-

Acute mountain sickness (AMS) is an illness caused by hypoxia due to rapid ascent to altitudes above 2,500 m. Symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite, all of which usually improve within 1 to 2 days. However, untreated AMS can progress to life-threatening conditions such as high-altitude cerebral and pulmonary edema (HACE and HAPE, respectively)[1]. The 2018 Lake Louise Scoring (LLS) system is currently widely utilized in research and practice and has gained international recognition for its sensitivity and specificity in detecting AMS[2]. The reported prevalence of AMS in adults worldwide ranges from 28% to 50%, which may depend on factors such as the rate and mode of ascent, as well as individual differences, including age, obesity status, and sleep quality. Extensive domestic and international research has identified key factors influencing AMS, including rapid ascent, inadequate pre-acclimatization, a history of AMS, sleep quality, and physical activity. Although most scholars agree that AMS is the outcome of various factors, its exact pathogenesis is still not yet fully understood.

With economic development, the number of tourists traveling to Xizang Autonomous Region (Xizang) has been increasing annually, with an associated increase in the incidence of AMS. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive study and analysis of the factors contributing to the onset of AMS. This study focused on Han Chinese tourists entering Xizang to statistically analyze the risk factors associated with AMS and provide a theoretical foundation for its prevention and treatment.

A questionnaire survey was conducted between June 1 and November 30, 2023 to gather data from the Han Chinese people who arrived in Xizang between 2015 and 2023. The survey utilized a combination of online and offline methods. Fieldwork was conducted in Lhasa, Xizang, at an altitude of over 3,000 m. Questionnaires were distributed via the WeChat APP (Tencent, Shenzhen, China) using QR codes generated on the Questionnaire Star platform. A total of 1,430 participants completed the questionnaire. The inclusion criteria for the study population were as follows: (1) being of Han Chinese ethnicity and having recently traveled to Xizang, (2) being of age 18 years or above, (3) having a clear indication of altitude of residence, and (4) having no history of long-term residence at high altitudes or related diseases prior to travel. To eliminate bias, we excluded (1) permanent residents of Xizang and those with long-term exposure to high altitudes, (2) those with underlying diseases, such as chronic cardiopulmonary disease, that could affect the study results, and (3) those with incomplete data. Finally, 1,064 valid questionnaires were included in the analysis.

The 2018 LLS system incorporates a participant’s subjective rating of symptom severity, including headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and dizziness, on a scale of 0 to 3[3]. The sum of these symptom scores determines the total LLS score. AMS was initially diagnosed during mountaineering activities at an altitude above 2,500 m in participants experiencing headaches and having an LLS score of 3 or higher. A total score of 3–5 indicates a mild reaction, 6–9 a moderate reaction, and 10–12 a severe reaction[2]. The questions regarding AMS symptoms on the questionnaire that we used applied to seven days following the participant’s most recent arrival in Xizang to ensure consistency with the assessment of the study participants’ symptoms in the early stages of AMS. Based on this criterion, the participants were divided into two groups: No AMS (n = 635) and AMS (n = 429).

A total of 27 risk variables were examined, with AMS as the outcome variable. Demographic data included sex, age, altitude of residence, marital status, educational level, ethnicity, and body mass index (BMI). High altitude was defined as above 2,500 m, medium altitude as 1,500–2,500 m, and low altitude as below 1,500 m. Participant heights and weights were measured to calculate their BMI, of which the categories were: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m²), overweight (24.0–27.9 kg/m²), and obesity (> 28.0 kg/m²). Disease and family histories were recorded as binary variables (no = 0, yes = 1). Travel information included the number of trips, mode of transportation, and season of arrival, with the latter categorized as May–September or October–April. Behavioral and psychological factors included physical activity, sedentary behavior, smoking, passive smoking, alcohol consumption, and emotional state within 7 days of entering Xizang. The details of how these variables were measured and categorized are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Table S1. Variable assignments

Variable Valuation Y Group No AMS = 0, AMS = 1 X1 Sex Male = 0, Female = 1 X2 Age 18–30 = 0, 30–50 = 1, ≥ 50 = 2 X3 The altitude of residence Low altitudes = 0,

Medium altitudes = 1X4 Marital status Single = 0, Married = 1, Divorced, widowed or other = 2 X5 Ethnicity Han ethnic group = 0, Others = 1 X6 Educational degree Junior high school or below = 0,

Senior high school or vocational high school = 1,

Bachelor degree = 2, Master’s degree or over = 3X7 BMI < 18.5 = 0, 18.5–23.9 = 1,

