-

Globalization and international travel have increased the ability of persons to travel easily all over the world. The increasing frequency of emerging infectious diseases that spread internationally has produced serious health and economic impacts and global health security threats[1, 2]. In recorded human history, the global community has suffered from many shared infectious diseases, such as the 14th-century Black Death pandemics (bubonic/pneumonic plague) and the 1918 influenza pandemic, which caused 25–40 million and 50–100 million deaths, respectively[3, 4]. The global spread of newly emerging infectious diseases, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), H5N1 avian influenza, and 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza, has caused deaths and economic losses, and other adverse outcomes[5].

Foreign visitors to China have become more common, especially in recent years. The 6th national population census showed that there were an estimated 0.6 million foreign persons, amounting to 0.04% of the total population, living for more than 3 months in China[6]. According to the China Statistical Yearbook, the number of inbound tourists from overseas has grown from 20.2 million people in 2005 to 29.2 million people in 2017[7]. Multiple factors are associated with the risk and burden of infectious diseases among foreign persons, including the prevalence of these diseases in the countries of origin and destination, access to health services, cultural mentalities or social norms and individual behaviors[8-10]. In Finland, 90% of chronic hepatitis B, 60% of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and 58% of syphilis cases were diagnosed among individuals of foreign origin in 2016[11]. Approximately 70% of newly diagnosed UK tuberculosis (TB) cases and 60% of new HIV cases were found in migrants[12]. However, the epidemiological characteristics of infectious diseases of the foreigners in China is limited.

The National Notifiable Infectious Disease Reporting Information System (NNIDRIS) is currently the largest system for reporting infectious disease cases in China to help collect information on disease occurrence and epidemics and provides an early warning system for infectious disease outbreaks[13, 14]. Any person with notifiable infectious diseases, from Chinese citizens to Taiwan/Hong Kong/Macao residents or any other foreign person, who visits a health care facility (HCF), including an international HCF, is required to be reported. For practical surveillance purposes, the population under surveillance was divided into four types, including Chinese local residents, internal mobile population, Taiwan/Hong Kong/Macao residents and foreign nationals. The term ‘foreign cases’ in this paper refers to people who are captured in the NNIDRIS and identified as foreign nationals.

In this study, we assessed the epidemiological characteristics of 39 notifiable infectious diseases among foreign cases from 2004 to 2017 in China. The characterization of these data is aimed to support recommendations for the development of screening tests and improvement of early surveillance and warning for infectious diseases.

-

The Chinese government established the Notifiable Disease Reporting System for selected infectious diseases in the 1950s[15]. In 2004, this system was developed into the NNIDRIS, a web-based real-time reporting system, to improve the quality of case-based surveillance. The system serves all of China’s 1.3 billion people by relying on direct reporting from hospitals, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCs), clinics, communities, ports and customs, blood stations, and other health facilities at all levels that feed into an expanded CDC network. In 2007, it covered 96% of county- to provincial-level hospitals and 79% of township hospitals nationwide[16]. At the end of 2017, the coverage of county- to provincial-level increased to 98%, and township hospitals to 90%. NNIDRIS operates through administrative grading responsibility and territorial management.

This information platform gathered epidemiological information on 37 notifiable infectious diseases in 2004 and then increased to 39 after 2013. Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) and avian influenza H7N9 cases were included in 2008 and 2013, respectively[17-19]. A standard case report card for 39 notifiable infectious diseases is required to be completed and reported to the local CDC within the statutory time. CDC staffs at several levels are responsible for collecting data, detecting and analyzing possible epidemics of diseases, and, if necessary, following up actively these reported cases.

The foreign infectious disease cases has been included in the NNIDRIS from 2004 to the present. The reporting procedure for infectious disease among foreign cases was the same as that of in Chinese patients. We included all clinically diagnosed or laboratory confirmed notifiable infectious disease cases in the foreign population with illness onset during 2004–2017 from the NNIDRIS. Cases with non-notifiable infectious diseases or belonging to other three types of population were excluded. The epidemiological characteristics contained age, gender, occupation, date of onset, country of birth, the reporting provinces, and the diseases.

-

The epidemiological features of 39 infectious diseases found among foreign cases between 2004 and 2017 were described regarding spatial-temporal distribution in this study. We described seasonal distribution with a radar diagram based on monthly incident cases. Viral hepatitis was substratified into hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and hepatitis E for analysis. We used SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for data extracting, sorting, and cleaning. Disease maps of cumulative cases from 2004 to 2017 in China were visualized using ArcGIS 10.3 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA) based on provinces.

