-

Tuberculosis (TB) is a formidable global health problem and ranks above HIV as the leading cause of death worldwide. In 2017, a total number of 10.0 million cases of TB were reported, which resulted in 1.3 million TB deaths. Resistance to standard anti-TB drugs poses a major threat to control of TB, and 450, 000 cases of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) were estimated in 2017, which indicates the severity of the problem[1]. Pneumonia is one of the common infectious diseases that cause morbidity and mortality in China, causing approximately 2.5 million new cases and 125, 000 deaths annually[2]. Particularly, a high risk of pneumonia in TB was observed among patients with TB compared to that in the general population[3]. Regarding patients with MDR-TB, the extensive for the focus of lung[4] and lung dysbacteriosis[5] further increase the risk of secondary pneumonia, and the role of secondary pneumonia in the efficacy of anti-TB treatment needs to be delineated.

Therefore, we investigated the association between secondary pneumonia and the outcome of MDR-TB treatment. Patients newly diagnosed as MDR who were retrospectively treated over a period of 12 months in Guangzhou Chest Hospital Tuberclusis Department between January 2014 and January 2017 were included in this study, and those patients who were transferred out or those whose treatment period was for < 12 months were excluded. Assessment was focused on demographic characteristics, chest radiographs, baseline information about comorbidities, serum albumin level, absolute lymphocyte count, sputum analysis results, and certain follow-up information during and after treatment or censorship (death, default, and study termination). The study was approved by the Guangzhou Chest Hospital Ethics Committee. Since this is a retrospective study, no consent for participation was obtained.

For purposes of this study, pneumonia was diagnosed based on clinical signs and chest X-ray features of pneumonia. In addition, complete blood count and sputum culture were performed to establish the causative agent of the pneumonia. All patients in this study were treated using a regimen of amikacin (AMK) or capreomycin (CAP), levofloxacin (LFX) or moxifloxacin (MFX), protionamide (PTO) or p-aminosalicylate (PAS), cycloserine (CLS) or ethambutol (EMB), and pyrazinamide (PZA) for 6 months or LFX or MFX, PTO or PAS, CLS or EMB, and PZA for 18 months. The outcomes of interest were time to sputum-negative conversion, and the rate of sputum culture conversion depending on the treatment outcome (cured, treatment completed, treatment default, treatment failure, and died) classification was based on the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines[6].

Among the 120 patients in this study, 70 developed secondary pneumonia and were categorized into the pneumonia group, and the remaining 50 patients were classified as the control group as they did not develop secondary pneumonia. The incidence density of secondary pneumonia among the patients was 61.8 per 100 person-years. The baseline demographic characteristic results pertaining to drug susceptibility testing, smoking, hypoproteinemia, absolute lymphocyte count, comorbidities, and characteristics changes on chest radiographs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Secondary Pneumonia and Baseline Characteristics of Patients with MDR-TB During 2014-2017

