-

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE), a human viral infectious disease of the central nervous system caused by the tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), is a serious public health problem in several European and North Asian countries[1, 2].

TBEV is in the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae. Its genome is an 11-kb single-stranded RNA molecule encoding three structural (C, M, and E) and seven non-structural (NS1, NS2a, NS2b, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, and NS5) proteins[3]. TBEV is transmitted by different tick species depending on the geographical region. Two species have been identified as the chief vectors that transmit the virus: Ixodes persulcatus and Ixodes ricinus[4, 5]. TBEV is divided into the European subtype (carried by I. ricinus), and the Siberian and Far-Eastern subtypes (both carried by I. persulcatus)[6-8]. In China, TBE is epidemic in the spring and summer in the forest areas of northern China[9]. The main subtype identified in China is the Far-Eastern subtype[6, 7]. In recent years, the incidence of TBE has increased in Eurasia, including China, and TBEV has been spreading to new areas, possibly because of climate change[10, 11]. This new trend in TBE infection poses a serious threat to public health in Europe and Asia.

Currently, the diagnosis of TBE is based on the demonstration of specific IgM antibodies in a patient's serum that appear up to about 2 weeks post-infection[12]. Viral RNA detection techniques based on traditional reverse transcription-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR), and next-generation sequencing are valuable for a molecular diagnosis using blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the early stage of infection[13-18]. However, these methods are costly, time-consuming, and require highly specialized equipment, making them unsuitable for wide application in the field or in resource-limited laboratories.

Recombinase-aided amplification (RAA) is a new isothermal amplification technology that uses specific enzymes and protein for DNA amplification at 39 ℃ in less than 30 min. The enzymatic mixture used in RAA includes single-strand DNA-binding protein (SSB), UvsX recombinase (anneals the primers to the template DNA), and DNA polymerase (for amplification and extension). A RAA assay can also use reverse transcriptase and a fluorescent probe system for the real-time detection of RNA amplicons[19, 20]. RAA has already been applied to detect bacterial and viral pathogens[20-22].

The objective of this study was to develop a reverse-transcription RAA (RT-RAA) assay for the rapid detection of Far East TBEV RNA and to evaluate its performance in tick specimens.

-

The Senzhang strain (GenBank accession no. AM600965, Far-Eastern subtype) preserved in our lab was used as the reference standard[23]. Vero E6 (ATCC CRL-1586) cells cultivated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin, and 1% streptomycin were infected with the TBE virus (multiplicity of infection = 1). After 3-5 days, the cell culture supernatant was harvested. Viral titers [plaque-forming units (pfus)] were determined using a plaque assay, as described by Cao et al.[24].

-

In total, 203 full-length sequences of TBE were downloaded from GenBank and aligned using ClustalX ver. 2.0. The most conservative regions were identified manually for designing primers and probes. Primer Express 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to evaluate the physical properties of the primers and probes. Ultimately, the primers and probes were designed based on the NS5 region of the Far-Eastern subtype sequence (Table 1). All primers and probes were synthesized and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

Table 1. Sequences of Primers and Probes for RT-RAA Assays for TBEV

Primers/Probes Sequence (5′-3′) Genomic Region Genomic Position Product Size (bp) TBE-F CCTTTGGACAGCAGCGAGTGTTCAARGAGAA NS5 8708-8739 TBE-R CTATGAAYTCCTCTCTGCTGCACATTCGTGG NS5 8836-8866 159 TBE-Probe* AGGCTCAGGAGCCTCAGCCTGGCACAARGG[FAM-dT](THF)A [BHQ-dT] CATGAGAGCAGTGAATGA (C3-spacer) NS5 8750-8801 Note. *Probe modifications: FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; THF, tetrahydrofuran; BHQ, black hole quencher; C3-spacer, 3′ phosphate blocker. -

Targeted NS5 gene fragments were cloned into linearized pGEM-T Easy Vectors (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) with T4 DNA ligase. Linearized plasmid DNA template was recovered, purified, and enriched with MagicPure size-selection DNA beads according to the manufacturer's specifications. To recover RNA transcripts, the DNA templates were transcribed with T7 polymerase using the T7 High Efficiency Transcription Kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and treated with DNase I to remove any residual DNA. Subsequently, the RNA copy number was calculated according to a previously described method[25, 26]. The RNA transcripts were used to evaluate the sensitivity of the RT-RAA.

