-

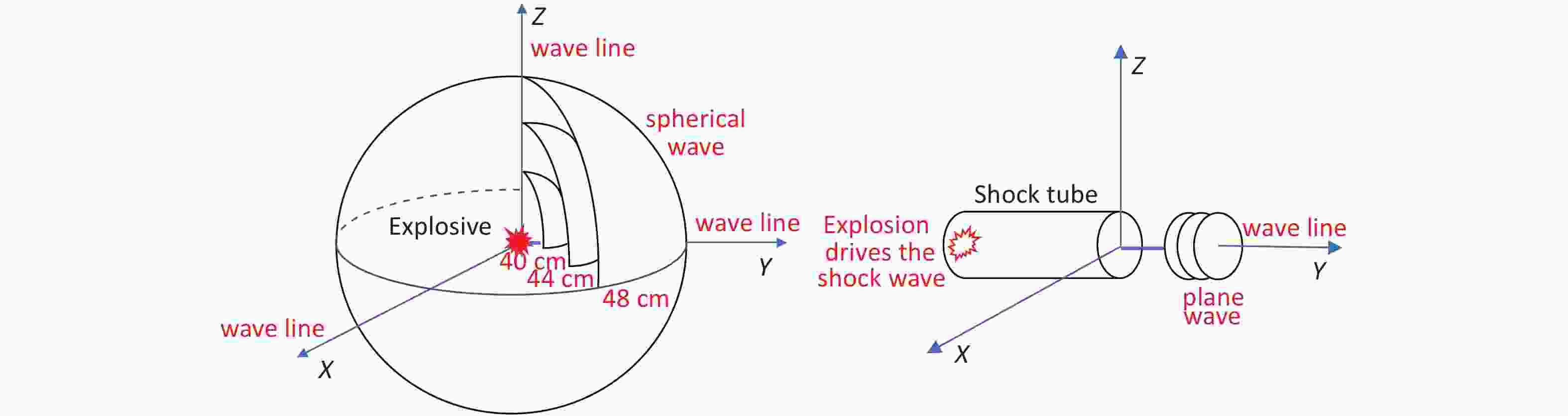

Blast injuries are the most common fatal injuries sustained during military actions, terrorist attacks, and peacetime accidents[1]. Shock waves are an important cause of injury and can cause visceral injury or even death without visible damage to the body surface. Shock waves can cause complex damage to multiple systems and organs owing to instantaneous overpressure and dynamic pressure[2], and air-filled lungs are the most vulnerable target organs. Studies have indicated that the implosion and overtension effects of shock waves lead to alveolar rupture, lung tissue hemorrhage, pulmonary interstitial damage, lung edema, and pleural effusion, which are life-threatening conditions[3]. Therefore, studying lung blast injury is of great significance for the treatment of blast injuries. Because it is difficult to fully simulate the complex environment of the real explosion site, it is necessary to establish an animal model to examine the effects of shock waves on lung tissue[4]. To study the complex pathophysiological changes caused by blast injury to the lungs, a standardized animal model must be established. The methods for establishing blast-injury animal models in China and abroad are mainly divided into two categories: bioshock tubes and open-field blasts. The physical parameters of shock waves induced by a shock tube can be artificially set, and the waves can be accurately applied to the intended injury site[5, 6]. Shock tubes are not affected by factors such as the natural environment. Therefore, shock tubes can be widely used in laboratory research[7]. However, with the shock waves induced by a bioshock tube, it is difficult to simulate the Friedlander waveform at the real explosion site[8]. An open-field blast can realistically simulate the conditions of an explosion site and reflect the explosion-related physical parameters and their interactions through the generated complex spherical-energy field. However, the disadvantage is that the stability of the experimental results is affected by the composition and yield of the explosives and the space environment. In a previous study, we used a new type of high-energy compressed explosive[9] to reproduce an open-field blast and ideally solved the problem of unstable energy parameters of explosives and foreign body injury. The objective of the present study was to investigate the effects of different overpressure peaks and overpressure impulses generated by field explosion shock waves on lung tissue hemorrhage, edema, pathology, and oxygenation index in rats and to provide an experimental basis for the prevention and treatment of blast injuries.

-

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 220–250 g were provided by Beijing Keyu Animal Center. The animals were housed in a cage with a relative humidity of 60% and an ambient temperature of 25 °C. The rats were allowed to acclimatize for one week. In this study, all the animals were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 23–85, revised 1996) and the Regulation for Laboratory Animals in the General Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army. This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army (2017-X13-68).

