-

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared new coronavirusdisease 2019 (COVID-2019) a pandemic, and by May 17, 2020 there were more than 4,525,497 confirmed cases[1]. With the present knowledge, the COVID-19 virus is mainly transmitted via respiratory droplets; as a result, surgical face masks are recommended to reduce coronavirus transmission from symptomatic individuals[2]. The spreading speed of SARS-CoV-2 worldwide is appalling and unfortunately, it will take at least one year or more to develop a vaccine. As a result, non-drug intervention is important, and in response, China CDC has issued a series of educational instructions to inform the public on COVID-19[3]. To evaluate the effectiveness of the instructions, a survey was conducted using the official China CDC WeChat account.

On March 18, 2020, the CDC issued an invitation to Chinese citizens aged 18 and older from any of the 31 mainland China provinces (autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the central government, excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, China) to participate in the survey. The China CDC WeChat official platform covers the 31 mainland China provinces. During the survey period, 14,174 individuals clicked the survey linkage, and 5,761 individuals completed the survey. Individuals who agreed to participate in the study were asked to complete questionnaires that were collected 24 h after the agreement to participate.

The questionnaire had three parts: general demographics, basic knowledge of COVID-19, and public mask usage in different settings. The demographic characteristics included age, occupation, education, place of residence, and respondents medical conditions. The questionnaire asked whether the participants had been infected with COVID-19 and whether there were individuals with COVID-19 nearby. Thirteen true-false questions about basic knowledge of COVID-19 were asked: seven questions about the route of transmission and six about the disease characteristics. A correct answer counted as 1 point and an incorrect answer counted as 0 points. Attitudes towards COVID-19 were assessed with 15 questions about mask usage in different settings.

The data was collected in Excel and R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.r-project.org/) was used for descriptive analyses of knowledge, behavior, and compliance. A nonparametric test was used for multiple set comparisons of independent counting data, rank-sum tests were used for comparison of ordinal data, and a chi-square test was used to analyze the classified data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 5,761 individuals completed the survey. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents, including age, occupation, and educational achievement. 263 (4.6%) respondents indicated that they have or have had COVID-19; 257 (4.5%) respondents indicated that people around them have had COVID-19.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents and knowledge scores of COVID-19

Characteristics Number (%) Knowledge score (Mean ± SD) Z P Age group (years) 157.37 < 0.001 18–29 1,624 (28.2) 10.48 ± 1.65 30–49 3,393 (58.9) 10.87 ± 1.64 50–59 634 (11.0) 11.27 ±1.47 ≥ 60 110 (1.9) 11.52 ±1.35 Occupation 303.69 < 0.001 Health system worker 1,340 (23.3) 11.42 ±1.26 Retired 170 (3.0) 11.30 ± 1.42 Student 773 (13.4) 10.35 ± 1.68 Farmer 77 (1.3) 10.03 ± 2.00 Migrant worker 240 (4.2) 10.63 ± 1.74 Worker in companies or public institutions 2,373 (41.2) 10.68 ± 1.68 Other 788 (13.7) 10.69 ± 1.70 Education 122.13 < 0.001 Middle school or below 354 (6.1) 10.06 ± 1.95 High school or technical secondary school 801 (13.9) 10.44 ± 1.72 Junior college or above 4,606 (80.0) 10.94 ± 1.57 Residency 40.40 < 0.001 Beijing 545 (9.5) 11.14 ± 1.48 Hubei 96 (1.7) 11.17 ± 1.37 Shanghai 170 (3.0) 10.90 ± 1.55 Guangdong 322 (5.6) 11.11 ± 1.41 Other 4,628 (80.3) 10.75 ± 1.67 Whether people around you had COVID-19 10.18 0.010 Yes 257 (4.5) 11.04 ± 1.43 No 5,504 (95.5) 10.80 ± 1.65 Presence of comorbid conditions 5.14 0.023 Yes 748 (13.0) 10.94 ± 1.61 No 5,013 (87.0) 10.80 ± 1.64 Table 1 shows the scores on COVID-19 knowledge. With a maximum possible score of 13, the mean score in the knowledge section was 10.82 (SD: 2.68, range: 3–13); 1,950 (33.8%) respondents answered all seven knowledge questions correctly. Knowledge scores varied significantly by age, occupation, education level, place of residence, and presence of an underlying medical condition. Older adults, health care workers, those with greater educational achievement, comorbidities, who that had reported having COVID-19, and residents of Shanghai and Guangdong had more knowledge of COVID-19 than other groups.