-

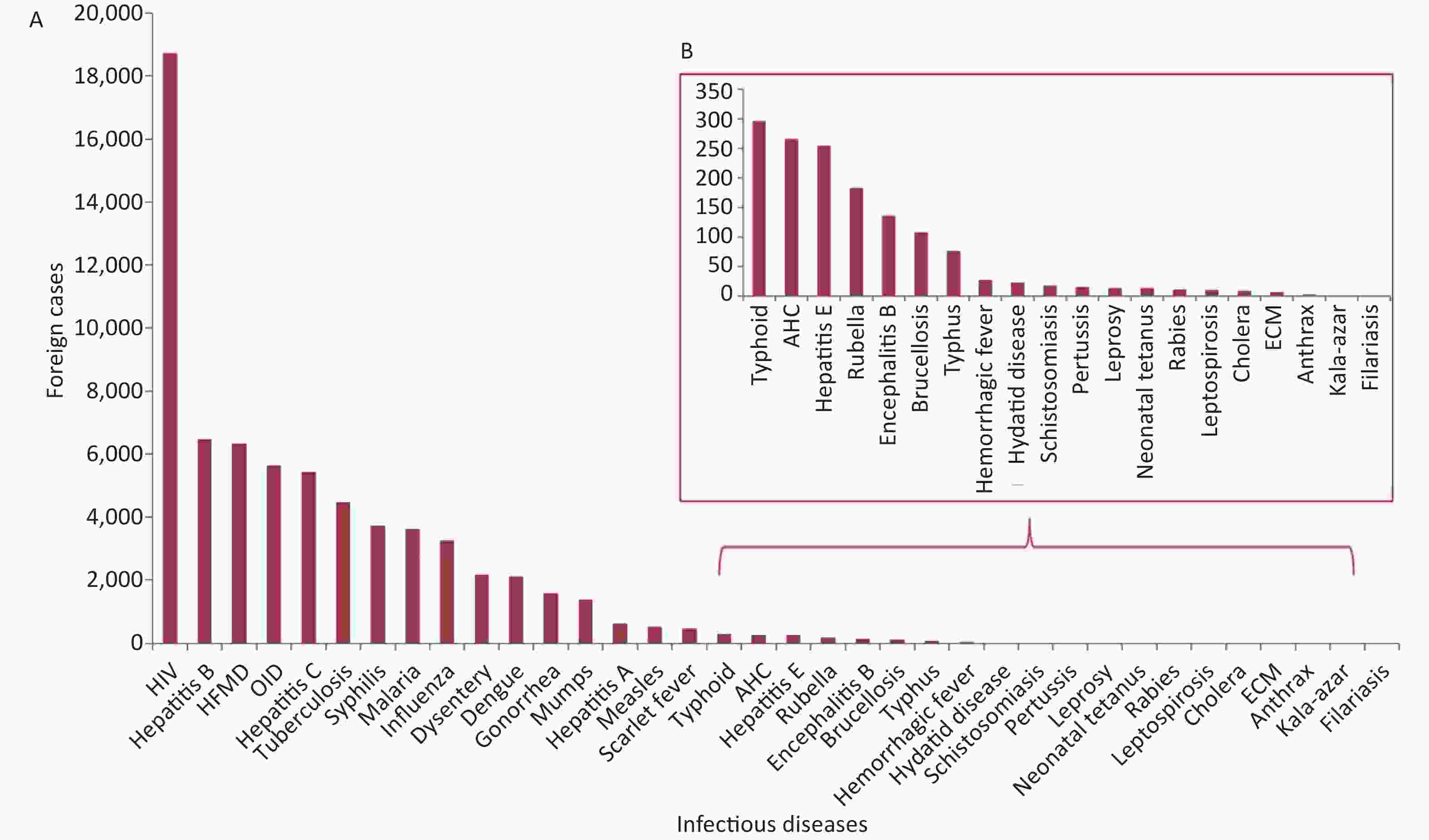

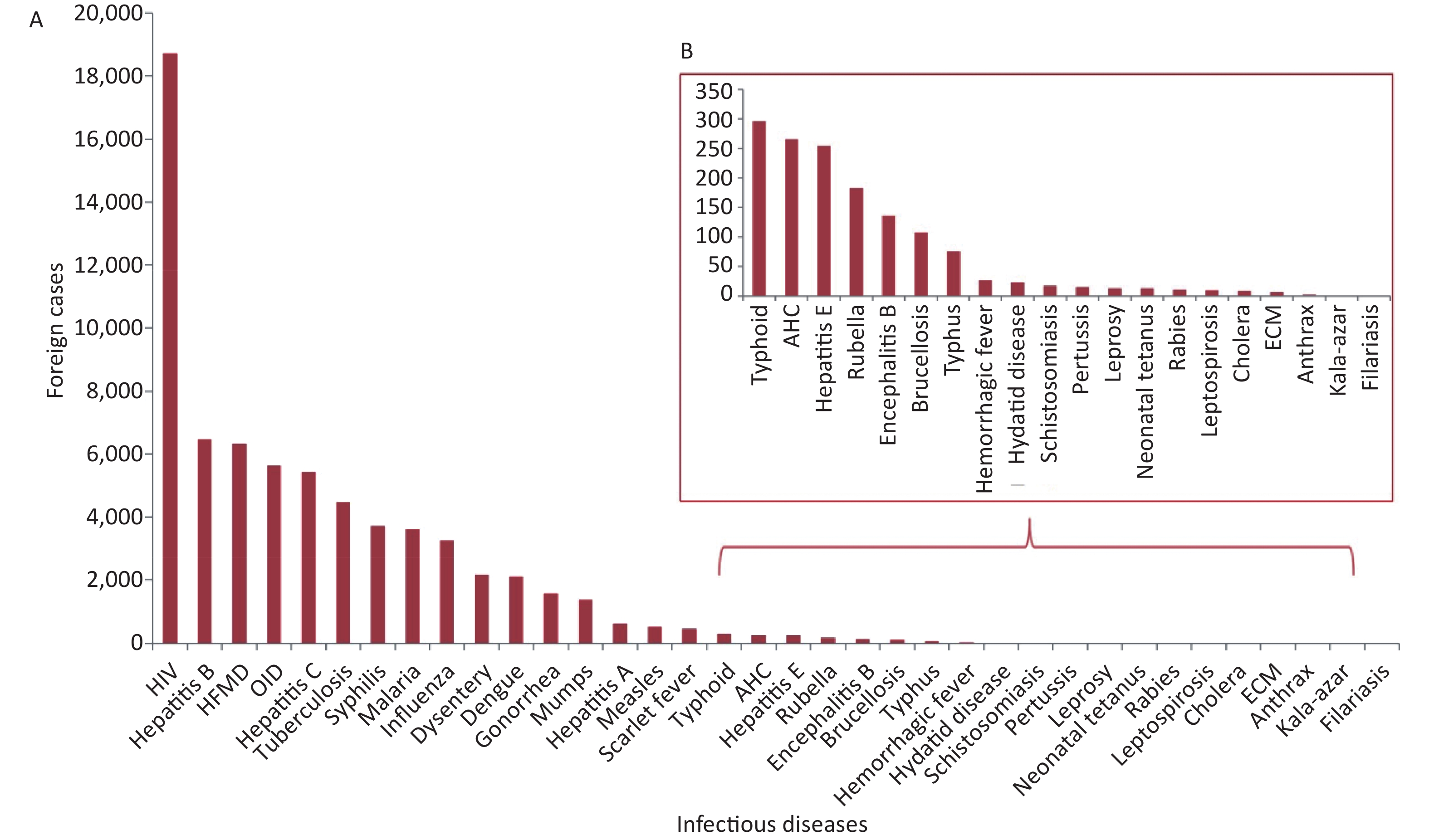

Between January 2004 and December 2017, a total of 33 notifiable infectious diseases out of 67,939 foreign cases of infectious disease were reported in China. No cases of the six notifiable infectious diseases were reported, including plague, avian influenza H7N9, SARS, diphtheria, poliomyelitis, and human infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza. The reported infectious diseases with the highest number of cases were HIV (18,713), hepatitis B (6,461), HFMD (6,327), which together accounted for 46.37% (31,501) of the overall patients. The most common transmission route of infectious disease was sexual or blood contact with 52.83%; intestinal transmission ranked second, accounting for 22.55%, and respiratory disease third with 15.16% (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1 available in www.besjournal.com).

Table 1. The number of all infectious disease cases in the foreign population reported in China during 2004–2017