24.0–27.9 = 2, ≥ 28.0 = 3X8 Hypertension No = 0, Yes = 1 X9 Hyperlipidemia No = 0, Yes = 1 X10 Family history of hypertension No = 0, Yes = 1 X11 Family history of diabetes No = 0, Yes = 1 X12 Family history of hyperlipidemia No = 0, Yes = 1 X13 Family history of atherosclerosis No = 0, Yes = 1 X14 Family history of stroke No = 0, Yes = 1 X15 Number of trips to Xizang First trip to Xizang = 0,

Multiple trips to Xizang= 1,X16 Mode of transportation By airplane = 0, By train = 1, By car = 2,

By other non-motorized transport= 3X17 The season of entry to Xizang May to September = 0,

October to April = 1X18 Taking prophylactic medication No = 0, Yes = 1 X19 Contacting a cold in the week before entering Xizang No = 0, Yes = 1 X20 Contacting a cold within a week of entering Xizang No = 0, Yes = 1 X21 Experiencing anxiety or depression within a week of entering Xizang No = 0, Yes = 1 X22 Regular physical activity No = 0, Yes = 1 X23 Sedentary behavior < 3 h = 0, 3–8 h = 1, ≥ 8 h = 2 X24 Cigarette smoking No smoking = 0, Current smoking = 1,

Quit smoking and no longer smoke = 2X25 Passive smoking No = 0, Yes = 1 X26 Alcohol consumption No = 0, Yes = 1 X27 Emotional state in the six months prior to entering Xizang Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression = 0,

Positive emotions such as cheerfulness and hopefulness = 1, Other emotions=2Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The frequency data are described as rates or constitutive ratios. The Chi-square test was used to examine the association between the risk factors and AMS among the study groups. Variables that showed a significant association with AMS in the univariate models at a P < 0.10 were included in the logistic regression model. We used the forward likelihood ratio for logistic regression analysis. The predictive power of the model was assessed by plotting the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and calibration curves. Decision curve analysis (DCA) and the clinical impact curve (CIC) were used to assess the clinical applicability of the model. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Statistical data processing and analysis were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM; Armonk, NY, USA) and R statistical software (version 4.2.3).

A total of 1,064 cases were included in this study, of which 496 (46.60%) were male and 568 (53.40%) were female, the mean age was (36.59 ± 10.76) years. Those with normal weight accounted for 48.80% and those who were overweight accounted for 26.80%. The general demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Table S2. Demographic characteristics of all study subjects (N = 1,064)