Most (73.3%) respondents considered COVID-19 to be serious or very serious; nearly all (99.7% and 97.2%) answered that ‘respiratory droplets’ and ‘direct contact’ were the primary modes of coronavirus transmission. Knowledge of coronavirus transmission was not related to whether a participant indicated that they had been infected. Respondents 50 years and older were more likely than younger individuals to believe that mosquito bites, dog bites, cat bites, virus contamination of intact skin, food, or water can spread COVID-19.

Table 2 shows mask usage in different situations before and during the COVID-19 epidemic, including when having respiratory symptoms, when going to the hospital, when going shopping, when taking public transportation, and when going to work. Before the COVID-19 epidemic, 49.1% of the respondents always wore a mask if they had respiratory symptoms; and of the 51.7% of respondents that had gone to a hospital, 96.6% always wore a mask. During the COVID-19 epidemic, 5,411 respondents had gone shopping, and among those, 99.4% would use a mask. Among those who took public transportation during the epidemic, 99.6% always wore a mask. Among the 79.0% of respondents who had gone back to work, 75.5% always wore a mask at work and another 24.3% sometimes wore a mask at work. Table 2 shows these behaviors nationally, and in Hubei, Beijing, and Shanghai.

Table 2. Basic knowledge of COVID-19 and mask using behavior in different living environments

