-

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), defined as tuberculosis resistant to rifampicin and isoniazid, is an important public health concern worldwide. According to an estimate by the World Health Organization (WHO), there were 10.6 million incident cases, of whom 0.41 million were infected with MDR-TB[1]. Owing to initial resistance to the two most potent anti-TB drugs, MDR-TB treatment depends on the administration of many second-line drugs over a long period of time[2,3]. Insufficient efficacy and high toxicity result in poor clinical outcomes, thereby accelerating the transmission of this refractory disease. Thus, more efforts are required to develop new anti-TB drugs to counter the spread of drug-resistant tubercle bacilli[4,5].

After more than 40 years of silencing, a limited number of new drugs have been developed for the treatment of tuberculosis, including delamanid (DLM), bedaquiline (BDQ), and pretomanid. Delamanid, a nitro-dihydro-imidazooxazole derivative, shows a potent bactericide activity via inhibiting mycolic acid synthesis[6,7]. Since 2014, it has been used to treat MDR-TB in combination with an optimized background therapy[8]. Previous clinical trials have demonstrated its promising efficacy against MDR-TB. Available data from clinical trials indicate that DLM is generally well-tolerated, and the incidence of drug-related adverse events in the DLM group is comparable to that in the placebo group[9,10]. The most noticeable adverse event associated with DLM use was QTc interval prolongation. The rate of adverse events varies across patient populations owing to pharmacodynamic differences[11,12]. To date, the knowledge of adverse events is notoriously limited in clinical trials, most of which have been conducted in Africa and South America.

The drug-resistant tuberculosis epidemic constitutes a serious threat to TB control programs in China. Specially, the high prevalence of resistance to fluoroquinolones emphasizes the urgent need for promising alternatives to formulate effective regimens against MDR-TB[13,14]. Thus, the combined use of BDQ-DLM would bring new hope to combat this deadly form of tuberculosis. Although promising efficacy can be expected, it also raises concerns regarding safety, especially the additive effect of QTc interval prolongation[15,16]. We retrospectively reviewed patients receiving DLM/BDQ-containing regimens at a TB-specialized hospital. We aimed to present clinical efficacy and safety data for Chinese patients.

-

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), pre-extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (pre-XDR-TB), and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) treated with BDQ alone or BDQ plus DLM between January 1, 2018 and September 30, 2023, in Beijing, China. We studied the safety of the BDQ and BDQ-DLM over the first 24 weeks. Patients included in this study were required to meet four eligibility criteria: (i) 18–65 years of age; (ii) patients with TB with sputum culture results; (iii) MDR-TB, pre-XDR-TB, or XDR-TB diagnosis as confirmed by drug susceptibility testing; and (iv) patients treated with BDQ or BDQ combined with DLM. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age < 18 or > 65 years, (ii) sputum culture-negative TB patients, and (iii) patients who had only received DLM simultaneously.

-

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University. Because this was an observational retrospective study, and all patient data were analyzed anonymously, the need for informed consent was waived by the Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University.

-

According to the WHO definition and reporting framework for TB, Sputum culture conversion was defined when two consecutive sputum cultures, taken at least 30 days apart, were found to be negative in a patient with a positive sputum culture test result at baseline. Time to sputum culture conversion was defined as the period from the date of initiation of BDQ or BDQ combined with DLM to the date of the first negative sputum culture specimen collection in inpatients with sputum culture conversion. Time was calculated in weeks. The rate of sputum culture conversion was defined as the percentage of patients with sputum culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis who tested negative after 24 weeks of treatment and accounted for all registered sputum culture-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients during the same period. The QT-interval, corrected with Frederica’s formula (QTcF), was calculated by study physicians and graded as follows (Expand New Drugs for TB, 2015): normal < 450 ms, grade 1,450–480 ms, grade 2,481–500 ms, grade 3 ≥ 501 ms without cardiac symptoms, and grade 4 ≥ 501 ms or > 60 msec increase from baseline with cardiac symptoms. Participants with grades 3 and 4 QTcF prolongation were identified and reviewed by a cardiologist. MDR-TB, pre-XDR-TB, and XDR-TB are diseases caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin treatment. Pre-XDR-TB was defined as TB that was resistant to rifampicin and fluoroquinolones. XDR-TB was defined as TB resistant to rifampicin, any fluoroquinolone, and at least one bedaquiline or linezolid. Unfavorable outcomes were defined as consecutive positive sputum cultures or discontinuation owing to a prolonged QTc interval. Favorable outcomes were defined as negative sputum culture conversions.

-

The clinical data of the patients who used the new drugs were provided by the Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University. All information was anonymized before being made available to the authors. Baseline characteristics, including demographic information, comorbidities, history of TB treatment, and results of microbiological tests, were provided. Additionally, information regarding the drugs used, treatment duration, and time to sputum culture conversion were provided to the authors. Sputum culture was performed every four weeks, and laboratory tests and electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring were performed every two weeks. We collected the results of the sputum culture and laboratory and ECG monitoring at 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks.