-

All viral RNA was extracted from cell cultures and tick specimens using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Dusseldorf, Germany) according to the manufacturer's specifications. The RT-RAA reaction was performed with an RT exo kit (Jiangsu Qitian Bio-technology, China), which mixed all the enzymes (SSB, 800 ng/μL; UvsX, 120 ng/μL; DNA polymerase, 30 ng/μL) for the reverse transcription and DNA amplification in lyophilized form in one tube. The reaction mixture contained 1 μL of RNA template, 25 μL of rehydration buffer, 16.7 μL of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) H2O, 2.1 μL of each primer (10 μmol/L), and 0.6 μL of probe. Finally, 47.5 μL of master mix/template solution was transferred to each lyophilized enzyme mix. Then, 2.5 μL of 280 mmol/L magnesium acetate was pipetted into each tube lid. The tube lids were closed carefully, vortexed briefly, and centrifuged simultaneously to trigger the RT-RAA reaction. The tubes were then transferred to an RAA fluorescence detection device QT-F1620 with FAM and HEX dual-channel detection equipment (Jiangsu Qitian Bio-technology, China) at 39 ℃ for 30 min. A negative control (nuclease-free water) was included in each run.

-

Dilution series with standard RNA transcripts ranging from 106 to 100 copies RNA/reaction and TBEV titers between 103 and 100 pfu per reaction were prepared and used in the real-time fluorescence detection assay to evaluate the sensitivity of the RT-RAA. Eight replicates were performed for each dilution. The limit of detection was calculated by probit analysis at 95% probability.

To test the specificity of this assay, cross- reactivity was examined with Japanese encephalitis virus, Culex flavivirus, West Nile virus, Zika virus, Yellow fever virus, Dengue virus (serotypes 2), Tahyna virus, Getah virus, Sindbis virus, and Kadipiro virus which preserved in our lab. The accuracy of the RT-RAA assay were performed with previous preserved tick samples and Taqman RT-PCR method[13, 27].

-

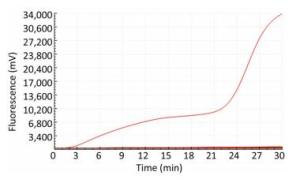

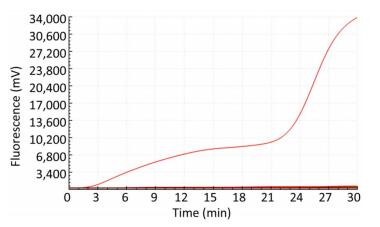

Only the TBEV RNA produced amplification signals, whereas none of the other arboviruses and no-template controls produced a positive amplification signal (Figure 1).

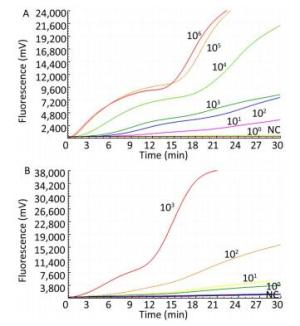

The sensitivity of the TBEV titers was determined by serial 10-fold dilution with concentrations ranging from 1 × 103 to 1 × 100 pfu per reaction (Figure 2). The limit of detection of the TBEV titers at 95% probability was 3 pfu per reaction (probit analysis, P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2). Similarly, the sensitivity for in vitro-transcribed RNAs was observed with serially diluted concentrations ranging from 1 × 106 to 1 × 100 copies per reaction (Figure 1). The limit of detection of the in vitro-transcribed RNAs at 95% probability was 20 copies per reaction (probit analysis, P ≤ 0.05) (Table 2).

Figure 2. Sensitivity of the RT-RAA assay for TBEV. A panel of serial 10-fold dilutions of (A) transcript RNA from 106 to 100 copies per reaction and (B) TBEV titers from 103 to 100 pfu per reaction was used to determine the sensitivity of the RT-RAA assay. NC, negative control.