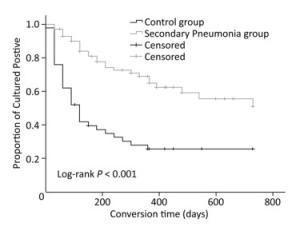

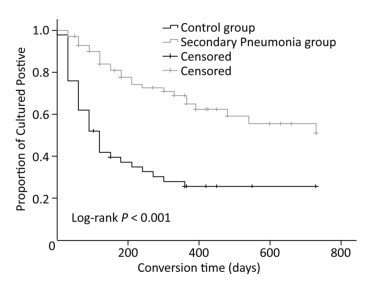

Characteristics Pneumonia Group (n = 70) Control Group (n = 50) P n % n % Age (years) 0.004 < 30 13 18.6 23 46.0 31-59 43 61.4 24 48.0 ≥ 60 14 20.0 3 6.0 Sex 0.845 Male 57 81.4 40 80.0 Female 13 18.6 10 20.0 Drug resistance 0.121 MDR 63 90.0 40 80.0 XDR 7 10.0 10 20.0 Smoke 0.151 No 30 42.9 15 30.0 Yes 40 57.1 35 70.0 With hypoproteinemia (< 35 g/L) 0.002 Yes 20 28.6 3 6.0 No 50 71.4 47 94.0 Low lymphocyte count (< 1 × 109/L) 0.565 Yes 59 84.3 44 88.0 No 11 15.7 6 12.0 With diabetes mellitus 0.831 Yes 18 25.7 12 24.0 No 52 74.3 38 76.0 With bronchiectasis 0.278 Yes 35 50.0 20 40.0 No 35 50.0 30 60.0 With hepatitis* 0.225 Yes 18 25.7 18 36.0 No 52 74.3 32 64.0 With cavities 0.161 No 3 4.3 6 12.0 Yes 67 95.7 44 88.0 Note. *Hepatitis refers to those patients who had normal liver function tests regardless of their serostatus but later had compromised liver function tests. Sputum-negative culture conversion occurred significantly later among the patients with secondary pneumonia (with pneumonia vs. without pneumonia, 512.5 days vs. 263.1 days, P < 0.001), as depicted in Figure 1. In addition, multivariate analysis was performed to adjust for confounders based on unadjusted results, and the association between secondary pneumonia and sputum-negative culture conversion remained uncharged (aHR = 0.354, P = 0.001), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Bivariate and Multivariable HR for Patient Characteristics Associated with Sputum-negative Conversion

Patient Characteristics HR 95% CI P aHR 95% CI P Pneumonia No 1 1 Yes 0.334 (0.201, 0.557) < 0.001 0.354 (0.195, 0.641) 0.001 Age (years) 0.007 0.971 < 30 1 1 31-59 2.553 (1.102, 5.916) 0.029 1.104 (0.447, 2.730) 0.830 ≥ 60 1.171 (0.512, 2.674) 0.709 1.038 (0.454, 2.375) 0.929 Sex Female 1 Male 0.878 (0.476, 1.619) 0.677 Drug resistance MDR 1 XDR 0.597 (0.271, 1.316) 0.201 Smoke No 1 Yes 0.939 (0.261, 1.573) 0.812 With hypoproteinemia No 1 1 Yes 0.475 (0.216, 1.044) 0.064 0.752 (0.324, 1.744) 0.752 Low lymphocyte count No 1 Yes 1.104 (0.544, 2.240) 0.784 With diabetes No 1 1 Yes 0.354 (0.174, 0.721) 0.004 0.332 (0.152, 0.723) 0.006 With bronchiectasis No 1 Yes 1.182 (0.718, 1.946) 0.511 With hepatitis No 1 Yes 0.935 (0.545, 1.606) 0.809 With cavities No 1 1 Yes 0.482 (0.218, 1.065) 0.071 0.736 (0.326, 1.663) 0.462 Note. a, Adjusted for age, with diabetes, with hypoproteinemia, and with cavities. Of the 71 patients with MDR-TB who showed WHO-defined treatment outcome, 11 (15.5%) were cured and 8 (11.3%) completed treatment. The others had poor treatment outcomes and included 26 (36.6%) with defaulted treatment and 21 (29.6%) with treatment failure, whereas 5 (7.0%) patients died. After adjusting for multiple confounders, the results showed that secondary pneumonia increased the risk of poor outcome, although the association was not significant (RR = 1.647, P = 0.146) (Table 2).

Our findings suggested that secondary pneumonia is a significant risk factor that prolonged sputum-negative conversion and treatment failure. Advanced lung disease would lead to lung parenchyma damage, which further compromises the bioavailability of drugs to such tissues[5, 7], resulting in high burden of TB. In this context, the association between cavities and delayed sputum-negative conversion also supported this issue[8].

In particular, previous studies have demonstrated a significant prognostic role of hypoproteinemia in patients with MDR-TB, which suggests the association between malnutrition and poor treatment outcome[8, 9]. Our results showed that malnutrition increased the risk of pneumonia, whereas pneumonia accounted for the malnutrition, resulting in a vicious cycle of infection and malnutrition.

