-

According to the data from the Chinese HIV/AIDS case reporting system, there were 577, 423 HIV/AIDS cases in China until the end of 2015, and approximately one-fifth were newly diagnosed[1]. In recent years, young students account for 14%-15% of these new cases. The annual number of HIV-infected young students in 2014 was approximately five times greater than that of 2008[2]. In the first half year of 2015, incidence of infections among young students jumped by 35%, which was higher the numbers observed in the previous years. Among them, 98% were sexually transmitted[3]. There are over 2000 universities in China; thus, it is imperative to explore an effective intervention to control the HIV epidemic among young students.

-

At present, using condoms in a proper manner during the entirety of sexual intercourse is an affordable and effective method for HIV prevention; therefore, this is the highly recommended strategy by the World Health Organization (WHO)[4]. According to a serial cross-sectional study conducted between 2010 and 2015, the proportion of college students having sexual intercourse in China was 8.3%. Approximately 48.5% of these students had never used condoms during sexual inter course[5]. Other studies have observed the same pattern, that the prevalence of condom use among Chinese young students was < 50%[6-7]. These results indicate that there is a significant percentage of Chinese young students who have not used condoms during sexual intercourse, hence resulting in an increase in HIV vulnerability. School-based HIV education is an effective strategy primarily employed to promote condom use among Chinese college students. Numerous studies have confirmed that the frequency of condom-use behavior, or the intention of doing so, in the intervention groups were significantly higher than that in the control groups[8-9]. However, the majority of these school-based HIV educational interventions in China lacked a theoretical basis[10]. Accordingly, implementing a theory-based HIV educational approach is academically valuable and is a significant topic for future studies.

-

In recent years, the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission has emphasized the need to improve the HIV-risk perception in college students to avoid the increased risk behaviors among them. A fear appeal as a persuading strategy, which is widely used in health promotion fields, may be applied to future school-based HIV education in China. The fear appeal acts by presenting the serious consequences of certain risk behaviors to audiences and arousing their fear so that the protective measures will be executed[11]. The fear appeal is a commonly used strategy for HIV prevention[12-14] and numerous studies have proved its efficacy in the condom promotion among college students. However, no such study was conducted in China[15-17]. Therefore, it is critical to verify the correlation between risk perception and condom use before the implementation of the fear appeal strategy in Chinese college students.

The extended parallel process model (EPPM) proposed by White in 1992 is the most recent model of fear appeal[18]. According to EPPM, two appraisals-threat and efficacy appraisals-were gradually initiated in the process of fear appeal[19]. Individuals evaluated the threat information through the perceived severity and susceptibility of a negative consequence. The efficacy appraisal included response efficacy and self-efficacy, which respectively meant the belief in and the executive ability of the preventive measure[20]. As a result, individuals with strong risk perception and self-efficacy are inclined to execute the protective behaviors.

Numerous health behavior models have confirmed that self-efficacy had a decisive effect on behaviors[21-22], such like the information-motivation-behavioral skills model (IMB)[23], the health belief model (HBM)[24] and the theory of reasoned action (TRA)[25]. These models have demonstrated great abilities to predict condom-use self-efficacy. Previous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of the IMB model, particularly among Chinese college students[26-27]. Furthermore, these theories share the same idea that the HIV-risk-reduction motivation results from the perceived threat and the desire to avoid the potential negative outcome, and it had a direct effect on condom-use self-efficacy. According to these models, motivation was defined as one's attitude toward precautions against HIV infections [henceforth referred to as 'HIV precaution (s)'] and relevant subjective norms associated with these precautions[28]. That is, the attitude toward HIV precautions may play an important role between the perceived risk and HIV-precaution self-efficacy.

Apart from the variables involved in these theories, premarital sex, a risk factor for HIV infection, has become prevalent among Chinese young students[29]. Certain studies indicated that the HIV-threat perception was a predictor of the premarital sexual abstinence among university students[30-31]. Zhang et al.[32]additionally stated that the intention to engage in premarital sex (intent-to-premarital-sex) would affect the actual sexual behaviors among Chinese adolescents. Thus, it may be a mediator between HIV-risk perception and condom use among Chinese college students.