The patients were classified into two groups depending on the drug used. Continuous variables are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and categorical variables are expressed as numbers with percentages. Pearson’s chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables. Student’s t-test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare continuous variables between the two groups. The Kaplan–Meier curve was used to plot the time to sputum culture conversion, and the differences between the groups were analyzed using the log-rank test. During treatment, an ECG showing a QTc value > 450 ms was defined as an adverse event and a QTc value > 500 ms was defined as the withdrawal criterion. Unfavorable outcomes included patients without consecutive sputum culture conversions or patients who discontinued treatment owing to QTc interval prolongation. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 24.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata 12.0 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

-

During the study period, 252 patients with pulmonary MDR-TB, pre-XDR-TB, and XDR-TB were treated with BDQ alone or BDQ combined with DLM. The BDQ combined with DLM and BDQ group were 1:2 matched. Finally, 96 patients were included in this analysis based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: 64 in the BDQ group and 32 in the BDQ + DLM group.

The patients’ median age was 39.0 years (IQR = 32.8–50.3), median body mass index (BMI) was 19.9 (IQR = 19.1–21.4), and 60 (62.5%) patients were male. The median baseline QTc was 402.0 ms (IQR = 387.5–418.0) (P = 0.750). Baseline QTc did not differ between the BDQ and BDQ + DLM groups. Twenty-two (22/96, 22.9%) patients had MDR-TB, 70 (70/96, 72.9%) had pre-XDR-TB, and four (4/96, 4.2%) had XDR-TB. The types of drug resistance, comorbidities, and baseline characteristics of the two groups were not different between the two groups (Table 1). The background regimens consisted of effective anti-TB drugs formulated according to drug susceptibility testing results, including linezolid, clofazimine, cycloserine, amikacin, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, p-aminosalicylic acid, capreomycin, and protionamide. No significant differences were found in the background treatment regimens between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with MDR-TB receiving BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM-containing regimens in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Characteristics Total BDQ BDQ+DLM P-value* Number of patients 96 64 32 Male, N (%) 60 (62.5) 43 (67.2) 17 (53.1) 0.263 Age, median (IQR) 39.0 (32.8–50.3) 39.5 (32.0–49.5) 39.0 (33.0–50.3) 0.809 BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) 19.9 (19.1–21.4) 20.1 (19.1–21.4) 19.6 (18.8–21.3) 0.252 Baseline QTc (ms) (IQR) 402.0 (387.5–418.0) 402.0 (390.0–418.0) 411.5 (384.0–419.0) 0.750 History of TB treatment, N (%) No previous TB treatment 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Previous TB treatment 94 (97.9) 63 (98.4) 31 (96.9) 0.626 Drug resistance, N (%) MDR 22 (22.9) 15 (23.4) 7 (21.9) 0.869 Pre-XDR 70 (72.9) 47 (73.4) 23 (71.9) 0.876 XDR 4 (4.2) 2 (3.1) 2 (6.3) 0.599 Resistance to, N (%) Fluroquinolone 74 (77.1) 49 (76.6) 25 (78.1) 0.865 Ethambutol 48 (50.0) 33 (51.6) 15 (46.9) 0.829 Streptomycin 71 (74.0) 50 (78.1) 21 (65.6) 0.221 Kanamycin 40 (41.7) 29 (45.3) 11 (34.4) 0.382 Amikacin 36 (37.5) 25 (39.1) 11 (34.4) 0.823 Protionamide 26 (27.1) 20 (31.3) 6 (18.6) 0.230 p-aminosalicylic acid 36 (37.5) 25 (39.1) 11 (34.4) 0.823 Linezolid 4 (4.2) 2 (3.1) 2 (6.3) 0.599 Underlying disease, N (%) Thyroid diseases 4 (4.2) 3 (4.7) 1 (3.1) 0.728 Diabetes 20 (20.8) 14 (21.9) 6 (18.8) 0.796 Hypertension 6 (6.3) 5 (7.8) 1 (3.1) 0.660 Hepatitis 2 (2.1) 2 (3.1) 0 (0) 0.551 Mental disease 1 (1.0) 0 (0) 1 (3.1) 0.333 Otolaryngological disease 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Others 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Note. Data are expressed as median (IQR) or number (%); *Mann-Whitney Test. BDQ, bedaquiline, DLM, delamanid, IQR, interquartile range; BMI: body mass index; MDR, multidrug-resistant; Pre-XDR, pre-extensively drug-resistant; XDR, extensively drug-resistant; N, number. Table 2. Companion drugs used in BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM regimens for the treatment of patients with MDR-TB in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Characteristics Total BDQ BDQ+DLM P-value* Number of patients 96 64 32 Anti-TB drugs received at treatment, N (%) Linezolid 91 (94.8) 61 (95.3) 30 (93.8) 0.754 Clofazimine 68 (70.8) 46 (71.9) 22 (68.8) 0.814 Cycloserine 64 (66.7) 43 (67.2) 21 (65.6) 0.883 Amikacin 29 (30.2) 21 (32.8) 8 (25.0) 0.487 Moxifloxacin 16 (16.7) 14 (21.9) 2 (6.3) 0.080 Levofloxacin 13 (13.5) 9 (14.1) 4 (12.5) 0.839 p-aminosalicylic acid 37 (38.5) 29 (45.3) 8 (25.0) 0.075 Capreomycin 18 (18.8) 15 (23.4) 3 (9.4) 0.164 Protionamide 31 (32.3) 24 (37.5) 7 (21.9) 0.166 Note. Data are expressed as number (%); *Mann-Whitney Test. BDQ, bedaquiline; DLM, delamanid; N, number. -

