-

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5), a major air pollutant rich in toxic organic compounds, induces lung injury primarily through oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby contributing to diseases such as asthma, fibrosis, and lung cancer. It triggers inflammatory responses by promoting immune cell infiltration and releasing pro-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and MIP-1α. It also causes excessive ROS production, disrupts the redox balance, and exacerbates oxidative damage and inflammation in lung tissue[1-4]. Although PM2.5 has been shown to induce ferroptosis via iron overload and oxidative stress, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. This study aimed to establish a PM2.5 inhalation exposure model to explore lung toxicity related to ferroptosis mechanisms.

A total of 45 male C57BL/6J mice (6–8 weeks old) were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 15 per group): the filtered (air filtered through a Teflon membrane without PM2.5, FA), unfiltered PM2.5 (unfiltered air with PM2.5, UA), and concentrated PM2.5 air (with PM2.5 concentrations 5–10 times that of normal air, CA), and exposed for 16 weeks. The concentrations of PM2.5 in each toxicity chamber and the body weights of the mice were recorded throughout the experiment. After exposure, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. After exposure, lung tissue samples from each group were stored in a –80 °C freezer or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological examination for subsequent measurements.

Metabolite detection in the lung tissue was performed according to an adapted method with modifications, and relative quantitative metabolite analysis was conducted using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. The detailed operational procedures and parameter settings are provided in the supporting information (SI). To systematically investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of PM2.5 on iron metabolism, we further measured iron ions, inflammatory cytokines, and oxidative damage-related markers using ELISA kits; all details can be found in the SI.

The experimental results are expressed as the means ± SD. Metabolomic data were processed using ProFinder software for raw LC-MS data extraction, and univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were conducted using Analyst 1.6.3 software. Differential metabolites were identified through univariate (t-tests, fold change) and multivariate [principal component analysis (PCA), orthogonal partial-least-squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA)] analyses using variable importance in projection (VIP) ≥ 1 and P < 0.05, followed by KEGG pathway enrichment. Detailed analytical methods are provided in the SI.

All animal experiments and euthanasia procedures were approved by and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee of Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethical Review of the Institute of Environmental and Health-Related Product Safety, China CDC (No. 2022H0003).