Table 3 shows the results of progression over consecutive sputum cultures. The rate of sputum-negative conversion was significantly lower in the pneumonia group than that in the control group (37.1% vs. 72.0%, P < 0.001). Most importantly, patients with secondary pneumonia easily reconverted to positive events (26.9% in the pneumonia group vs. 11.1% in the control group). Secondary pneumonia reduced the rate of sputum-negative conversion while at the same time led to positive event reconversion. Furthermore, pneumonia increased the minimum time needed for sputum culture-negative conversion. It is worth noting that the time to sputum-negative conversion is associated with treatment outcome in TB[6] and, as indicated by Kurbatova[10], suggests that sputum-negative conversion in 6 months could be a prognostic marker for treatment success. It is therefore not surprising that treatment did not confer similar benefits to patients who converted later during the course of treatment, regardless of the secondary pneumonia or not. All these findings indicate the close association that exists between delayed sputum-negative conversion and poor treatment outcome.

Table 3. Rate of Sputum-negative Conversion and Reconversion between the Two Groups

Items Number of Conversion Events (p-n)* Rate of Conversion Events (p-n)* P Value Number of Reconversion Events (p-n-p)* Rate of Reconversion Events (p-n-p)* P Value Two consecutive sputum cultures Pneumonia group 35 50.0% 0.002 16 45.7% 0.001 Control group 39 78.0% 7 17.9% Total 74 61.7% 23 31.1% Three consecutive sputum cultures Pneumonia group 26 37.1% < 0.001 7 26.9% 0.108 Control group 36 72.0% 4 11.1% Total 62 51.7% 11 17.7% Note.*p indicates positive, n shows negative. 'p-n' indicates positive changed into negative, and 'p-n-p' shows positive changed into negative and then changed into positive again. Studies investigating lung morphological changes and treatment outcome have demonstrated that advanced lung disease reduces drug bioavailability, which eventually leads to poor treatment outcome in TB[5]. Interestingly, our study also revealed an association between chest opacifications and delayed sputum-negative conversion.

No conflict of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the management of Guangzhou Chest Hospital for allowing us to carry out the study.

doi: 10.3967/bes2018.123

The Effects of Secondary Pneumonia on the Curative Efficacy of Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

-

-

Table 1. Secondary Pneumonia and Baseline Characteristics of Patients with MDR-TB During 2014-2017

Characteristics Pneumonia Group (n = 70) Control Group (n = 50) P n % n % Age (years) 0.004 < 30 13 18.6 23 46.0 31-59 43 61.4 24 48.0 ≥ 60 14 20.0 3 6.0 Sex 0.845 Male 57 81.4 40 80.0 Female 13 18.6 10 20.0 Drug resistance 0.121 MDR 63 90.0 40 80.0 XDR 7 10.0 10 20.0 Smoke 0.151 No 30 42.9 15 30.0 Yes 40 57.1 35 70.0 With hypoproteinemia (< 35 g/L) 0.002 Yes 20 28.6 3 6.0 No 50 71.4 47 94.0 Low lymphocyte count (< 1 × 109/L) 0.565 Yes 59 84.3 44 88.0 No 11 15.7 6 12.0 With diabetes mellitus 0.831 Yes 18 25.7 12 24.0 No 52 74.3 38 76.0 With bronchiectasis 0.278 Yes 35 50.0 20 40.0 No 35 50.0 30 60.0 With hepatitis* 0.225 Yes 18 25.7 18 36.0 No 52 74.3 32 64.0 With cavities 0.161 No 3 4.3 6 12.0 Yes 67 95.7 44 88.0 Note. *Hepatitis refers to those patients who had normal liver function tests regardless of their serostatus but later had compromised liver function tests. Table 2. Bivariate and Multivariable HR for Patient Characteristics Associated with Sputum-negative Conversion