Diseases 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Total HIV 433 657 923 789 1,151 1,074 1,066 1,462 1,637 1,785 1,785 1,979 2,125 1,847 18,713 Hepatitis B 33 353 566 576 565 488 462 477 462 444 468 485 619 463 6,461 HFMD 1 14 33 92 208 313 554 554 621 670 865 652 931 819 6,327 OID 2 231 324 365 455 372 506 491 446 556 415 389 462 617 5,631 Hepatitis C 20 186 396 517 445 375 429 476 464 418 339 395 502 466 5,428 Tuberculosis 23 163 206 326 296 356 337 355 317 312 367 431 494 493 4,476 Syphilis 1 103 172 224 270 259 215 273 281 315 356 311 444 495 3,719 Malaria 0 136 573 430 308 290 438 331 265 210 144 143 167 186 3,621 Influenza 0 14 19 15 13 249 23 36 390 289 258 224 819 893 3,242 Dysentery 0 213 253 288 229 204 167 159 139 117 105 116 91 95 2,176 Dengue 0 19 18 10 50 17 36 40 33 113 171 365 226 1,008 2,106 Gonorrhea 2 111 123 145 138 106 86 82 90 98 83 102 168 240 1,574 Mumps 0 83 89 99 102 121 120 134 123 128 94 71 97 113 1,374 Hepatitis A 0 28 39 34 63 64 45 44 59 61 59 60 42 31 629 Measles 0 46 29 58 54 41 20 21 94 38 34 18 19 51 523 Scarlet fever 0 13 26 22 19 13 29 52 45 31 53 53 50 62 468 Typhoid 0 14 18 38 34 19 23 17 27 25 18 27 16 20 296 AHC 0 2 7 20 22 10 75 12 15 24 30 23 15 11 266 Hepatitis E 1 10 16 21 18 8 8 25 29 20 12 24 38 25 255 Rubella 0 3 8 20 35 18 15 31 18 12 8 11 4 0 183 Encephalitis B 1 2 1 8 8 12 15 17 16 21 11 5 10 9 136 Brucellosis 0 0 2 8 8 11 12 7 6 8 11 14 13 8 108 Typhus 0 0 2 5 9 2 5 5 14 9 9 10 4 2 76 Hemorrhagic fever 0 2 4 3 2 1 1 2 2 6 2 0 2 0 27 Hydatid disease 0 0 0 4 3 2 4 3 1 0 1 1 3 1 23 Schistosomiasis 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 3 2 0 2 7 1 0 18 Pertussis 0 0 0 1 2 3 0 2 0 1 0 2 3 2 16 Leprosy 0 0 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 3 0 0 0 13 Neonatal Tetanus 0 2 2 1 1 0 0 0 2 3 2 0 0 0 13 Rabies 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 2 2 2 1 1 1 11 Leptospirosis 0 0 2 1 0 1 0 2 3 0 0 1 0 0 10 Cholera 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 2 0 2 0 0 0 0 9 ECM 0 2 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 7 Anthrax 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 Kala-azar 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Filariasis 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Total 517 2,407 3,855 4,123 4,515 4,430 4,697 5,118 5,604 5,719 5,707 5,920 7,367 7,958 67,939 Note. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; ECM, epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; AHC, acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis; dysentery, bacillary dysentery and amoebic dysentery; typhoid, Typhoid and paratyphoid.

Figure S1. Spectrum and ranking of infectious diseases in terms of the number of foreign cases with infectious disease, China, 2004–2017. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; ECM, epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis.; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; AHC, acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis.

-

The number of infectious diseases among foreign cases reported in China showed an increasing trend between 2004 and 2017 from 517 to 7,958, with an average annual increase of 23.40%. HIV increased yearly with a peak of 2,125 cases in 2016. HFMD and syphilis also showed an upward trend, whereas malaria and dysentery cases decreased during 2004–2017. The reported cases of dengue dramatically increased after 2012 and reached a peak with 1,008 cases in 2017, and influenza in 2016 and 2017 cases were reported three times higher than in earlier years. Hepatitis C, hepatitis B and infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid (OID) cases remained consistent but with a slight rise in TB cases during 2004–2017.

The ranking of the top 10 reportable infectious diseases has changed frequently over the years. HIV has always been the leading infectious disease and ranked first, whereas HFMD, since being included in the notifiable infectious disease list, has replaced hepatitis B as second from 2010 to 2016. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C, which ranked in the top five most common infectious diseases during 2004–2016, reached the lowest positions at ninth and eighth in 2017, respectively, whereas the rank of dengue and seasonal influenza rose to second and third, respectively. Dysentery and malaria, which ranked fourth in 2005 and second in 2006, respectively, showed a descending trend and dropped out of the top 10 in 2012 and 2015, respectively. Gonorrhea showed a rank decline in 2004–2008 but was back to the top 10 in 2016–2017 (Table 1).

-

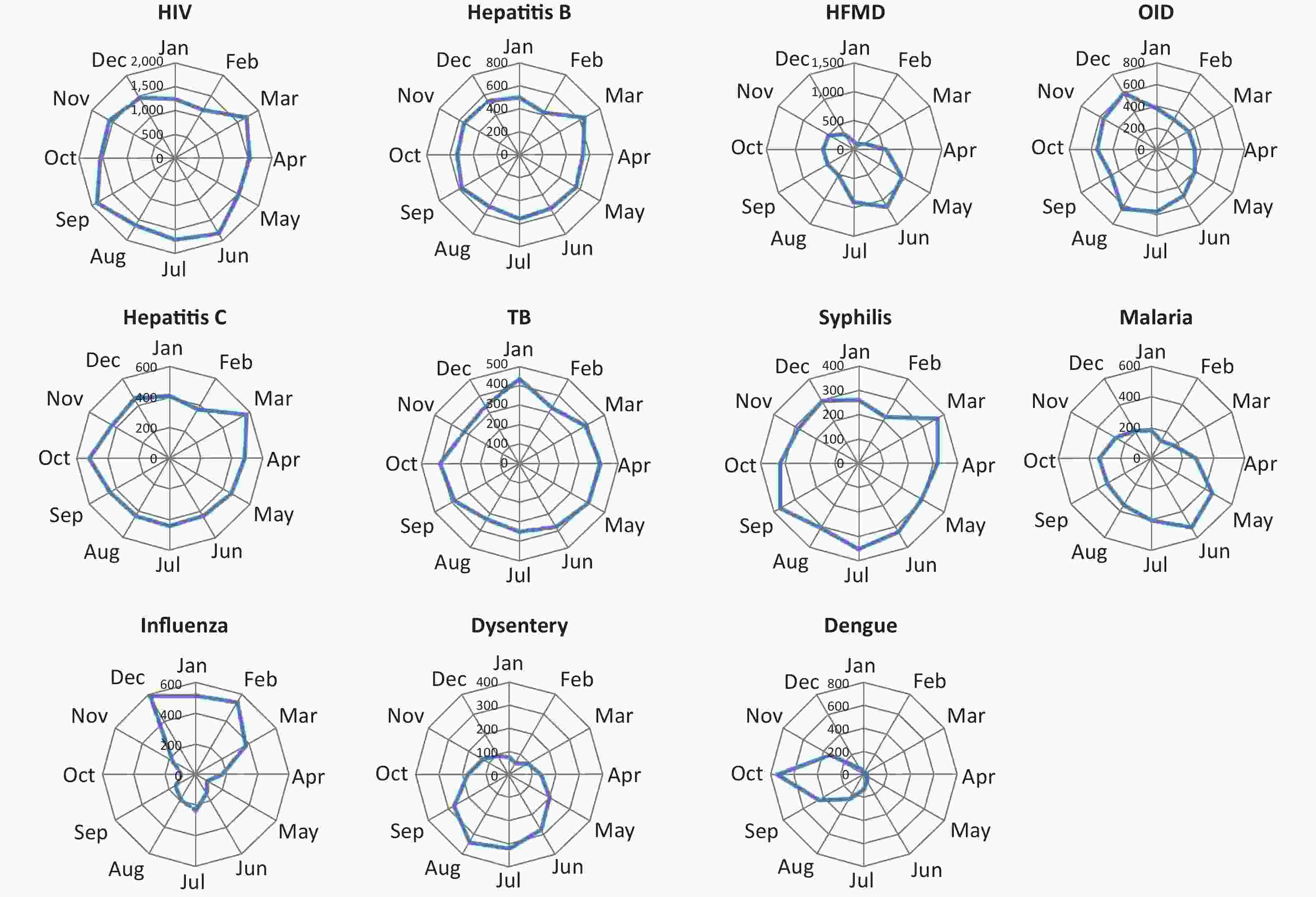

Significant seasonal features were noted for several infectious diseases, including HFMD, OID, malaria, influenza, dysentery, and dengue. Sexual or blood contact diseases, including HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis, have not exhibited obvious seasonality. Higher cases of HFMD were seen during May to July. Influenza was reported mainly during December to March. All the malaria cases were reported during April to July, whereas occurrence of dengue fever usually peaked in October (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S2 available in www.besjournal.com).