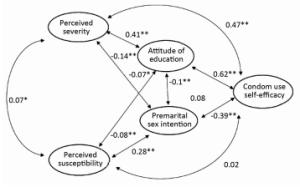

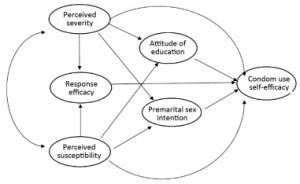

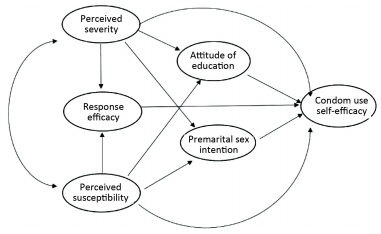

Because of the low proportion of sexual behaviors among Chinese college students and the fact that sexual intercourse is a traditionally sensitive topic in China, few students may ascribe to the sample size of this survey. Furthermore, self-efficacy has a strong prediction effect on behaviors[20, 33-34]. Thus, in the present study, the procedure of HIV-threat perception act on condom-use self-efficacy was assessed instead of behavior. The initial hypothesized integrated model, according to the theory of EPPM, other health behavior models similar to IMB, and the potential influence of intent-to-premarital-sex on condom use, is demonstrated in Figure 1.

-

The present cross-sectional study obtained ethical approval by the ethical committee of China (NCAIDS) and was conducted in Guangzhou and Harbin in September 2015. These particular two cities were selected as study sites because of the yearly increase of HIV-infection rates in college students, and the fact that they are an example of a typical city in Northern and Southern China. Guangzhou, the provincial capital of Guangdong province in south China, has a total of over 100 universities. In 2012, the proportion of new cases among the college student in Guangzhou was five times that of 2002[35]. Similarly, AIDS has rapidly spread among college students in Harbin, the provincial capital of Heilongjiang. In Harbin, the new cases of young students in 2015 were almost three times higher than 2013[36]. In the present survey, a total of 3, 081 students, aged 17-21 years, were recruited from seven universities and the response rate was 96.5%.

-

Two-stage cluster sample design was used in the current study. In the first stage, seven universities were randomly sampled from Guangzhou and Harbin. In China, the major subjects of the first-grade students are the public basic courses; thus, the HIV awareness would not be affected by the specialized knowledge among freshmen. We randomly selected three classes in the first grade within each university and obtained informed consent from all students before the survey. All students were informed regarding the voluntary nature of participation, and those who did not complete the questionnaires for various reasons were excluded. Students who were willing to participate in this survey completed an anonymous questionnaire written in Chinese at an appointed classroom.

-

On the basis of the construct of the integrated model, we developed a structured self-administered questionnaire. The original items pool was compiled by performing a literature review and consulting experts from health education, psychology, communications, and epidemiology. The final version of the questionnaire was created following numerous rounds of amendments. It consisted of seven aspects, including information on demographics, severity of and susceptibility to HIV, attitude to HIV health education, intent-to-premarital-sex, response efficacy, and condom-use self-efficacy. The levels of perceived severity of and perceived susceptibility to HIV were evaluated by five items according to the Perceived Risk of HIV Scale (PRHS)[37], and their Cronbach's α coefficients were 0.67 and 0.79, respectively. Condom-use self-efficacy was assessed by three items in accordance with the Condom-Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES)[38] and the Cronbach's α coefficient was 0.67. As no maturity scales existed for reference, the items of response efficacy, attitude toward HIV education and intent-to-premarital-sex were formulated according to the related studies and experts' advice. The Cronbach's α coefficients were 0.55, 0.64, and 0.60, respectively. The details of the questionnaire are presented in Table 1. The answers of the questionnaire were in a scoring system: Students were asked to rate their agreement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Students (n=2, 973)

Characteristic N % Age < 20 2, 249 75.3 ≥20 699 23.5 Gender Male 1, 387 46.7 Female 1, 586 53.3 Survey city Guangzhou 2, 107 70.9 Harbin 866 29.1 -

SPSS 13.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data process and analysis, including interpolation of missing values, description of statistics of demographic characteristics and measurements of variables, internal reliability, construct validity and Mann-Whitney U-test. IBM SPSS AMOS 17.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for structure equation modeling (SEM). SEM is a multi-statistics method, which fits theoretical models with sample data in two steps, as follows[39]: (ⅰ) confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) tests the fitting degree between the sample data and hypothetical construct, thus determining the structural validity; (ⅱ) path analysis, which follows a reasonable result of CFA, aims to verify the rationality of structure model and illustrate the causal link among the major latent variables. Through SEM, we could estimate coefficients of variables as well as direct, indirect, and total effects among latent variables in the regression model. Indices, including chi-square goodness-of-fit test (χ2/df), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to evaluate the model fitness. In general, the criteria to assess the model were: χ2/df < 5[40], GFI > 0.9, CFI > 0.9[41], and RMSEA < 0.05[42].