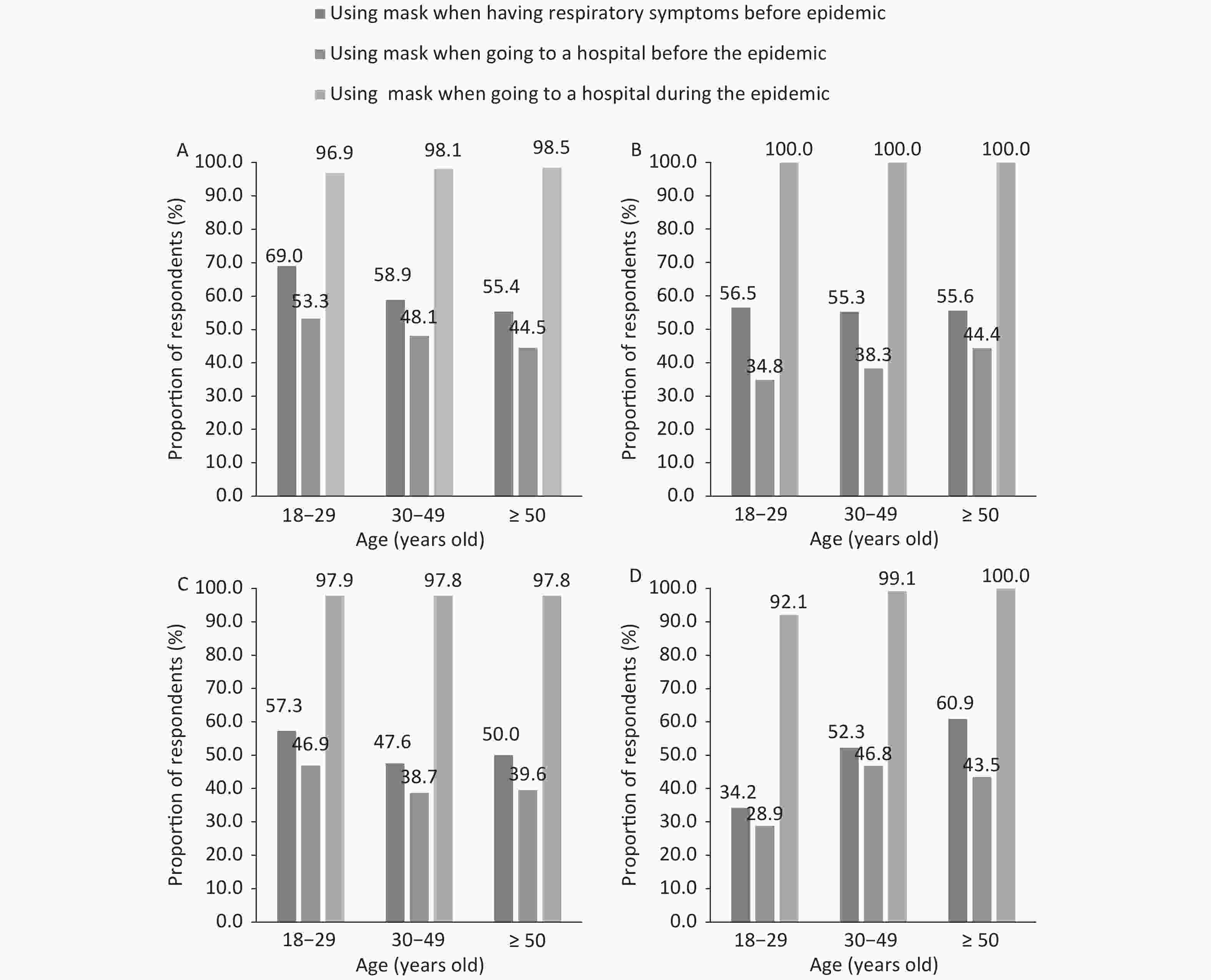

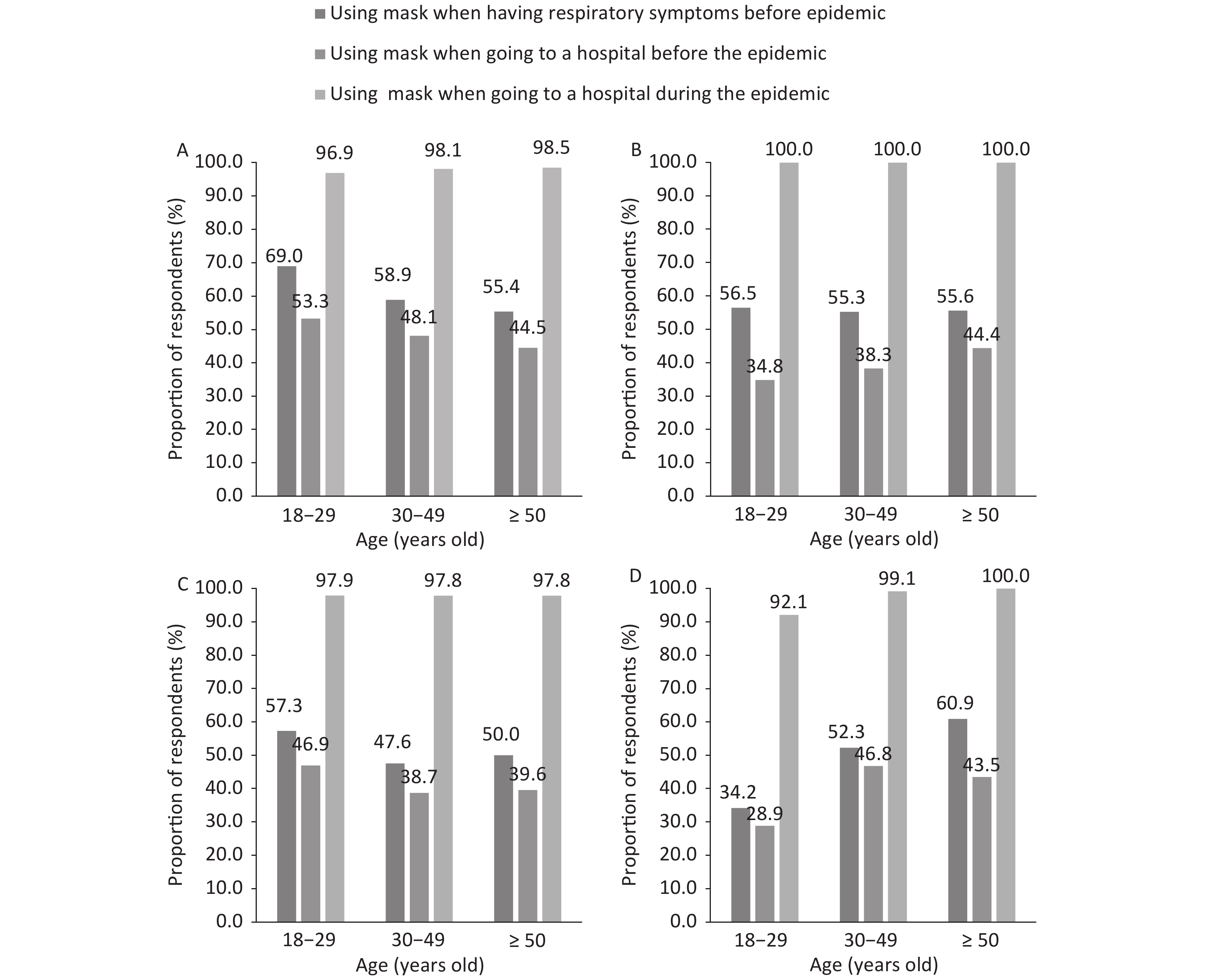

Number % answering ‘Yes’ China Hubei Beijing Shanghai Number % Number % Number % Number % Knowledge for COVID-19 Transmission route Respiratory droplets 5,742 99.7 96 100.0 543 99.6 170 100.0 Mosquito bites 991 17.2 13 13.5 57 10.5 17 10.0 Direct contact with oral, nasal, and eye mucosa 5,598 97.2 95 99.0 540 99.1 165 97.1 Dog bite, cat scratch 1,144 19.9 16 16.7 62 11.4 23 13.5 Air distance 1,406 24.4 13 13.5 91 16.7 54 31.8 Contamination of intact skin 1,681 29.2 27 28.1 135 24.8 44 25.9 Food and water 2,432 42.2 40 41.7 212 38.9 68 40.0 The main feature is of COVID-19 General susceptibility 5,154 89.5 89 92.7 499 91.6 150 88.2 More severe in older persons 5,528 96.0 93 96.9 525 96.3 168 98.8 More severe in persons with chronic diseases 5,419 94.1 96 100.0 519 95.2 165 97.1 Relatively mild in childhood 3,968 68.9 75 78.1 400 73.4 112 65.9 Most have a good prognosis and few are critical conditions 5,520 95.8 94 97.9 529 97.1 168 98.8 The severity of COVID-19 in your view Very mild 85 1.5 1 1.0 12 2.2 0 0.0 Mild 279 4.8 9 9.4 47 8.6 18 10.6 General 1,172 20.3 23 24.0 138 25.3 41 24.1 Serious 2,324 40.3 42 43.8 227 41.7 65 38.2 Critical 1,901 33.0 21 21.9 121 22.2 46 27.1 Using mask behaviors in different situations Had respiratory symptoms before the COVID-19 epidemic Never 1,157 20.1 30 31.3 112 20.6 46 27.1 Sometimes 1,074 18.6 16 16.7 161 29.5 40 23.5 Always 3,530 61.3 50 52.1 272 49.9 84 49.4 Went to the hospital before the COVID-19 epidemic Never 2,367 41.1 57 59.4 262 48.1 89 52.4 Sometimes 565 9.8 5 5.2 63 11.5 9 5.3 Always 2,829 49.1 34 35.4 220 40.4 72 42.4 Went to the hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 23 0.4 0 0.0 2 0.4 1 0.6 Sometimes 68 1.2 1 1.0 2 0.8 3 1.8 Always 2,885 50.1 45 46.9 256 47.0 110 64.7 Never been to a hospital 