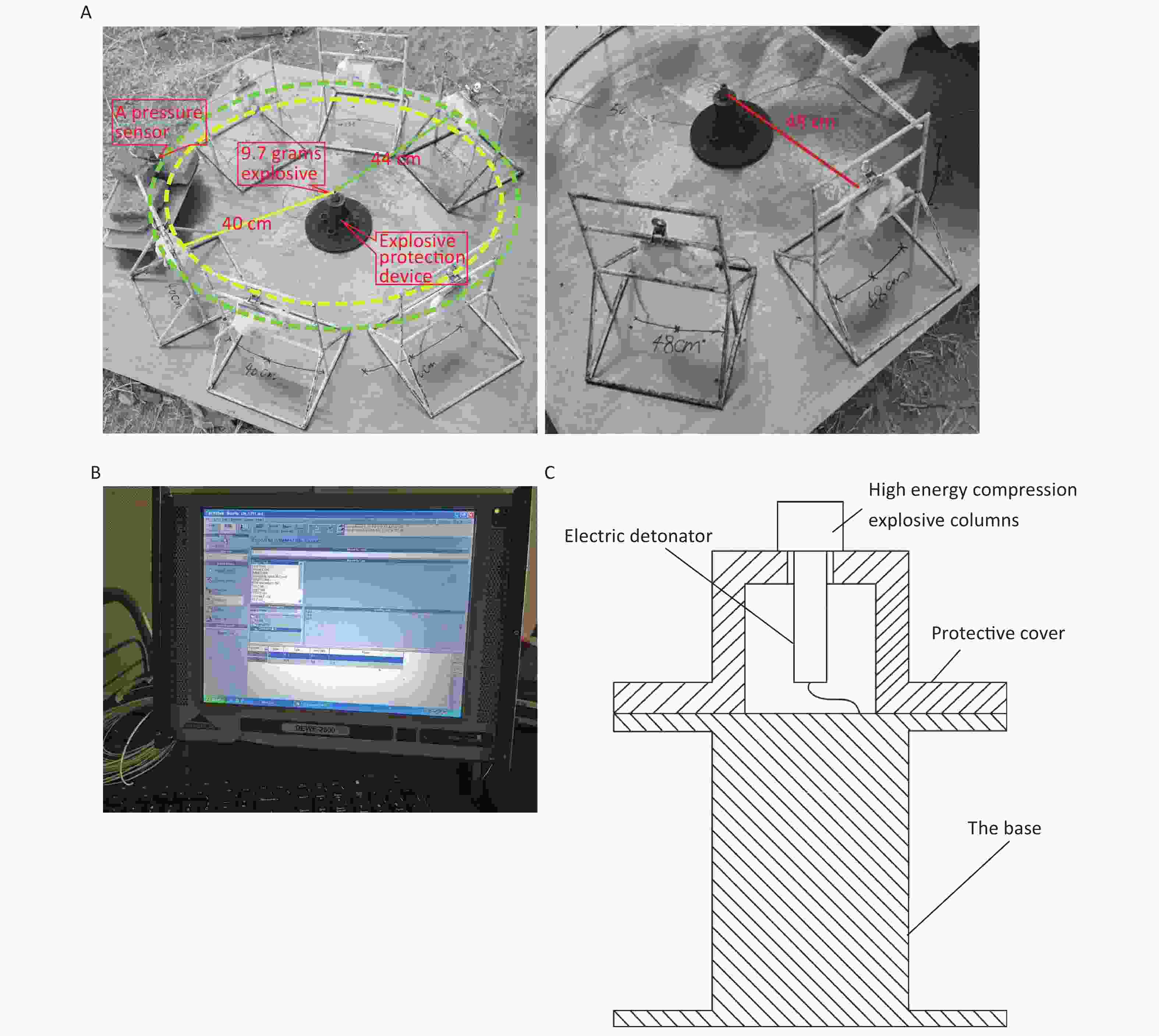

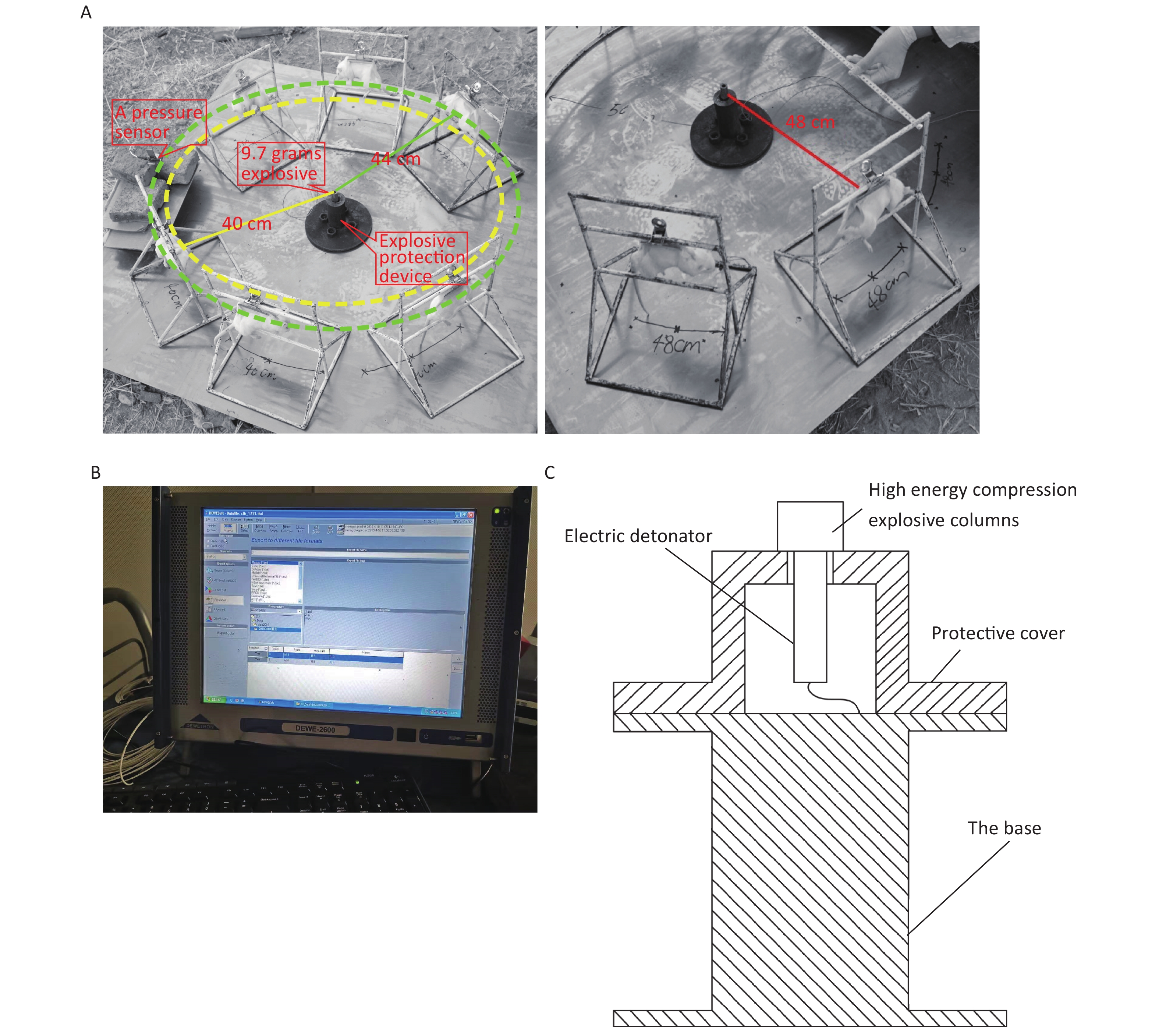

The 144 rats were randomly divided into the following four groups using the random number table method: the 40 cm group, 44 cm group, 48 cm group, and sham-injured control group. There were 36 rats in each group. Examinations were performed 0, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 168 h after injury. The rats were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection with 3% pentobarbital (45 mg/kg), and the shock-wave injuries were induced in batches (Figure 1A). The explosive device consisted of an explosive source, an electric detonator, a protective cover, and a base (Figure 1C). After the data-acquisition system was debugged, the detonator was activated to perform blasting and record the physical parameters of the explosion. After the blast, the general vital signs of the rats and deaths were recorded. The rats started to wake up after approximately 2 h and began to drink freely in 4–6 h. For the sham-injured control group, the rats were placed 100 m from the explosion center and were shielded from the shock wave. The other treatments were identical to those for the injured groups. The testing site, instruments, and equipment used for the study were provided by the Key Laboratory of Transient Impact Technology at the China South Industries Group Corporation.

Figure 1. Simulated open-field blast site setup. (A) 9.7 g high-energy compression explosive columns (9.7 g; 70% hexogen and 30% aluminum powder; explosive energy equivalent to 15–17 g of trinitrotoluene) were fixed to the explosive protection device. A toothless clip was used to hold the medial skin of each rat’s back along the spine to hang the rat on a supporting holder. The animal was maintained without direct contact with the holder. The rats were placed around the explosive column at distances of 40 cm (6 pieces/ring), 44 cm (6 pieces/ring), and 48 cm (8 pieces/ring) from the center of the explosion, and the left chest wall faced the source of the explosion. The distance between the two supporting holders was 1 cm, and the pressure sensor (113A21, PCB company) was placed parallel to the holder in the middle. (B) The signals were digitized by a 16-channel data acquisition and processing system (DWE-2600, Austria) after a signal adapter (amplifier) was applied. Then, the peak overpressure, impulse, and positive pressure time of the shock waves were recorded and analyzed. (C) Schematic of the explosive protection device.

-

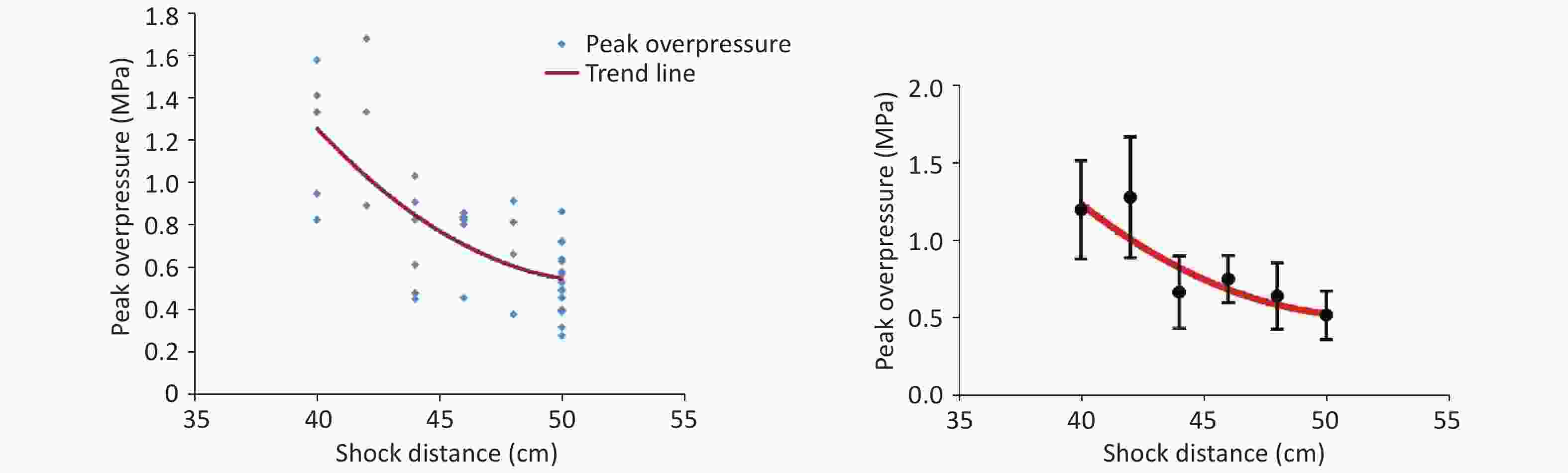

The shock-wave waveform curves for 42 effective explosion experiments (six groups at distances of 40, 42, 44, 46, 48, and 50 cm from the explosion center) were tested in real time. The obtained pressure measurement data were fitted and analyzed to obtain the fitting distribution of the overpressure peak data in the range of 40–50 cm (Figure 2, Table 1). Within this range, the overpressure peak, overpressure impulse, and positive pressure time of the shock wave in the animal experiments involving the 40, 44, and 48-cm groups were selected for detection (Figure 1).

Table 1. Fitted data of the peak overpressure of shock waves at different distances

Distance (cm) Peak overpressure (MPa) 40 1.22 ± 0.32c,d,e,f 42 1.30 ± 0.39c,d,e,f 44 0.69 ± 0.24a,b 46 0.77 ± 0.15a,b,f 48 0.66 ± 0.22a,b 50 0.54 ± 0.16a,b,d Note. Other distances vs. the 40-cm group, aP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 42-cm group, bP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 44-cm group, cP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 46-cm group, dP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 48-cm group, eP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 50-cm group, fP < 0.01. Significant differences in peak overpressure were observed among the six groups (P < 0.05, F = 12.105). -

Each anesthetized rat was placed in the supine position on an animal operating table, and the abdominal cavity was opened in the middle of the abdomen to expose the abdominal aorta. Blood samples were collected using anticoagulated blood collection tubes, and the rats were sacrificed via exsanguination. The trachea in the neck was sharply separated and ligated. The thoracic cavity was opened in the middle to observe the lung injury and bleeding. The entire lung along the posterior part of the trachea was sharply separated and photographed. The left lung was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde buffer, and the histological changes were observed via hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in a mid-sagittal section of the lung tissue.

-

The third lobe of the right lung was sharply separated along the right bronchus and absorbed water with a filter paper. This lung lobe was weighed using an electronic analytical balance (Shanghai Tianping Instrument Factory, China) to determine the wet weight and then dried in an oven at 60 °C for 72 h. The dry weight was determined, and the wet/dry weight ratio was calculated and recorded.

-

The hemoglobin (Hb) concentration of the collected blood was measured using a fully automatic analyzer (Xi-20, Sysmex Corporation, Japan) to evaluate the blood loss. A portable blood gas analyzer (OPTI Medical Systems, USA) was used to measure the pH, partial pressure of oxygen (PO2), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2), and lactic acid (Lac) in the arterial blood. The lung function was assessed according to the diagnostic criteria for acute lung injury (ALI) and the diagnostic criteria for primary organ dysfunction in animal models proposed by Hu et al.[10].