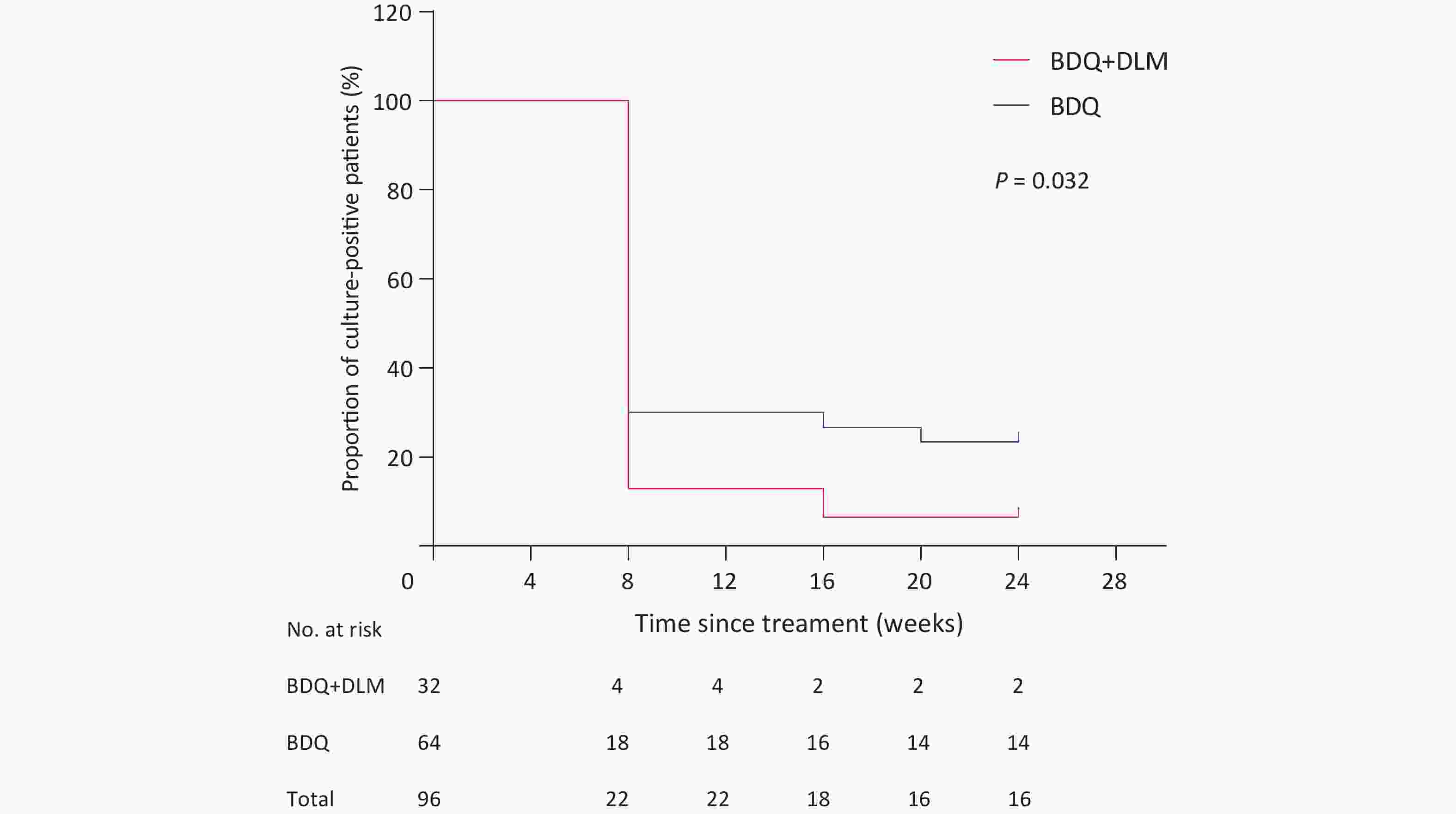

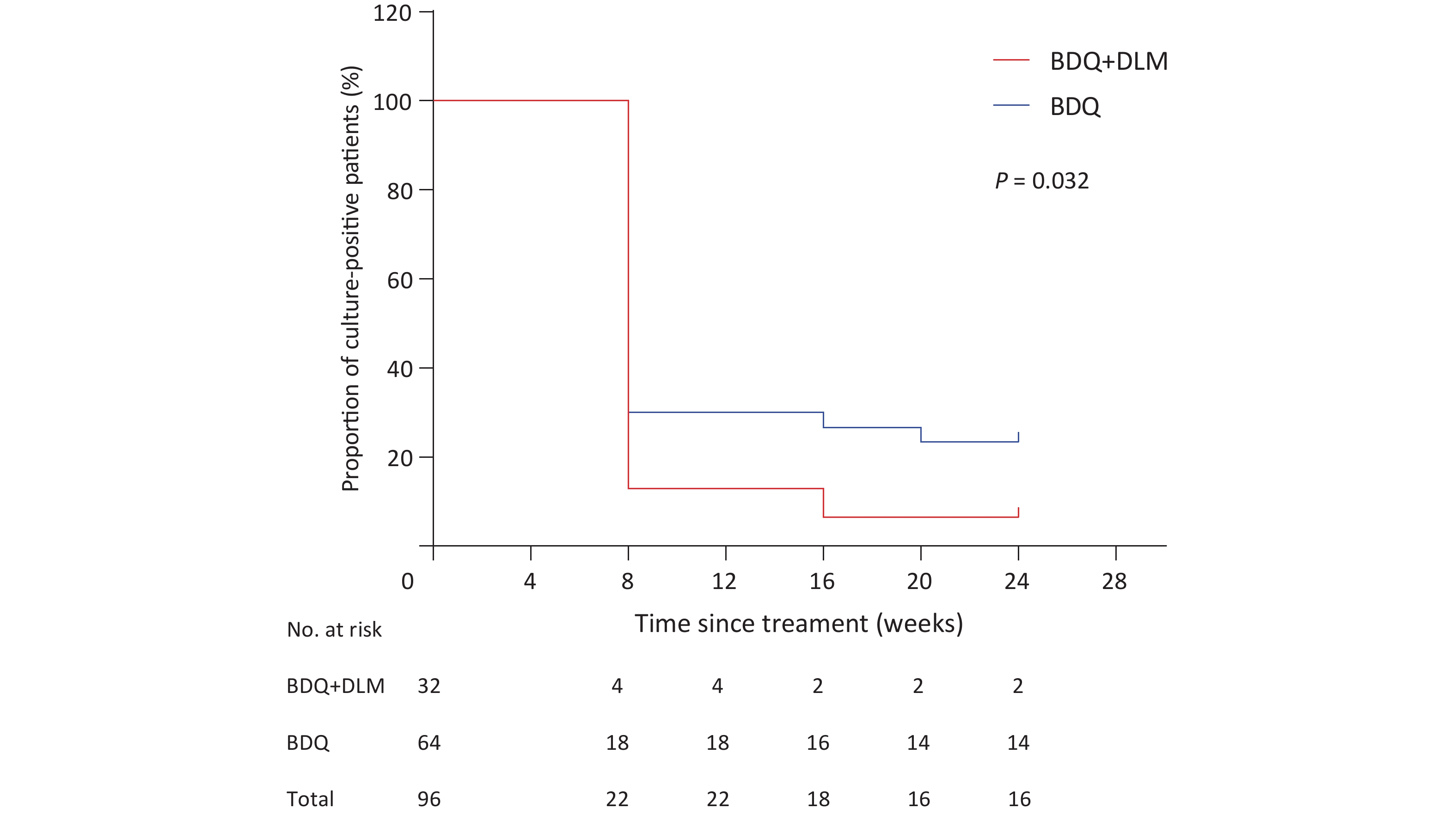

Among the 96 patients with positive sputum cultures at the initiation of BDQ and BDQ combined with DLM, 46 patients (76.7%) in the BDQ group and 29 (93.6%) in the BDQ combined with DLM group had negative bacterial sputum cultures during treatment. Among patients who underwent treatment, fourteen patients were not achieved sputum culture conversion with the new drug in the BDQ group. Two patients in the BDQ-DLM group did not achieve conversion to sputum culture. Four patients in the BDQ group and one patient in the BDQ-DLM group discontinued treatment with BDQ- or BDQ-DLM-containing regimens. The percentage of patients experiencing sputum culture conversion was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.078). During treatment, most patients in both groups achieved sputum culture conversion at eight weeks. The median (IQR) time to culture conversion in both groups was 8 (8, 8) weeks, with no significant difference. With the extension of treatment time, the time to sputum culture conversion in the BDQ-DLM group was significantly shorter than that in the BDQ group (P = 0.032) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Time to sputum culture conversion after starting BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM-containing regimens among patients with MDR-TB in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018-2023 (N = 96). MDR, multidrug-resistant; BDQ, bedaquiline; DLM, delamanid.