-

Table 1 describes the participants' demographic characteristics. Among 2, 973 valid participants, 46.7% were male and 53.3% were female. An approximate of 75.3% students were aged < 20 years, and the average age was 18.6 years (s=0.8). Finally, an approximate of seven out of 10 students were surveyed from Guangzhou.

-

Results of confirmatory factor analysis are demonstrated in Figure 2. The goodness-of-fit statistics suggested that the structural equation model could be accepted and was appropriate for the data. The standardized regression weights (factor loading) and median scores for all items are listed in Table 2. All factor loadings were above 0.45 (0.47-0.81) and statistically significant (P < 0.05), except for the response efficacy. Because the internal consistency of response efficacy was also below the conservative limitation, this variable was excluded from the subsequent analysis.

Figure 2. Confirmatory factor analysis on the integrated model (n=2, 973). Coefficients are shown above and the goodness-of-fit statistics is: χ2/df=335.4/85=3.95, P < 0.001; CFI=0.91; GFI=0.98; RMSEA=0.03. **P < 0.001, *P < 0.05.

Table 2. Factor Loadings and Median Scores

Item Factor Loading M Perceived severity 8 If you encounter a HIV-infection-risk event, you will feel fear 0.71 9 If HIV cases was detected in your school, you will feel fear 0.55 6 You regard AIDS as a terrible disease 0.70 8 Perceived susceptibility 2 Your friends may be infected with the HIV virus 0.74 3 Your friend may be a HIV carrier 0.81 2 Response efficacy 6 Using condom properly will decrease the HIV-infection risk 0.72 6 Having one sexual partner is an effective way to prevent HIV 0.53 9 Avoiding premarital sex is an effective way to prevent HIV 0.37 9 Attitude of HIV health education 8 HIV education is an effective way to prevent HIV 0.50 8 You would like to study HIV knowledge for HIV prevention 0.57 8 HIV health education is necessary for college students 0.78 10 Intent-to-premarital-sex 6 The possibility of you have sex during university 0.70 2 You approve of premarital sex 0.65 5 Condom-use self-efficacy 7 You have confidence to use a condom during sex 0.65 9 If you didn't use condom during sex, you would regret 0.70 7 If you didn't use condom during sex, you feel fear 0.47 8 -

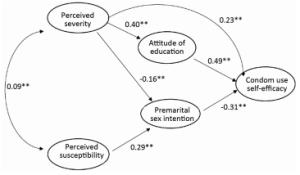

To generate a parsimonious model, the statistically insignificant paths were removed and the final model is depicted in Figure 3. The fit indices suggested that the model was satisfied with the conservative criteria, explaining 50.6% of the variance of condom-use self-efficacy.

Figure 3. The final integrated model. The fit indexes were: χ2/df=243.3/53=4.59, P < 0.001; CFI=0.91; GFI=0.98; RMSEA=0.04. **P < 0.001, *P < 0.05.

Table 3 displays the direct, indirect, and total effect of variables on self-efficacy. Apart from the direct effect (r=0.23), perceived severity had two indirect effects on condom-use self-efficacy; i.e., through the attitude to HIV education (r=0.40) and premarital sex (r=-0.16), respectively. Consequently, the total effect of perceived severity on self-efficacy was positive and strong (0.47). However, perceived susceptibility mediated by intent-to-premarital-sex (r=0.29) had an indirect and weak impact on self-efficacy (-0.06). Furthermore, the attitude toward HIV education (r=0.49) and intent-to-premarital-sex (r=-0.31) had a strong direct effect on condom-use self-efficacy.

Table 3. Effects on Condom-use Self-efficacy

Variable Direct Effects Indirect Effects Total Effects Perceived severity 0.23 0.24 0.47 Perceived susceptibility 0 -0.06 -0.06 Attitude to HIV education 0.49 0 0.49 Intent-to-premarital-sex -0.31 0 -0.31 -

The results of the rank-sum test demonstrated that male students perceived higher susceptibility, stronger intent-to-premarital-sex and lower condom-use self-efficacy compared with the female students. The mean ranks, median and P values are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. The Mann-Whitney U-test between Male and Female Students

Variable Mean Rank Median P Male Female Male Female Perceived susceptibility 1562.6 1420.9 3 2 < 0.001 Intent-to-premarital-sex 1854.8 1165.4 6 6 < 0.001 Condom-use self-efficacy 1122.6 1805.7 7 8 < 0.001 -