-

According to the criteria for the pathological Smith score[11, 12], 3–5 pathologists scored the H&E-stained lung tissues, and the average scores were recorded. The tissues were scored on a scale of 0–4 points (0 points corresponding to no injury, 1 point for 0%–25% injury, 2 points for 25%–50% injury, 3 points for 50%–75% injury, and 4 points for > 75% injury). The alveolar and interstitial inflammation, hemorrhage, edema, atelectasis, and necrosis were scored separately. The maximum score was 28 points.

-

A statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS 21.0 and Excel V2019. The continuous variables were expressed as

$ \bar x \pm s $ , and the differences were compared via t tests. A factorial design was employed, and an analysis of variance was performed to compare the blood loss, blood gas parameters, and pathological scores among the animal models. A least significant difference test was performed for pairwise comparisons. Scatter plots of the peak overpressure and overpressure impulse were drawn using Excel and fitted by a linear line to determine the shock-wave loading trend. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to evaluate the survival rates of the experimental animals, and a logarithmic survival curve was plotted. The χ2 test was used to compare the survival rates among the 40, 44, and 48 cm groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all the statistical tests were two-tailed tests. -

Limited by the instability of the explosive and environmental factors, the shock-wave peak overpressure of the 9.7-g high-energy compression explosive column differed in every explosion experiment. After the fitting of the data (Figure 2), the relationship between the obtained peak overpressure impulse was determined, as shown in Table 1. According to the fitted data for the 40- to 50-cm groups, the peak overpressure was attenuated from 1.22 ± 0.32 MPa to 0.54 ± 0.16 MPa (Table 1).

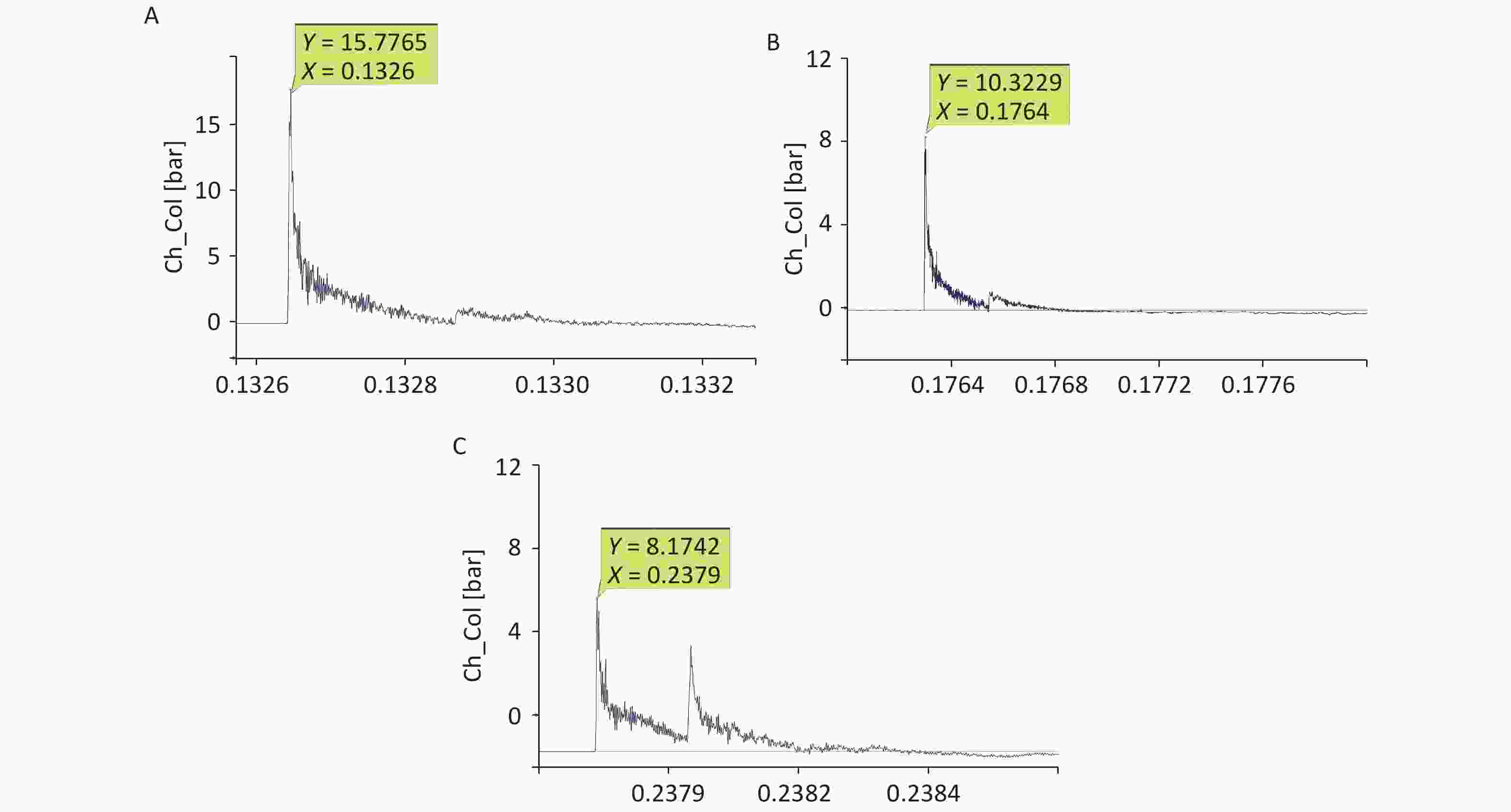

For the 40-cm group, the shock-wave pressure increased significantly after the detonation, with a steep rise curve, a short action time in the positive pressure zone, and double peaks for ground reflection. The peak pressure fluctuated slightly, the overpressure was 1–1.6 MPa, and the duration was 200–230 µs. The impulse and positive pressure durations were relatively stable, and the reflected peaks lasted between 380 and 450 µs. For the 44-cm group, the overall waveform interference was small; ground reflection existed but was not strong, and the double-peak ground reflection was more obvious. Compared with the corresponding values for the 40-cm group, the overpressure was lower, the attenuation time was longer, and the impulse value was lower. For the 48-cm group, ground reflection existed, the double-peak ground reflection was significantly overlapped, and the double-peak reflection increased the impulse. Compared with the corresponding values for the 44-cm group, the overpressure value was lower, the attenuation time was longer, and the impulse value was lower (Figure 3, Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of the shock-wave peak overpressure, impulse induced, and positive pressure duration at different distances

Group (cm) Peak overpressure (MPa) Impulse

(Pa·s)Positive pressure duration (µs) 40 1.34 ± 0.03b,c 44.66 ± 3.74a 435.50 ± 83.24 44 0.75 ± 0.12b 37.41 ± 3.68a 494.75 ± 23.00 48 0.69 ± 0.03c 39.31 ± 2.98 488.00 ± 58.36 Note. 40-cm group vs. 44-cm group, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01; 40-cm group vs. 48-cm group, cP < 0.01. Significant differences in overpressure were observed among the three groups (P < 0.05, F = 96.302). Significant differences in impulses were observed among the three groups (P < 0.05, F = 4.645). -

