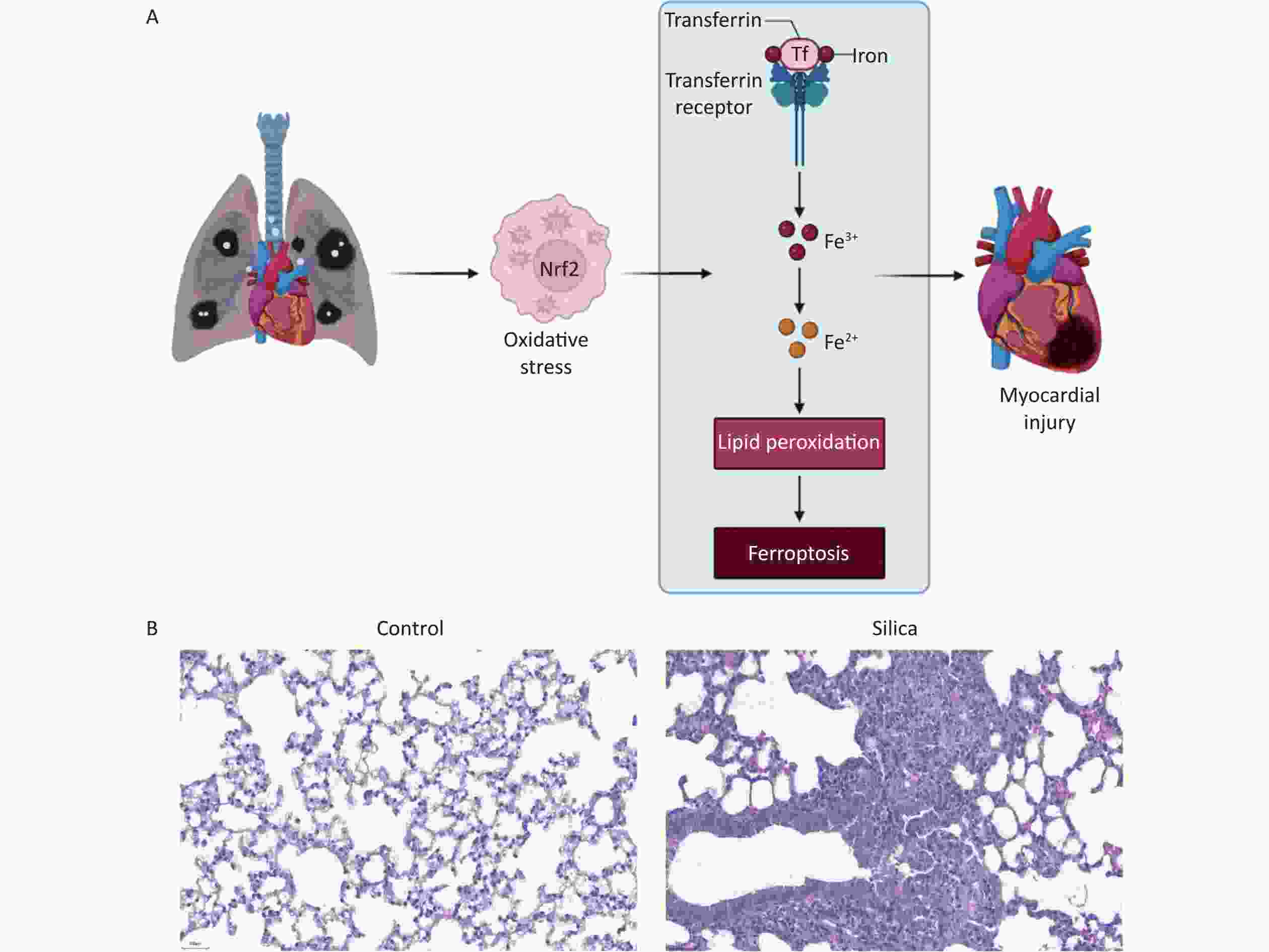

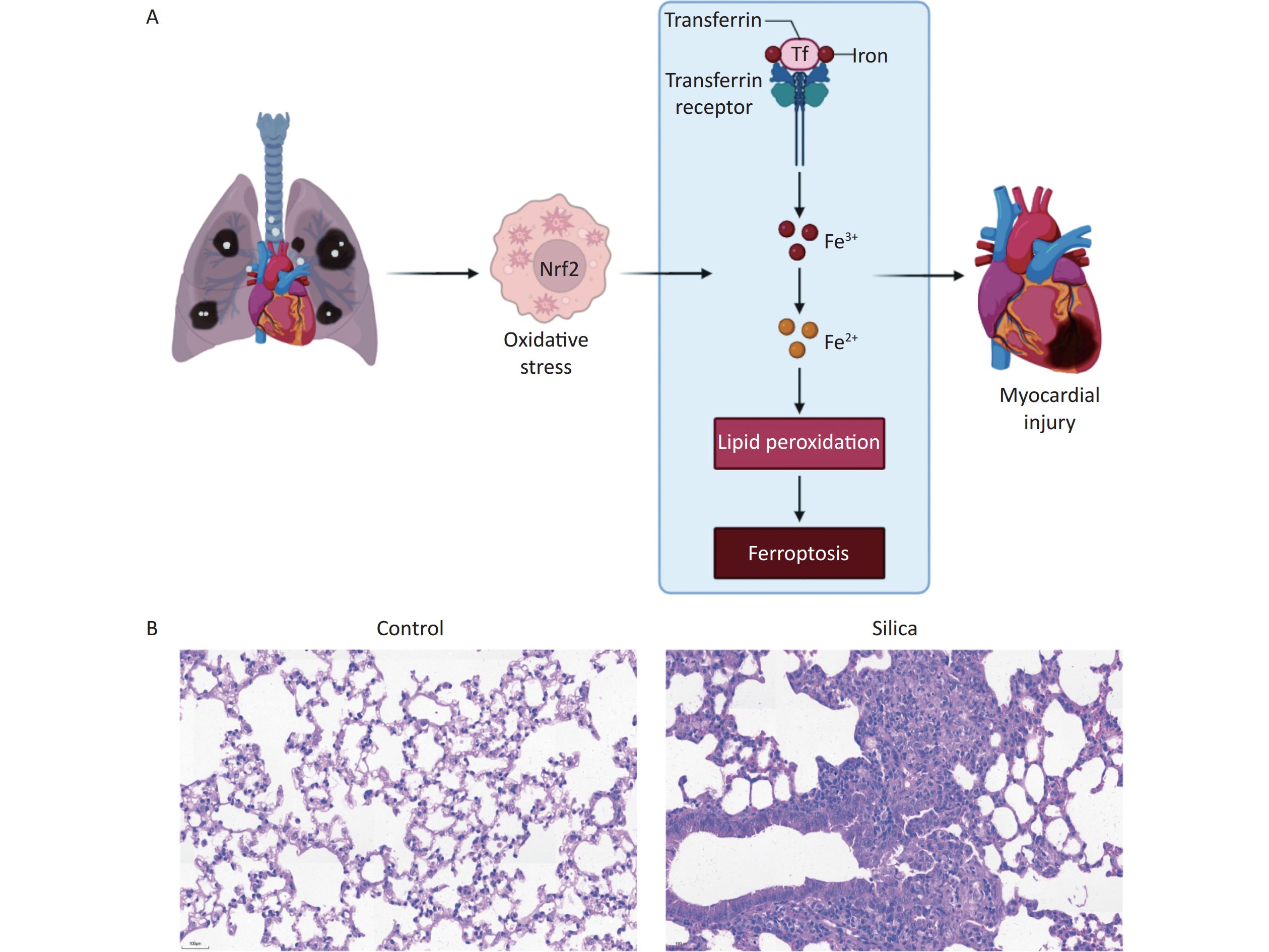

In the present study, we developed a silicosis mouse model and observed fibrotic nodules in the lung tissues of the mice in the 84-day model group. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in the control group, as presented in the scientific hypothesis diagram (Figure 1A) and Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of lung tissue from mice with silicosis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Establishing an silicosis mouse model after exposure to SiO2 for 84 d. (A) Scientific hypothesis diagram. (B) Lung tissue of control mice and mice with silicosis. H&E staining (200× magnification, n = 3).