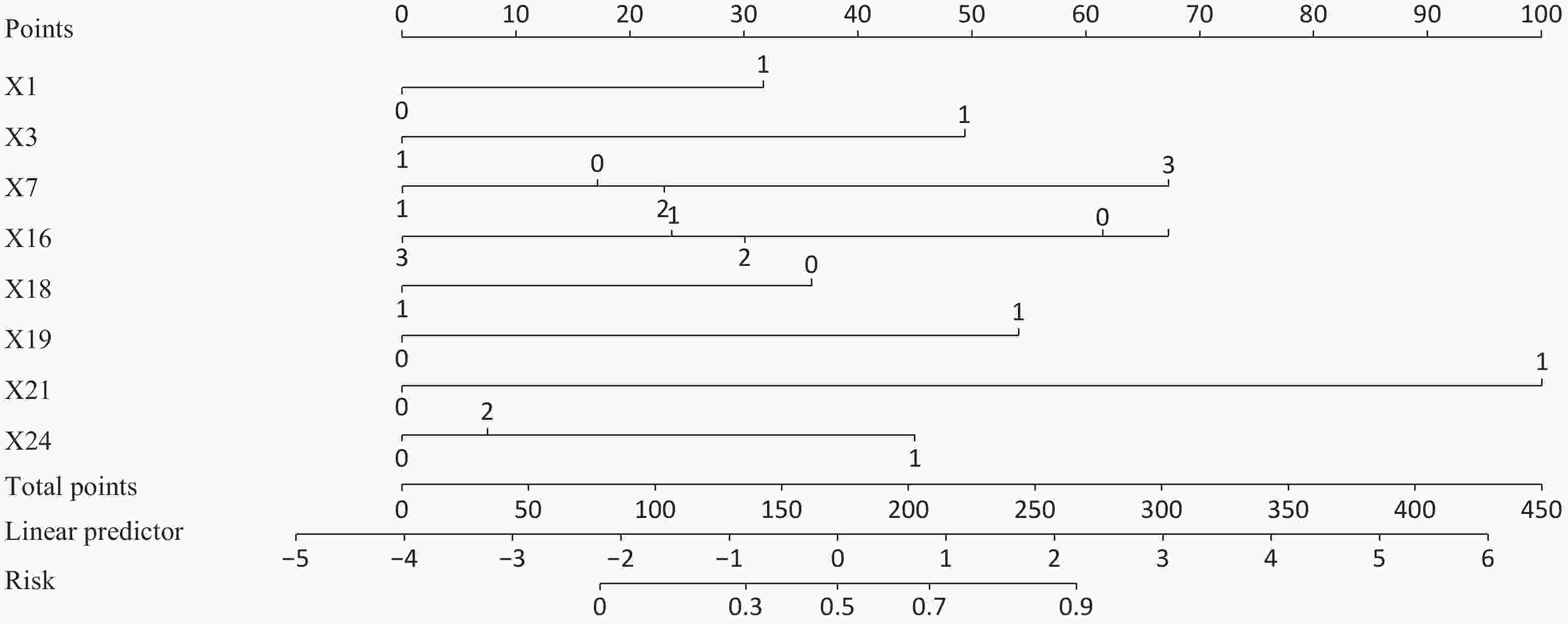

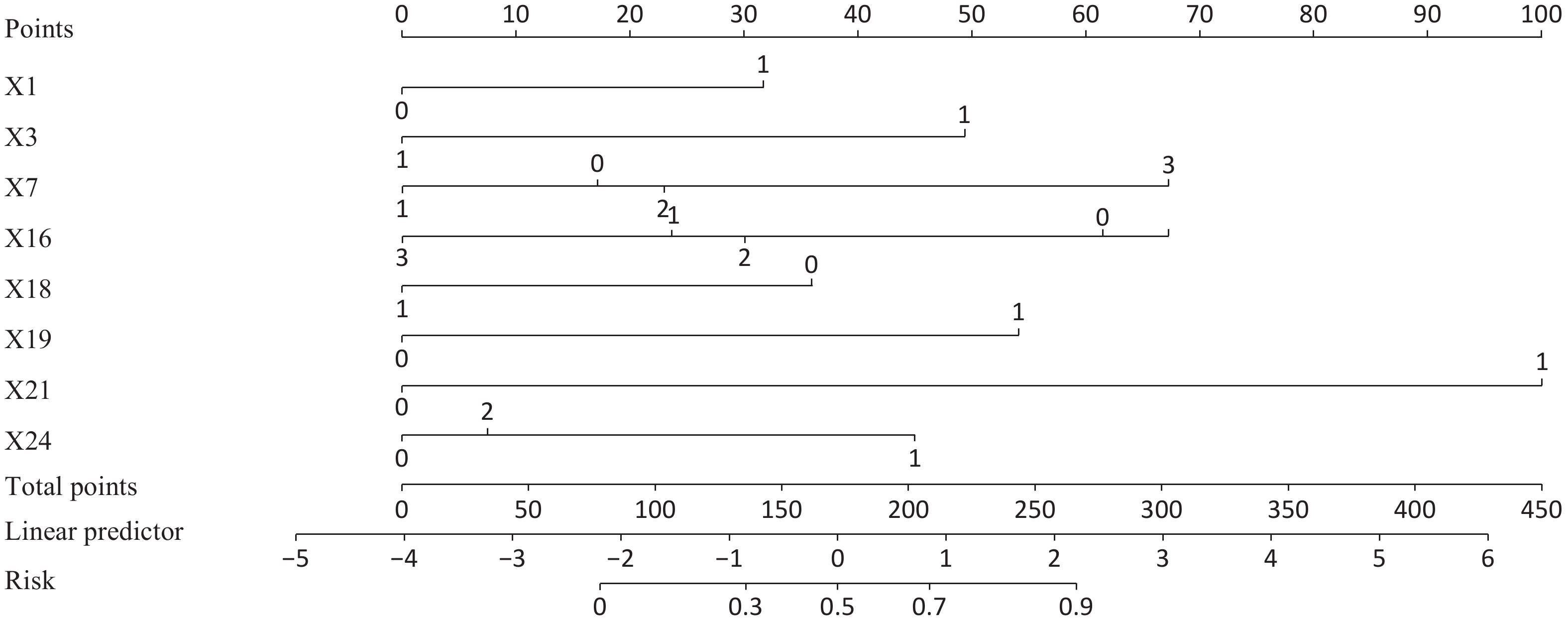

Characteristic Category n (%) Sex Male 496 (46.60) Female 568 (53.40) Age (years) 18–30 329 (30.90) 30–50 574 (53.90) ≥ 50 161 (15.10) The altitude of residence Low altitudes 627 (58.90) Medium altitudes 437 (41.10) Marital status Single 334 (31.40) Married 703 (66.10) Divorced, widowed or other 27 (2.50) Educational degree Junior high school or below 22 (2.10) Senior high school or vocational high school 48 (4.50) Bachelor degree 587 (55.20) Master’s degree or over 407 (38.30) BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 88 (8.30) 18.5–23.9 519 (48.80) 24.0–27.9 285 (26.80) ≥ 28.0 172 (16.20) Chi-square test results showed significant differences between the two groups in 18 variables related to the occurrence of AMS (P < 0.10; Supplementary Table S3). These variables were included in a binary logistic regression analysis. Female participants were more likely to experience AMS than male participants (OR: 2.10; 95% CI: 1.47–2.99). Obesity was also associated with a higher likelihood of AMS compared the absence thereof (OR: 3.23; 95% CI: 1.70–6.11). Similarly, contacting a cold in the week before entering Xizang increased the odds of AMS compared to not having a cold (OR: 3.54; 95% CI: 1.63–7.70). Individuals who experienced a depressed or anxious mood one week after entering Xizang were more likely to have AMS than those who did not (OR: 10.34; 95% CI: 6.48–16.50). Current smoking was also associated with a higher likelihood of developing AMS