Table 2. Epidemiological characteristics of the most common infectious disease cases in the foreign population in China (2004–2017)

Disease Sex, no. (%) Mean age, year (range) Seasonal feature Main reporting provinces/cities (%) Male Female HIV 11,992 (64.08) 6,721 (35.92) 30 (25–37) Not significant Yunnan (56.13) Hepatitis B 4,146 (64.17) 2,315 (35.83) 38 (27–51) Not significant Inner Mongolia (16.22), Yunnan (15.71) HFMD 3,752 (59.30) 2,575 (40.70) 2 (1–4) May to July Shanghai (22.93) OID 3,504 (62.23) 2,127 (37.77) 16 (1–38) July to December Beijing (33.30) Hepatitis C 3,031 (55.84) 2,397 (44.16) 48 (37–58) Not significant Yunnan (32.89), Inner Mongolia (29.68) Tuberculosis 2,991 (66.82) 1,485 (33.18) 35 (25–51) Not significant Yunnan (53.66) Syphilis 2,164 (58.19) 1,555 (41.81) 36 (27–50) Not significant Guangdong (15.65), Yunnan (14.14) Malaria 2,734 (75.50) 887 (24.50) 26 (19–36) April to July Yunnan (75.75) Influenza 2,001 (61.72) 1,241 (38.28) 20 (6–37) December to March Beijing (55.21) Dysentery 1,359 (62.45) 817 (37.55) 24 (7–40) May to October Beijing (39.66) Dengue 1,056 (50.14) 1,050 (49.86) 28 (19–41) September to November Yunnan (83.14) Note. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; dysentery, bacillary dysentery and amoebic dysentery.

Figure S2. Seasonal distribution of main infectious diseases among the foreign cases in China, 2004–2017. In the radar diagram, the circumference represents 12 months followed in a clockwise direction, and the radius represents incident cases. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; TB, tuberculosis.

-

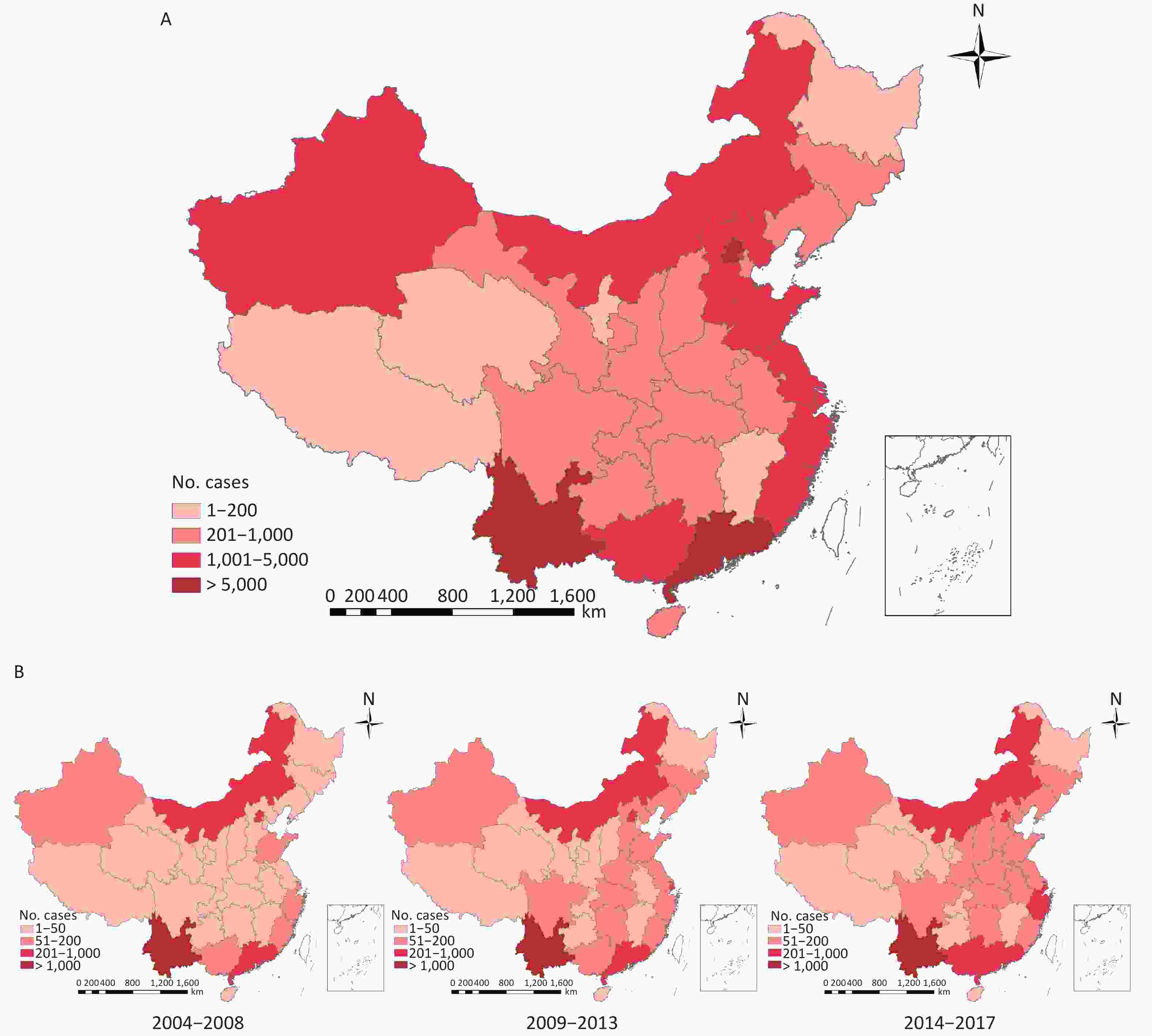

All 31 provinces reported foreign cases of infectious disease during 2004–2017. The trends of the annual average number of cases in most provinces for 2004–2008, 2009–2013, and 2014–2017 were stable or showed an increase. Coastal provinces had a higher proportion of cases than inland areas. Yunnan, Beijing, and Guangdong provinces accounted for the highest cumulative number of foreign cases at 34.89%, 11.89%, and 10.23%, respectively.

The highest number of reports of infectious diseases was in Yunnan province, with HIV accounting for 56.13%, dengue 83.14%, malaria 75.75%, TB 53.66%, and hepatitis C 32.89%. OID, dysentery, and influenza were mainly concentrated in Beijing. HFMD cases were collected most frequently from Shanghai in early periods, but after introduction into the NNIDRIS, the cases showed an increase spread among the 31 provinces. The number of malaria cases in Yunnan has decreased from 256 cases per year in 2004–2008 to 51 cases per year in 2014–2017, whereas a slow increase was observed in Zhejiang, Fujian, and other southeastern provinces. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C were centrally distributed in Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, Guangdong, and Xinjiang provinces. Cases of the two diseases had a substantial decrease in Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang but increase in Guangdong and Yunnan provinces. Syphilis was commonly reported in Guangdong and Inner Mongolia but had a significant increase from 3 to 96 cases in Yunnan in 2014–2017 (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of infectious disease cases in the foreign population averaged annual numbers in each province of China: 2004–2008, 2009–2013, and 2014–2017. (A) Geographic distribution of total cases from 2004 to 2017. (B) Geographic distribution of averaged annual numbers of foreign cases: 2004–2008, 2009–2013, and 2014–2017.