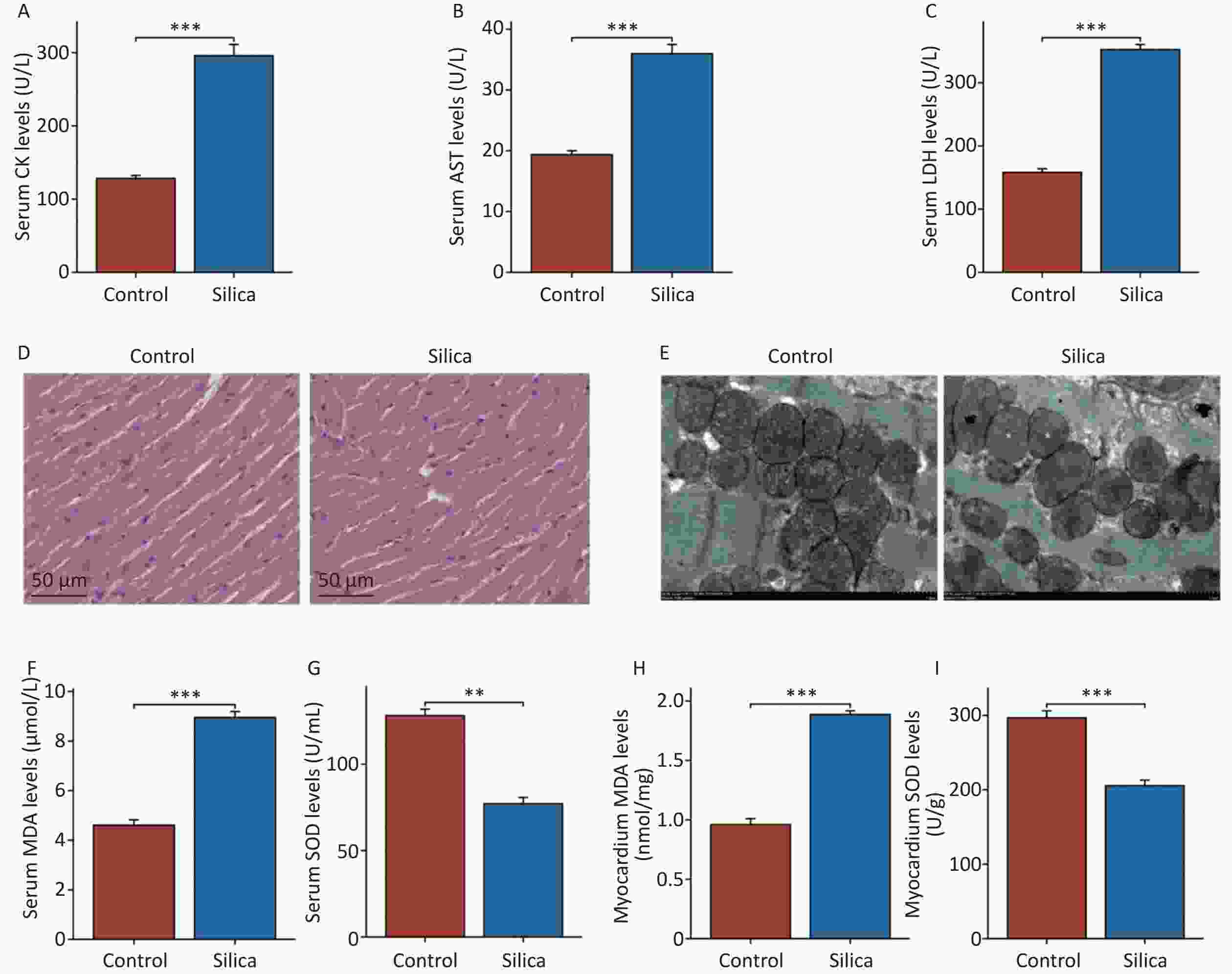

In the present study, we observed found myocardial damage in silicotic mice after 84 d of exposure to SiO2. We found significant increases in the levels of biochemical indicators CK, AST, and LDH in the serum of the model group compared to those in the control group (Figure 2A–C). However, no significant histopathological changes were observed upon examination with H&E staining under an optical microscope (Figure 2D). Compared to the control group, the cardiomyocytes in the model group exhibited disorganized mitochondrial arrangement, mitochondrial shrinkage, and disappearance of cristae (Figure 2E). Subsequently, we examined oxidative damage-related markers in the serum and myocardial tissues of the mice. The results showed increased levels of MDA and decreased levels of SOD in the serum and myocardium of the model group compared with those in the control group (Figure 2F–I). Although no pathological changes were observed in the myocardial tissue of SiO2-exposed mice, mitochondrial organelles were damaged, indicating potential injury to the myocardium. This may be associated with SiO2-induced myocardial oxidative stress, either directly or indirectly.

Figure 2. Myocardial damage in mice injected with SiO2 (50 mg/mL) after 84 d. (A–C) Creatine kinase isoenzymes (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in serum (n = 6). (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for cardiac tissues histopathology (n = 