compared to not smoking (OR: 2.86; 95% CI: 1.90–4.31). In contrast, individuals who lived at medium altitudes were less likely to develop AMS than those who did not (OR: 0.32; 95% CI: 0.22–0.44). There was also a lower risk of AMS for those who traveled by train (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.28–0.61), car (OR: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.33–0.69), and other non-motorized transport (OR: 0.24; 95% CI: 0.10–0.60) compared to those who traveled by airplane to Xizang. Similarly, people who took prophylactic medication were less likely to develop AMS than those who did not (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.32–0.59; Table 1). Based on the results of our logistic regression analysis, a model was established and presented as a nomogram (Figure 1).

Table 1. Results of the logistic regression of the occurrence of acute mountain sickness

Characteristic OR 95% CI P X1 Female 2.10 1.47–2.99 < 0.001 X3 Residing at medium altitudes 0.32 0.22–0.45 < 0.001 X7 Obesity 3.23 1.70–6.11 < 0.001 X16 By train to Xizang 0.41 0.28–0.61 < 0.001 X16 By car to Xizang 0.48 0.33–0.69 < 0.001 X16 By other non-motorized transport to Xizang 0.24 0.10–0.60 0.002 X18 Taking prophylactic medication 0.43 0.32–0.59 < 0.001 X19 Contacting a cold in the week before entering Xizang 3.54 1.63–7.70 0.001 X21 Experiencing anxiety or depression within a week of entering Xizang 10.34 6.48–16.50 < 0.001 X24 Current smoking 2.86 1.90–4.31 < 0.001 Table S3. Results of a univariate analysis of the occurrence of AMS