In this study, we further analyzed the risk factors associated with the failure to achieve sputum culture conversion. Favorable outcomes (negative sputum culture conversion) were observed in 75 patients (78.1%). Unfavorable outcomes were noted in 21 patients (21.9%), including 5 patients who discontinued treatment (due to QTc interval prolongation) and 16 patients (16.7%) with consecutive positive sputum cultures. Patients with a low body mass index (BMI, < 18.5 kg/m2) (odds ratio [OR], 3.250; 95% CI: 1.055–10.014) had significantly higher odds of experiencing unfavorable outcomes, as determined by multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Table 3. Risk factors associated with unfavorable outcome among patient with MDR-TB receiving BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM regimens in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Characteristics Favorable outcome (N = 75) Unfavorable outcome (N = 21) Crude OR (95% CI) No. % No. % Age (years) < 25 4 5.3 1 4.8 Ref 25–44 41 54.7 12 57.1 1.171 (0.119–11.489) ≥ 45 30 40.0 8 38.1 1.067 (0.104–10.919) BMI (kg/m2) ≥ 18.5 65 86.7 14 66.7 Ref < 18.5 10 13.3 7 33.3 3.250 (1.055–10.014) Sex Female 29 38.7 7 33.3 Ref Male 46 61.3 14 66.7 1.261 (0.455–3.494) Drug resistance MDR 19 25.3 3 14.3 Ref Pre-XDR 53 70.7 17 81.0 2.031 (0.535–7.716) XDR 3 4.0 1 4.7 2.111 (0.162–27.582) Diabetes No 58 77.3 18 85.7 Ref Yes 17 22.7 3 14.3 0.569 (0.149–2.164) Note. Data are expressed as number (%). BDQ, bedaquiline; DLM, delamanid; BMI, body mass index; MDR, multidrug-resistant; Pre-XDR, pre-extensively drug-resistant; XDR, extensively drug-resistant; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; N, number. -