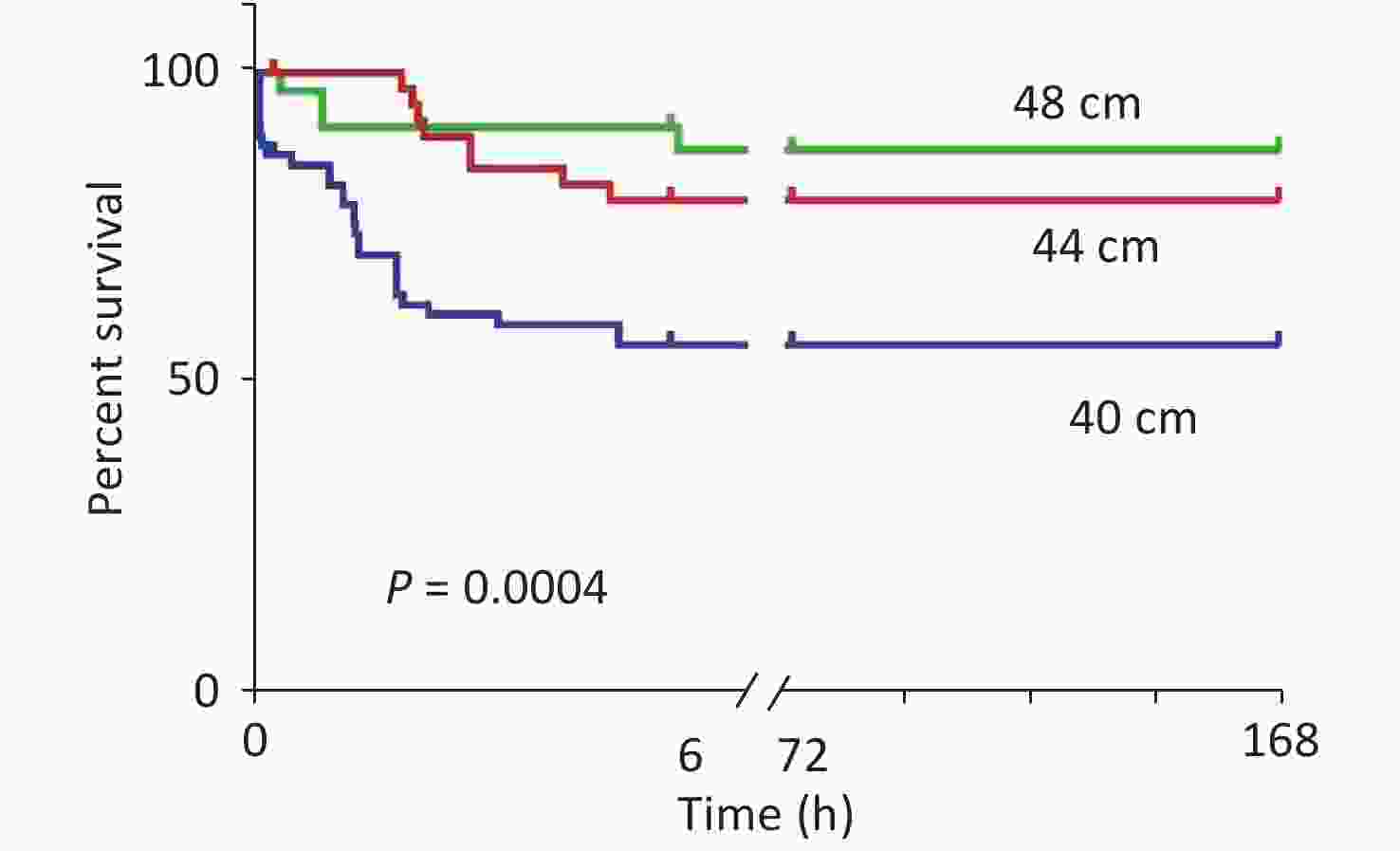

After the blast injuries, 18 rats in the 40 cm group had shallow and fast breathing and slight heartbeats. Ten of them died immediately (of which four had bleeding in the left eye). The anatomy exhibited lung tissue hemorrhage, liver congestion, and swelling. In the 44 cm group, eight rats had shallow and fast breathing. In the 48 cm group, three rats had shallow and fast breathing. The anatomy exhibited no rib fractures, intestinal cavity damage, or thoracoabdominal cavity injuries in the three groups of rats. The mortality rates of the rats with blast injuries at different distances were as follows: 41.2% for the 40 cm group, 17.8% for the 44 cm group, and 10% for the 48 cm group (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Survival analysis of the animals with blast injuries at different distances. The survival rates for the 40-, 44-, and 48-cm groups were 58.8%, 82.2%, and 90.0%, respectively, and the differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 29.249, P < 0.001). Death of the experimental animals occurred within 24 h.

-

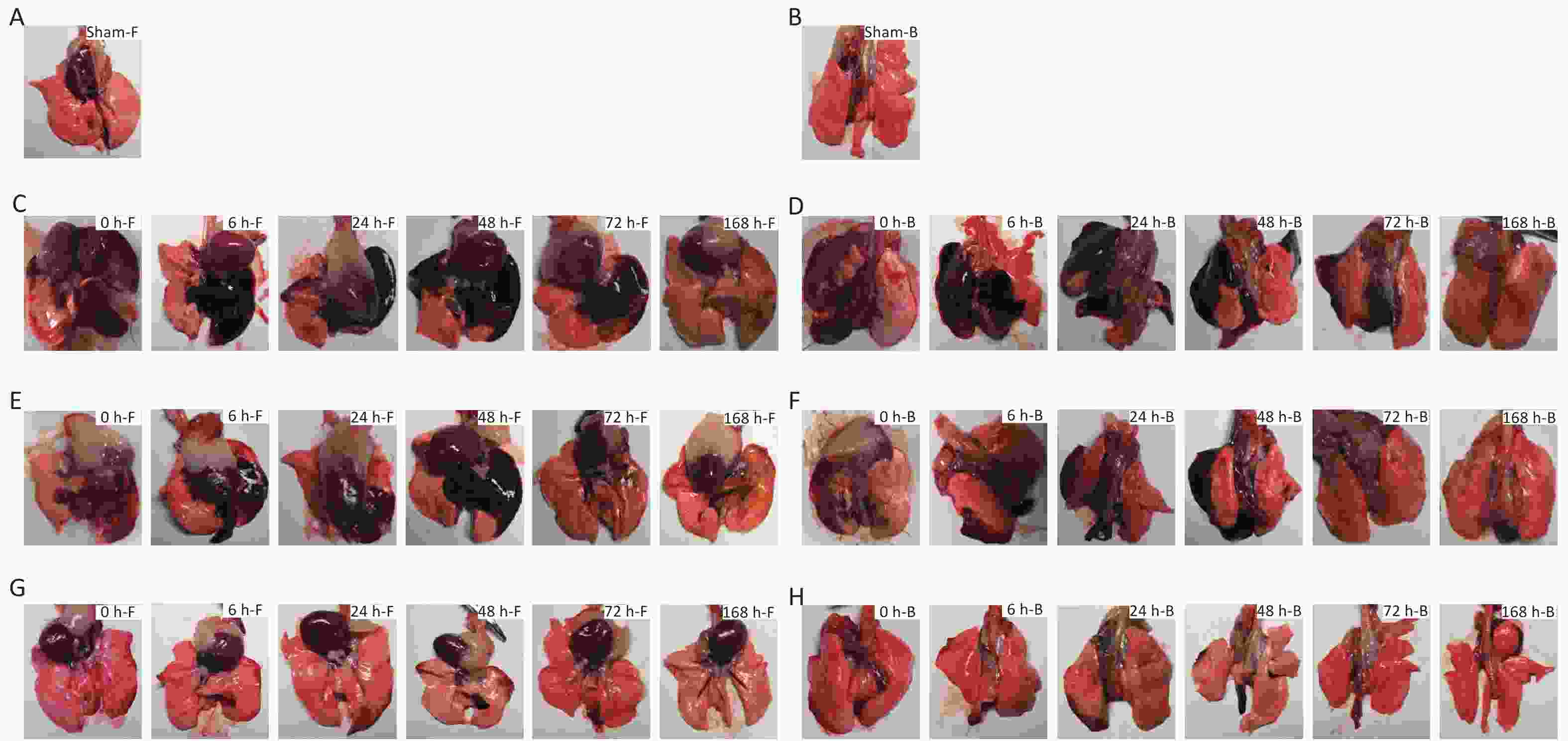

Compared with the sham-injured control group, for the 40 cm group, large hemorrhagic lesions formed in the left, middle, medial, and lower right lungs, with scattered patches of hemorrhagic lesions on the lateral edge of the right lung, and the hemorrhagic lesions appeared dark red. For the 44 cm group, large patches of hemorrhage were observed in the left lateral and middle lung, small patches of hemorrhage were observed in the right lower lobe, and the hemorrhagic sites appeared dark red. For the 48 cm group, multiple scattered hemorrhagic foci were observed in the lateral margin of the lung and the right lower lobe, but no significant changes were observed in the right upper lobe, and the hemorrhagic sites appeared light red. For the 40 and 44 cm groups, no significant changes were observed in the range of hemorrhagic lesions for 24 h after injury. The color of the hemorrhagic lesions gradually became dark. Starting at 48 h after injury, the range of the hemorrhagic lesions gradually decreased, and the color of the lesion edge became lighter. The color of the hemorrhagic foci turned yellow-brown for both groups 168 h after injury. For the 48 cm group, the hemorrhage range gradually decreased, and the edge turned yellow-brown 24 h after injury. The left and right lungs were essentially normal approximately 168 h after injury (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Macroscopic gross anatomy observations of the rats suffering from blast injuries. (A) front view for the sham-injured control group; (B) back view for the sham-injured control group; (C) front view for the 40-cm group; (D) back view for the 40-cm group; (E) front view for the 44-cm group; (F) back view for the 44-cm group; (G) front view for the 48-cm group; (H) back view for the 48-cm group. Number of rats (n) = 6.