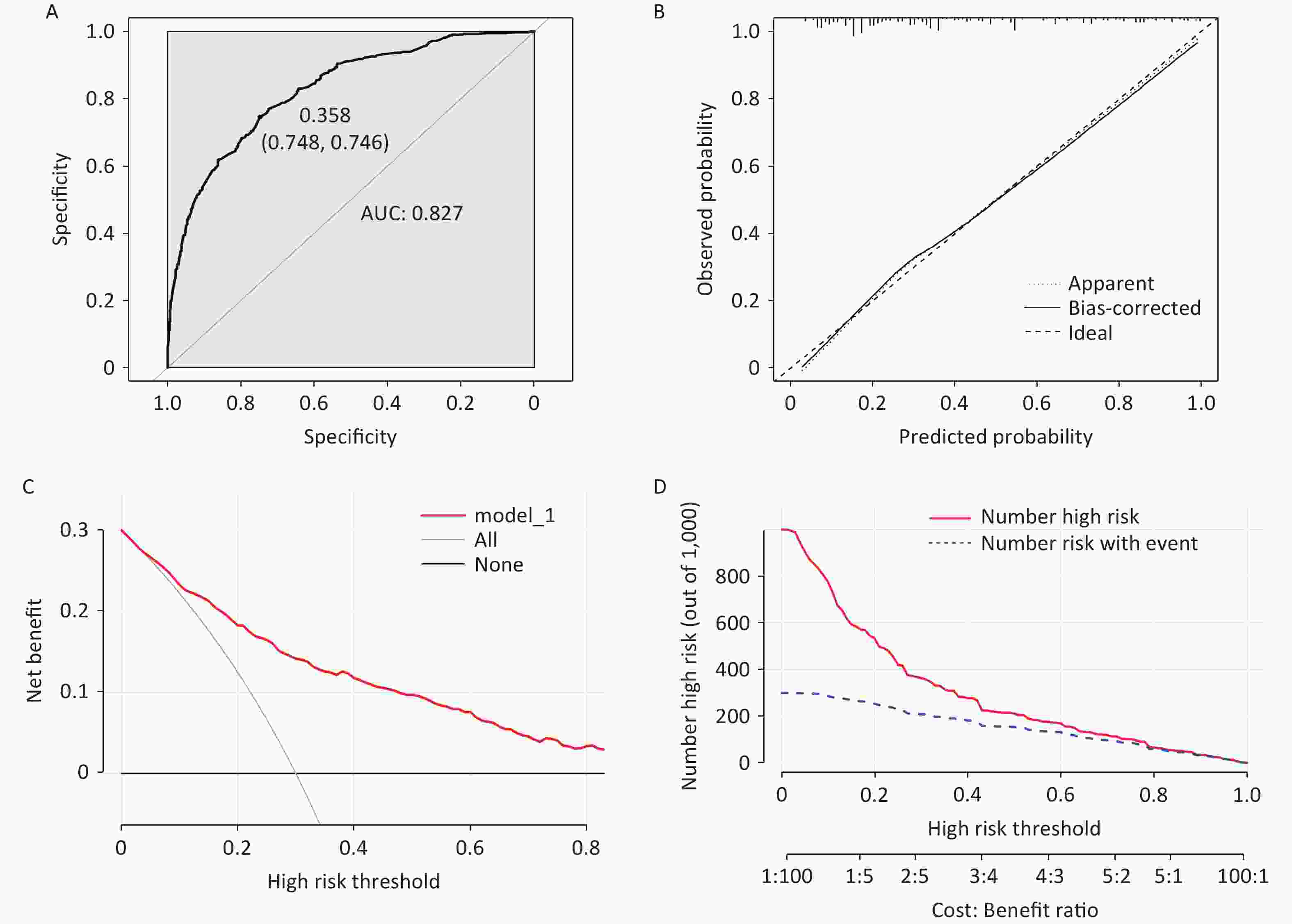

Variable Category No AMS (%) AMS (%) χ2 P value Sex Male 319 (50.20) 177 (41.30) 8.29 0.004 Female 316 (49.80) 252 (58.70) The altitude of residence Low altitudes 319 (50.20) 308 (71.80) 49.17 < 0.001 Medium altitudes 316 (49.80) 121 (28.20) Educational degree Junior high school or below 16 (2.50) 6 (1.40) 18.91 < 0.001 Senior high school or vocational high school 33 (5.20) 15 (3.50) Bachelor degree 376 (59.20) 211 (49.20) Master’s degree or over 210 (33.10) 197 (45.90) BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 50 (7.90) 38 (8.90) 65.99 < 0.001 18.5–23.9 353 (55.60) 166 (38.70) 24.0–27.9 175 (27.60) 110 (25.60) ≥ 28.0 57 (9.00) 115 (26.80) Family history of hypertension No 322 (50.70) 189 (44.10) 4.54 0.033 Yes 313 (49.30) 240 (55.90) Family history of atherosclerosis No 601 (94.60) 392 (91.40) 4.40 0.036 Yes 34 (5.40) 37 (8.60) Number of trips to Xizang First trip to Xizang 390 (36.70) 214 (20.10) 18.49 < 0.001 Multiple trips to Xizang 245 (23.00) 215(20.20) Mode of transportation By airplane 159 (25.00) 238 (55.50) 102.32 < 0.001 By train 199 (31.30) 75 (17.50) By car 248 (39.10) 107 (24.90) By other non-motorized transport 29 (4.60) 9 (2.10) The season of entry to Xizang May to September 508 (80.00) 319 (74.40) 4.71 0.030 October to April 127 (20.00) 110 (25.60) Taking prophylactic medication No 327 (51.50) 295 (68.80) 31.44 < 0.001 Yes 308 (48.50) 134 (31.20) Contacting a cold in the week before entering Xizang No 621 (97.80) 399 (93.00) 14.81 < 0.001 Yes 14 (2.20) 30 (7.00) Contacting a cold within a week of entering Xizang No 615 (96.90) 390 (90.90) 17.26 < 0.001 Yes 20 (3.10) 39 (9.10) Experiencing anxiety or depression within a week of entering Xizang No 603 (95.00) 284 (66.20) 152.71 < 0.001 Yes 32 (5.00) 145 (33.80) Sedentary behavior < 3 h 125 (19.70) 62 (14.50) 5.08 0.079 3–8 h 343 (54.00) 241 (56.20) ≥ 8 h 167 (26.30) 126 (29.40) Cigarette smoking No smoking 492 (77.50) 298 (69.50) 11.59 0.003 Current smoking 102 (16.10) 105 (24.50) Quit smoking and no longer smoke 41 (6.50) 26 (6.10) Passive smoking No 363 (57.20) 210 (49.00) 6.95 0.008 Yes 272 (42.80) 219 (51.00) Alcohol consumption No 358 (56.40) 267 (62.20) 3.63 0.057 Yes 277 (43.60) 162 (37.80) Emotional state in the six months prior to entering Xizang Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression 144 (22.70) 131 (30.50) 8.33 0.004 Positive emotions such as cheerfulness and hopefulness 423 (66.60) 262 (61.10) Other emotions 68 (10.70) 36 (8.40) Discrimination and calibration of the prediction model were assessed using ROC and calibration curves. The area under the curve (AUC) value is 0.827, indicating a well-fitted model with a high predictive accuracy (Figure 2A). The calibration plot in Figure 2B demonstrates a good predictive accuracy between the actual and predicted probabilities. The two lines in the figure are closely aligned, further supporting the high prediction accuracy. Additionally, DCA and CIC analyses were used to determine threshold probabilities, corresponding net benefits, and the number of people at risk according to the model (Figure 2C, D). These results indicate that the model has good clinical utility and predictive effectiveness.