3). (E) Transmission electron micrograph of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes (the yellow asterisks indicate the disappearance of mitochondrial cristae). (F–G) The serum and cardiac malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in indicated groups (n = 6). (H–I) The serum and cardiac superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels in indicated groups (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

-

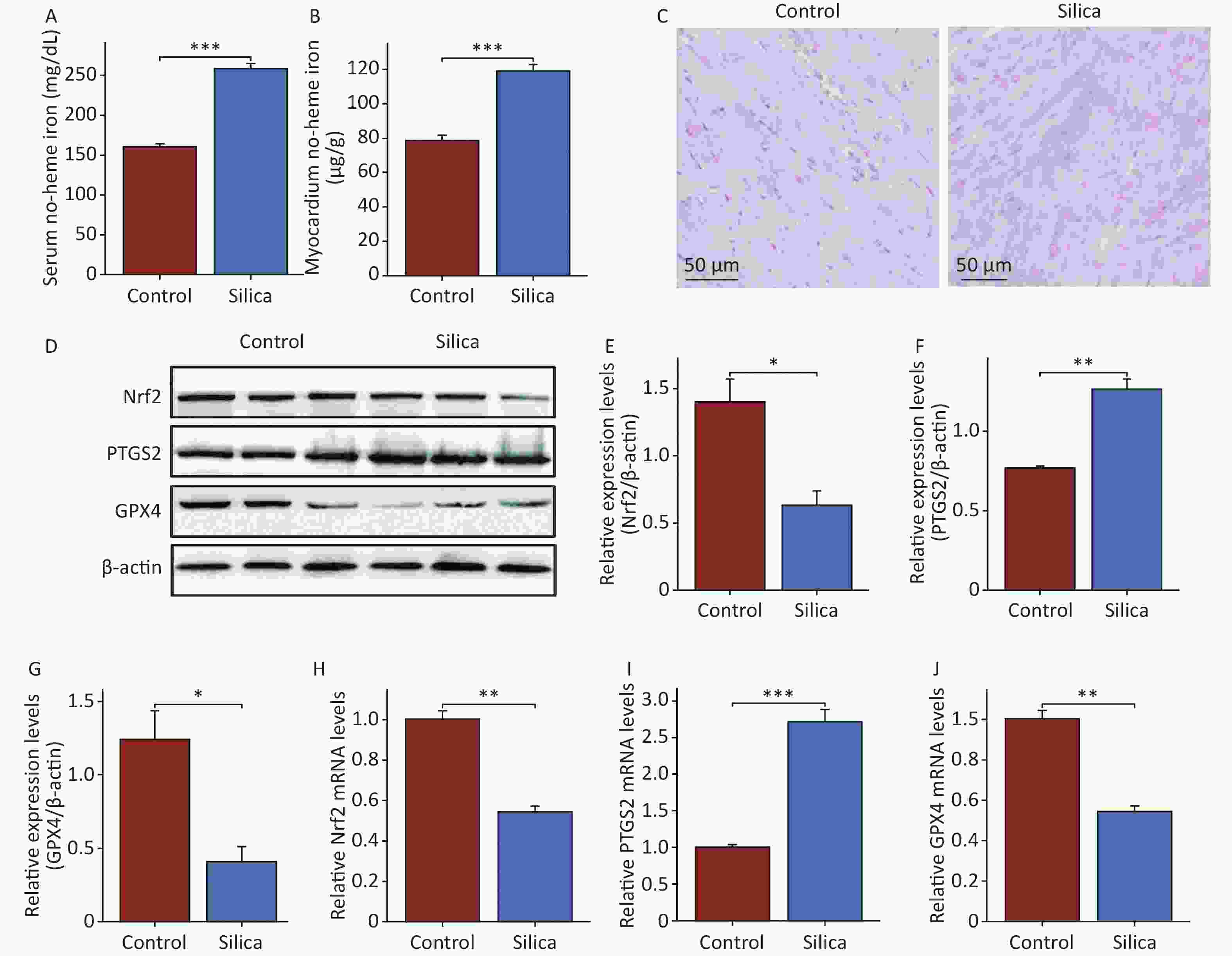

To further investigate the effects and mechanisms of SiO2 on the myocardial tissue, we examined the iron content in the serum and myocardial tissue. The results showed that non-heme iron levels in both the serum and myocardium of SiO2-exposed mice were higher than those in the control group (Figure 3A and B). Prussian blue staining also revealed iron deposition in the myocardial tissues of SiO2-exposed mice (Figure 3C). We then examined the ferroptosis markers GPX4 and PTGS2 (Figure 3D–F, H, and I). The results showed that both mRNA and protein expression of GPX4 were lower, whereas the mRNA and protein expression of PTGS2 were higher in the myocardial tissue of SiO2-exposed mice than in the control group. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy revealed a disordered arrangement, swelling, and loss of mitochondria in the myocardial cells of SiO2-exposed mice (Figure 2E). These results suggest that ferroptosis is activated in the cardiac tissues of SiO2-exposed mice.