-

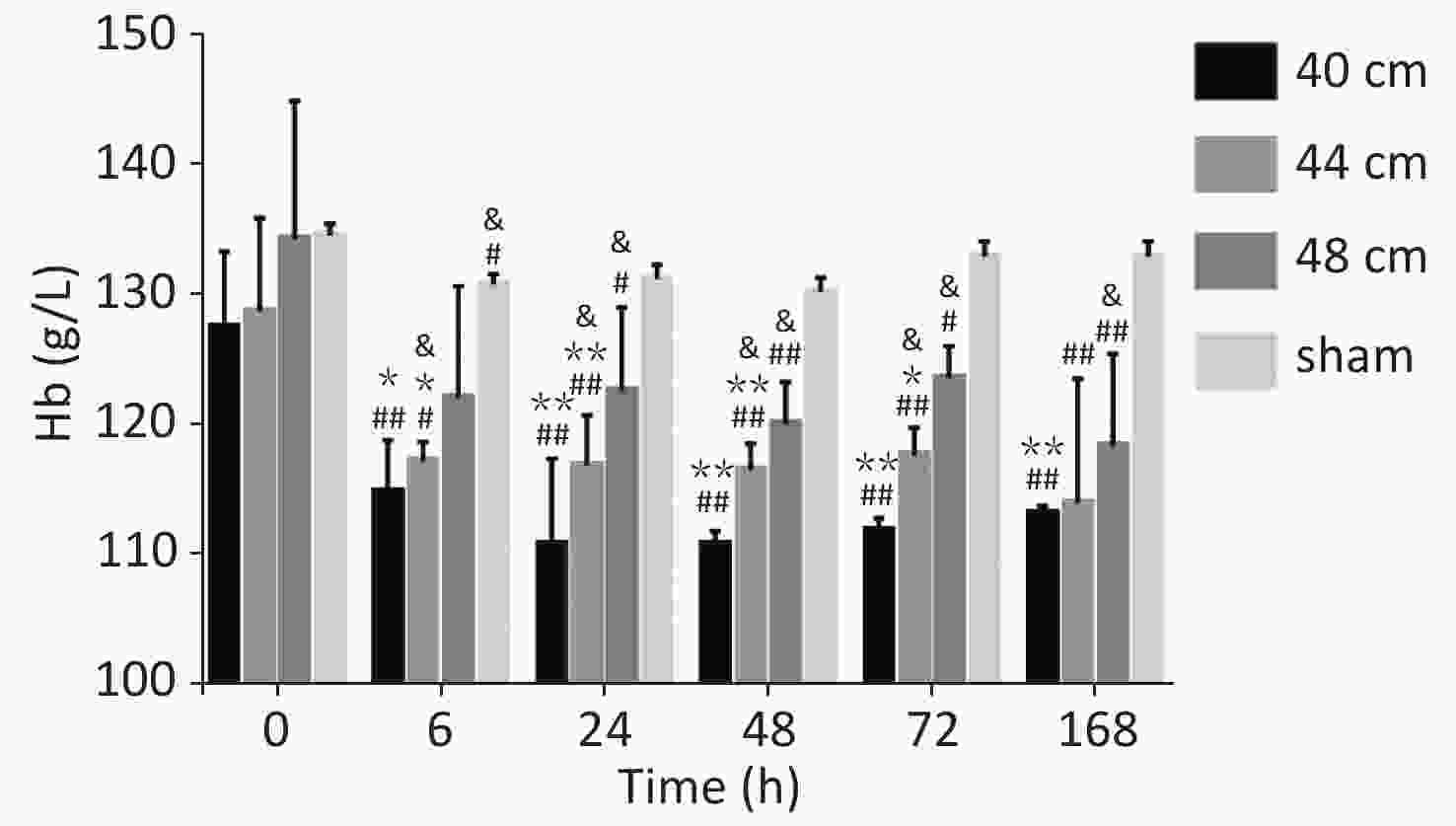

Significant differences in the blood Hb content were observed between the 40, 44, and 48 cm groups (P < 0.01) and the sham group. The Hb level decreased gradually with the decreasing distance from the blast. The lowest Hb level was observed for the 40 cm group, and the highest Hb level was observed for the control group. Significant differences in the blood Hb content were observed between 0 h and the other time points (P < 0.05) for the 40 and 44 cm groups. No difference in the blood Hb content was observed between the time points (P > 0.05) for the 48 cm group (Figure 6).

-

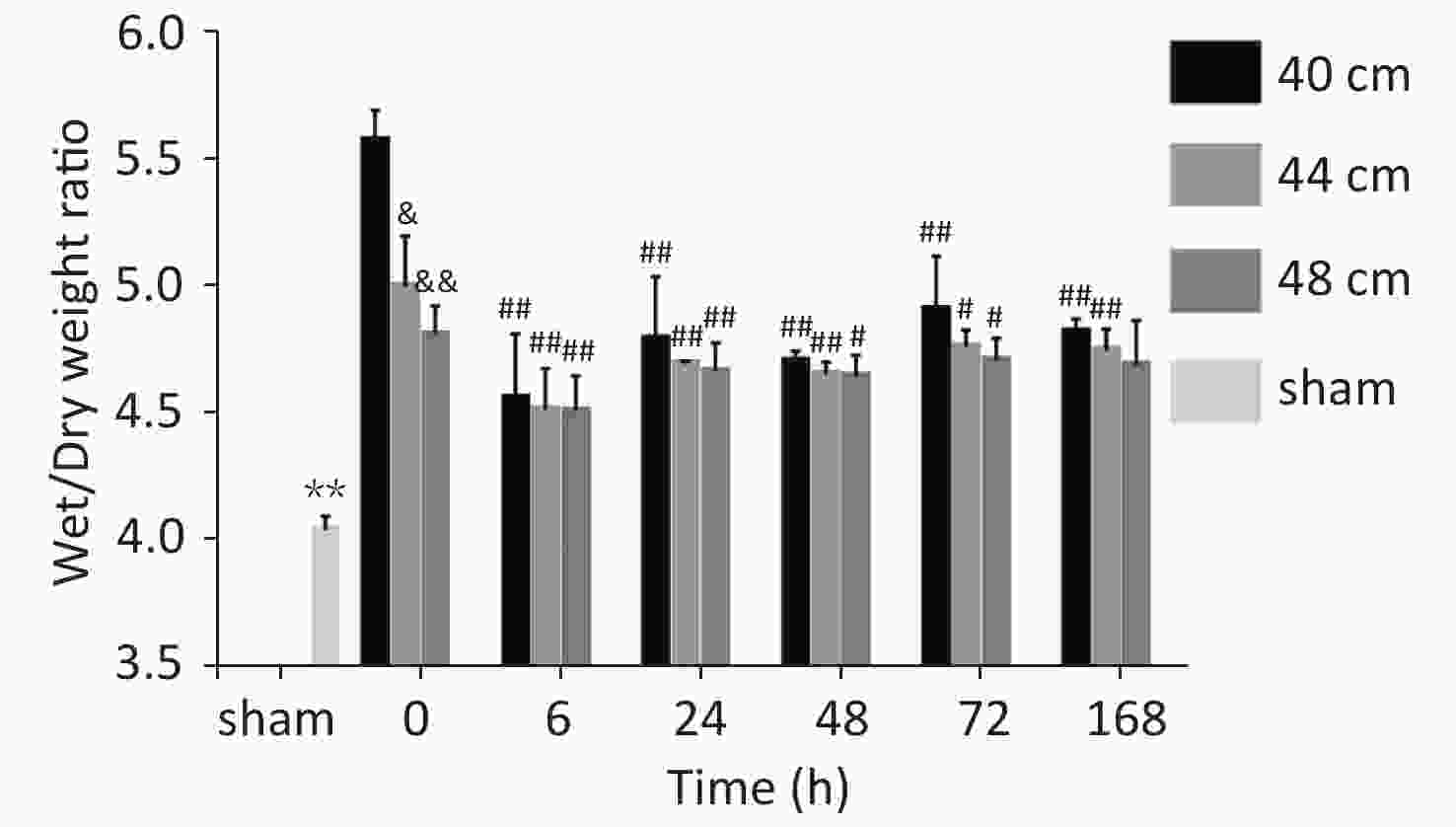

Significant differences in the wet/dry weight ratio were observed between the 40, 44, and 48 cm groups and the sham group (P < 0.01). The wet/dry weight ratio gradually increased with the decreasing distance. The highest ratio was observed for the 40 cm group, and the lowest ratio was observed for the sham group. The wet/dry weight ratios of the lung for the 40 cm group were significantly higher than those for the 44 and 48 cm groups 0, 48, 72, and 168 h after injury (P < 0.05) (Figure 7).

-

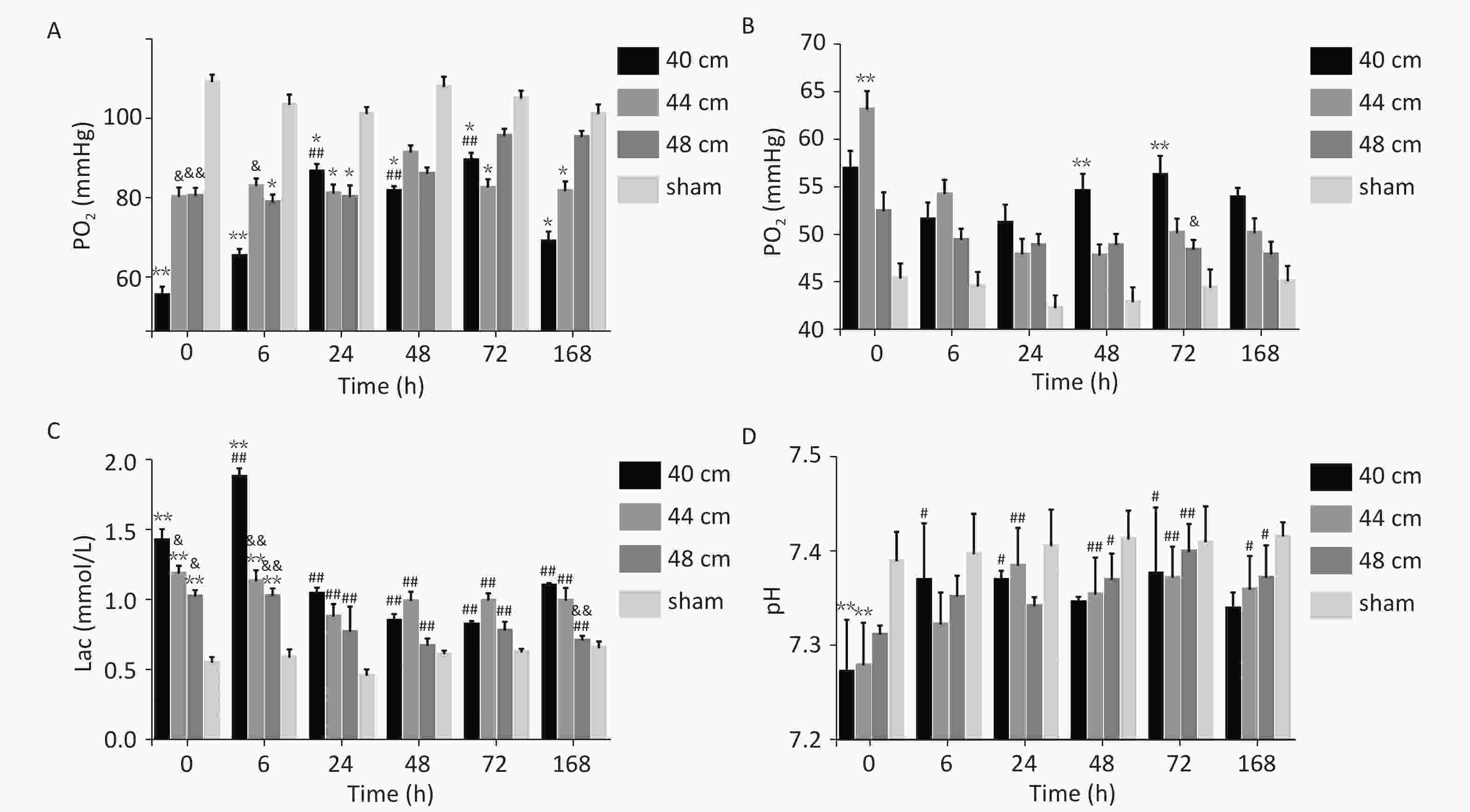

For the 40, 44, and 48 cm groups, the arterial blood PO2, PCO2, Lac, and pH values at six time points were significantly different from those in the sham group (P < 0.01). Time and distance had an interactive effect on the blood PO2 in the animals with lung injuries. Immediately (0 h) after injury, the blood PO2 was significantly lower for the 40 cm group than for the other groups (P < 0.01). 0 and 6 h after injury, the blood PCO2 was higher for the 40 and 44 cm groups than for the 48 cm group. At the other time points, the blood PCO2 was highest for the 40 cm group. From 0 to 24 h after injury, the blood Lac gradually increased with the decreasing distance (Figure 8).