-

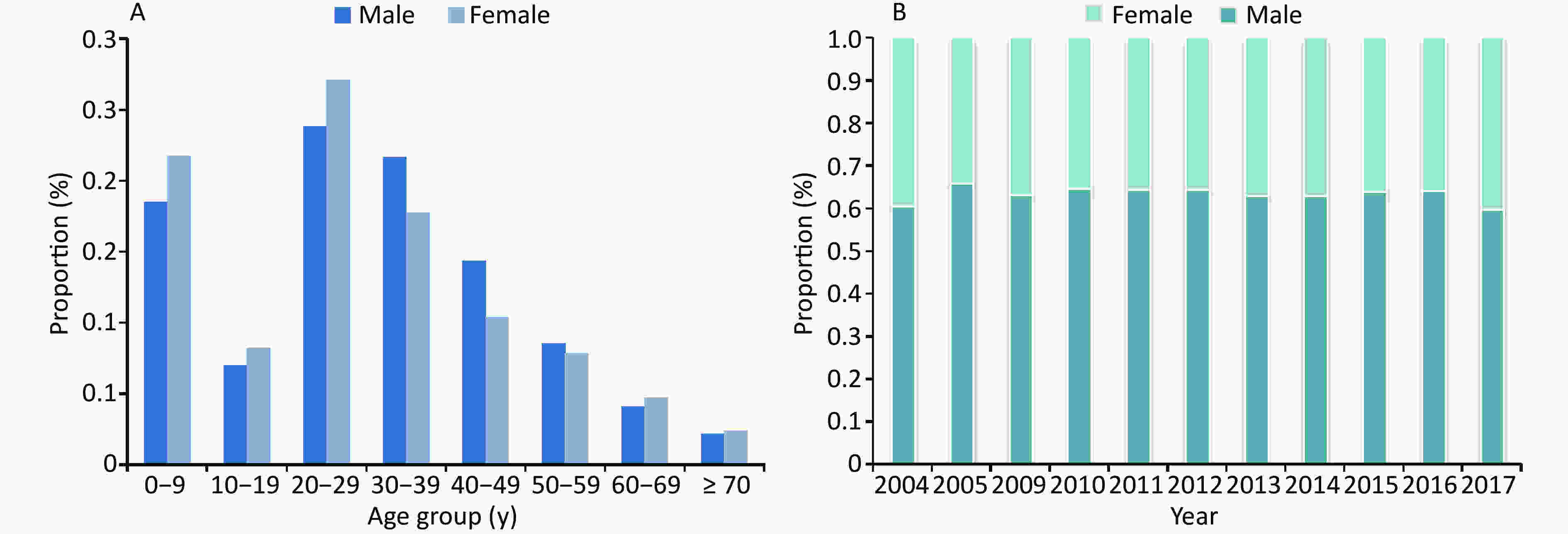

Among all foreign cases reported during 2004–2017, there was a larger proportion of male than female cases, with a sex ratio of 1.7:1. By profession, most patients were farmers (25.20%), followed by housekeeping staff (9.48%) and businessmen (8.40%). Foreign cases were mainly reported from county- to provincial-level hospitals (62.56%) and local CDCs (17.74%). The most common age distributions were 1–9 and 20–39 years, with proportions of 19.67% and 45.22%, respectively. The infectious disease cases with a median age of 30 years and above included HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, TB, and syphilis. The median age of patients with HFMD was 2 years, OID 16 years, and influenza 20 years (Table 2 and Figure 2).

-

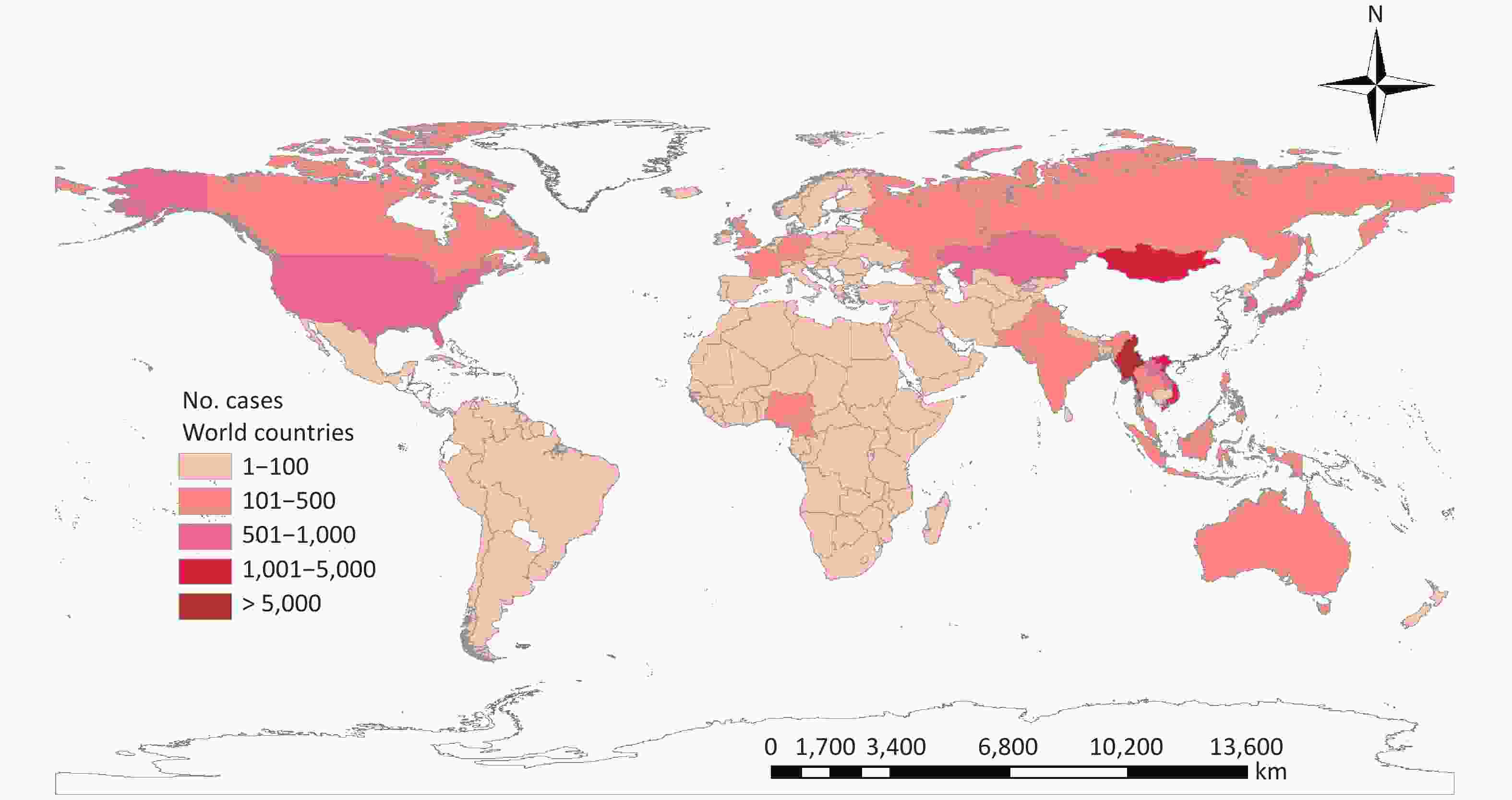

Infectious diseases among foreign cases have been reported to come from 146 countries of five continents during 2014–2017. Asian origin foreigners accounted for the highest cumulative number of foreign cases (41.65%), covering nearly all infectious diseases. Unfortunately, the countries of birth for 51.55% of infectious disease cases was unavailable, some biases existed.