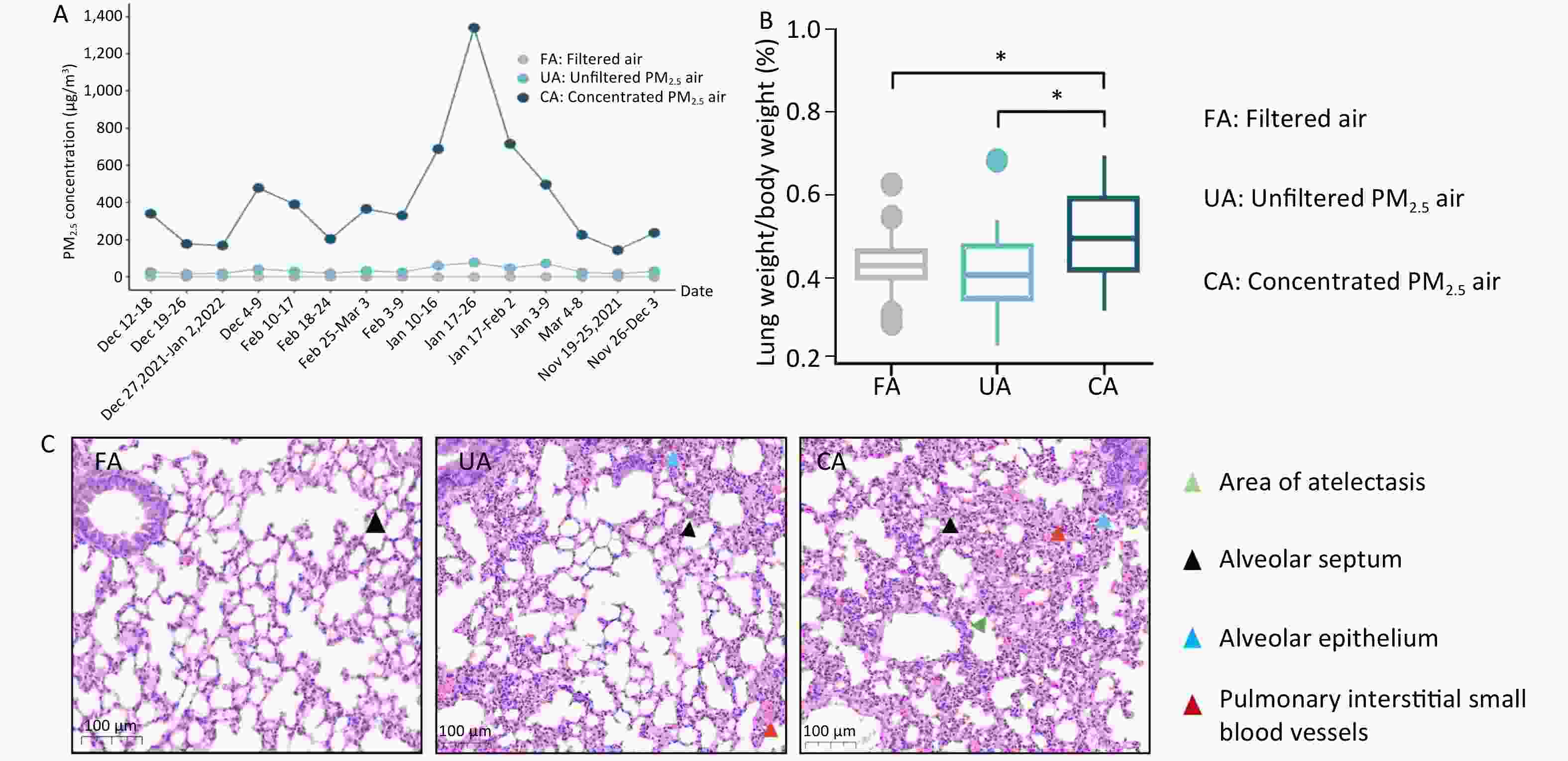

As shown in Figure 1A, the period of animal inhalation exposure lasted for 16 weeks and the weekly average concentrations to which the FA, UA, and CA groups were exposed were 0, 18.20–77.92, and 144.8–1339.79 μg/m3, respectively. In addition, the lung-weight-to-body-weight ratio was not elevated in the UA group, but a statistically significant increase was observed in the CA group compared with that in the FA group (Figure 1B; P < 0.05). Histological examination revealed clear changes in both UA and CA groups. Compared with the FA group, focal pulmonary interstitial edema, widened alveolar septa, dilated and congested small blood vessels, and exudation of cellulose-like substances were observed in both the UA and CA groups. In addition, a small amount of inflammatory cell infiltration in the interstitium, alveolar epithelial hyperplasia, and a tendency toward atelectasis in focal areas with a tendency toward consolidation were observed, indicating lung injury in the CA group (Figure 1C). These results are consistent with those of previous research showing that PM2.5, can cause lung tissue damage, such as destruction of alveolar structures (thickening of alveolar walls or rupture of alveolar septa) and infiltration of inflammatory cells[5].