Figure 3. Ferroptosis in cardiac tissue is activated in mice injected with SiO2. (A–B) The serum and cardiac non-heme iron in the control and model groups (n = 6). (C) Prussian blue staining for iron (n = 3). (D–J) The protein (n = 3) and mRNA levels of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) in myocardial tissues of each group (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

-

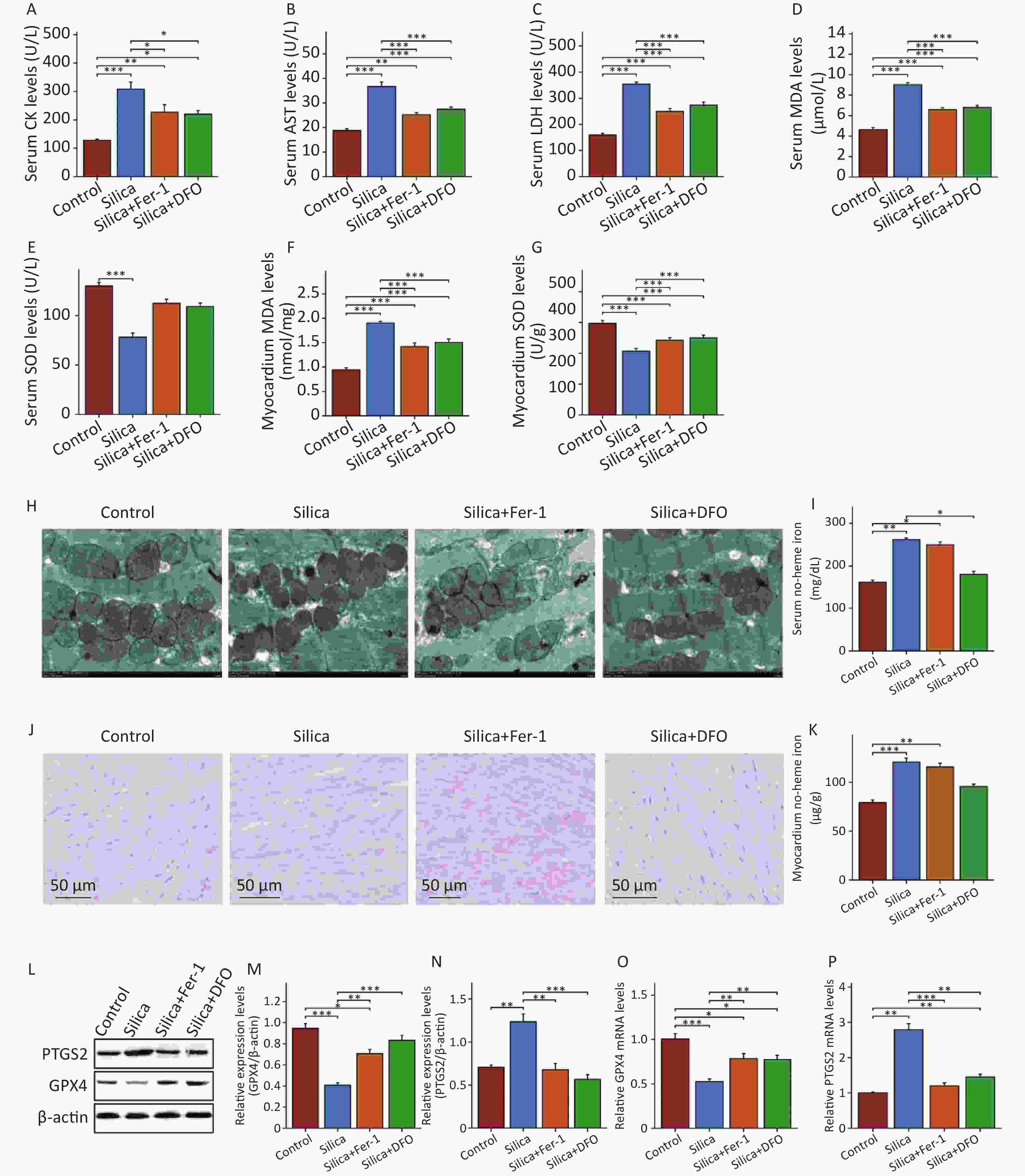

We administered Fer-1 and DFO in SiO2-exposed mice. Fer-1 inhibits iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, whereas DFO is an iron chelator that is widely used to reduce iron accumulation and deposition in tissues. Following Fer-1 and DFO intervention, there was a significant decrease in the levels of CK, LDH, and AST in the serum compared to SiO2-exposed mice (Figure 4A–C), as well as decreased MDA levels and increased SOD activity in the serum and myocardial tissues (Figure 4D–G). Electron microscopy showed that both Fer-1 and DFO improved the disordered arrangement and swelling of mitochondria in SiO2-induced mouse myocardium (Figure 4H). Fer-1 intervention did not improve myocardial iron deposition in SiO2-exposed mice, whereas DFO significantly reduced non-heme iron levels in the peripheral blood and myocardium of SiO2-exposed mice (Figure 4I–K). Furthermore, both ferroptosis inhibitors significantly decreased PTGS2 protein and mRNA expression levels and increased GPX4 protein and mRNA expression levels in the myocardium (Figure 4L–P). These results demonstrate that DFO and Fer-1 have protective effects against ferroptosis in SiO2-induced mouse myocardial cells.