Malaria cases were mainly from Asia (76.7%), followed by Africa (16.0%). Asian origin cases had a substantial decrease from 252 cases per year in 2004–2008 to 72 cases per year in 2013–2017. However, African origin cases were increasingly reported in Beijing, Guangdong, Zhejiang, and other southeastern provinces in recent years.

Myanmar was the main country of origin for dengue (1,650, 78.35%), malaria (2,628, 72.58%), HIV (8,984, 48.01%), TB (1,895, 42.34%), and hepatitis C (1,524, 28.08%), which were mainly reported in Yunnan province. Mongolia was the main country of origin for hepatitis C (1,285, 23.67%) and hepatitis B (718, 11.11%) and most of these cases were reported in Inner Mongolia and Beijing. However, hepatitis B and hepatitis C had a substantial decrease in Mongolia cases from 98 to 7 cases and 144 to 19 cases per year, respectively, whereas, Myanmar cases remained consistent (Figure 3).

-

This is the first long-term report on the epidemiological characteristic of notifiable infectious diseases among foreigners in China from 2004 to 2017. Our findings showed that the number of foreign patients with infectious diseases reported in China has increased yearly, especially in HIV, HFMD, syphilis, influenza and dengue. The overall increasing rate is higher than 4.62% of infectious diseases in Chinese cases. The highest number of infectious disease reports was HIV, Hepatitis B, and HFMD, which is different from Chinese cases[20]. Foreign cases in China can have unique spatial-temporal distribution of reportable infectious diseases.

In china, the large number of foreign cases of the infectious diseases reported could be related to the high volume and frequency of foreign population movements in provinces near the border like Yunnan, Inner mongolia and Xinjiang, or with the convenient transportation like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong. In these regions, an interaction of factors could favour development and prevalence of different infectious diseases, including climate and environment, socioeconomic, convenient transportation, sanitary condition and the prevention and control measure of infectious diseases among provinces.

HIV was the most commonly reported infectious disease among foreign cases with an annual ascending trend during 2004–2017. However, the prevalence of HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in China was 0.037% in 2014, which is significantly lower than that in most countries of the world[21, 22]. In our study, we found that most of foreign HIV cases were from Yunnan province, which was consistent with that of in Chinese cases[23]. Yunnan was located in the Greater Mekong Subregion with proximity to Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam, which was the epicenter of Asia’s HIV/AIDS pandemic. Commercial sex and illicit drug abuse for a long time in this region facilitated the prevalence and spread of HIV/AIDS among Chinese people as well as foreigners[24].

There was a relatively high endemic of viral hepatitis in China with one-third of chronic HBV and 7% HCV of world’s patients, compared with a low prevalence in western Europe and North America[25, 26]. However, the risk of transmission to foreigners is likely to be low since HBV and HCV are not transmitted through casual contact. HBV and HCV among foreign cases had a decrease in Beijing and Inner Mongolia, which probably was associated with a decline in sero-prevalence of viral hepatitis in Mongolian population as Mongolian government followed a sequential approach to financing its hepatitis response since 1990[27]. In contrast, Yunnan and Guangdong cases had an increase, which deserved a further study. Effective protective measures should be recommended for foreigners coming to China, including Hepatitis B vaccination and avoiding blood exposure.

A substantial decline of malaria cases was found among foreign cases, especially cases from Southeast Asia, partly due to the effective prevention and control of malaria in cross-border regions of Yunnan[28]. In China, malaria in indigenous cases had decreased and there was no locally acquired infection reported for the first time in 2017[29, 30]. However, imported malaria, especially in Chinese migrant workers and travelers from high prevalence countries, has become a significant concern in China in recent years[31]. Our study indicated foreign malaria cases from Africa had an increase, which was consistent with the findings in Chinese migrant workers[32]. Specific strategies and measures such as improving sanitary condition and provision of healthcare should target these people.

Dengue outbreaks remains low in China, especially compared with tropical and subtropical areas such as southeast Asia[33, 34]. In the past few years, however, dengue had a great effect on southern China[35, 36]. Chinese cases mainly predominated in Guangdong, especially a pandemic in 2014, whereas, foreign cases are more seen in Yunnan, centrally in 2017[37]. There seemed to be a weak correlation between foreign and Chinese cases in prevalence of dengue in China. Unfortunately, in this study, we couldn’t acquire possible source of transmission among these foreign cases, but Myanmar origins cases should be concerned, as they accounted for the largest number of foreign dengue cases in China.

Our findings indicated that foreign infectious disease cases were more common among male adults and Asian origins, which was consistent with the demographic characteristic of foreigners entering China. Notably, a large proportion of foreign children younger than 10 years old were at risk of contracting infectious diseases. Large outbreaks of HFMD are common in Chinese children[38]. Our data suggested foreign HFMD cases among provinces had a rising epidemic similar to the prevalence in Chinese children. which is attributed to its possible spread by direct contact. Over 95% of cases of childhood infectious disease are hindered by vaccines[39]. However, policies and strategies regarding vaccination programs for foreign children in China have not been introduced and formulated. Vaccination and related health care are therefore important issues for the health of foreign children living in China.

In the context of frequent international population movement, several of these strategies can be readily adopted. (i) Targeted surveillance in foreign populated areas for foreigners can serve as a front-line defense to identify the possible infected population and potential transmission of infectious disease. It is necessary to add related contents about foreign patients to the existing surveillance system, including passport, nationals, and other individual information. That will help conduct an in-depth study of infectious diseases, explore relevant factors, and control them. (ii) Public health officials and primary clinicians need to play an active role in identifying cases with new and emerging infections from other countries and implement related measures to limit or prevent the spread of diseases. (iii) Immunization policy, combined with financing and providing immunization access for at-risk individuals and regions, should be formulated and implemented, which could reduce the spread of infectious disease. (iv) The effective integration of foreign population into the local healthcare system ensures that cases are diagnosed and treated in time, which helps to minimize their vulnerability and ensure effective access to health care and support.

There were some limitations to this study. First, the number and accuracy of case reporting may be influenced by screening intensity, coverage rate, availability of health facilities, and laboratory diagnostics. Second, foreign personnel exchanges are complex, and few denominator data were used to calculate the rates of infectious diseases, so conclusions are limited. Third, our data were based on 39 notifiable infectious diseases reported through the NNIDRIS. Emerging infectious diseases such as Zika virus and MERS were not included in the analysis. Fourth, Information on source of infection and half of countries of birth for foreign cases are not available from NNIDRIS. it is therefore not possible to draw conclusions about the occurrence of these diseases among foreign cases.