The present study aimed to apply the 'fear appeal' integrated model to explore the predictors of condom-use self-efficacy among Chinese college students. In the current study, the total effect of perceived severity on condom-use self-efficacy was relatively strong and positive. Similar results were demonstrated in previous studies among college students[43-44]; however, other studies indicated no association of perceived severity and condom-use self-efficacy[45-46]. The conflicting point was possibly because of the different study populations and measurement scales. Unlike western countries, Chinese culture is predominantly family collectivism. It would be a disgrace to the whole family even the entire clan if a family member was infected with HIV[47]. Hofstede and Minkow[48] demonstrated that collectivists have strong preventive intentions when confronted with threats. Severity perception would be influenced by the cultural orientation of individual[49]. In the present study, apart from the direct effect, perceived severity of HIV had an indirect effect through the attitude to HIV education and intent-to-premarital-sex. The association between perceived severity and intent-to-premarital-sex was consistent with the results of other studies[31, 50]. These findings are in accordance with the rationale of the heath behavior models in the current study. That is, the perceived severity will initiate the HIV-risk-reduction motivation of the individual to take the protective behavior, such as condom use or premarital abstinence, to avert the threat[22, 24]. These conclusions suggest that the perceived severity of HIV may improve condom-use self-efficacy, the HIV-risk-reduction motivation and premarital abstinence intention. Thus, improving the severity perception is necessary for future school-based HIV intervention.

The present study demonstrated that as an aspect of HIV-risk-reduction motivation, the attitude toward HIV health education had a relatively strong effect on condom-use self-efficacy. Certain studies indicated that the coefficient of the HIV-risk-reduction motivation on the self-efficacy was approximately 0.6[51-53]. Furthermore, previous studies also confirmed the critical effect of the motivation on condom-use behavior among Chinese college students[27, 54]. Accordingly, improving the motivation to HIV-risk reduction (attitude toward precaution) will enhance condom-use self-efficacy.

In addition, the present study demonstrated that the perceived susceptibility to HIV was negatively associated with condom-use self-efficacy through the intent-to-premarital-sex. On the one hand, students were likely to assess their own susceptibilities according to their prior sexual experiences, sexual habits, or contact with an HIV-positive individual[55-56]. Individuals who inclined to (already had) to engage themselves in premarital sex or unwillingly used condoms during sexual intercourse are usually perceived more susceptible to HIV infection. This may be a possible explanation for the correlation between the susceptible perception and condom-use self-efficacy. On the other hand, the total effect of the perceived susceptibility on condom-use self-efficacy was extremely weak; thus, it may not have a clinical significance. This was consistent with a meta-analysis demonstrating the relationship between perceived susceptibility and behavior approximated to zero[57]. Other studies have also suggested perceived susceptibility could not predict condom-use self-efficacy among college students[50, 58]. Although the contrary point of view has also existed[59-60], this conflict conclusion may be primarily because of the different study subjects and theoretical model of these studies. In the current study, male students perceived higher susceptibility, stronger intent-to-premarital-sex and lower condom-use self-efficacy compared with the female students. Approximately two-thirds of the students with strong intention to have premarital sex (score above the scale mid-point) were male. Thus, the gender factor may affect the correlation between the perceived susceptibility and condom-use self-efficacy[61]. Many studies confirmed that male individuals express more permissive attitudes toward premarital sex[62-63] and hold a negative attitude toward condom use during sex[64-65]. Therefore, the small effect of perceived susceptibility on condom-use self-efficacy in the present study may ascribe to the gender difference in a larger extent.

Admittedly, there were some limitations in the current study. First, the chronological effects and causal associations of the variables were limited by the present study design. Further longitudinal studies are required. Second, although numerous studies have confirmed the predicting effect of self-efficacy on the behaviors of condom use among university students[54, 59, 66], the self-efficacy was merely a mediate variable between attitude and behavior, and it does not fully represent the actual behaviors. Future research should focus on the behaviors of condom use among this population. Third, this study was a two-stage sampling, the field test excluded first-grade students, which may have limited the generalization from the research findings. Fourth, the internal consistency of the response efficacy was below the conservative criterion and this may be because of the heterogeneity of the study population. Finally, the variable of HIV-risk-reduction motivation is often vague and there is not yet a clear definition. Numerous theories exist with regard to the motivation as the attitude of HIV precaution and the HIV education was the main precaution among college students[67]. The use of attitude toward HIV education as the motivation construct in the present study may have affected the accuracy of correlations.

In conclusion, the integrated model offers an effective theoretical foundation for similar studies in the future. Given the lack of theoretical guidance for school-based fear appeal strategy, the present study is particularly important for HIV education among Chinese college students. The findings highlight the importance of perceived severity, HIV-risk-reduction motivation and the intention to premarital abstinence for condom promotion. Furthermore, considering the gender differences observed in this survey, single-sex HIV education is necessary in school-based HIV/sex intervention.