Table 2. Assay Data Used for Probit Analysis to Calculate the Detection Limit of RT-RAA for TBEV

Concentration No. of Positive Samples /No. of Samples Tested by the RT-RAA Assays for Detection of TBEV TBEV titers* RNA transcripts** 103 8/8 8/8 102 8/8 8/8 101 8/8 6/8 100 6/8 0/8 Note. Each dilution was tested in a total of 8 replicates; Concentration unit: *pfu per reaction; **copies per reaction. -

TaqMan RT-qPCR was performed to verify the accuracy of our assay[13]. Ten batches of ticks collected in the Changbai Mountains in 2011 were used[27]; three of them were identified as positive for TBEV, which was consistent with the results of the quantitative real-time PCR assay. The results indicated that the sensitivity and accuracy of the RT-RAA assay developed in this study were the same as those of TaqMan RT-qPCR (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of TBEV Detection in Ticks Examined RT-RAA and TaqMan RT-PCR

Year Location Strain No. of Ticks TaqMan RT-PCR[13] RT-RAA 2011 Changbai JLP04 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP08[25] 10 Pos Pos 2011 Changbai JLP17 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP22 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP35[25] 10 Pos Pos 2011 Changbai JLP36 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP40[25] 10 Pos Pos 2011 Changbai JLP51 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP52 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JIP53 10 Neg Neg Note. Pos: positive; Neg: negative. -

Various recent publications have emphasized the importance of tick-borne viral encephalitis as a seasonal disease[28]. The increasing incidence of TBE, constant spread in endemic regions, and occurrence of new variants demonstrate the ongoing threat of TBEV[29]. TBE has a high mortality rate, and many survivors suffer from nerve sequelae for the rest of their lives[30, 31]. The severity of the clinical manifestations demonstrates the necessity for a rapid, accurate diagnosis.

The routine laboratory diagnosis of TBEV is based on the detection of IgM antibodies in blood or CSF using ELISA. However, because of the delayed onset of the IgM antibody response, especially in CSF, and the cross-reactions with other Flaviviruses, it is necessary to develop a method for the rapid detection of TBEV[32].

The highly sensitive and specific molecular diagnostic method for TBEV described in this study had a limit of detection as low as 20 copies or 26 pfu/mL per reaction. The lengths of the primers and probe (more than 30 base oligonucleotides) used for the RT-RAA assay enhanced the formation of an efficient recombinase-DNA complex, increasing the specificity of the RAA assay. Our RT-RAA assay can detect Far-Eastern TBEV in tick specimens within 30 minutes and with 100% consistency with real-time PCR results, which suggests that the RT-RAA assay developed here is potentially useful for clinical specimens and for analyzing the distribution of TBEV in samples from patients and animal hosts. The assay makes use of lyophilized pellets containing all the enzymes and a closed tube for fast, easy transportation (without the need for a cold chain) and operation, while minimizing the contamination risk. By contrast, RT-qPCR is usually more time-consuming, more expensive, and requires technical and instrumental support. Compared with other isothermal amplification techniques, such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), the primer design for RAA is simpler, and the cost of one reaction is lower.

The three subtypes of TBEV are named according to their main areas of circulation: the European, Siberian, and Far-Eastern subtypes. In China, the TBEV identified from patients and ticks was mainly the Far-Eastern subtype. The Siberian subtype was originally identified in Siberia, but its sequence has also been found in ticks collected in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (northwestern China). Therefore, a RT-RAA assay able to detect and differentiate all subtypes of TBE virus is needed in the future. The performance of the RAA assay could also be improved by using more and different specimens before applying it in clinical laboratories.

-

The RT-RAA assay developed is as good as an RT-qPCR assay, indicating that it is a valuable addition to the serological tests currently available for the diagnosis of TBE. This technique should attract more attention and undergo further development in the near future.

-

WANG Qian Ying, LI Fan, WANG Huan Yu and MA Xue Jun designed the study; WANG Qian Ying, LI Fan, SHEN Xin Xin performed the RT-RAA experiments; FU Shi Hong, LEI Wen Wen and HE Ying performed TBE virus culture; WANG Qian Ying, LI Fan, MA Xue Jun and LIANG Guo Dong contributed to drafting and editing the paper; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

-

All authors declare that they have no competing conflicts of interests, no competing financial interests

doi: 10.3967/bes2019.047

A Reverse-transcription Recombinase-aided Amplification Assay for the Rapid Detection of the Far-Eastern Subtype of Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus

-

Abstract:

Objective Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) is an emerging pathogen in Europe and North Asia that causes tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). A simple, rapid method for detecting TBEV RNA is needed to control this disease. Methods A reverse-transcription recombinase-aided amplification (RT-RAA) assay was developed. This assay can be completed in one closed tube at 39℃ within 30 minutes. The sensitivity and specificity of RT-RAA were validated using non-infectious synthetic RNA representing a fragment of the NS5 region of the wild-type (WT) TBEV genome and the Senzhang strain. Additionally, 10 batches of tick samples were used to evaluate the performance of the RT-RAA assay. Results The analytical limit of detection of the assay was 20 copies per reaction of the TBEV synthetic transcript and 3 plaque-forming units (pfu) per reaction of TBEV titers. With the specific assay, no signal due to other arboviruses was observed. Of the 10 batches of tick samples obtained from the Changbai Mountains of China, three were TBEV-positive, which was consistent with the results of the quantitative real-time PCR assay. Conclusion A rapid, highly sensitive, specific, and easy-to-use method was developed for the detection of the TBEV Far-Eastern subtype. -