2,785 48.3 50 52.1 283 51.9 56 32.9 Going shopping during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 5 0.1 0 0.0 1 0.2 0 0.0 Sometimes 26 0.5 1 1.0 6 1.1 0 0.0 Always 5,380 93.4 76 79.2 508 93.2 160 94.1 Never have gone shopping 350 6.1 19 20.0 30 5.5 10 5.9 Taking public transportation during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 4 0.1 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 Sometimes 10 0.2 0 0.0 2 0.4 1 0.6 Always 3,331 57.8 37 38.5 290 53.2 132 77.7 Never have taken public transportation 2,416 41.9 59 61.5 253 46.4 37 21.8 Returning to work during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 12 0.2 0 0.0 1 0.2 0 0.0 Sometimes 1,104 19.2 11 11.5 154 28.3 39 22.9 Always 3,432 59.6 34 35.4 286 52.5 110 64.7 Work has not yet resumed 1,213 21.1 51 53.1 104 19.1 21 12.4 Using which type of mask when going to the hospital with acute respiratory symptoms during the COVID-19 epidemic Disposable face mask 1,540 26.7 28 29.2 121 22.2 67 39.4 Medical surgical mask/N95 or KN95 mask 4,149 72.0 66 68.8 414 76.0 102 60.0 Protective mask 25 0.4 1 1.0 4 0.7 1 0.6 Don’t know 47 0.8 1 1.0 6 1.1 0 0.0 Figure 1 shows the mask usage behavior by age group and residence (nationally, Hubei, Shanghai, and Beijing) in three situations – when respondents had respiratory symptoms before the COVID-19 epidemic, going to a hospital before the COVID-19 epidemic, and going to the hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. Among 18–29 year olds who visited a hospital before the epidemic, 53.3% stated that they wore a mask when visiting the hospital, compared with 96.9% who stated they wore a mask when visiting the hospital during the epidemic. Mask usage at the hospital increased by similar amounts for all age groups and in all geographic areas when compared with the mask use before and during the epidemic.