Figure 2. Results of the validation of the model. (A) The area under the curve (AUC) value is 0.827. (B) The calibration curve validates the prediction accuracy. (C, D) Decision curve analysis and clinical impact curve were performed to assess clinical applicability.

Previous studies have indicated that females may be more susceptible to developing AMS than males, possibly because of physiological differences and the influence of sex hormones. Our findings support this view. However, a study by Yang et al.[4] found no difference in the incidence of AMS between sexes, leading to mixed and inconclusive reports on the influence of sex. Our study also found that individuals residing at a low altitude have a higher risk of developing AMS than those residing at a medium altitude. This may be attributed to the difficulty faced by low-altitude residents in adapting to hypoxia environments at high altitudes. Our findings support the hypothesis that obesity is a risk factor for AMS. Hypoxia is believed to have greater metabolic effects in obese individuals, who generally exhibit a higher ratio of basal to maximal oxygen consumption.

Our study found that the mode of transportation to Xizang influences the occurrence of AMS. The ascent to the plateau was faster and more abrupt in the group who traveled by airplane, resulting in a higher incidence of AMS than in the groups who traveled by train and car. Therefore, we hypothesize that a relatively slow, steady ascent and observing “step acclimatization” at an intermediate altitude before moving on to a high altitude is preferable. The results show that prophylactic medication is an effective method for AMS prevention. A reduced risk of AMS in participants taking acetazolamide as prophylactic was reported in a recent study involving travelers to Cusco, Peru[5]. It is hypothesized that these medications not only improve the body’s physiological ability to cope with hypoxic activity, but also provides psychological comfort by reducing anxiety levels.

The association between upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) and AMS was investigated in our study. The results indicate that individuals who caught a cold in the week before entering Xizang were more likely to develop AMS. A prospective cohort study conducted by Chan et al. reported similar findings[6]. Because temperature and oxygen levels tend to decrease as altitude increases, it has been suggested that cold environments could potentially heighten the vulnerability to URIs and place additional strain on the respiratory and circulatory systems, consequently increasing the likelihood of developing AMS.

Individuals who experienced depression or anxiety within a week of entering Xizang had a higher risk of developing AMS than those who did not. It has been established whether exposure to high altitudes can lead to or worsen anxiety symptoms[7]. Studies have indicated that anxiety can affect various organs by disrupting central nervous system function. AMS symptoms can simultaneously contribute to the development of anxiety, demonstrating a complex interplay and synergy between AMS and anxiety.

Previous studies have yielded conflicting results regarding the potential association between smoking and AMS. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies conducted by Vinnikov et al. in occupational populations, indicating that smoking is an essential risk factor for AMS development[8]. However, Gonggalanzi et al. proposed that smoking might decrease nitric oxide (NO) levels[9], potentially protecting smokers from certain symptoms associated with AMS. Therefore, a larger population-based study is required. The predictive model developed in this study can assist clinicians in rapidly assessing the risk of AMS, facilitating the rational allocation of medical resources, supporting clinical decision-making, and enabling timely therapeutic intervention.

Ours was a cross-sectional study with certain inherent limitations that need to be addressed in future studies, such as the small sample size, which may have introduced selection bias and potentially affected the results. Although we have internally validated the nomogram model in our study, it is important to conduct further research using external data to confirm our findings.

doi: 10.3967/bes2025.030

Risk Factors and Predictive Model for Acute Mountain Sickness among Han Chinese Travelers to Xizang Autonomous Region

-

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft, and visualization: Qianhui Gong and Qiong Li. Software, writing, reviewing, and editing: Zhichao Xu. Conceptualization, investigation, writing, review, and revision: Xiaowei Chen. Supervision, project administration: Xiaobing Shen. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Xizang (NO. 2023-001). The purpose of the study was explained in the questionnaire introduction and all participants participated voluntarily and fully informed.