Key words:

- Tick-borne encephalitis virus /

- Subtype /

- Far-eastern /

- Detection /

- RT-RAA

-

Table 1. Sequences of Primers and Probes for RT-RAA Assays for TBEV

Primers/Probes Sequence (5′-3′) Genomic Region Genomic Position Product Size (bp) TBE-F CCTTTGGACAGCAGCGAGTGTTCAARGAGAA NS5 8708-8739 TBE-R CTATGAAYTCCTCTCTGCTGCACATTCGTGG NS5 8836-8866 159 TBE-Probe* AGGCTCAGGAGCCTCAGCCTGGCACAARGG[FAM-dT](THF)A [BHQ-dT] CATGAGAGCAGTGAATGA (C3-spacer) NS5 8750-8801 Note. *Probe modifications: FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; THF, tetrahydrofuran; BHQ, black hole quencher; C3-spacer, 3′ phosphate blocker. Table 2. Assay Data Used for Probit Analysis to Calculate the Detection Limit of RT-RAA for TBEV

Concentration No. of Positive Samples /No. of Samples Tested by the RT-RAA Assays for Detection of TBEV TBEV titers* RNA transcripts** 103 8/8 8/8 102 8/8 8/8 101 8/8 6/8 100 6/8 0/8 Note. Each dilution was tested in a total of 8 replicates; Concentration unit: *pfu per reaction; **copies per reaction. Table 3. Comparison of TBEV Detection in Ticks Examined RT-RAA and TaqMan RT-PCR

Year Location Strain No. of Ticks TaqMan RT-PCR[13] RT-RAA 2011 Changbai JLP04 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP08[25] 10 Pos Pos 2011 Changbai JLP17 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP22 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP35[25] 10 Pos Pos 2011 Changbai JLP36 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP40[25] 10 Pos Pos 2011 Changbai JLP51 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JLP52 10 Neg Neg 2011 Changbai JIP53 10 Neg Neg Note. Pos: positive; Neg: negative. -