-

Hello, everyone! We are from the division of public education and information in NCAIDS. We are going to start a survey that is aimed at the Chinese college students. We will appreciate it if you can help us complete the survey questionnaire. Thank you for your time and cooperation.

Please indicate your information.

Age: _______

Gender: _______

Please rate your agreement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree).

Q1. If you encounter a HIV-infection risk event, you will feel fear _______

Q2. If HIV cases was found in your school, you will feel fear _______

Q3. You regard HIV is a terrible disease _______

Q4. The probability of your friends infected by HIV virus _______

Q5. Your friends may be infected with the HIV virus _______

Q6. Using condom properly will decrease the HIV-infection risk _______

Q7. Keeping single sexual partner is an effective way to prevent HIV _______

Q8. Avoiding premarital sex is an effective way to prevent HIV _______

Q9. HIV education is an effective way to prevent HIV _______

Q10. You would like to study HIV knowledge for HIV prevention _______

Q11. HIV health education is necessary for college students_______

Q12. The possibility of you have sex during university _______

Q13. You approve of premarital sex _______

Q14. Your friend may be a HIV carrier _______

Q15. You have confidence to use a condom during sex _______

Q16. If you didn't use condom during sex, you would regret _______

doi: 10.3967/bes2017.013

Correlates of Condom-use Self-efficacy on the EPPM-based Integrated Model among Chinese College Students

-

Abstract:

Objective To explore the predictors of condom-use self-efficacy in Chinese college students according to the extended parallel process model (EPPM)-based integrated model. Methods A total of 3, 081 college students were anonymously surveyed through self-administered questionnaires in Guangzhou and Harbin, China. A structural equation model was applied to assess the integrated model. Results Among the participants, 1, 387 (46.7%) were male, 1, 586 (53.3%) were female, and the average age was 18.6 years. The final integrated model was acceptable. Apart from the direct effect (r=0.23), perceived severity had two indirect effects on condom-use self-efficacy through the attitude to HIV education (r=0.40) and intention to engage in premarital sex (r=-0.16), respectively. However, the perceived susceptibility mediated through the intention to engage in premarital sex (intent-to-premarital-sex) had a poor indirect impact on condom-use self-efficacy (total effect was-0.06). Furthermore, attitude toward HIV health education (r=0.49) and intent-to-premarital-sex (r=-0.31) had a strong direct effect on condom-use self-efficacy. In addition, male students perceived higher susceptibility, stronger intent-to-premarital-sex, and lower condom-use self-efficacy than female students. Conclusion The integrated model may be used to assess the determinants of condom-use self-efficacy among Chinese college students. Future research should focus on raising the severity perception, HIV-risk-reduction motivation, and the premarital abstinence intention among college students. Furthermore, considering the gender differences observed in the present survey, single-sex HIV education is required in school-based HIV/sex intervention. -

Key words:

- HIV infection /

- Condom-use self-efficacy /

- Chinese college students

-

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Students (n=2, 973)

Characteristic N % Age < 20 2, 249 75.3 ≥20 699 23.5 Gender Male 1, 387 46.7 Female 1, 586 53.3 Survey city Guangzhou 2, 107 70.9 Harbin 866 29.1 Table 2. Factor Loadings and Median Scores

Item Factor Loading M Perceived severity 8 If you encounter a HIV-infection-risk event, you will feel fear 0.71 9 If HIV cases was detected in your school, you will feel fear 0.55 6 You regard AIDS as a terrible disease 0.70 8 Perceived susceptibility 2 Your friends may be infected with the HIV virus 0.74 3 Your friend may be a HIV carrier 0.81 2 Response efficacy 6 Using condom properly will decrease the HIV-infection risk 0.72 6 Having one sexual partner is an effective way to prevent HIV 0.53 9 Avoiding premarital sex is an effective way to prevent HIV 0.37 9 Attitude of HIV health education 8 HIV education is an effective way to prevent HIV 0.50 8 You would like to study HIV knowledge for HIV prevention 0.57 8 HIV health education is necessary for college students 0.78 10 Intent-to-premarital-sex 6 The possibility of you have sex during university 0.70 2 You approve of premarital sex 0.65 5 Condom-use self-efficacy 7 You have confidence to use a condom during sex 0.65 9 If you didn't use condom during sex, you would regret 0.70 7 If you didn't use condom during sex, you feel fear 0.47 8 Table 3. Effects on Condom-use Self-efficacy

Variable Direct Effects Indirect Effects Total Effects Perceived severity 0.23 0.24 0.47 Perceived susceptibility 0 -0.06 -0.06 Attitude to HIV education 0.49 0 0.49 Intent-to-premarital-sex -0.31 0 -0.31 Table 4. The Mann-Whitney U-test between Male and Female Students