Overall, data analysis revealed that adverse events occurred in 28 (29.2%) of 96 patients. As summarized in Table 4, the most frequent adverse event was QTc prolongation (11/96, 11.5%). QTc interval prolongation and hepatic disorders were the most common adverse events. During treatment, adverse events presumed to be associated with BDQ and BDQ combined with DLM were reported in 20 patients (20.8%). Prolongation of QTc (> 450 ms) occurred in 11 patients (11.5%): seven patients (10.9%) in the BDQ group and four patients (12.5%) in the BDQ combined with DLM group (P = 0.827). Four patients (6.3%) discontinued BDQ and one patient (3.1%) discontinued BDQ combined with DLM because of prolonged QTc at 24 weeks of treatment (P = 0.662). Prolongation of the QTc interval was the major reason for discontinuation of BDQ and BDQ combined with DLM. The frequency of adverse events did not differ between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Adverse events in patients with MDR-TB treated with BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM-containing regimens in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Variable Total BDQ BDQ-DLM P-value* Number of patients 96 64 32 Any adverse events, N (%) 28 (29.2) 18 (28.1) 10 (31.3) 0.814 Adverse events related to treatment, N (%) 27 (28.1) 17 (26.6) 10 (31.3) 0.810 Adverse events presumably due to BDQ/BDQ-DLM, N (%) 20 (20.8) 12 (18.8) 8 (25.0) 0.595 Adverse events with, N (%) QTc interval prolongation 11 (11.5) 7 (10.9) 4 (12.5) 0.827 Hepatic disorder 4 (4.2) 3 (4.7) 1 (3.1) 0.728 Renal disorder 1 (1.0) 1 (1.6) 0 (0) 0.493 Nausea 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Electrolyte disturbance 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Peripheral neuropathy 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Neutropenia 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Optic neuropathy 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Heart failure 2 (2.1) 2 (3.1) 0 (0) 0.551 QTc interval prolongation (ms) 450–499 6 (6.3) 3 (4.7) 3 (9.4) 0.660 ≥ 500 5 (5.2) 4 (6.3) 1 (3.1) 0.662 Note. Data are expressed as number (%); *Mann-Whitney Test. BDQ, bedaquiline, DLM, delamanid; N, number. -

In this study, we retrospectively compared short-term treatment outcomes and safety data in patients with MDR-TB who received BDQ or BDQ-DLM combination therapy. Our data demonstrated that 93.6% of patients with MDR-TB achieved sputum culture conversion at 24 weeks in the BDQ-DLM group compared to 76.7% in the BDQ group. Similar results were observed in a recent prospective controlled trial conducted in South Africa. Eighty-two percent of patients with MDR-TB receiving BDQ-DLM combination therapy achieved sputum culture conversion after six months of treatment[13]. Dooley et al. also found that sputum culture conversion within 24 weeks was noted in 95% of patients treated with a combination of BDQ and DLM[17]. In contrast, a recent study by Vambe et al. found an elevated risk of unfavorable treatment outcomes when patients were treated with a combination of BDQ and DLM compared with BDQ alone[18]. This difference across studies may be attributed to enrolment bias in patients in the combination therapy group, which has a higher extent of drug resistance, entailing more treatment modifications.

Additionally, patients with MDR-TB in the BDQ-DLM group converted to a sputum culture-negative status sooner than those in the BDQ group, suggesting the potent early bactericidal activity of DLM against tubercle bacilli. In a guinea pig model of TB, DLM showed comparable capability to kill rapidly replicating TB bacilli to high concentrations of isoniazid[6,19]. Moreover, DLM is bactericidal against dormant bacilli, a heterogeneous TB bacillus population, and can effectively kill bacilli in the hypoxic region within the granuloma, which may be another explanation for the shorter time to conversion in patients with MDR-TB[20,21]. Accelerated clearance of tubercle bacilli is essential for inhibiting in vivo multiplication, thereby preventing the accumulation of genetic mutations that confer drug resistance.