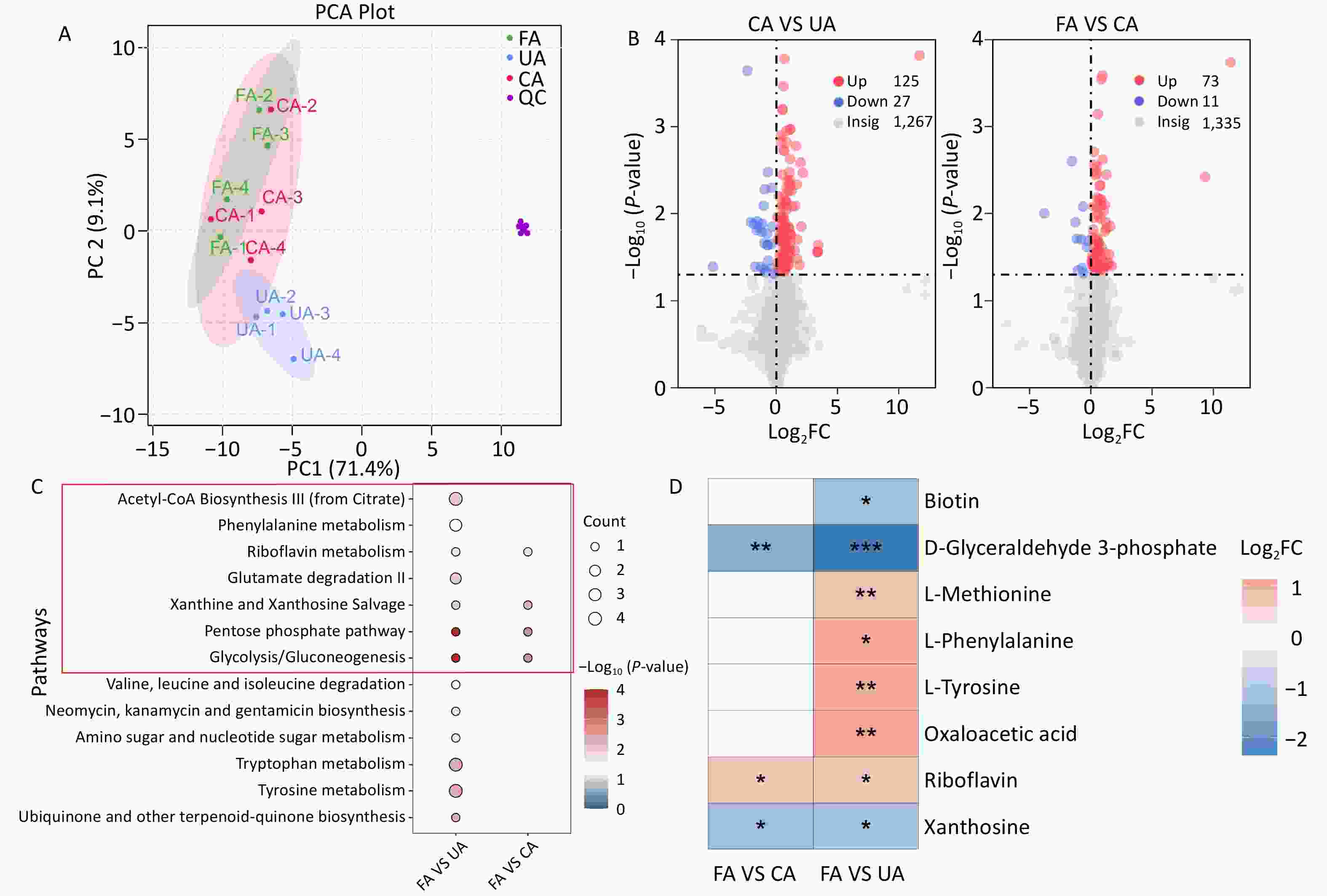

The PCA score plot indicated that the experimental samples demonstrated good repeatability and stability (Figure 2A). The results revealed a significant separation between the metabolites of the FA and UA groups, with principal components PC1 and PC2 accounting for 26.9% and 20.1% of the variance, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1A). Similarly, a clear separation trend was observed between the FA and CA groups, with PC1 and PC2 accounting for 25.4% and 18.7% of the variance, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1B). The OPLS-DA score plot showed that the FA and UA and FA and CA groups were distributed across distinct regions. The goodness-of-fit and predictive ability values (FA vs. UA: R2X = 0.229, R2Y = 0.94, Q2 = 0.762; and FA vs. CA: R2X = 0.182, R2Y = 0.901, Q2 = 0.542) suggested that the OPLS-DA model had good fitting and predictive capabilities (Supplementary Figure S1C, 1D). Differential metabolites were identified using the VIP value from the OPLS-DA model and P-value from statistical analysis. Metabolites with VIP > 1.0, P < 0.05, or -Log10 (P-value) > 1.32 were considered significant, with Log2FC > 0 indicating upregulation and Log2FC < 0 indicating downregulation. A total of 152 differential metabolites were identified between the FA and UA groups, and 84 between the FA and CA groups. Compared with the FA group, the UA group showed 125 upregulated and 27 downregulated metabolites, whereas the CA group showed 73 upregulated and 11 downregulated metabolites (Figure 2B). There were 19 differential metabolites between the two groups (Supplementary Figure S1E). Subsequent KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified 13 differential metabolic pathways in the UA group, including seven related to ferroptosis. Four different metabolic pathways related to ferroptosis were identified in the CA group (Figure 2C). Differential metabolites enriched in the above metabolic pathways included eight types of chemicals. Among these, D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, riboflavin, and pyrimidine, the three differential metabolites, were enriched in both groups (Supplementary Table S6, Figure 2D). The results indicate that the UA group exhibited a greater number of differential metabolites compared with the CA group (152 vs. 84). In toxicology, high-dose exposure is expected to induce stronger and more widespread biological effects, including severe metabolic disruptions. A plausible explanation for this finding is that a high concentration of PM2.5 may cause devastating damage to cells within a short period, leading to extensive, non-specific cell death (e.g., necrosis). Under such conditions, metabolic signatures specific to the regulated pathways are difficult to detect, resulting in fewer significantly altered metabolites in the data. In contrast, chronic low-dose exposure allows cells to adapt gradually, triggering a series of specific programmed defense or injury response pathways (such as ferroptosis, antioxidant stress response, and DNA repair). Activation of these pathways leads to the accumulation or depletion of specific metabolites, thereby producing a clear, detectable pattern of numerous differential metabolites in metabolomic profiling, reflecting a systemic, pathway-driven response. Combined with the histopathological examination showing more severe lung injury in the CA group than that in the UA group, these results further revealed that high-dose exposure caused metabolic collapse, resulting in fewer differential metabolites.