-

The foreign cases in China showed a unique epidemiological characteristic of notifiable infectious diseases between 2004 and 2017. Infectious diseases were more frequent in male than females at age of 20–39 years. The majority of infectious diseases, including HIV, HFMD, syphilis, influenza, and dengue, showed an increase over the period studied, whereas malaria and dysentery cases had a decrease. This study highlighted Yunnan, Beijing, and Guangdong were provinces with the highest number of infectious diseases among foreign cases. More frequent exchanges between people on an international level have increased the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases globally. Our research provides data for tackling challenges in the prevention and control of global infectious diseases.

-

We thank our colleagues and healthcare workers who contributed to the project from National Center for Public Health Surveillance and Information Service, Department of Infectious Disease Control and Prevention and CDCs at all levels for data collection and review.

-

WU Yue collected, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. LI Zhen Jun and YU Shi Cheng have contributed in the analysis of data. CHEN Liang, WANG Ji Chun, QIN Yu, and SONG Yu Dan have contributed in data collection process and manuscript edition. George F. GAO and DONG Xiao Ping conceived the concept and design. WANG Li Ping, ZHANG Qun, and HE Guang Xue designed the study and revised the manuscript.

-

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

doi: 10.3967/bes2020.057

Epidemiological Characteristics of Notifiable Infectious Diseases among Foreign Cases in China, 2004–2017

-

Abstract:

Objective We aimed to assess the features of notifiable infectious diseases found commonly in foreign nationals in China between 2004 and 2017 to improve public health policy and responses for infectious diseases. Methods We performed a descriptive study of notifiable infectious diseases among foreigners reported from 2004 to 2017 in China using data from the Chinese National Notifiable Infectious Disease Reporting System (NNIDRIS). Demographic, temporal-spatial distribution were described and analyzed. Results A total of 67,939 cases of 33 different infectious diseases were reported among foreigners. These diseases were seen in 31 provinces of China and originated from 146 countries of the world. The infectious diseases with the highest incidence number were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) of 18,713 cases, hepatitis B (6,461 cases), hand, foot, and mouth disease (6,327 cases). Yunnan province had the highest number of notifiable infectious diseases in foreigners. There were different trends of the major infectious diseases among foreign cases seen in China and varied among provinces. Conclusions This is the first description of the epidemiological characteristic of notifiable infectious diseases among foreigners in China from 2004 to 2017. These data can be used to better inform policymakers about national health priorities for future research and control strategies. -

S1. Spectrum and ranking of infectious diseases in terms of the number of foreign cases with infectious disease, China, 2004–2017. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; ECM, epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis.; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; AHC, acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis.

S2. Seasonal distribution of main infectious diseases among the foreign cases in China, 2004–2017. In the radar diagram, the circumference represents 12 months followed in a clockwise direction, and the radius represents incident cases. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; TB, tuberculosis.

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of infectious disease cases in the foreign population averaged annual numbers in each province of China: 2004–2008, 2009–2013, and 2014–2017. (A) Geographic distribution of total cases from 2004 to 2017. (B) Geographic distribution of averaged annual numbers of foreign cases: 2004–2008, 2009–2013, and 2014–2017.

Table 1. The number of all infectious disease cases in the foreign population reported in China during 2004–2017

Diseases 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Total HIV 433 657 923 789 1,151 1,074 1,066 1,462 1,637 1,785 1,785 1,979 2,125 1,847 18,713 Hepatitis B 33 353 566 576 565 488 462 477 462 444 468 485 619 463 6,461 HFMD 1 14 33 92 208 313 554 554 621 670 865 652 931 819 6,327 OID 2 231 324 365 455 372 506 491 446 556 415 389 462 617 5,631 Hepatitis C 20 186 396 517 445 375 429 476 464 418 339 395 502 466 5,428 Tuberculosis 23 163 206 326 296 356 337 355 317 312 367 431 494 493 4,476 Syphilis 1 103 172 224 270 259 215 273 281 315 356 311 444 495 3,719 Malaria 0 136 573 430 308 290 438 331 265 210 144 143 167 186 3,621 Influenza 0 14 19 15 13 249 23 36 390 289 258 224 819 893 3,242 Dysentery 0 213 253 288 229 204 167 159 139 117 105 116 91 95 2,176 Dengue 0 19 18 10 50 17 36 40 33 113 171 365 226 1,008 2,106 Gonorrhea 2 111 123 145 138 106 86 82 90 98 83 102 168 240 1,574 Mumps 0 83 89 99 102 121 120 134 123 128 94 71 97 113 1,374 Hepatitis A 0 28 39 34 63 64 45 44 59 61 59 60 42 31 629 Measles 0 46 29 58 54 41 20 21 94 38 34 18 19 51 523 Scarlet fever 0 13 26 22 19 13 29 52 45 31 53 53 50 62 468 Typhoid 0 14 18 38 34 19 23 17 27 25 18 27 16 20 296 AHC 0 2 7 20 22 10 75 12 15 24 30 23 15 11 266 Hepatitis E 1 10 16 21 18 8 8 25 29 20 12 24 38 25 255 Rubella 0 3 8 20 35 18 15 31 18 12 8 11 4 0 183 Encephalitis B 1 2 1 8 8 12 15 17 16 21 11 5 10 9 136 Brucellosis 0 0 2 8 8 11 12 7 6 8 11 14 13 8 108 Typhus 0 0 2 5 9 2 5 5 14 9 9 10 4 2 76 Hemorrhagic fever 0 2 4 3 2 1 1 2 2 6 2 0 2 0 27 Hydatid disease 0 0 0 4 3 2 4 3 1 0 1 1 3 1 23 Schistosomiasis 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 3 2 0 2 7 1 0 18 Pertussis 0 0 0 1 2 3 0 2 0 1 0 2 3 2 16 Leprosy 0 0 1 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 3 0 0 0 13 Neonatal Tetanus 0 2 2 1 1 0 0 0 2 3 2 0 0 0 13 Rabies 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 2 2 2 1 1 1 11 Leptospirosis 0 0 2 1 0 1 0 2 3 0 0 1 0 0 10 Cholera 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 2 0 2 0 0 0 0 9 ECM 0 2 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 7 Anthrax 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 Kala-azar 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Filariasis 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Total 517 2,407 3,855 4,123 4,515 4,430 4,697 5,118 5,604 5,719 5,707 5,920 7,367 7,958 67,939 Note. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; ECM, epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; AHC, acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis; dysentery, bacillary dysentery and amoebic dysentery; typhoid, Typhoid and paratyphoid. Table 2. Epidemiological characteristics of the most common infectious disease cases in the foreign population in China (2004–2017)