-

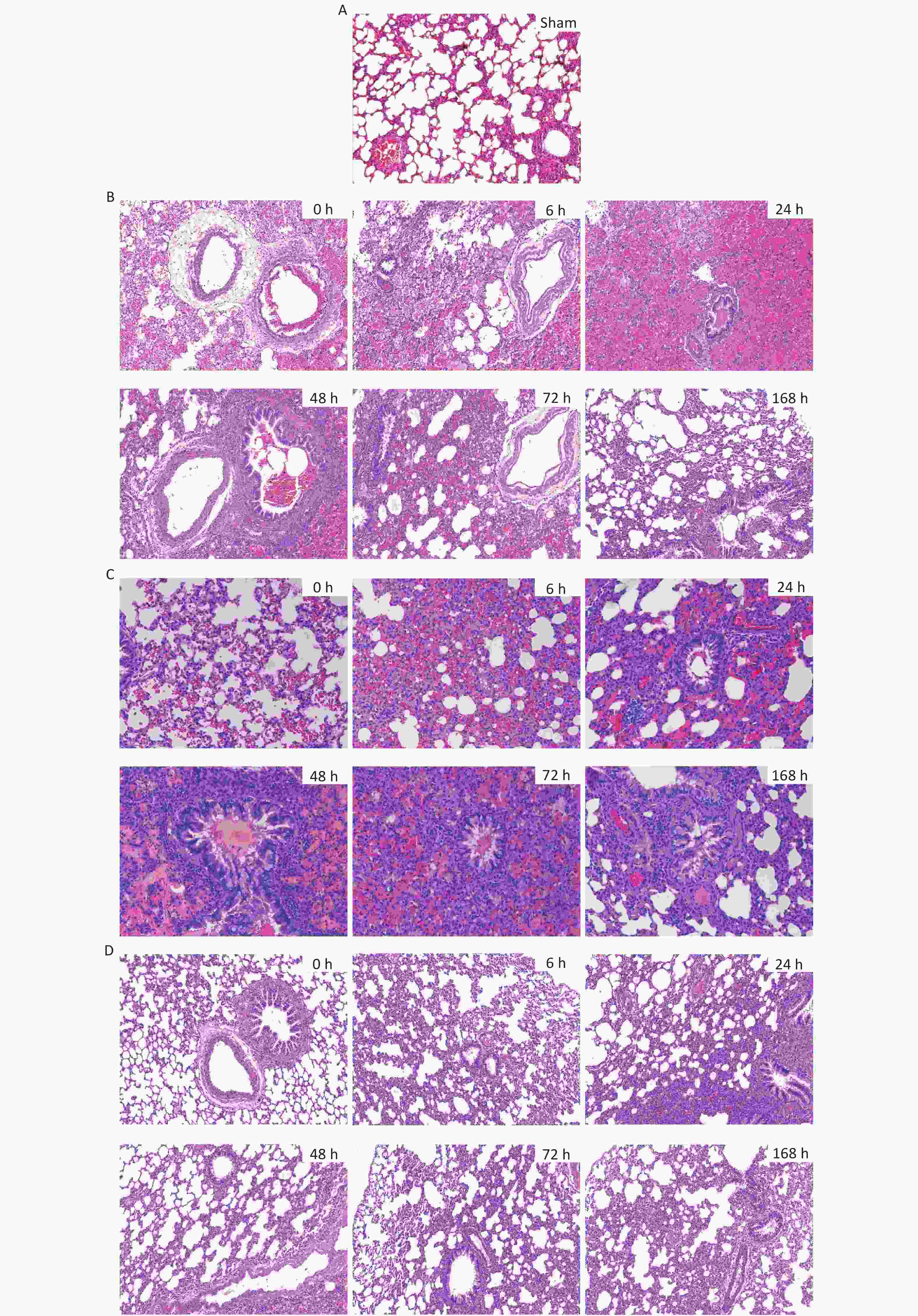

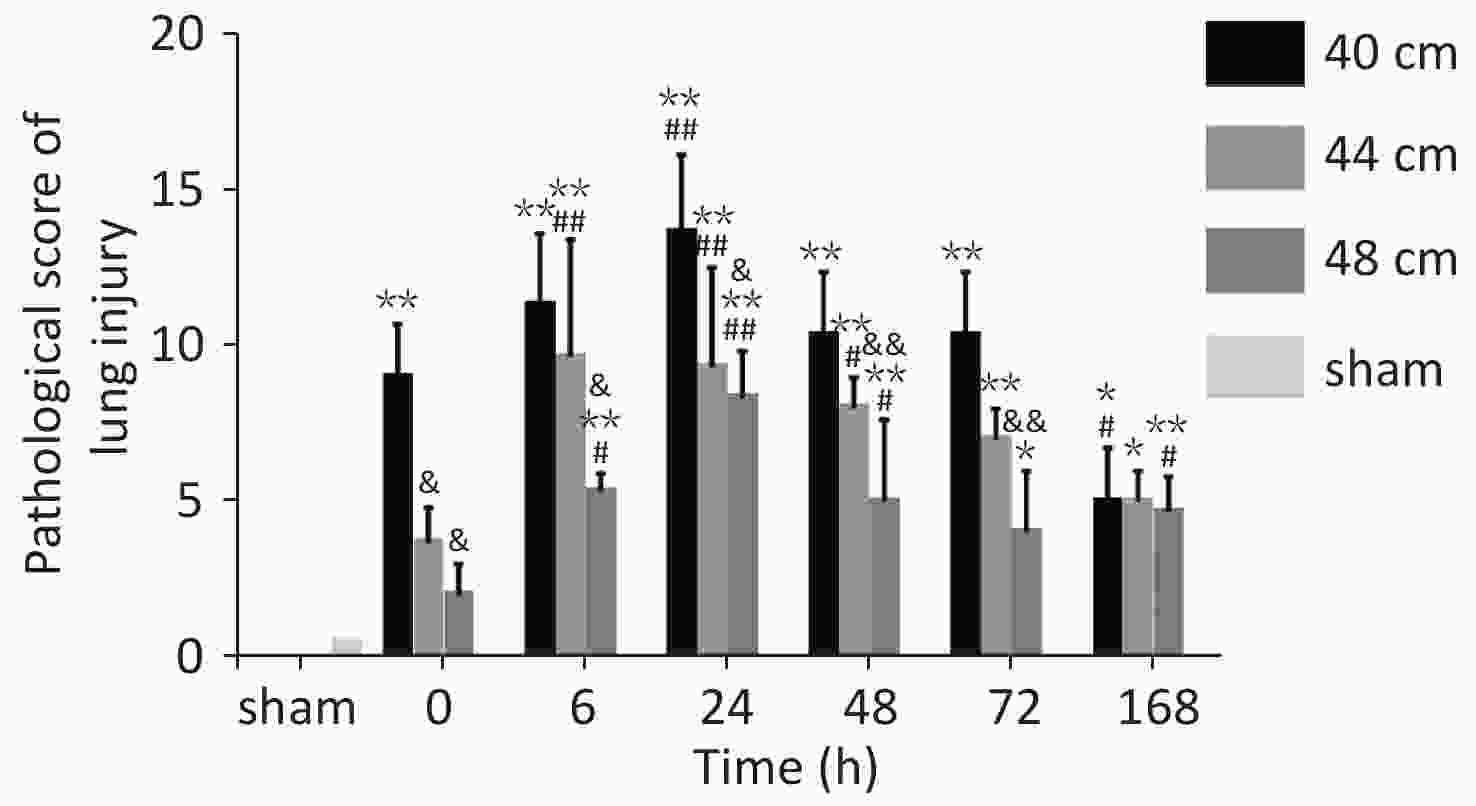

For the 40 cm group, alveolar epithelial rupture and fusion, alveolar septal necrosis, and massive patchy hemorrhages in the alveoli were observed immediately (0 h) after injury. Exudate was present in the alveolar cavity at 6 h. The alveolar hemorrhage and exudation were most pronounced at 24 h and then gradually improved. 48 h after injury, 'sleeve-like' edema was observed, and the alveolar septum was significantly thickened. Alveolar collapse and atelectasis were most obvious at 72 h and were improved 168 h after injury. For the 44 cm group, alveolar focal hemorrhage was observed immediately (0 h) after injury. Hemorrhages were most severe at 6 h and then gradually improved. The edema exudate in the alveoli was most obvious at 48 h and lasted until 72 h. Alveolar collapse and atelectasis appeared 6 h after injury and then improved slightly. For the 48 cm group, mild injury occurred without obvious hemorrhage and exudate in the alveolar space and lung interstitium. Alveolar septal thickening and partial alveolar cavity collapse were observed. These changes were most obvious at 24 h and then gradually improved. Compared with the sham group, consolidation in the lungs was evident at 24 h (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9. H&E staining and pathological scores of lung tissues in the rats with blast injuries (magnification: ×200). (A) sham group; (B) 40 cm group; (C) 44 cm group; (D) 48 cm group. Number of rats (n) = 6.