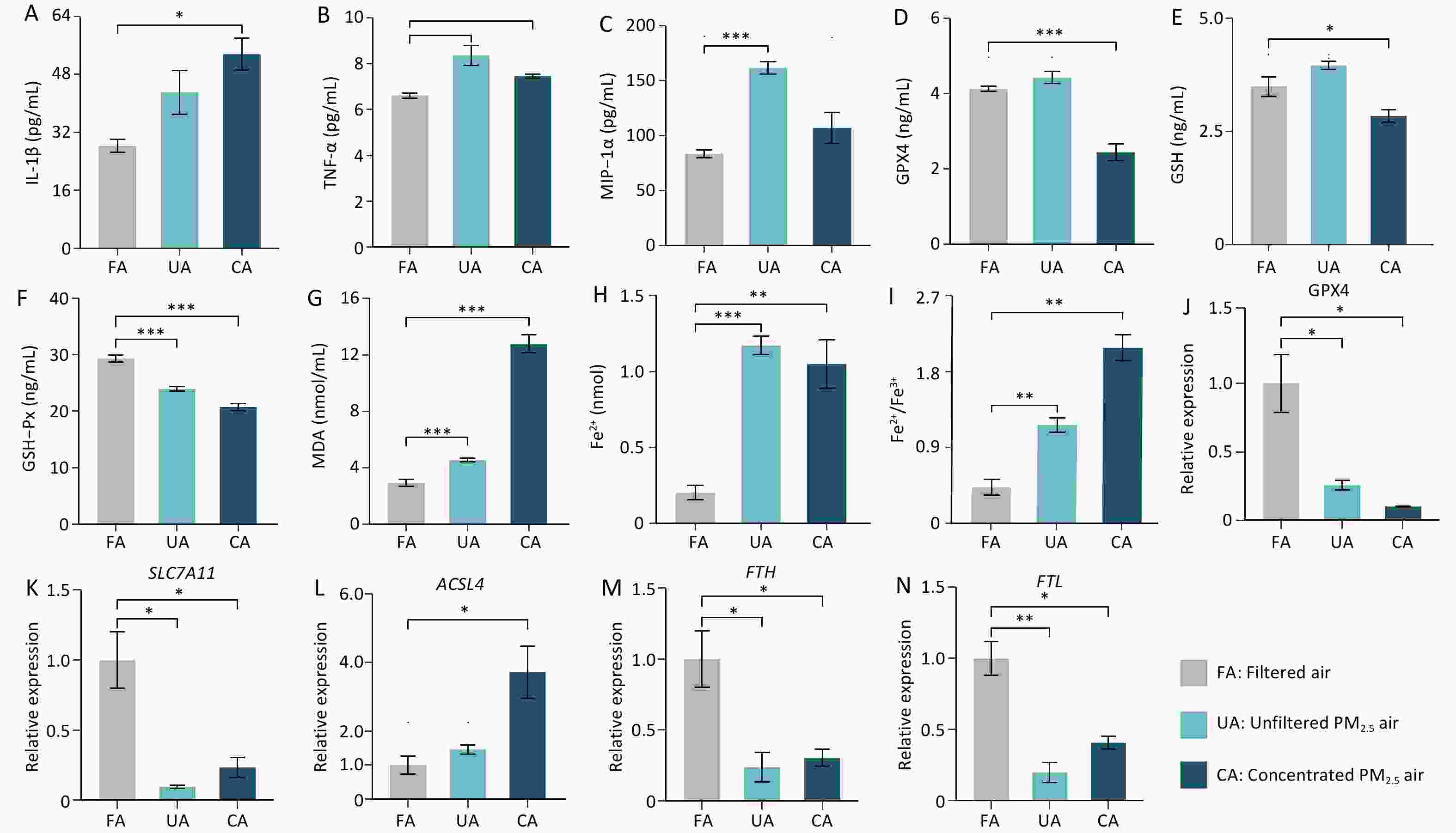

Both PM2.5-exposed groups showed elevated levels of TNF-α, MIP-1α, and MDA compared with controls, but with distinct cytokine profiles: IL-1β increased significantly only in the CA group, whereas MIP-1α increased significantly only in the UA group, indicating differential, dose-dependent inflammatory responses. In addition, the results also demonstrated significant ferroptosis induction by PM2.5, as evidenced by the decreased levels of GPX4, GSH, and GSH-Px, increased MDA, and increased Fe2+ concentrations and Fe2+/Fe3+ ratios in the lung tissues of both UA and CA groups compared with the controls; the Fe2+/Fe3+ ratio showed a clear dose-dependent increase. To further understand how PM2.5 triggers lung tissue damage in mice through ferroptosis, we examined changes in the expression levels of ferroptosis-related genes in mouse lung tissue following PM2.5 exposure. The results showed that, compared with those in the FA group, the expression levels of GPX4, SLC7A11, FTH, and FTL genes in mouse lung tissue were significantly downregulated in the UA and CA groups (Figures 4J-K, 4M-N). In contrast, ACSL4 expression was only significantly upregulated in the CA group (Figure 4L).

The results suggest that PM2.5 activates the ferroptosis pathway through multi-target synergistic effects: 1) Comprehensive inhibition of the antioxidant defense system: the significant downregulation of GPX4 and SLC7A11 indicates a systemic weakening of cellular antioxidant capacity, impairing the effective clearance of lipid peroxides, which is a key prerequisite for ferroptosis[6,7]; 2) Exacerbated iron metabolism imbalance: the downregulation of FTH and FTL suggests a reduced capacity for iron storage, leading to an increase in intracellular labile iron pool (LIP)—the catalytically active free iron[8].