Patient Characteristics HR 95% CI P aHR 95% CI P Pneumonia No 1 1 Yes 0.334 (0.201, 0.557) < 0.001 0.354 (0.195, 0.641) 0.001 Age (years) 0.007 0.971 < 30 1 1 31-59 2.553 (1.102, 5.916) 0.029 1.104 (0.447, 2.730) 0.830 ≥ 60 1.171 (0.512, 2.674) 0.709 1.038 (0.454, 2.375) 0.929 Sex Female 1 Male 0.878 (0.476, 1.619) 0.677 Drug resistance MDR 1 XDR 0.597 (0.271, 1.316) 0.201 Smoke No 1 Yes 0.939 (0.261, 1.573) 0.812 With hypoproteinemia No 1 1 Yes 0.475 (0.216, 1.044) 0.064 0.752 (0.324, 1.744) 0.752 Low lymphocyte count No 1 Yes 1.104 (0.544, 2.240) 0.784 With diabetes No 1 1 Yes 0.354 (0.174, 0.721) 0.004 0.332 (0.152, 0.723) 0.006 With bronchiectasis No 1 Yes 1.182 (0.718, 1.946) 0.511 With hepatitis No 1 Yes 0.935 (0.545, 1.606) 0.809 With cavities No 1 1 Yes 0.482 (0.218, 1.065) 0.071 0.736 (0.326, 1.663) 0.462 Note. a, Adjusted for age, with diabetes, with hypoproteinemia, and with cavities. Table 3. Rate of Sputum-negative Conversion and Reconversion between the Two Groups

Items Number of Conversion Events (p-n)* Rate of Conversion Events (p-n)* P Value Number of Reconversion Events (p-n-p)* Rate of Reconversion Events (p-n-p)* P Value Two consecutive sputum cultures Pneumonia group 35 50.0% 0.002 16 45.7% 0.001 Control group 39 78.0% 7 17.9% Total 74 61.7% 23 31.1% Three consecutive sputum cultures Pneumonia group 26 37.1% < 0.001 7 26.9% 0.108 Control group 36 72.0% 4 11.1% Total 62 51.7% 11 17.7% Note.*p indicates positive, n shows negative. 'p-n' indicates positive changed into negative, and 'p-n-p' shows positive changed into negative and then changed into positive again. -

[1] World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2018.2018 ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [2] Guan X, Benjamin JS, Aaron TF, et al. Pneumonia incidence and mortality in mainland China:Systemic review of Chinese and English literature, 1985-2008. J of Pub Health and Prev Med, 2011; 22, 14-19. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/OAPaper/oai_pubmedcentral.nih.gov_2909231 [3] Chang TM, Mou CH, Shen TC, et al. Retrospective cohort evaluation on risk of pneumonia in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016; 95, e4000. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004000 [4] Lim HJ, Park JS, Cho YJ, et al. CD4(+)FoxP3(+) T regulatory cells in drug-susceptible and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb), 2013; 93, 523-8. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2013.06.001 [5] Heo EY, Chun EJ, Lee CH, et al. Radiographic improvement and its predictors in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis, 2009; 13, e371-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.01.007 [6] Falzon D, Jaramillo E, Schünemann HJ, et al. WHO guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis:2011 update. Eur Respir J, 2011; 38, 516-28. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00073611 [7] Tierney DB, Franke MF, Becerra MC, et al. Time to culture conversion and regimen composition in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. PLoS One, 2014; 9, e108035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108035 [8] Tang S, Tan S, Yao L, et al. Risk factors for poor treatment outcomes in patients with MDR-TB and XDR-TB in China:retrospective multi-center investigation. PLoS One, 2013; 8, e82943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082943 [9] Kim HR, Hwang SS, Kim HJ, et al. Impact of extensive drug resistance on treatment outcomes in non-HIV-infected patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis, 2007; 45, 1290-5. doi: 10.1086/522537 [10] Kurbatova EV, Cegielski JP, Lienhardt C, et al. Sputum culture conversion as a prognostic marker for end-of-treatment outcome in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis:a secondary analysis of data from two observational cohort studies. Lancet Respir Med, 2015; 3, 201-9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00036-3 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links