Figure 10. Pathological scores for lung tissues in rats with blast injuries. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. sham group; &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01 vs. 40-cm groups; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. 0 h; Number of rats (n) = 6.

The pathological Smith scores (H&E staining) for lung injury for the rats in the 40, 44, and 48 cm groups were significantly different from those for the sham group (P < 0.01). The pathological scores were negatively correlated with the distance from the blast. The score immediately (0 h) after injury was significantly higher for the 40 cm group than for the sham group (P < 0.01) but was significantly lower than that 24 h after injury (P < 0.01). The score immediately (0 h) after injury was significantly lower than those at 6, 24, and 48 h for both the 44 and 48 cm groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 11).

-

The incidence of blast injury has been increasing during both peacetime and wartime. Blast injury is a hotspot and presents challenges for the military and in disaster medicine[13]. This study focused on the impact of a simple primary explosion[7, 14, 15]. Shock waves can cause lung damage, which may lead to a variety of pathophysiological changes[16], including hemorrhage, edema, and hypoxia. In the experiment, to simulate the injuries at a real explosion site, a new type of explosive device (patent number: 201020597622.4) developed by the authors’ department unit[17] was adopted, and a compression explosive column was used as the source of the open-field explosion to eliminate shrapnel, sand, stone and other direct damage. This is because the compression explosive column (hexogen and aluminum powder, dose of 9.7 g/column) had fewer impurities than before[9]. A toothless clip was used to hold the medial skin of each rat’s back along the spine to hang the rat on a supporting holder. This prevented falling injury and collision injury caused by rats flying out, ensuring that the injury was entirely caused by the blast wave. By testing the output characteristics of the shock-wave waveform curve of 42 effective explosion experiments in the range of 40–50 cm from the explosion center and analyzing the pressure fitting data, a significant difference between the 44 cm overpressure peak and the 40-cm overpressure peak was observed, while there was no difference in the overpressure peaks of the four groups in the range of 44–50 cm. Therefore, 48 cm, which was also 4 cm apart, was selected for animal experiments. We analyzed the gross anatomy of the lungs, pulmonary hemorrhage, edema, blood gas, and tissue pathology changes.

-

With the open-field explosion, the peak overpressure, the impulse, and the positive pressure induced by the shock waves were positively correlated with the explosive yield[9]. The peak overpressure increases rapidly after an explosion and then slowly decreases. The duration of the continuous positive pressure is approximately 400 µs. With shock-tube technology, overpressure is achieved by gradually increasing the pressure of the air pump. Therefore, the peak value slowly increases and then slowly decreases. The duration of the continuous positive pressure can reach 200 ms[18], which is 500 times longer than that for an open-field explosion. Although researchers have aimed to simulate the Friedland waveform of a real explosion by improving the mechanical design of a shock tube or changing the fuel composition[4], causing the peak pressure to reach the intensity of an open-field explosion is always difficult. Therefore, injury can only be obtained by extending the duration of the shock[19, 20], but this causes more severe injuries and higher death rates than the open-field explosion, which differs from the real explosion shock mechanism encountered during peacetime and wartime. The measured energy of the 9.7 g compression explosive column is equivalent to that of 15–17 g of TNT. Measuring the peak overpressure and impulse of the shock wave over six sets of distances in the range of 40–50 cm revealed that the energy attenuation of the simulated open-field shock wave was different from that of the shock tubes. The shock wave of the shock tubes exhibited linear planar propagation; thus, the energy was uniaxial attenuation in a one-dimensional direction. In contrast, the shock wave generated by the open-field explosion exhibited spherical distribution attenuation in the three-dimensional space (Figure 11). The source of the explosion is attenuated rapidly at short distances, whereas at a distance, it gradually is attenuated in the solid volume with a spherical radius[21, 22].

-

We compared the lung anatomy, Hb levels, and histopathological findings for the rats with blast injuries among the 40, 44, and 48 cm groups. The largest lung injury area (the entire left lung) and the most serious bleeding were observed for the 40 cm group. The smallest lesion area (the lateral edge of the left lung) and the least bleeding were observed for the 48 cm group. With regard to the injury degree (involving the lateral and medial zones of the left lung) and the amount of bleeding, the results for the 44 cm group were between those of the other two groups. Blast injuries can cause dilation of the alveoli and capillary vessels and alveolar wall and septal rupture and leakage[23, 24], which is a direct cause of death. With the increasing peak overpressure, the incidence and severity of lung injuries are increased and aggravated[25, 26], which may explain why many patients treated in our hospital for burns and blasts have similar burn areas and depths, but their injuries are completely different, indicating that the outcomes of the same explosion vary due to different shock-wave distances[27, 28]. On the basis of a previous study on lung injury classification[29, 30], we designed an injury index for rats with blast lung injuries: severe injury can be sustained at a 40 cm distance, moderate injury can be sustained at a 44 cm distance, and mild injury can be sustained at a 48 cm distance.

We also examined the changes in the lung wet/dry weight ratio and lung function after lung injury and found that severe lung injury was associated with the most severe hemorrhage or edema. The sustained damage peaked within 6 h after injury, which is similar to the results for scalded rats with ALI reported by Du et al.[31]. Pulmonary function results indicated that the PO2 decreased to 57 mmHg after severe lung injury. Meanwhile, the pH decreased and the PCO2 increased, indicating that carbon dioxide accumulated in the body, which may have been caused by upper-airway obstruction, insufficient alveolar ventilation, and reduced respiratory function, resulting in respiratory acidosis. After comprehensively referring to the diagnostic criteria for ALI[32, 33] and the diagnostic criteria for primary organ dysfunction in animal models proposed by Hu et al.[10], Wang et al.[34], the severe blast lung injury was found to be consistent with the diagnosis of acute pulmonary insufficiency, while the other groups exhibited no respiratory insufficiency. Therefore, for the three groups of rats with lung injury, only severe blast injuries resulted in immediate death, indicating that respiratory dysfunction is the main cause of the high mortality associated with severe blast injuries.

To simulate the injury induced by the shock wave of an open-field explosion, we performed experimental improvements for stabilizing the explosive charge and protecting against foreign-object ejection damage. However, the effects of natural environmental factors such as the ambient temperature, wind speed, and humidity on animal experiments are difficult to fully control; there was still a difference in the overpressure peak of the voltage output. It is expected that biomechanical parameters that more closely match the real explosion site can be obtained by increasing the effective explosion experiment sample size, using accurate pressure measurement data, and reducing the error of the fitting curve.

-

By simulating a shock wave in an open field in the wild, the changes in the physical parameters caused by an explosion at different distances were analyzed, and the impact of shock biomechanical effects on the severity of animal lung injuries was examined. The results provide an experimental basis for studying the prevention and treatment of blast wave-induced acute lung injuries.

-

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author on upon reasonable request.

-

The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the PLA General Hospital Ethics Committee.

-

LIU Wei and CHAI Jia Ke designed the experiments; LIU Wei, HAN Shao Fang, WANG Xiao Teng, QIN Bin, JIANG Shuai, BAI Hai Liang, LIU Ling Ying, CHANG Yang, YUE Xiao Tong, WU Yu Shou, ZHANG Zi Hao, and TANG Lang carried out the experiments; HAN Shao Fang analyzed the experimental results. WANG Xiao Teng, QIN Bin, and JIANG Shuai analyzed the data and conducted validation. BAI Hai Liang prepared figures and tables. LIU Wei was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

doi: 10.3967/bes2020.046

-

Abstract:

Objective To observe the dynamic impacts of shock waves on the severity of lung injury in rats with different injury distances. Methods Simulate open-field shock waves; detect the biomechanical effects of explosion sources at distances of 40, 44, and 48 cm from rats; and examine the changes in the gross anatomy of the lungs, lung wet/dry weight ratio, hemoglobin concentration, blood gas analysis, and pathology. Results Biomechanical parameters such as the overpressure peak and impulse were gradually attenuated with an increase in the injury distance. The lung tissue hemorrhage, edema, oxygenation index, and pathology changed more significantly for the 40 cm group than for the 44 and 48 cm groups. The overpressure peak and impulse were significantly higher for the 40 cm group than for the 44 and 48 cm groups (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). The animal mortality was significantly higher for the 40 cm group than for the other two groups (41.2% vs. 17.8% and 10.0%, P < 0.05). The healing time of injured lung tissues for the 40 cm group was longer than those for the 44 and 48 cm groups. Conclusions The effects of simulated open-field shock waves on the severity of lung injuries in rats were correlated with the injury distances, the peak overpressure, and the overpressure impulse. -

Key words:

- Shock wave /

- Animal model /

- Open-field blast /

- Lung injury /

- Biomechanical effect

-

Figure 1. Simulated open-field blast site setup. (A) 9.7 g high-energy compression explosive columns (9.7 g; 70% hexogen and 30% aluminum powder; explosive energy equivalent to 15–17 g of trinitrotoluene) were fixed to the explosive protection device. A toothless clip was used to hold the medial skin of each rat’s back along the spine to hang the rat on a supporting holder. The animal was maintained without direct contact with the holder. The rats were placed around the explosive column at distances of 40 cm (6 pieces/ring), 44 cm (6 pieces/ring), and 48 cm (8 pieces/ring) from the center of the explosion, and the left chest wall faced the source of the explosion. The distance between the two supporting holders was 1 cm, and the pressure sensor (113A21, PCB company) was placed parallel to the holder in the middle. (B) The signals were digitized by a 16-channel data acquisition and processing system (DWE-2600, Austria) after a signal adapter (amplifier) was applied. Then, the peak overpressure, impulse, and positive pressure time of the shock waves were recorded and analyzed. (C) Schematic of the explosive protection device.