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) Authors’ Contributions: 2) Competing Interests: 3) Ethics: -

S1. Variable assignments

Variable Valuation Y Group No AMS = 0, AMS = 1 X1 Sex Male = 0, Female = 1 X2 Age 18–30 = 0, 30–50 = 1, ≥ 50 = 2 X3 The altitude of residence Low altitudes = 0,

Medium altitudes = 1X4 Marital status Single = 0, Married = 1, Divorced, widowed or other = 2 X5 Ethnicity Han ethnic group = 0, Others = 1 X6 Educational degree Junior high school or below = 0,

Senior high school or vocational high school = 1,

Bachelor degree = 2, Master’s degree or over = 3X7 BMI < 18.5 = 0, 18.5–23.9 = 1,

24.0–27.9 = 2, ≥ 28.0 = 3X8 Hypertension No = 0, Yes = 1 X9 Hyperlipidemia No = 0, Yes = 1 X10 Family history of hypertension No = 0, Yes = 1 X11 Family history of diabetes No = 0, Yes = 1 X12 Family history of hyperlipidemia No = 0, Yes = 1 X13 Family history of atherosclerosis No = 0, Yes = 1 X14 Family history of stroke No = 0, Yes = 1 X15 Number of trips to Xizang First trip to Xizang = 0,

Multiple trips to Xizang= 1,X16 Mode of transportation By airplane = 0, By train = 1, By car = 2,

By other non-motorized transport= 3X17 The season of entry to Xizang May to September = 0,

October to April = 1X18 Taking prophylactic medication No = 0, Yes = 1 X19 Contacting a cold in the week before entering Xizang No = 0, Yes = 1 X20 Contacting a cold within a week of entering Xizang No = 0, Yes = 1 X21 Experiencing anxiety or depression within a week of entering Xizang No = 0, Yes = 1 X22 Regular physical activity No = 0, Yes = 1 X23 Sedentary behavior < 3 h = 0, 3–8 h = 1, ≥ 8 h = 2 X24 Cigarette smoking No smoking = 0, Current smoking = 1,

Quit smoking and no longer smoke = 2X25 Passive smoking No = 0, Yes = 1 X26 Alcohol consumption No = 0, Yes = 1 X27 Emotional state in the six months prior to entering Xizang Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression = 0,

Positive emotions such as cheerfulness and hopefulness = 1, Other emotions=2S2. Demographic characteristics of all study subjects (N = 1,064)

Characteristic Category n (%) Sex Male 496 (46.60) Female 568 (53.40) Age (years) 18–30 329 (30.90) 30–50 574 (53.90) ≥ 50 161 (15.10) The altitude of residence Low altitudes 627 (58.90) Medium altitudes 437 (41.10) Marital status Single 334 (31.40) Married 703 (66.10) Divorced, widowed or other 27 (2.50) Educational degree Junior high school or below 22 (2.10) Senior high school or vocational high school 48 (4.50) Bachelor degree 587 (55.20) Master’s degree or over 407 (38.30) BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 88 (8.30) 18.5–23.9 519 (48.80) 24.0–27.9 285 (26.80) ≥ 28.0 172 (16.20) Table 1. Results of the logistic regression of the occurrence of acute mountain sickness

Characteristic OR 95% CI P X1 Female 2.10 1.47–2.99 < 0.001 X3 Residing at medium altitudes 0.32 0.22–0.45 < 0.001 X7 Obesity 3.23 1.70–6.11 < 0.001 X16 By train to Xizang 0.41 0.28–0.61 < 0.001 X16 By car to Xizang 0.48 0.33–0.69 < 0.001 X16 By other non-motorized transport to Xizang 0.24 0.10–0.60 0.002 X18 Taking prophylactic medication 0.43 0.32–0.59 < 0.001 X19 Contacting a cold in the week before entering Xizang 3.54 1.63–7.70 0.001 X21 Experiencing anxiety or depression within a week of entering Xizang 10.34 6.48–16.50 < 0.001 X24 Current smoking 2.86 1.90–4.31 < 0.001 S3. Results of a univariate analysis of the occurrence of AMS