Variable Mean Rank Median P Male Female Male Female Perceived susceptibility 1562.6 1420.9 3 2 < 0.001 Intent-to-premarital-sex 1854.8 1165.4 6 6 < 0.001 Condom-use self-efficacy 1122.6 1805.7 7 8 < 0.001 -

[1] NCAIDS NCC. Update on the AIDS/STD epidemic in China and main response in control and prevention in December, 2015, China. J AIDS STD, 2016; 21, 2015. (In Chinese) [2] NHFPC. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/xcs/s3574/201504/bee34823e1343d9b6822366ac.shtml.[2015-4-10]. (In Chinese) [3] Wu Z. strategy and situation of AIDS prevention and control in school of China. Chinese Journal of School Health, 2015; 36, 1604-5. (In Chinese) [4] Dick B, Ferguson J, Ross DA. Preventing HIV/AIDS in young people. A systematic review of the evidence from developing countries. Introduction and rationale. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, 2006; 938, 1-13, 317-41. [5] Lin GE, Cui Y, Dong-Min LI. Cross-sectional study on AIDS/HIV related sexual behavior among students from 2010-2015. Chinese Journal of School Health, 2015; 36, 1611-3. (In Chinese) [6] Xiao YK, Wei B, Guo Ping JI, et al. Survey on the knowledge and behavior of AIDS and serological analysis among young students in Anhui Province. Chinese Journal of Disease Control & Prevention, 2013; 36, 837-40. (In Chinese) [7] Tang SK, Liu Y, Huang XM, et al. Investigation of Knowledge about STD and AIDS, Sex Attitude and Sex Behavior among Students from Several Colleges in Guangzhou. Journal of Diagnosis and Therapy on Dermato-venereology, 2014; 21, 328-32. (In Chinese) [8] Li X, Stanton B, Wang B, et al. Cultural adaptation of the focus on kids program for college students in China. Aids Educ Prev, 2008; 20, 1-14. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.1.1 [9] Cheng Y, Lou CH, Mueller LM, et al. Effectiveness of a school-based AIDS education program among rural students in HIV high epidemic area of China. J Adolesc Health, 2008; 42, 184-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.016 [10] Xiao Z, Noar SM, Zeng L. Systematic review of HIV prevention interventions in China: a health communication perspective. Int J Public Health, 2014; 59, 123-42. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0467-0 [11] Rogers RW, Cacioppo JT, Petty R. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. Social Psychophysiology: A Sourcebook, 1983. [12] Witte KR. Preventing AIDS through persuasive communications: fear appeals and preventive-action efficacy. Ann Arbor Michigan University Microfilms International. [13] Witte K, Allen M. A Meta-Analysis of Fear Appeals: Implications for Effective Public Health Campaigns. Health Edu Behav, 2000; 27, 591-615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506 [14] Tannenbaum MB, Hepler J, Zimmerman RS, et al. Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychol Bull, 2015; 141, 178-1204. http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/bul/141/6/1178/ [15] Amsalu S. Response to HIV/AIDS prevention message: based on the extended parallel process model, BAHIR DAR university students, northwest Ethiopia. 2008. [16] Doyore F, Birhanu Z, Kebede Y, et al. Are people controlling the danger or fear for condom use as HIV/AIDS preventive message? An evaluative type of study based on extended parallel process model. Journal of AIDS Clin Res, 2013; 4. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20143106694 [17] Doyore DJF. Evaluating Effectiveness of Abstinence Message Response for HIV/Aids Prevention and Associated Factors among Hadiya Zone College Students using Extended Parallel Process Model. South Ethiopia, 2014; 05, 3. http://search.proquest.com/openview/52cf93b9c40c10f64ccd31fa68d391fd/1.pdf?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2027386 [18] Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Health Commun, 1992; 59, 329-49. doi: 10.1080/03637759209376276 [19] Witte K. Chapter 16-Fear as motivator, fear as inhibitor: Using the extended parallel process model to explain fear appeal successes and failures. Handbook of Communication & Emotion, 1997; 423-50. http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1997-36344-015 [20] Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Pearson Schweiz Ag, 1986. [21] Leventhal H, Watts JC, Pagano F. Effects of fear and instructions on how to cope with danger. J Per Soc Psychol, 1967; 6, 313-21. doi: 10.1037/h0021222 [22] Maddux JE, Rogers RW. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Exp Soc Psychol, 1983; 19, 469-79. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(83)90023-9 [23] Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Williams SS, et al. Empirical tests of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of AIDS-preventive behavior with gay men and heterosexual university students. Health Psychol, 1994; 13, 238-50. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.13.3.238 [24] Rosenstock IM. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Monogr, 1974; 2, 328-35. doi: 10.1177/109019817400200403 [25] Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. PRENTICE-HALL, 1980. [26] Cai Y, Ye X, Shi R, et al. Predictors of consistent condom use based on the Information-Motivation-Behavior Skill (IMB) model among senior high school students in three coastal cities in China. BMC Infect Dis, 2013; 13, 1-8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-1 [27] Zhihao Liu PWMH. Determinants of Consistent Condom Use among College Students in China: Application of the Information-Motivation-Behavior Skills (IMB) Model. PLoS One, 2014; 9, e108976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108976 [28] Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. A Meta-Analysis of Research on Protection Motivation Theory. J Appl Soc Psychol, 2000; 30, 407-29. doi: 10.1111/jasp.2000.30.issue-2 [29] Kaiyan H, Hua T. Survey on the Actuality and the Changes of Sexual Behaviors among the College Students. Journal of Neijiang Normal University, 2016; 31, 111-5. (In Chinese) [30] Gelibo T, Belachew T, Tilahun T. Predictors of sexual abstinence among Wolaita Sodo University Students, South Ethiopia. Reprod Health, 2013; 10, 1-6. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-1 [31] Iriyama S, Nakahara S, Jimba M, et al. AIDS health beliefs and intention for sexual abstinence among male adolescent students in Kathmandu, Nepal: A test of perceived severity and susceptibility. Public Health, 2007; 121, 64-72. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.08.016 [32] Zhang P, Lou C, Szabin L. Analysis on Factors Influencing Adolescent Sex-related Behaviors in Shanghai City under the Structural Equation Model. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics, 2011; 28, 139-41. (In Chinese) [33] Dilorio C, Dudley WN, Soet J, et al. A social cognitive-based model for condom use among college students. Nur Res, 2000; 49, 208-14. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200007000-00004 [34] Mahoney CA. The role of cues, self-efficacy, level of worry, and high-risk behaviors in college student condom use. J Sex Edu Ther, 2015; 21, 103-16. doi: 10.1080/01614576.1995.11074141 [35] Fan LR, Li BU, Qin FJ. Epidemiological features of students living with HIV/AIDS in Guangzhou city during 2002-2012. Chinese Journal of Aids & Std, 2015; 21, 194-6. (In Chinese) [36] Yi L, Shan H, Lan Y, et al. Survey on variation trend of epidemic situation and relevant knowledge andbehavior about HIV/AIDS among Youth/Students in Heilongjiang Province. Chinese Journal of Public Health Management, 2013; 5, 562-4. (In Chinese) [37] Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL. Development of the Perceived Risk of HIV Scale. AIDS Behav, 2012; 16, 1075-83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0003-2 [38] MA LJB, PhD KHB. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. J Am Coll Health, 1991; 39, 219-25. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936238 [39] Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull, 1988; 103, 411-23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 [40] Fox J. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL: Essentials and Advances by Leslie A. Hayduk: Johns Hopkins University Press. Am J Sociol, 1989; 95, 257. https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-pdf/69/1/338/6516734/69-1-338.pdf?frame=sidebar [41] Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Anaysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling, 1999; 6, 1-55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [42] Mcdonald RP, Ho MH. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods, 2002; 7, 64-82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 [43] Meekers D, Klein M. Determinants of condom use among unmarried youth in Yaounde and Douala Cameroon. Washington D. 2001. [44] Ndabarora E, Mchunu G. Factors that influence utilisation of HIV/AIDS prevention methods among university students residing at a selected university campus. SAHARA J, 2014; 11, 202-10. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2014.986517 [45] Bengel J, Belzmerk M, Farin E. The role of risk perception and efficacy cognitions in the prediction of HIV-related preventive behavior and condom use. Psychol Health, 1996; 11, 505-25. doi: 10.1080/08870449608401986 [46] Reed YM. Predictors of Condom Use among Middle-Income, African American Women. Dissertations & Theses-Gradworks, 2015. [47] Zang C, Guida J, Sun Y, et al. Collectivism culture, HIV stigma and social network support in Anhui, China: a path analytic model. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 2014; 28, 452-8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0015 [48] Hofstede G. Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. Adm Sci, 1991; 23, 113-9. http://www.worldcat.org/title/cultures-and-organizations-software-of-the-mind-intercultural-cooperation-and-its-importance-for-survival/oclc/558675706 [49] Jansen C, Verstappen R. Fear Appeals in Health Communication: Should the Receivers' Nationality or Cultural Orientation be taken into Account? J Intercult Commun Res, 2014; 43, 346-68. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2014.981675 [50] Setegn T, Tulu B, Takele a, et al. Correlates of Risk Perception to HIV Infection, Abstinence and Condom use among Madawalabu University Students, Southeast Ethiopia: Using Health Belief Model (HBM). Global Journal of Medical Research, 2013; 13, 24-32. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267514987_Correlates_of_Risk_Perception_to_Hiv_Infection_Abstinence_and_Condom_use_among_Madawalabu_University_Students_Southeast_Ethiopia_Using_Health_Belief_Model_HBM [51] Eileen SAED, Wagstaff DA, Heckman TG, et al. Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model: Testing direct and mediated treatment effects on condom use among women in low-income housing. Ann Behav Med, 2006; 31, 70-9. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_11 [52] Huy NV, Dunne MP, Debattista J. Predictors of condom use behaviour among male street labourers in urban Vietnam using a modified Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model. Cult Health Sex, 2015; 18, 1-16. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282759712_Predictors_of_condom_use_behaviour_among_male_street_labourers_in_urban_Vietnam_using_a_modified_Information-Motivation-Behavioral_Skills_IMB_model [53] Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Vanable PA, et al. Predicting condom use among STD clinic patients using the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model. J Health Psychol, 2010; 15, 1093-02. doi: 10.1177/1359105310364174 [54] Liu Z, Wei P, Huang M, et al. Determinants of consistent condom use among college students in China: application of the information-motivation-behavior skills (IMB) model. PLoS One, 2013; 9, e108976. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266263752_Determinants_of_Consistent_Condom_Use_among_College_Students_in_China_Application_of_the_Information-Motivation-Behavior_Skills_IMB_Model/fulltext/543f733f0cf2e76f022455b8/266263752_Determinants_of_Consistent_Condom_Use_among_College_Students_in_China_Application_of_the_Information-Motivation-Behavior_Skills_IMB_Model.pdf [55] Cooper M, Loue S, Lloyd LS. Perceived susceptibility to HIV infection among Asian and Pacific Islander women in San Diego. J Health Care Poor Underserved, 2001; 12, 208-23. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0808 [56] Diiorio C, Parsons M, Lehr S, et al. Factors associated with use of safer sex practices among college freshmen. Res Nurs Health, 1993; 16, 343-50. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-240X [57] Carpenter CJ. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun, 2010; 25, 661-9. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.521906 [58] Kalichman S, Stein JA, Malow R, et al. Predicting protected sexual behavior using the Information-Motivation-Behaviour skills model among adolescent substance abusers in court-ordered treatment. Psychol Health Med, 2002; 7, 327-38. doi: 10.1080/13548500220139368 [59] White RC. Health Belief Model, condom use and Jamaican adolescents. Social & Economic Studies, 2004; 53, 155-86. [60] Buckingham R, Meister E. Condom Utilization among Female Sex Workers in Thailand: Assessing the Value of the Health Belief Model. California Journal of Health Promotion, 2003. [61] Lammers J, Van Wijnbergen S, Willebrands D. Gender Differences, HIV Risk Perception and Condom Use. Ssrn Electronic Journal, 2011; ti2011-51/2. [62] Zuo X, Lou C, Gao E, et al. Gender Differences in Adolescent Premarital Sexual Permissiveness in Three Asian Cities: Effects of Gender-Role Attitudes. J Adolesc Health, 2012; 50, S18-S25. https://jhu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/gender-differences-in-adolescent-premarital-sexual-permissiveness-5 [63] Sprecher S, Treger S, Sakaluk JK. Premarital sexual standards and sociosexuality: gender, ethnicity, and cohort differences. Arch Sex Behav, 2013; 42, 1395-405. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0145-6 [64] Graham CA, Crosby R, Yarber WL, et al. Erection loss in association with condom use among young men attending a public STI clinic: potential correlates and implications for risk behavior. Sex Health, 2006; 3, 255-60. doi: 10.1071/SH06026 [65] Traeen B, Hovland A. Games People Play: Sex, Alcohol and Condom Use among Urban Norwegians, Contemp. drug Probs. 1998; 25. doi: 10.1177/009145099802500101 [66] Sun X, Liu X, Shi Y, et al. Determinants of risky sexual behavior and condom use among college students in China. Aids Care, 2013; 25, 775-83. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.748875 [67] Kirby D, Short L, Collins J, et al. School-based programs to reduce sexual risk behaviors: a review of effectiveness. Public Health Rep, 1994; 109, 339-60. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/CRDWeb/ShowRecord.asp?ID=11994000275 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links