Another important concern is related to adverse events, especially cardiac adverse events, when a combination of BDQ and DLM is used. The most common clinically relevant adverse event observed in these patients with MDR-TB was QTc interval prolongation, accounting for 3.1% of patients who experienced QTc prolongation ≥ 500 ms. Notably, the combined use of BDQ and DLM did not increase risk of the incidence of QTc interval prolongation relative to BDQ alone. Our data compare favorably with the results obtained from the pooled analysis of several studies, confirming that the combined treatment exhibited good tolerability in most cases. Despite evidence of safety of combined therapy, we need to acknowledge that 12.5% of patients had QTc prolongation ≥ 450 ms in our cohort. Similar results were observed in a prospective study conducted in a Chinese population, in which QTc prolongation occurred in 22% of patients with MDR-TB treated with BDQ-containing regimens, suggesting a high susceptibility to cardiac adverse events associated with the administration of BDQ and other QTc-prolonging drugs in the Chinese population[22,23]. More frequent ECG monitoring is required to improve the management of adverse cardiac events in this population. Studies have shown that a high risk of tuberculosis is associated with a lower body weight or BMI. BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 may be due to protein and/or caloric deficiencies, leading to impaired immune function[24].

In our MDR-TB cohort, the overall mortality of patients on bedaquiline-containing regimens was 0.0%, compared to previously reported mortality rates ranging from 6.8% in France to 20% in South Africa[25,26]. Our lower mortality rate may reflect the low proportion of TB patients co-infected with HIV in this study, since HIV infection is considered a major predictor of TB patient mortality[27,28]. In addition, BDQ pilot studies completed to date were conducted in tertiary care hospitals that lacked the resources and clinicians to monitor and support patients with BDQ during outpatient follow-up[29]. Such support would improve patient access to better medical care to prevent or respond to multiple adverse events, leading to improved survival observed in this study.

The present study has several limitations. First, the major limitation was the retrospective study design, and patient enrolment bias may have existed, which may weaken the significance of our conclusions. Further confirmation of this finding in a prospective randomized study is warranted. Second, we only reviewed sputum culture conversion among patients who completed a 6-month course of BDQ- or BDQ-DLM-containing regimens, which did not mention baseline X-ray data, the pharmacokinetics of patients in different drug groups, and available follow-up DST, limiting conclusions on clinical outcomes after completion of the treatment course. This study did not attempt to discontinue clofazimine before permanently discontinuing BDQ-DLM to lessen the additive QTc prolongation effect. Third, only HIV-naive adult patients were included in the analysis. Substantial heterogeneity between study populations can be expected; thus, the limited selection of the background population may hamper the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the combined use of BDQ and DLM is efficacious and tolerable in Chinese patients infected with MDR-TB. Patients in the BDQ-DLM group converted to sputum culture-negative status sooner than those in the BDQ group. Further confirmation of this finding in a prospective randomized study is warranted.

doi: 10.3967/bes2024.088

Efficacy and Safety of Combined Bedaquiline and Delamanid Use among Patients with Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Beijing, China

-

Abstract:

Objectives The combined use of bedaquiline and delamanid (BDQ-DLM) is limited by an increased risk of prolonging the QTc interval. We retrospectively evaluated patients who received DLM/BDQ-containing regimens at a TB-specialized hospital. We aimed to present clinical efficacy and safety data for Chinese patients. Methods This case–control study included patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) treated with BDQ alone or BDQ plus DLM. Results A total of 96 patients were included in this analysis: 64 in the BDQ group and 32 in the BDQ + DLM group. Among the 96 patients with positive sputum culture at the initiation of BDQ alone or BDQ combined with DLM, 46 patients (71.9%) in the BDQ group and 29 (90.6%) in the BDQ-DLM group achieved sputum culture conversion during treatment. The rate of sputum culture conversion did not differ between the two groups. The time to sputum culture conversion was significantly shorter in the BDQ-DLM group than in the BDQ group. The most frequent adverse event was QTc interval prolongation; however, the frequency of adverse events did not differ between the groups. Conclusion In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the combined use of BDQ and DLM is efficacious and tolerable in Chinese patients infected with MDR-TB. Patients in the BDQ-DLM group achieved sputum culture conversion sooner than those in the BDQ group. -

Key words:

- Multidrug resistant /

- Tuberculosis /

- Bedaquiline /

- Delamanid /

- Efficacy /

- Safety

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University.

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: 2) CONFLICT OF INTEREST: 3) ETHICS APPROVAL: -