— which provides ample catalyst (Fe2+) for the Fenton reaction, thereby accelerating the production of ROS and lipid peroxides; 3) Selective activation of pro-ferroptotic factors: ACSL4 was only significantly upregulated in the high-dose (CA) group, indicating that, under high-concentration, acute exposure, cell membranes are substantially "armed" with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that are susceptible to attack[9]. This enabled a vigorous burst of lipid peroxidation, resulting in rapid membrane damage and cell death. Moreover, different exposure patterns led to distinct emphases in the mechanisms of damage: 1) Long-term, low-dose exposure (UA group): Primarily causes gradual damage accumulation by continuously suppressing the antioxidant system (GPX4, SLC7A11↓) and disrupting iron storage (FTH, FTL↓). The absence of ACSL4 upregulation indicated that membrane lipid remodeling was not significant, resulting in progressive incremental injury. This is consistent with the previously observed greater number of differential metabolites, which reflected a systemic adaptive/stress response. 2) High-dose exposure (CA group): Exhibits all damage mechanisms observed in the UA group (antioxidant suppression and iron storage disruption), but additionally activates ACSL4, leading to cell membranes enriched with oxidizable polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). This is akin to "adding fuel to the fire," enabling lipid peroxidation to occur violently and rapidly, catalyzed by high levels of Fe2+, ultimately resulting in more severe acute cell death and tissue damage consistent with the more severe histopathological findings. Our previous in vitro experiments demonstrated that the organic components of PM2.5 can induce ferroptosis in the lungs, and that oxidative damage, inflammatory factors, and ferroptosis-related genes can be alleviated by the addition of a ferroptosis inhibitor[10].