Figure 4. Inhibition of ferroptosis significantly reduces heart damage in mice injected with SiO2. (A–C) The levels of CK, AST and LDH in serum (n = 6). (D–G) The serum and cardiac MDA and SOD levels (n = 6). (H) Transmission electron micrograph of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes (n = 3). (I–J) The serum and cardiac non-heme iron (n = 3). (K) Prussian blue staining for iron (n = 3). (L–P) The protein (n = 3) and mRNA levels of GPX4 and PTGS2 in myocardial tissues of each group (n = 6). *Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

-

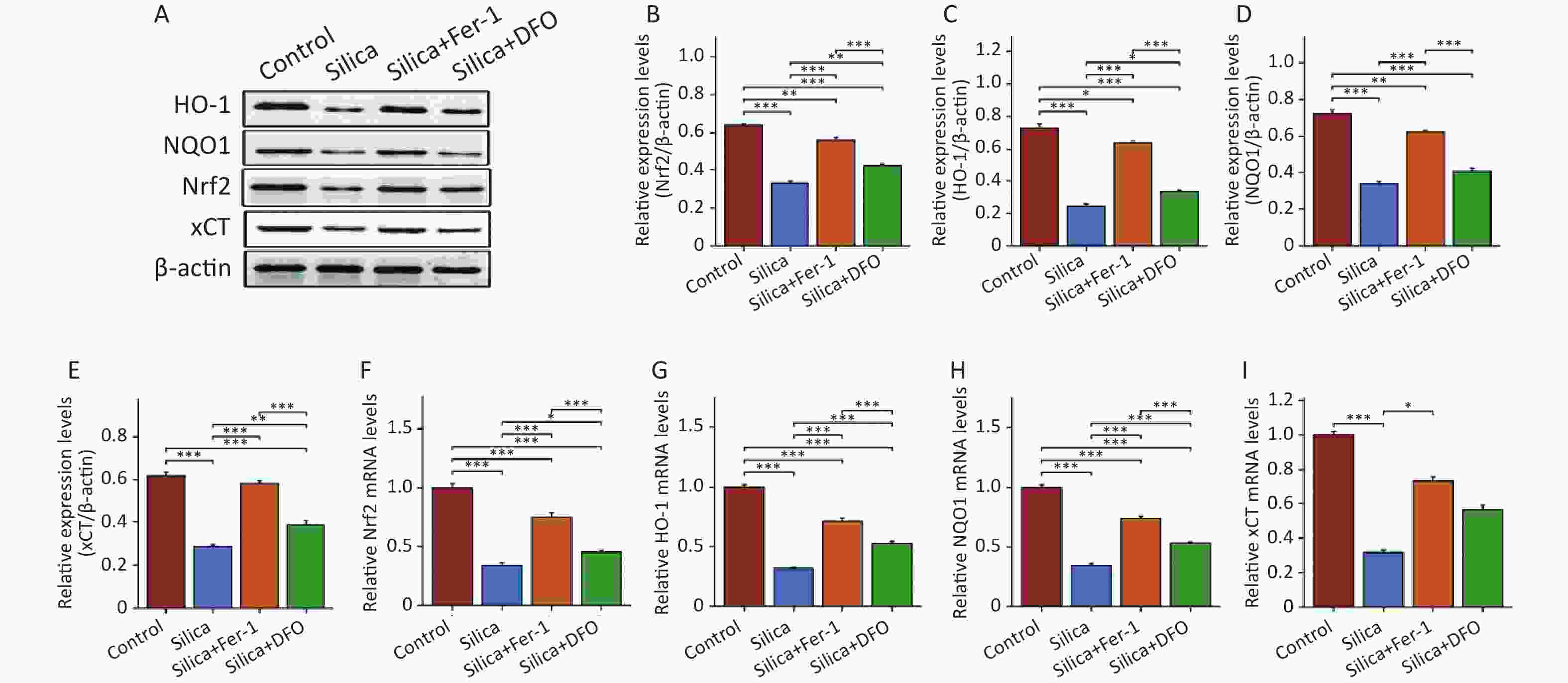

This study further evaluated the changes in Nrf2 and its downstream proteins in the myocardium of SiO2-exposed mice following intervention with ferroptosis inhibitors. The results showed that compared to the control group, the expression of Nrf2 and its downstream proteins HO-1, NQO1, and xCT decreased in the myocardial tissue of SiO2-exposed mice (Figure 5A–E), as well as the mRNA expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 (Figure 5F–I). Interestingly, although both Fer-1 and DFO increased the mRNA and protein expression of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, and xCT in the myocardium of SiO2-exposed mice, there were still differences in Nrf2 expression between the control and SiO2 groups. Compared with the DFO intervention group, Fer-1 intervention was better able to activate the expression of Nrf2 and its downstream proteins in the myocardium of SiO2-exposed mice.

Figure 5. The protein and mRNA expression of Nrf2, heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), and xCT in mice injected with SiO2 with or without ferroptosis inhibitor intervention. (A–E) The protein levels of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, and xCT in myocardial tissues (n = 3). (F–I) The mRNA levels of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, and xCT in myocardial tissues (n = 6). *Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

-

In a SiO2-induced mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis, we observed significant changes in serum biomarkers (such as CK and AST) associated with myocardial injury. We then attempted to observe the extent of myocardial damage in SiO2-exposed mice, but no significant pathological changes in the myocardial tissue were found 84 d after establishing silicosis mouse models. However, interestingly, upon observing the ultrastructure, we noticed that the mitochondria in the myocardial cells were swollen with disappearing cristae. In this study, we provided explanations for myocardial injury in SiO2-exposed mice from the perspective of iron-dependent cell death and identified potential preventive targets for clinical manifestations such as pulmonary heart disease and late-stage heart failure in patients with silicosis.