Variable Category No AMS (%) AMS (%) χ2 P value Sex Male 319 (50.20) 177 (41.30) 8.29 0.004 Female 316 (49.80) 252 (58.70) The altitude of residence Low altitudes 319 (50.20) 308 (71.80) 49.17 < 0.001 Medium altitudes 316 (49.80) 121 (28.20) Educational degree Junior high school or below 16 (2.50) 6 (1.40) 18.91 < 0.001 Senior high school or vocational high school 33 (5.20) 15 (3.50) Bachelor degree 376 (59.20) 211 (49.20) Master’s degree or over 210 (33.10) 197 (45.90) BMI (kg/m2) < 18.5 50 (7.90) 38 (8.90) 65.99 < 0.001 18.5–23.9 353 (55.60) 166 (38.70) 24.0–27.9 175 (27.60) 110 (25.60) ≥ 28.0 57 (9.00) 115 (26.80) Family history of hypertension No 322 (50.70) 189 (44.10) 4.54 0.033 Yes 313 (49.30) 240 (55.90) Family history of atherosclerosis No 601 (94.60) 392 (91.40) 4.40 0.036 Yes 34 (5.40) 37 (8.60) Number of trips to Xizang First trip to Xizang 390 (36.70) 214 (20.10) 18.49 < 0.001 Multiple trips to Xizang 245 (23.00) 215(20.20) Mode of transportation By airplane 159 (25.00) 238 (55.50) 102.32 < 0.001 By train 199 (31.30) 75 (17.50) By car 248 (39.10) 107 (24.90) By other non-motorized transport 29 (4.60) 9 (2.10) The season of entry to Xizang May to September 508 (80.00) 319 (74.40) 4.71 0.030 October to April 127 (20.00) 110 (25.60) Taking prophylactic medication No 327 (51.50) 295 (68.80) 31.44 < 0.001 Yes 308 (48.50) 134 (31.20) Contacting a cold in the week before entering Xizang No 621 (97.80) 399 (93.00) 14.81 < 0.001 Yes 14 (2.20) 30 (7.00) Contacting a cold within a week of entering Xizang No 615 (96.90) 390 (90.90) 17.26 < 0.001 Yes 20 (3.10) 39 (9.10) Experiencing anxiety or depression within a week of entering Xizang No 603 (95.00) 284 (66.20) 152.71 < 0.001 Yes 32 (5.00) 145 (33.80) Sedentary behavior < 3 h 125 (19.70) 62 (14.50) 5.08 0.079 3–8 h 343 (54.00) 241 (56.20) ≥ 8 h 167 (26.30) 126 (29.40) Cigarette smoking No smoking 492 (77.50) 298 (69.50) 11.59 0.003 Current smoking 102 (16.10) 105 (24.50) Quit smoking and no longer smoke 41 (6.50) 26 (6.10) Passive smoking No 363 (57.20) 210 (49.00) 6.95 0.008 Yes 272 (42.80) 219 (51.00) Alcohol consumption No 358 (56.40) 267 (62.20) 3.63 0.057 Yes 277 (43.60) 162 (37.80) Emotional state in the six months prior to entering Xizang Negative emotions such as anxiety and depression 144 (22.70) 131 (30.50) 8.33 0.004 Positive emotions such as cheerfulness and hopefulness 423 (66.60) 262 (61.10) Other emotions 68 (10.70) 36 (8.40) -

[1] Li Q, Xu ZC, Fang FJ, et al. Identification of key pathways, genes and immune cell infiltration in hypoxia of high-altitude acclimatization via meta-analysis and integrated bioinformatics analysis. Front Genet, 2023; 14, 1055372. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1055372 [2] Roach RC, Hackett PH, Oelz O, et al. The 2018 lake Louise acute mountain sickness score. High Alt Med Biol, 2018; 19, 4−6. doi: 10.1089/ham.2017.0164 [3] Xu ZC, Li Q, Shen XB. AZU1 (HBP/CAP37) and PRKCG (PKC-gamma) may be candidate genes affecting the severity of acute mountain sickness. BMC Med Genomics, 2023; 16, 28. doi: 10.1186/s12920-023-01457-3 [4] Yang SL, Ibrahim NA, Jenarun G, et al. Incidence and determinants of acute mountain sickness in Mount Kinabalu, Malaysia. High Alt Med Biol, 2020; 21, 265−72. doi: 10.1089/ham.2020.0026 [5] Caravedo MA, Mozo K, Morales ML, et al. Risk factors for acute mountain sickness in travellers to Cusco, Peru: coca leaves, obesity and sex. J Travel Med, 2022; 29, taab102. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taab102 [6] Chan CW, Lin YC, Chiu YH, et al. Incidence and risk factors associated with acute mountain sickness in children trekking on Jade Mountain, Taiwan. J Travel Med, 2016; 23, tav008. doi: 10.1093/jtm/tav008 [7] Tang XG, Li XC, Xin Q, et al. Anxiety as a risk factor for acute mountain sickness among young Chinese men after exposure at 3800 M: a cross‒sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2023; 19, 2573−83. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S436438 [8] Vinnikov D, Brimkulov N, Krasotski V, et al. Risk factors for occupational acute mountain sickness. Occup Med, 2014; 64, 483−9. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu094 [9] Gonggalanzi, Labasangzhu, Nafstad P, et al. Acute mountain sickness among tourists visiting the high-altitude city of Lhasa at 3658 m above sea level: a cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health, 2016; 74, 23. doi: 10.1186/s13690-016-0134-z -

24536+Supplementary Materials.pdf

24536+Supplementary Materials.pdf

-

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links