[1] Kaiser R. Tick-borne encephalitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2008; 22, 561-75, x. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.013 [2] Suzuki Y. Multiple transmissions of tick-borne encephalitis virus between Japan and Russia. Genes Genet Syst, 2007; 82, 187-95. doi: 10.1266/ggs.82.187 [3] Khasnatinov MA, Tuplin A, Gritsun DJ, et al. Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Structural Proteins Are the Primary Viral Determinants of Non-Viraemic Transmission between Ticks whereas Non-Structural Proteins Affect Cytotoxicity. PLoS One, 2016; 11, e0158105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158105 [4] Suss J. Epidemiology and ecology of TBE relevant to the production of effective vaccines. Vaccine, 2003; 21 Suppl 1, S19-35. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=b89260687343cec933fd264635d8b179 [5] Petri E, Gniel D, Zent O. Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) trends in epidemiology and current and future management. Travel Med Infect Dis, 2010; 8, 233-45. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.08.001 [6] Amicizia D, Domnich A, Panatto D, et al. Epidemiology of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) in Europe and its prevention by available vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2013; 9, 1163-71. doi: 10.4161/hv.23802 [7] Randolph SE. Tick-borne encephalitis incidence in Central and Eastern Europe:consequences of political transition. Microbes Infect, 2008; 10, 209-16. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.12.005 [8] Jaaskelainen AE, Tikkakoski T, Uzcategui NY, et al. Siberian subtype tickborne encephalitis virus, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis, 2006; 12, 1568-71. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060320 [9] He X, Zhao J, Fu S, et al. Complete Genomic Characterization of Three Tick-Borne Encephalitis Viruses Detected Along the China-North Korea Border, 2011. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2018; 18, 554-9. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2017.2173 [10] Fomsgaard A, Christiansen C, Bodker R. First identification of tick-borne encephalitis in Denmark outside of Bornholm, August 2009. Euro Surveill, 2009; 14. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=Open J-Gate000000969773 [11] Donoso Mantke O, Schadler R, Niedrig M. A survey on cases of tick-borne encephalitis in European countries. Euro Surveill, 2008; 13. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=Open J-Gate000000143658 [12] Mantke O D AK, Niedrig M. Serological versus PCR methods for the detection of tick-borne encephalitis virus infections in humans. Future Virology, 2007; 2, 565-72. doi: 10.2217/17460794.2.6.565 [13] Schwaiger M, Cassinotti P. Development of a quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay with internal control for the laboratory detection of tick borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) RNA. J Clin Virol, 2003; 27, 136-45. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00168-3 [14] Achazi K, Nitsche A, Patel P, et al. Detection and differentiation of tick-borne encephalitis virus subtypes by a reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR and pyrosequencing. J Virol Methods, 2011; 171, 34-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.09.026 [15] Ruzek D, Stastna H, Kopecky J, et al. Rapid subtyping of tick-borne encephalitis virus isolates using multiplex RT-PCR. J Virol Methods, 2007; 144, 133-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.04.010 [16] Zhang Y, Zhang C, Li B, et al. VSITA, an Improved Approach of Target Amplification in the Identification of Viral Pathogens. Biomed Environ Sci, 2018; 31, 272-9. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/bes201804003 [17] Wang J, Ke YH, Zhang Y, et al. Rapid and Accurate Sequencing of Enterovirus Genomes Using MinION Nanopore Sequencer. Biomed Environ Sci, 2017; 30, 718-26. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=bes201710003 [18] Wang CH, Nie K, Zhang Y, et al. An Improved Barcoded Oligonucleotide Primers-based Next-generation Sequencing Approach for Direct Identification of Viral Pathogens in Clinical Specimens. Biomed Environ Sci, 2017; 30, 22-34. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=bes201701003 [19] Lü Bei CH, YAN QingFeng, HUANG ZhenJu, et al. Recombinase-aid amplification:a novel technology of in vitro rapid nucleic acid amplification. SCIENTIA SINICA Vitae, 2010; 40, 983-8. [20] Zhang X, Guo L, Ma R, et al. Rapid detection of Salmonella with Recombinase Aided Amplification. J Microbiol Methods, 2017; 139, 202-4. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2017.06.011 [21] Chen C, Li XN, Li GX, et al. Use of a rapid reverse-transcription recombinase aided amplification assay for respiratory syncytial virus detection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2018; 90, 90-5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.10.005 [22] Yan TF, Li XN, Wang L, et al. Development of a reverse transcription recombinase-aided amplification assay for the detection of coxsackievirus A10 and coxsackievirus A6 RNA. Arch Virol, 2018; 163, 1455-61. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3734-9 [23] Gao X, Nasci R, Liang G. The neglected arboviral infections in mainland China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2010; 4, e624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000624 [24] Cao L, Fu S, Gao X, et al. Low Protective Efficacy of the Current Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine against the Emerging Genotype 5 Japanese Encephalitis Virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2016; 10, e0004686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004686 [25] Barros SC, Ramos F, Ze-Ze L, et al. Simultaneous detection of West Nile and Japanese encephalitis virus RNA by duplex TaqMan RT-PCR. J Virol Methods, 2013; 193, 554-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.07.025 [26] Shao N, Li F, Nie K, et al. TaqMan Real-time RT-PCR Assay for Detecting and Differentiating Japanese Encephalitis Virus. Biomed Environ Sci, 2018; 31, 208-14. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/bes201803004 [27] He X, Zhao J, Fu S, et al. Complete Genomic Characterization of Three Tick-Borne Encephalitis Viruses Detected Along the China-North Korea Border, 2011. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2018; 18, 554-9. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2017.2173 [28] Ruef C. Tick-borne viral encephalitis——the threat of summer. Infection, 2000; 28, 65-7. doi: 10.1007/s150100050048 [29] Dai X, Shang G, Lu S, et al. A new subtype of eastern tick-borne encephalitis virus discovered in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2018; 7, 74. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=10.1038/s41426-018-0081-6 [30] Kaiser R, Archelos-Garcia JJ, Jilg W, et al. Tick-borne Encephalitis (TBE). Neurology International Open, 2017; 1, E48-E55. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-103258 [31] Lindquist L, Vapalahti O. Tick-borne encephalitis. The Lancet, 2008; 371, 1861-71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60800-4 [32] Dumpis U, Crook D, Oksi J. Tick-borne encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis, 1999; 28, 882-90. doi: 10.1086/cid.1999.28.issue-4 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links