Figure 4. Survival analysis of the animals with blast injuries at different distances. The survival rates for the 40-, 44-, and 48-cm groups were 58.8%, 82.2%, and 90.0%, respectively, and the differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 29.249, P < 0.001). Death of the experimental animals occurred within 24 h.

Figure 5. Macroscopic gross anatomy observations of the rats suffering from blast injuries. (A) front view for the sham-injured control group; (B) back view for the sham-injured control group; (C) front view for the 40-cm group; (D) back view for the 40-cm group; (E) front view for the 44-cm group; (F) back view for the 44-cm group; (G) front view for the 48-cm group; (H) back view for the 48-cm group. Number of rats (n) = 6.

Table 1. Fitted data of the peak overpressure of shock waves at different distances

Distance (cm) Peak overpressure (MPa) 40 1.22 ± 0.32c,d,e,f 42 1.30 ± 0.39c,d,e,f 44 0.69 ± 0.24a,b 46 0.77 ± 0.15a,b,f 48 0.66 ± 0.22a,b 50 0.54 ± 0.16a,b,d Note. Other distances vs. the 40-cm group, aP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 42-cm group, bP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 44-cm group, cP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 46-cm group, dP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 48-cm group, eP < 0.01; other distances vs. the 50-cm group, fP < 0.01. Significant differences in peak overpressure were observed among the six groups (P < 0.05, F = 12.105). Table 2. Comparison of the shock-wave peak overpressure, impulse induced, and positive pressure duration at different distances

Group (cm) Peak overpressure (MPa) Impulse

(Pa·s)Positive pressure duration (µs) 40 1.34 ± 0.03b,c 44.66 ± 3.74a 435.50 ± 83.24 44 0.75 ± 0.12b 37.41 ± 3.68a 494.75 ± 23.00 48 0.69 ± 0.03c 39.31 ± 2.98 488.00 ± 58.36 Note. 40-cm group vs. 44-cm group, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01; 40-cm group vs. 48-cm group, cP < 0.01. Significant differences in overpressure were observed among the three groups (P < 0.05, F = 96.302). Significant differences in impulses were observed among the three groups (P < 0.05, F = 4.645). -

[1] Chang Y, Zhang DH, Liu LL, et al. Simulation of blast lung injury induced by shock waves of five distances based on finite element modeling of a three-dimensional rat. Sci Rep, 2019; 9, 3440. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40176-7 [2] Cheng TM, Lin Y, Gu DQ, et al. Ultrastructural changes of bone marrow megakaryocytes in several types of injury. Burns Incl Therm Inj, 1984; 10, 282−9. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(84)90007-X [3] Elsayed NM, Atkins J. Explosion and blast-related injuries, amsterdam. Boston: Academic Press; 2008. [4] Song H, Konan LM, Cui J, et al. Ultrastructural brain abnormalities and associated behavioral changes in mice after low-intensity blast exposure. Behav Brain Res, 2018; 347, 148−57. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.03.007 [5] Courtney E, Courtney A, Courtney M. Shock tube design for high intensity blast waves for laboratory testing of armor and combat materiel. Def Technol, 2014; 10, 245−50. doi: 10.1016/j.dt.2014.04.003 [6] Chandra N, Sundaramurthy A, Gupta RK. Validation of laboratory animal and surrogate human models in primary blast injury studies. Mil Med, 2017; 182, 105−13. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00144 [7] Feng K, Zhang L, Jin X, et al. Biomechanical responses of the brain in swine subject to free-field blasts. Front Neurol, 2016; 7, 179. [8] Kabu S, Jaffer H, Petro M, et al. Blast-associated shock waves result in increased brain vascular leakage and elevated ros levels in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. PLoS One, 2015; 10, e0127971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127971 [9] Chai JK, Liu W, Deng HP, et al. A novel model of burn-blast combined injury and its phasic changes of blood coagulation in rats. Shock, 2013; 40, 297−302. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182837831 [10] Hu S, Sheng Z, Xue L, et al. A serilized studies of animal models of posttraumatic multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Med J Chin PLA, 1996; 21, 5−9. (In Chinese) [11] Awwad HO, Gonzalez LP, Tompkins P, et al. Blast overpressure waves induce transient anxiety and regional changes in cerebral glucose metabolism and delayed hyperarousal in rats. Front Neurol, 2015; 6, 132. [12] Chang Y, Zhang DH, Hu Q, et al. Usage of density analysis based on micro-CT for studying lung injury associated with burn-blast combined injury. Burns, 2018; 44, 905−16. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2017.12.010 [13] Zhao Y, Zhou YG. The past and present of blast injury research in China. Chin J Traumatol, 2015; 18, 194−200. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2015.11.001 [14] Prat NJ, Montgomery R, Cap AP, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of coagulation in swine subjected to isolated primary blast injury. Shock, 2015; 43, 598−603. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000346 [15] Watts S, Kirkman E, Bieler D, et al. Guidelines for using animal models in blast injury research. J R Army Med Corps, 2019; 165, 38−40. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2018-000956 [16] Scott TE, Kirkman E, Haque M, et al. Primary blast lung injury - a review. Br J Anaesth, 2017; 118, 311−6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew385 [17] Liu W, Chai JK. Innuences of ulinastatin on acute lung iIljury and time phase changes of coagulation parameters in rats with burn-blast combined injuries. Chin J Burn, 2018; 34, 32−39. (In Chinese) [18] Song H, Cui J, Simonyi A, et al. Linking blast physics to biological outcomes in mild traumatic brain injury: narrative review and preliminary report of an open-field blast model. Behav Brain Res, 2018; 340, 147−58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.08.037 [19] Smith JE, Garner J. Pathophysiology of primary blast injury. J R Army Med Corps, 2019; 165, 57−62. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2018-001058 [20] Mishra V, Skotak M, Schuetz H, et al. Primary blast causes mild, moderate, severe and lethal TBI with increasing blast overpressures: experimental rat injury model. Sci Rep, 2016; 6, 26992. doi: 10.1038/srep26992 [21] Han KH, Ren X, Li H, et al. Simulation and experimental studies on the multi-point synchronization detonation overpressure of slapper detonators. Chinese Journal of Energetic Materials, 2016; 24, 38−44. (In Chinese) [22] Qu ZM, Zhou XQ, He RS, et al. Analysis of attenuation law and characteristic parameters in excavation roadway during gas explosion. Journal of China Society, 2006; 31, 324−328. (In Chinese) [23] Kirkman E, Reade MC. Management of blast related injuries. In Hutchings S, editor. Trauma and Combat Critical Care in Clinical Practice. Cham: Springer, 2016; 225-43. [24] Li HD, Zhang ZR, Chen LA. Experimental study on the pathophysiological change of primary blast injury. Pract J Med Pharm, 2019; 36, 289−92. (In Chinese) [25] Yang ZH, Wang ZG, Tang CG, et al. Biological effects of weak blast waves and safety limits for internal organ injury in the human body. J Trauma, 1996; 40, S81−4. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199603001-00019 [26] Wang ZG, Zhen S, Yang Z, et al. Research on the blast injury. Chin J Trauma, 1986; 2, 193−6. (In Chinese) [27] Chai JK, Sheng ZY, Lu JY, et al. Characteristics of and strategies for patients with severe burn-blast combined injury. Chin Med J, 2007; 120, 1783−7. doi: 10.1097/00029330-200710020-00010 [28] Chai JK, Zheng QY, Li LG, et al. Analysis on treatment of eight extremely severe burn patients in august 2nd Kunshan factory aluminum dust explosion accident. Chin J Burn, 2018; 34, 332−8. (In Chinese) [29] Yelveton JT. Pathology scoring system for blast injuries. J Trauma, 1996; 40, S111−5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199603001-00025 [30] Liu B, Wang Z, Leng H, et al. Pathologic study of thoracic impact injury involving a relatively static impact pattern. J Trauma, 1996; 40, S85−9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199603001-00020 [31] Du PR, Lu HT, Lin XX, et al. Calpain inhibition ameliorates scald burn-induced acute lung injury in rats. Burns Trauma, 2018; 6, 28. [32] Sine CR, Belenkiy SM, Buel AR, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in burn patients: a comparison of the Berlin and American-European definitions. J Burn Care Res, 2016; 37, e461−9. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000348 [33] Liu YE, Tong CC, Zhang YB, et al. Chitosan oligosaccharide ameliorates acute lung injury induced by blast injury through the DDAH1/ADMA pathway. PLoS One, 2018; 13, e0192135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192135 [34] Wang QJ, Ye CQ, Shao XA, et al. Experimental study of acute lung injury in rabbits by underwater blast. J Trauma Surg, 2017; 19, 865−8. (In Chinese) -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links