In clinical practice, there is a time lag between the occurrence of cardiac symptoms (e.g., acute myocardial infarction) and eventual mortality in populations occupationally exposed to SiO2[28,29]. Therefore, the effects of SiO2 on the myocardium are generally observed during the late stages of silicosis[30,31]. Although some reports have shown an increased risk of coronary artery disease mortality in individuals occupationally exposed to SiO2, valid measures of the cause of mortality are lacking, with endpoint definitions not distinguishing between first-time and recurrent events and obscuring the onset time. This overlooked the effect of SiO2 on myocardial injury[32,33]. Our results showed significant changes in peripheral blood biomarkers associated with the myocardium (CK, AST, and LDH). This is consistent with studies that reported changes in myocardial injury biomarkers in rats exposed to nanosized SiO2[31,34]. Furthermore, the observation of myocardial cell morphological damage after SiO2 exposure showed significant mitochondrial structural effects. Mitochondria are the main energy source and play an important role in maintaining normal cellular physiology; however, they are prone to damage under adverse environmental factors, leading to dysfunction, cellular impairment, and adverse reactions such as autophagy, apoptosis, and necrosis, negatively affecting organismal health[35]. Recent studies have reported that SiO2 treatment of rat myocardial cells causes mitochondrial membrane depolarization and a 55% decrease in ATP production, along with glutathione depletion and hydrogen peroxide production, suggesting that SiO2 increases oxidative stress and impairs mitochondrial function and energy supply[14,36]. Once particulate matter enters the bloodstream through the blood-gas barrier, ultrafine particles may affect myocardial cells, causing ischemia or heart failure[37]. However, current research on the effects of conventional SiO2 particle on myocardial cells is limited to SiO2-induced pulmonary inflammation, which leads to systemic inflammation[38]. We showed that SiO2 exposure increased the blood non-heme iron content and myocardial accumulation, causing iron-dependent myocardial cell death, providing new insights into conventional SiO2-induced myocardial injury mechanisms.

Ferroptosis is a form of regulated cell death characterized by iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation[39]. Recent studies have shown that iron plays an important regulatory role in diseases such as myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, cardiomyopathy, and heart failure[40,41]. Iron overload-induced myocardial damage is known as iron overload cardiomyopathy, in which free intracellular iron enters the mitochondria, generates ROS, and causes oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation[42]. We found that SiO2 exposure in mice increased cardiac iron levels and altered the expression of ferroptosis markers GPX4 and PTGS2. Intervention with Fer-1 or DFO in SiO2-exposed mice showed that DFO reduced peripheral and cardiac iron levels and Fer-1 inhibited lipid peroxidation, which alleviated SiO2-induced cardiac damage, and restored mitochondrial morphology and cardiac injury serum biomarkers. Similarly, the inhibition of ferroptosis in cardiac diseases such as hemochromatosis and ischemic heart disease can alleviate disease progression[43,44]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that certain natural compounds such as resveratrol and salidroside, can alleviate cardiac injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. However, the mechanisms underlying these effects are not yet fully understood[45,46]. Therefore, mitigating SiO2-induced cardiac toxicity by regulating the iron concentration could provide preventative and treatment strategies.

Ferroptosis is characterized by iron accumulation, increased lipid peroxidation, and inability to reduce lipid peroxides. Many ferroptosis cascade components are Nrf2 target genes, indicating their critical mediating roles[20,47]. We found changes in Nrf2 pathway expression in SiO2-exposed cardiac tissues. DFO intervention to reduce blood and cardiac iron levels activated Nrf2 expression less than Fer-1, which is potentially related to Nrf2 regulation of iron storage, metabolism, and transport proteins[48]. During iron accumulation, Nrf2-mediated HMOX1 expression catalyzes heme cleavage to form biliverdin, CO, and Fe2+, which may act as a ferroptotic driver[49]. Nrf2 facilitates iron accumulation and defense transcription[50], and Nrf2 pathway components, such as peroxiredoxins, are efficient cardiovascular ROS scavengers[51]. Therefore, pharmacological Nrf2 modulation to induce or inhibit ferroptosis may be important for SiO2-induced organ damage.

In silicotic mice, no myocardial histopathological changes were observed after 84 d of exposure; however, late-stage clinical silicosis can cause heart failure. We plan to prolong SiO2 exposure to observe its long-term effects and conduct clinical studies to compare patients. Previous studies have shown that conventional microsized SiO2 can cause inflammation, pulmonary hypertension, and right ventricular structural and functional changes[6,52]. We plan to further investigate mechanisms such as iron accumulation-induced pulmonary arterial endothelial damage to improve our understanding of SiO2-induced myocardial injury.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that SiO2 exposure increases peripheral and myocardial iron levels, causing myocardial ferroptosis and altering the expression of Nrf2 and its downstream genes. These data will enable the exploration and development of new clinical SiO2 treatment and prevention strategies.

-

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that iron overload-mediated ferroptosis is a critical mechanism contributing to SiO2-induced cardiac injury in a silicosis mouse model. Intervention with the ferroptosis inhibitors, ferrostatin-1 and deferoxamine alleviated SiO2-induced mitochondrial damage and cardiotoxicity by reducing lipid peroxidation and iron overload, respectively. These findings suggest that inhibition of ferroptosis by modulating iron homeostasis or lipid peroxidation may be an effective therapeutic strategy to protect against SiO2-induced cardiotoxicity. Overall, this study elucidated the key role of iron-dependent ferroptosis in SiO2-triggered cardiac injury, providing novel insights into the mechanisms of SiO2 cardiotoxicity, which may reveal new approaches to prevent cardiac complications in silicosis.

-

All animal procedures complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the North China University of Science and Technology and were approved by the North China University of Science and Technology Ethics Committee (Protocol No. 2023-SY-014).

doi: 10.3967/bes2024.087

SiO2 Induces Iron Overload and Ferroptosis in Cardiomyocytes in a Silicosis Mouse Model

-

Abstract:

Objective The aim of this study was to explore the role and mechanism of ferroptosis in SiO2-induced cardiac injury using a mouse model. Methods Male C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally instilled with SiO2 to create a silicosis model. Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) and deferoxamine (DFO) were used to suppress ferroptosis. Serum biomarkers, oxidative stress markers, histopathology, iron content, and the expression of ferroptosis-related proteins were assessed. Results SiO2 altered serum cardiac injury biomarkers, oxidative stress, iron accumulation, and ferroptosis markers in myocardial tissue. Fer-1 and DFO reduced lipid peroxidation and iron overload, and alleviated SiO2-induced mitochondrial damage and myocardial injury. SiO2 inhibited Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and its downstream antioxidant genes, while Fer-1 more potently reactivated Nrf2 compared to DFO. Conclusion Iron overload-induced ferroptosis contributes to SiO2-induced cardiac injury. Targeting ferroptosis by reducing iron accumulation or inhibiting lipid peroxidation protects against SiO2 cardiotoxicity, potentially via modulation of the Nrf2 pathway. -