Figure 1. The proportion of people using masks in different age groups according to the area: China (A), Hubei (B), Beijing (C), and Shanghai (D)

As the seventh coronavirus that affects humans, COVID-19 is spread primarily by respiratory droplets and direct contact. Masks, especially disposable medical masks/surgical mask/N95 masks can physically prevent virus-containing respiratory droplets from reaching a healthy person. Notably, there is increasing evidence that asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 can transmit the virus[4], potentially seeding new outbreaks[5]. The infection of the COVID-19 virus is also shown by transmission to healthcare workers (HCWs): in China, more than 3,300 HCWs were infected by early March 2020, and 20% of HCWs in Italy were infected[6], emphasizing the necessity of personal protective equipment (PPE), especially masks. A previous study showed that respiratory infection occurred in 59.5% of the HCWs, regardless of whether they were in a high or low risk area of the hospital[7]. Additionally, other research has shown that using a mask can reduce the respiratory virus transmission by six fold, and can effectively reduce the spread of influenza infections[8].

In our survey, an important finding was the nearly 100% public awareness of the transmission route (‘respiratory droplets’ and ‘direct contact’) and nearly 100% public compliance for mask usage in China. For example during the COVID-19 epidemic, 96.9% of the respondents who had gone to a hospital wore masks, and 72.0% with acute respiratory symptoms (such as fever, persistent dry cough, or other symptoms) would choose a medical surgical mask/N95 or KN95 mask when going to the hospital. However, before the epidemic, 58.9% chose to use a mask when going to the hospital (the proportion is potentially greater than actual). Data from 2009 showed only 1.3% chose to wear a mask outside of the home to prevent influenza transmission[9]. It is likely this lower value is near the usage before the COVID-19 epidemic. Compared with 96.9% of respondents currently using a mask to go to the hospital, the public compliance for using a mask in China has increased dramatically. During the COVID-19 epidemic, a London underground driver tested positive for the coronavirus[10], which indicates a public driver is a high-risk occupation. Thus, high mask use compliance (99.6%) in China, particularly while taking public transportation could benefit protection of these high-risk occupations and personnel. Public awareness of COVID-19 can be improved by television, WeChat, newspapers, Internet social platforms, as well as friends and family. Behavior of the public is influenced by educational background, government enforcement, views of others, perceptions of severity, social promotion, and education. For example, a report revealed 43.7% indicated the biggest obstacle to mask use was how others looked at them when using a mask[9]. The combination of requirements and public education has largely been successful at promoting the use of masks as a simple intervention to reduce coronavirus transmission and infection. However, mask usage is not recognized as effective by all countries: only 37.8% of the US public and 29.7% of the UK public believe that using a common surgical mask is ‘highly effective’ in protecting people from COVID-19 infection[11]. In response to prevention of influence in China in 2009, 27.9% would use a mask in crowded places, and 70.8% would never use a mask[9]. The results of the present study illustrate that mask usage is now deeply rooted in Chinese public behavior. Furthermore, more than 70.0% considered COVID-19 to be ‘serious’ or ‘very serious’. While 61.0% of the US and 71.7% UK respondents thought that the number of fatalities from COVID-19 in their country will be ≤ 500 people by the end of 2020[11]. Correct public knowledge and anxiety are contributing to near-universal public awareness of transmission routes and public mask usage of COVID-19.