Disease Sex, no. (%) Mean age, year (range) Seasonal feature Main reporting provinces/cities (%) Male Female HIV 11,992 (64.08) 6,721 (35.92) 30 (25–37) Not significant Yunnan (56.13) Hepatitis B 4,146 (64.17) 2,315 (35.83) 38 (27–51) Not significant Inner Mongolia (16.22), Yunnan (15.71) HFMD 3,752 (59.30) 2,575 (40.70) 2 (1–4) May to July Shanghai (22.93) OID 3,504 (62.23) 2,127 (37.77) 16 (1–38) July to December Beijing (33.30) Hepatitis C 3,031 (55.84) 2,397 (44.16) 48 (37–58) Not significant Yunnan (32.89), Inner Mongolia (29.68) Tuberculosis 2,991 (66.82) 1,485 (33.18) 35 (25–51) Not significant Yunnan (53.66) Syphilis 2,164 (58.19) 1,555 (41.81) 36 (27–50) Not significant Guangdong (15.65), Yunnan (14.14) Malaria 2,734 (75.50) 887 (24.50) 26 (19–36) April to July Yunnan (75.75) Influenza 2,001 (61.72) 1,241 (38.28) 20 (6–37) December to March Beijing (55.21) Dysentery 1,359 (62.45) 817 (37.55) 24 (7–40) May to October Beijing (39.66) Dengue 1,056 (50.14) 1,050 (49.86) 28 (19–41) September to November Yunnan (83.14) Note. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HFMD, hand, foot, and mouth disease; OID, infectious diarrheal diseases other than cholera, bacterial and amoebic dysentery, typhoid, and paratyphoid; dysentery, bacillary dysentery and amoebic dysentery. -

[1] Castelli F, Sulis G. Migration and infectious diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2017; 23, 283−9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.012 [2] Gushulak BD, Macpherson DW. Globalization of infectious diseases: the impact of migration. Clin Infect Dis, 2004; 38, 1742−8. doi: 10.1086/421268 [3] Morens DM, Folkers GK, Fauci AS. Emerging infection: a perpetual challenge. Lancet Infect Dis, 2008; 8, 710−9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70256-1 [4] Johnson NP, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 'Spanish' influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med, 2002; 76, 105−15. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2002.0022 [5] Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging infectious diseases: threats to human health and global stability. PLoS Pathog, 2013; 9, e1003467. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003467 [6] National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2010 population census. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/left.htm. [2019-4-30] (In Chinese) [7] National Bureau of Statistics of China. China statistical yearbook. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/Statisticaldata/AnnualData. [2019-4-30] [8] Seedat F, Hargreaves S, Nellums LB, et al. How effective are approaches to migrant screening for infectious diseases in Europe? A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis, 2018; 18, e259−71. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30117-8 [9] Seedat F, Hargreaves S, Friedland JS. Engaging new migrants in infectious disease screening: a qualitative semi-structured interview study of UK migrant community health-care leads. PLoS One, 2014; 9, e108261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108261 [10] Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Hossain M. Migration and health: a framework for 21st century policy-making. PLoS Med, 2011; 8, e1001034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001034 [11] Jaakola S, Lyytikäinen O, Huusko S, et al. infectious diseases in Finland in 2016. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL), 2017; 5. [12] Wagner KS, Lawrence J, Anderson L, et al. Migrant health and infectious diseases in the UK: findings from the last 10 years of surveillance. J Public Health (Oxf), 2014; 36, 28−35. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt021 [13] Su X, Zhao J. Connecting information to promote public health. Front Engin Manag, 2016; 3, 384−9. doi: 10.15302/J-FEM-2016054 [14] Yan WR, Nie SF, Xu B, et al. Establishing a web-based integrated surveillance system for early detection of infectious disease epidemic in rural China: a field experimental study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, 2012; 12, 4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-4 [15] Wang L, Wang Y, Jin S, et al. Emergence and control of infectious diseases in China. Lancet, 2008; 372, 1598−605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61365-3 [16] Guo Y, Su XM. Mobile device-based reporting system for Sichuan earthquake-affected areas infectious disease reporting in China. Biomed Environ Sci, 2012; 25, 724−9. [17] The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Law of the People’s Republic of China on prevention and treatment of infectious diseases (2004 revision). http://www.gov.cn/banshi/2005-05/25/content_971.htm. [2019-4-30]. (In Chinese) [18] National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. The adjustment of the management of some notifiable infectious diseases. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yjb/s3577/201304/. [2019-4-30]. (In Chinese) [19] National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on incorporating hand foot and mouth disease into the management of statutory infectious diseases. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/200805/. [2019-4-30]. (In Chinese) [20] Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, et al. Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2017; 17, 716−25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30227-X [21] National Health and Family Planning Commission.China Global AIDS Response Progress Report, 2015. http://unaids.org.cn/pics/20160614144959.pdf. [2019-4-30]. [22] UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data 2018. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf. [2019-4-30]. [23] Liu Z, Shi O, Yan Q, et al. Changing epidemiological patterns of HIV and AIDS in China in the post-SARS era identified by the nationwide surveillance system. BMC Infect Dis, 2018; 18, 700. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3551-5 [24] Cao H, Nguyen T, Daniels N. HIV/AIDS and Public Health Care in the Greater Mekong River Region. In: Lu Y., Essex M., Stiefvater E. (eds) AIDS in Asia. Springer, Boston, MA, 2004; 61-71. [25] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2009) Migrant health: Background note to the ‘ECDC Report on migration and infectious diseases in the EU’. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/publications/0907_ter_migrant_health_background_note.pdf. [2014-9-20]. [26] World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. https://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/. [2019-4-30]. [27] World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Viral hepatitis in Mongolia: situation and response 2015. https://iris.wpro.who.int/handle/10665.1/13069. [2019-4-30]. [28] National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Action plan of China malaria elimination (2010–2020). [cited 2010 May 26]. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/s5873/201005/. [2019-4-30]. (In Chinese) [29] Lai S, Li Z, Wardrop NA, et al. Malaria in China, 2011-2015: an observational study. Bull World Health Organ, 2017; 95, 564−73. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.191668 [30] National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Enhancement of management and supervision of malaria elimination. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s7929/201805/. [2019-5-10]. (In Chinese) [31] Wang Y, Wang X, Liu X, et al. Epidemiology of imported infectious diseases, China, 2005-2016. Emerg Infect Dis, 2018; 25, 33−41. doi: 10.3201/eid2501.180178 [32] Lai S, Wardrop NA, Huang Z, et al. Plasmodium falciparum malaria importation from Africa to China and its mortality: an analysis of driving factors. Sci Rep, 2016; 6, 39524. doi: 10.1038/srep39524 [33] Guzman MG, Harris E. Dengue. Lancet, 2015; 385, 453−65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60572-9 [34] Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature, 2013; 496, 504−7. doi: 10.1038/nature12060 [35] Sun J, Lu L, Wu H, et al. Epidemiological trends of dengue in mainland China, 2005-2015. Int J Infect Dis, 2017; 57, 86−91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.007 [36] Chen QQ, Meng YJ, Li Y, et al. Frequency, duration and intensity of dengue fever epidemic risk in townships in Pearl River Delta and Yunnan in China, 2013. Biomed Environ Sci, 2015; 28, 388−95. [37] Lai S, Huang Z, Zhou H, et al. The changing epidemiology of dengue in China, 1990-2014: a descriptive analysis of 25 years of nationwide surveillance data. BMC Med, 2015; 13, 100. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0336-1 [38] World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. A Guide to clinical management and public health response for hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD). [39] Van Panhuis WG, Grefenstette J, Jung SY, et al. Contagious diseases in the United States from 1888 to the present. N Engl J Med, 2013; 369, 2152−8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1215400 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links