Key words:

- SiO2 exposure /

- Iron overload /

- Ferroptosis /

- Cardiac injury /

- Nrf2

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

注释:1) AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: 2) CONFLICT OF INTEREST: -

Figure 2. Myocardial damage in mice injected with SiO2 (50 mg/mL) after 84 d. (A–C) Creatine kinase isoenzymes (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in serum (n = 6). (D) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for cardiac tissues histopathology (n = 3). (E) Transmission electron micrograph of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes (the yellow asterisks indicate the disappearance of mitochondrial cristae). (F–G) The serum and cardiac malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in indicated groups (n = 6). (H–I) The serum and cardiac superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels in indicated groups (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3. Ferroptosis in cardiac tissue is activated in mice injected with SiO2. (A–B) The serum and cardiac non-heme iron in the control and model groups (n = 6). (C) Prussian blue staining for iron (n = 3). (D–J) The protein (n = 3) and mRNA levels of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) in myocardial tissues of each group (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Figure 4. Inhibition of ferroptosis significantly reduces heart damage in mice injected with SiO2. (A–C) The levels of CK, AST and LDH in serum (n = 6). (D–G) The serum and cardiac MDA and SOD levels (n = 6). (H) Transmission electron micrograph of mitochondria in cardiomyocytes (n = 3). (I–J) The serum and cardiac non-heme iron (n = 3). (K) Prussian blue staining for iron (n = 3). (L–P) The protein (n = 3) and mRNA levels of GPX4 and PTGS2 in myocardial tissues of each group (n = 6). *Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Figure 5. The protein and mRNA expression of Nrf2, heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), and xCT in mice injected with SiO2 with or without ferroptosis inhibitor intervention. (A–E) The protein levels of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, and xCT in myocardial tissues (n = 3). (F–I) The mRNA levels of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO1, and xCT in myocardial tissues (n = 6). *Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Table 1. Primer used for qRT-PCR

qPCR Primers Sequence 5’–3’ GPX4 F CGAGCTCGTGTGTGGCTGTTCCCCAGG GPX4 R CCAAGCTTCAGGAAGCAACATTTACTTG PTGS2 F TGCTGTTCCAACCCATGTCA PTGS2 R TGTCAGAAACTCAGGCGTAGT Nrf2 F TGAAGCTCAGCTCGCATTGA Nrf2 R TGCTCCAGCTCGACAATGTT HO-1 F TGCTAGCCTGGTGCAAGATACT HO-1 R AGGCCACATTGGACAGAGTT xCT F TGCAATCAAGCTCGTGAC xCT R AGCTGTATAACTCCAGGGACTA NQO1 F GCTGCCATGTACGACAACGG NQO1 R ATGCCACTCTGAATCGGCCA β-actin F TGGGACGATATGGAGAAGAT β-actin R ATTGCCGATAGTGATGACCT -