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with MDR-TB receiving BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM-containing regimens in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Characteristics Total BDQ BDQ+DLM P-value* Number of patients 96 64 32 Male, N (%) 60 (62.5) 43 (67.2) 17 (53.1) 0.263 Age, median (IQR) 39.0 (32.8–50.3) 39.5 (32.0–49.5) 39.0 (33.0–50.3) 0.809 BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) 19.9 (19.1–21.4) 20.1 (19.1–21.4) 19.6 (18.8–21.3) 0.252 Baseline QTc (ms) (IQR) 402.0 (387.5–418.0) 402.0 (390.0–418.0) 411.5 (384.0–419.0) 0.750 History of TB treatment, N (%) No previous TB treatment 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Previous TB treatment 94 (97.9) 63 (98.4) 31 (96.9) 0.626 Drug resistance, N (%) MDR 22 (22.9) 15 (23.4) 7 (21.9) 0.869 Pre-XDR 70 (72.9) 47 (73.4) 23 (71.9) 0.876 XDR 4 (4.2) 2 (3.1) 2 (6.3) 0.599 Resistance to, N (%) Fluroquinolone 74 (77.1) 49 (76.6) 25 (78.1) 0.865 Ethambutol 48 (50.0) 33 (51.6) 15 (46.9) 0.829 Streptomycin 71 (74.0) 50 (78.1) 21 (65.6) 0.221 Kanamycin 40 (41.7) 29 (45.3) 11 (34.4) 0.382 Amikacin 36 (37.5) 25 (39.1) 11 (34.4) 0.823 Protionamide 26 (27.1) 20 (31.3) 6 (18.6) 0.230 p-aminosalicylic acid 36 (37.5) 25 (39.1) 11 (34.4) 0.823 Linezolid 4 (4.2) 2 (3.1) 2 (6.3) 0.599 Underlying disease, N (%) Thyroid diseases 4 (4.2) 3 (4.7) 1 (3.1) 0.728 Diabetes 20 (20.8) 14 (21.9) 6 (18.8) 0.796 Hypertension 6 (6.3) 5 (7.8) 1 (3.1) 0.660 Hepatitis 2 (2.1) 2 (3.1) 0 (0) 0.551 Mental disease 1 (1.0) 0 (0) 1 (3.1) 0.333 Otolaryngological disease 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Others 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Note. Data are expressed as median (IQR) or number (%); *Mann-Whitney Test. BDQ, bedaquiline, DLM, delamanid, IQR, interquartile range; BMI: body mass index; MDR, multidrug-resistant; Pre-XDR, pre-extensively drug-resistant; XDR, extensively drug-resistant; N, number. Table 2. Companion drugs used in BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM regimens for the treatment of patients with MDR-TB in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Characteristics Total BDQ BDQ+DLM P-value* Number of patients 96 64 32 Anti-TB drugs received at treatment, N (%) Linezolid 91 (94.8) 61 (95.3) 30 (93.8) 0.754 Clofazimine 68 (70.8) 46 (71.9) 22 (68.8) 0.814 Cycloserine 64 (66.7) 43 (67.2) 21 (65.6) 0.883 Amikacin 29 (30.2) 21 (32.8) 8 (25.0) 0.487 Moxifloxacin 16 (16.7) 14 (21.9) 2 (6.3) 0.080 Levofloxacin 13 (13.5) 9 (14.1) 4 (12.5) 0.839 p-aminosalicylic acid 37 (38.5) 29 (45.3) 8 (25.0) 0.075 Capreomycin 18 (18.8) 15 (23.4) 3 (9.4) 0.164 Protionamide 31 (32.3) 24 (37.5) 7 (21.9) 0.166 Note. Data are expressed as number (%); *Mann-Whitney Test. BDQ, bedaquiline; DLM, delamanid; N, number. Table 3. Risk factors associated with unfavorable outcome among patient with MDR-TB receiving BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM regimens in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Characteristics Favorable outcome (N = 75) Unfavorable outcome (N = 21) Crude OR (95% CI) No. % No. % Age (years) < 25 4 5.3 1 4.8 Ref 25–44 41 54.7 12 57.1 1.171 (0.119–11.489) ≥ 45 30 40.0 8 38.1 1.067 (0.104–10.919) BMI (kg/m2) ≥ 18.5 65 86.7 14 66.7 Ref < 18.5 10 13.3 7 33.3 3.250 (1.055–10.014) Sex Female 29 38.7 7 33.3 Ref Male 46 61.3 14 66.7 1.261 (0.455–3.494) Drug resistance MDR 19 25.3 3 14.3 Ref Pre-XDR 53 70.7 17 81.0 2.031 (0.535–7.716) XDR 3 4.0 1 4.7 2.111 (0.162–27.582) Diabetes No 58 77.3 18 85.7 Ref Yes 17 22.7 3 14.3 0.569 (0.149–2.164) Note. Data are expressed as number (%). BDQ, bedaquiline; DLM, delamanid; BMI, body mass index; MDR, multidrug-resistant; Pre-XDR, pre-extensively drug-resistant; XDR, extensively drug-resistant; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; N, number. Table 4. Adverse events in patients with MDR-TB treated with BDQ- or BDQ combined with DLM-containing regimens in Beijing Chest Hospital, China, 2018–2023 (N = 96)

Variable Total BDQ BDQ-DLM P-value* Number of patients 96 64 32 Any adverse events, N (%) 28 (29.2) 18 (28.1) 10 (31.3) 0.814 Adverse events related to treatment, N (%) 27 (28.1) 17 (26.6) 10 (31.3) 0.810 Adverse events presumably due to BDQ/BDQ-DLM, N (%) 20 (20.8) 12 (18.8) 8 (25.0) 0.595 Adverse events with, N (%) QTc interval prolongation 11 (11.5) 7 (10.9) 4 (12.5) 0.827 Hepatic disorder 4 (4.2) 3 (4.7) 1 (3.1) 0.728 Renal disorder 1 (1.0) 1 (1.6) 0 (0) 0.493 Nausea 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Electrolyte disturbance 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Peripheral neuropathy 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Neutropenia 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Optic neuropathy 2 (2.1) 1 (1.6) 1 (3.1) 0.626 Heart failure 2 (2.1) 2 (3.1) 0 (0) 0.551 QTc interval prolongation (ms) 450–499 6 (6.3) 3 (4.7) 3 (9.4) 0.660 ≥ 500 5 (5.2) 4 (6.3) 1 (3.1) 0.662 Note. Data are expressed as number (%); *Mann-Whitney Test. BDQ, bedaquiline, DLM, delamanid; N, number. -