In summary, our data demonstrated that PM2.5 induces lung injury through a multifaceted mechanism centered on ferroptosis, driven by the interplay of oxidative stress, iron dysregulation, inflammation, and metabolic reprogramming. This multi-target synergistic effect, particularly the dose-dependent upregulation of ACSL4, explains why high-dose exposure (CA group) caused more severe acute lung injury, whereas low-dose exposure (UA group) triggered a broader, more systemic chronic stress response. This provides a complete molecular evidence chain—from genes to proteins and then to metabolites—demonstrating that PM2.5 induces lung injury via the ferroptosis pathway. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

doi: 10.3967/bes2025.167

-

Writing—Original Draft Preparation & Editing: Chong Wang; Methodology: Mengmeng Wang, Wei Huang, Yuehan Long, and Yingyang He; Data Analysis: Wen Gu and Ying Shi; Funding Acquisition: Yuanyuan Chen, Chao Wang, and Lian Duan.

Animal experiments were approved by the Committee of Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethical Review of the Institute of Environmental Health and Health, China CDC (IACUC Issue No. 2022H0003).

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) Authors’ Contributions: 2) Ethics: -

[1] Shaddick G, Thomas ML, Amini H, et al. Data integration for the assessment of population exposure to ambient air pollution for global burden of disease assessment. Environ Sci Technol, 2018; 52, 9069−78. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02864 [2] Liu KM, Hua SC, Song L. PM2.5 exposure and asthma development: the key role of oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2022; 2022, 3618806. doi: 10.1155/2022/3618806 [3] Chen QQ, Wang YL, Yang L, et al. PM2.5 promotes NSCLC carcinogenesis through translationally and transcriptionally activating DLAT-mediated glycolysis reprograming. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2022; 41, 229. doi: 10.1186/s13046-022-02437-8 [4] Otoupalova E, Smith S, Cheng GJ, et al. Oxidative stress in pulmonary fibrosis. Compr Physiol, 2020; 10, 509−47. doi: 10.1002/j.2040-4603.2020.tb00120.x [5] Zhang N, Li P, Lin H, et al. IL-10 ameliorates PM2.5-induced lung injury by activating the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol, 2021; 86, 103659. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2021.103659 [6] Yuan Y, Zhai YY, Chen JJ, et al. Kaempferol ameliorates oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation-induced neuronal ferroptosis by activating Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 axis. Biomolecules, 2021; 11, 923. doi: 10.3390/biom11070923 [7] Ye YZ, Chen A, Li L, et al. Repression of the antiporter SLC7A11/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 axis drives ferroptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells to facilitate vascular calcification. Kidney Int, 2022; 102, 1259−75. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.07.034 [8] Chen Y, Zhang JQ, Tian Y, et al. Iron accumulation in ovarian microenvironment damages the local redox balance and oocyte quality in aging mice. Redox Biol, 2024; 73, 103195. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2024.103195 [9] Ding KY, Liu CB, Li L, et al. Acyl-CoA synthase ACSL4: an essential target in ferroptosis and fatty acid metabolism. Chin Med J (Engl), 2023; 136, 2521−37. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002533 [10] Wang MM, Long YH, Chen YY, et al. A study on bronchial epithelial cell injury induced by PM2.5 organic extracts through ferroptosis. J Environ Hyg, 2024; 14, 303−11,361. (In Chinese) -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links