[1] Walters EH, Shukla SD. Silicosis: pathogenesis and utility of animal models of disease. Allergy, 2021; 76, 3241−2. [2] Hoy RF, Baird T, Hammerschlag G, et al. Artificial stone-associated silicosis: a rapidly emerging occupational lung disease. Occup Environ Med, 2018; 75, 3−5. [3] Gołębiowski T, Kuźniar J, Porażko T, et al. Multisystem amyloidosis in a coal miner with silicosis: is exposure to silica dust a cause of amyloid deposition? Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022; 19, 2297. [4] Koskinen H. Symptoms and clinical findings in patients with silicosis. Scand J Work Environ Health, 1985; 11, 101−6. [5] Liu X, Jiang QT, Wu PH, et al. Global incidence, prevalence and disease burden of silicosis: 30 years' overview and forecasted trends. BMC Public Health, 2023; 23, 1366. [6] Jandová R, Widimský J, Eisler L, et al. Long-term prognosis of pulmonary hypertension in silicosis. Cor Vasa, 1980; 22, 221−37. [7] Milovanović A, Nowak D, Milovanović A, et al. Silicotuberculosis and silicosis as occupational diseases: report of two cases. Srp Arh Celok Lek, 2011; 139, 536−9. [8] Vranic S, Shimada Y, Ichihara S, et al. Toxicological evaluation of SiO2 nanoparticles by zebrafish embryo toxicity test. Int J Mol Sci, 2019; 20, 882. [9] Maser E, Schulz M, Sauer UG, et al. In vitro and in vivo genotoxicity investigations of differently sized amorphous SiO2 nanomaterials. Mutat Res/Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen, 2015; 794, 57−74. [10] Pellen-Mussi P, Tricot-Doleux S, Neaime C, et al. Evaluation of functional SiO2 nanoparticles toxicity by a 3D culture model. J Nanosci Nanotechnol, 2018; 18, 3148−57. [11] Zhang FF, You XY, Zhu TT, et al. Silica nanoparticles enhance germ cell apoptosis by inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Toxicol Sci, 2020; 45, 117−29. [12] Liu W, Hu T, Zhou L, et al. Nrf2 protects against oxidative stress induced by SiO2 nanoparticles. Nanomedicine, 2017; 12, 2303−18. [13] Nho R. Pathological effects of nano-sized particles on the respiratory system. Nanomed: Nanotechnol, Biol Med, 2020; 29, 102242. [14] Guerrero-Beltrán CE, Bernal-Ramírez J, Lozano O, et al. Silica nanoparticles induce cardiotoxicity interfering with energetic status and Ca2+ handling in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2017; 312, H645−61. [15] Otsuki T, Hayashi H, Nishimura Y, et al. Dysregulation of autoimmunity caused by silica exposure and alteration of Fas-mediated apoptosis in T lymphocytes derived from silicosis patients. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol, 2011; 24, 11S−6S. [16] Delgado-García D, Miranda-Astorga P, Delgado-Cano A, et al. Workers with suspected diagnosis of silicosis: a case study of sarcoidosis versus siderosis. Healthcare, 2023; 11, 1782. [17] Liu TY, Bao R, Wang QS, et al. SiO2-induced ferroptosis in macrophages promotes the development of pulmonary fibrosis in silicosis models. Toxicol Res, 2022; 11, 42−51. [18] Tang DL, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis. Curr Biol, 2020; 30, R1292−7. [19] Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell, 2014; 156, 317−31. [20] Kerins MJ, Ooi A. The roles of NRF2 in modulating cellular iron homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2018; 29, 1756−73. [21] Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R, Zhang DD. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol, 2019; 23, 101107. [22] Ma J, Wang JQ, Ma CJ, et al. Wnt5a/Ca2+ signaling regulates silica-induced ferroptosis in mouse macrophages by altering ER stress-mediated redox balance. Toxicology, 2023; 490, 153514. [23] Li N, Chang MY, Zhou Q, et al. Activation of AMPK signalling by Metformin: implication an important molecular mechanism for protecting against mice silicosis via inhibited endothelial cell-to-mesenchymal transition by regulating oxidative stress and apoptosis. Int Immunopharmacol, 2023; 120, 110321. [24] Liu PF, Feng YT, Li HW, et al. Ferrostatin-1 alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting ferroptosis. Cell Mol Biol Lett, 2020; 25, 10. [25] Teixeira KC, Soares FS, Rocha LGC, et al. Attenuation of bleomycin-induced lung injury and oxidative stress by N-acetylcysteine plus deferoxamine. Pulm Pharmacol Ther, 2008; 21, 309−16. [26] Ali MK, Kim RY, Brown AC, et al. Critical role for iron accumulation in the pathogenesis of fibrotic lung disease. J Pathol, 2020; 251, 49−62. [27] Li N, Wang W, Zhou H, et al. Ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis is involved in sepsis-induced cardiac injury. Free Radic Biol Med, 2020; 160, 303−18. [28] Yazaki K, Yoshida K, Hyodo K, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to silicosis and right upper pulmonary artery occlusion with bronchial anthracofibrosis. Respir Med Case Rep, 2021; 34, 101522. [29] Voelkel NF, Quaife RA, Leinwand LA, et al. Right ventricular function and failure: report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on cellular and molecular mechanisms of right heart failure. Circulation, 2006; 114, 1883−91. [30] Gellissen J, Pattloch D, Möhner M. Effects of occupational exposure to respirable quartz dust on acute myocardial infarction. Occup Environ Med, 2019; 76, 370−5. [31] Chen Z, Meng H, Xing GM, et al. Age-related differences in pulmonary and cardiovascular responses to SiO2 nanoparticle inhalation: nanotoxicity has susceptible population. Environ Sci Technol, 2008; 42, 8985−92. [32] Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK, et al. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2009; 54, 2129−38. [33] Andresdottir MB, Sigfusson N, Sigvaldason H, et al. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, an independent predictor of coronary heart disease in men and women: the Reykjavik study. Am J Epidemiol, 2003; 158, 844−51. [34] Nemmar A, Yuvaraju P, Beegam S, et al. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage in multiple organs of mice acutely exposed to amorphous silica nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed, 2016; 11, 919−28. [35] Boovarahan SR, Kurian GA. Mitochondrial dysfunction: a key player in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases linked to air pollution. Rev Environ Health, 2018; 33, 111−22. [36] Lozano O, Silva-Platas C, Chapoy-Villanueva H, et al. Amorphous SiO2 nanoparticles promote cardiac dysfunction via the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in rat heart and human cardiomyocytes. Part Fibre Toxicol, 2020; 17, 15. [37] Falcon-Rodriguez CI, Osornio-Vargas AR, Sada-Ovalle I, et al. Aeroparticles, composition, and lung diseases. Front Immunol, 2016; 7, 3. [38] Fan CJ, Graff P, Vihlborg P, et al. Silica exposure increases the risk of stroke but not myocardial infarction-A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One, 2018; 13, e0192840. [39] Jiang XJ, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2021; 22, 266−82. [40] Zhao WK, Zhou Y, Xu TT, et al. Ferroptosis: opportunities and challenges in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2021; 2021, 9929687. [41] Li T, Tan Y, Ouyang S, et al. Resveratrol protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via attenuating ferroptosis. Gene, 2022; 808, 145968. [42] Sumneang N, Siri-Angkul N, Kumfu S, et al. The effects of iron overload on mitochondrial function, mitochondrial dynamics, and ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2020; 680, 108241. [43] Wang H, An P, Xie EJ, et al. Characterization of ferroptosis in murine models of hemochromatosis. Hepatology, 2017; 66, 449−65. [44] Sun CF, Peng F, Li JF, et al. Ferroptosis-specific inhibitor ferrostatin-1 relieves H2O2-induced redox imbalance in primary cardiomyocytes through the Nrf2/ARE pathway. Dis Markers, 2022; 2022, 4539932. [45] Chen H, Zhu J, Le YF, et al. Salidroside inhibits doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy by modulating a ferroptosis-dependent pathway. Phytomedicine, 2022; 99, 153964. [46] Zhang W, Qian SH, Tang B, et al. Resveratrol inhibits ferroptosis and decelerates heart failure progression via Sirt1/p53 pathway activation. J Cell Mol Med, 2023; 27, 3075−3089. [47] Anandhan A, Dodson M, Schmidlin CJ, et al. Breakdown of an ironclad defense system: the critical role of NRF2 in mediating ferroptosis. Cell Chem Biol, 2020; 27, 436−47. [48] Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T. Targeting ferroptosis to iron out cancer. Cancer Cell, 2019; 35, 830−49. [49] Chang LC, Chiang SK, Chen SE, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 mediates BAY 11-7085 induced ferroptosis. Cancer Lett, 2018; 416, 124−37. [50] Tonelli C, Chio IIC, Tuveson DA. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2018; 29, 1727−45. [51] Ooi BK, Goh BH, Yap WH. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases: involvement of Nrf2 antioxidant redox signaling in macrophage foam cells formation. Int J Mol Sci, 2017; 18, 2336. [52] Zelko IN, Zhu JX, Ritzenthaler JD, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling in mice exposed to crystalline silica. Respir Res, 2016; 17, 160. -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links