[1] Bagcchi S. WHO's global tuberculosis report 2022. Lancet Microbe, 2023; 4, e20. [2] Singh B. Bedaquiline in drug-resistant tuberculosis: a mini-review. Curr Mol Pharmacol, 2023; 16, 243−53. [3] Espinosa-Pereiro J, Sánchez-Montalvá A, Aznar ML, et al. MDR tuberculosis treatment. Medicina (Kaunas), 2022; 58, 188. [4] Van Crevel R, Critchley JA. The interaction of diabetes and tuberculosis: translating research to policy and practice. Trop Med Infect Dis, 2021; 6, 8. [5] Tiberi S, Utjesanovic N, Galvin J, et al. Drug resistant TB - latest developments in epidemiology, diagnostics and management. Int J Infect Dis, 2022; 124 Suppl 1, S20-5. [6] Chen XH, Hashizume H, Tomishige T, et al. Delamanid kills dormant mycobacteria in vitro and in a guinea pig model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2017; 61, e02402−16. [7] Li Y, Sun F, Zhang WH. Bedaquiline and delamanid in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: promising but challenging. Drug Dev Res, 2019; 80, 98−105. [8] Ryan NJ, Lo JH. Delamanid: first global approval. Drugs, 2014; 74, 1041−5. [9] Gler MT, Skripconoka V, Sanchez-Garavito E, et al. Delamanid for multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N Engl J Med, 2012; 366, 2151−60. [10] Khoshnood S, Taki E, Sadeghifard N, et al. Mechanism of action, resistance, synergism, and clinical implications of delamanid against multidrug-resistant mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Microbiol, 2021; 12, 717045. [11] Liu YG, Matsumoto M, Ishida H, et al. Delamanid: from discovery to its use for pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Tuberculosis, 2018; 111, 20−30. [12] Guglielmetti L, Chiesi S, Eimer J, et al. Bedaquiline and delamanid for drug-resistant tuberculosis: a clinician's perspective. Future Microbiol, 2020; 15, 779−99. [13] Huerga H, Khan U, Bastard M, et al. Safety and effectiveness outcomes from a 14-country cohort of patients with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis treated concomitantly with Bedaquiline, Delamanid, and other second-line drugs. Clin Infect Dis, 2022; 75, 1307−14. [14] Liebenberg D, Gordhan BG, Kana BD. Drug resistant tuberculosis: implications for transmission, diagnosis, and disease management. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022; 12, 943545. [15] Olayanju O, Esmail A, Limberis J, et al. A regimen containing bedaquiline and delamanid compared to bedaquiline in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J, 2020; 55, 1901181. [16] Hewison C, Khan U, Bastard M, et al. Safety of treatment regimens containing Bedaquiline and Delamanid in the endTB cohort. Clin Infect Dis, 2022; 75, 1006−13. [17] Dooley KE, Rosenkranz SL, Conradie F, et al. QT effects of bedaquiline, delamanid, or both in patients with rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis: a phase 2, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis, 2021; 21, 975−83. [18] Vambe D, Kay AW, Furin J, et al. Bedaquiline and delamanid result in low rates of unfavourable outcomes among TB patients in Eswatini. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2020; 24, 1095−102. [19] Padmapriyadarsini C, Vohra V, Bhatnagar A, et al. Bedaquiline, delamanid, linezolid, and clofazimine for treatment of pre-extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis, 2022; 76, e938−46. [20] Gupta R, Wells CD, Hittel N, et al. Delamanid in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2016; 20, 33−7. [21] Borah P, Deb PK, Venugopala KN, et al. Tuberculosis: an update on pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms of drug resistance, newer anti-TB drugs, treatment regimens and host- directed therapies. Curr Top Med Chem, 2021; 21, 547−70. [22] Tanneau L, Svensson EM, Rossenu S, et al. Exposure-safety analysis of QTc interval and transaminase levels following bedaquiline administration in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol, 2021; 10, 1538−49. [23] Putra ON, Yulistiani Y, Soedarsono S. Scoping review: QT interval prolongation in regimen containing bedaquiline and delamanid in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Mycobacteriol, 2022; 11, 349−55. [24] Lönnroth K, Williams BG, Cegielski P, et al. A consistent log-linear relationship between tuberculosis incidence and body mass index. Int J Epidemiol, 2010; 39, 149−55. [25] Guglielmetti L, Le Dû D, Jachym M, et al. Compassionate use of bedaquiline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: interim analysis of a French cohort. Clin Infect Dis, 2015; 60, 188−94. [26] Zhao Y, Fox T, Manning K, et al. Improved treatment outcomes with Bedaquiline when substituted for second-line injectable agents in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis, 2019; 68, 1522−9. [27] Kawai V, Soto G, Gilman RH, et al. Tuberculosis mortality, drug resistance, and infectiousness in patients with and without HIV infection in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2006; 75, 1027−33. [28] Yang QL, Han JJ, Shen JJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in adults with HIV. Medicine, 2022; 101, e30405. [29] Khoshnood S, Goudarzi M, Taki E, et al. Bedaquiline: current status and future perspectives. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2021; 25, 48−59. -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links