Elderly people, who are vulnerable to COVID-19, had good mask usage compliance after the outbreak of COVID-19. In general, the understanding of COVID-19 among older individuals was more accurate than the understanding among younger people. During the COVID-19 epidemic, people in the 50–59 year old age group stated that they wore masks more often when going to the hospital than respondents in the 18–29 age group. People younger than 49 years old were more likely to believe that the coronavirus can be transmitted by food and water; the belief that virus contamination of intact skin, long distances, through dog, cat, and mosquito bites can occur was significantly greater among respondents 50 years and older. Although we did not determine the basis of the respondents’ beliefs, it may by that older people have more trust in official education and have more family responsibilities, while younger people have more information sources that form their judgement. Additionally, people with comorbidities knew more about COVID-19 than people without. Perhaps comorbidities are more common among older people, partially confounding the age-related findings. However, our data shows that people with comorbidities, before the COVID-19 epidemic, 5.9% who had gone to a hospital used masks. There was no statistical significance compared with people without comorbid conditions (7.3%). The COVID-19 epidemic attracts more attention of people with comorbidities, engaging the use of masks when going to the hospital than people without comorbidities (98.4% vs. 97.8%).

Finally, mask usage is influenced by local fashion and culture. In Asia, the use of masks increased during the SARS epidemic and post-SARS. For example, during the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic, 88.75% of people wore face masks when they had an influenza-like illness (ILI) and 21.5% wore face masks regularly in public in Hong Kong, China[12]. In our data, before the COVID-19 outbreak, respondents aged 18–29 who had ‘influenza-like illness’ were significantly more likely to use masks than other age groups, indicating a potential fashion and cultural influence.

Online surveys provide a rapid method to track public knowledge and behavior. However, our study has several limitations that should be considered. First, although the data we collected came from 31 provinces and cities in China, our respondents were not a random sample; therefore, their representation of the province was limited. Second, medical workers were over-represented, and medical workers have more knowledge of COVID-19 than other occupational groups. The reason for over-representativeness may be because medical staff more commonly use the ‘China CDC’ official account. Third, the smartphone application did not allow for returning and changing answers; as a result, the value of 58.9% (3,394/5,761) choosing to use a mask when going to the hospital before the epidemic was greater than the actual percentage. Fourth, our research is insufficient enough to identify the percentage of people who may have knowledge but take no action.

The pace of the COVID-19 epidemic is alarming. Bommer and Vollmer estimated that the 40 most affected countries had only identified an average of approximately 9% of the coronavirus infections by March 30, 2020[13]. More recent data shows that surgical masks prevent the spread of human coronavirus and influenza virus by symptomatic people, and the coronavirus is present in 4/10 of exhaled air samples from individuals without masks, compared with 0/11 among individuals using masks[2]. Of course, whether masks are effective and whether supplies of masks are insufficient are two different problems, but insufficiency of supply is a problem that can be addressed[14]. After the COVID-19 outbreak, masks were recommended for suspected infected patients and their nursing staff in most countries, and then masks were recommended to cover mouth and nose[15]. According to George F Gao, a Chinese scientist, ‘the big mistake in the U.S. and Europe, in my opinion, is that people aren’t using masks’[16]. Some people may think that using masks is excessive. In balancing the expense of excessive protection with the large economic losses caused by the pandemic, using a mask is a possibly efficient and economic choice. As of April 30, 2020, the Chinese capital—Beijing reduced its emergency response to the epidemic to the second level. We look forward to additional research and attention regarding mask usage nationally and globally to help prevent the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus.

doi: 10.3967/bes2020.085

Public Awareness and Mask Usage during the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Survey by China CDC New Media

-

Abstract: An online survey conducted March 18–19, 2020 on the official China CDC WeChat account platform was used to evaluate the effect of public education about masks usage during the new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. Chinese nationals older than 18 were eligible for the survey. The survey collected 5,761 questionnaires from the 31 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions of mainland China. 99.7% and 97.2% of the respondents answered correctly that respiratory droplets and direct contact were the main transmission routes. 73.3% of the respondents considered COVID-19 to be ‘serious’ or ‘very serious’. When going to the hospital, 96.9% (2,885/2,976 had gone to a hospital) used a mask during the COVID-19 epidemic, while 41.1% (2,367/5,761) did not use a mask before the epidemic. Among the respondents that used public transportation and went shopping, 99.6% and 99.4%, respectively, wore masks. Among respondents who returned to work, 75.5% wore a mask at the workplace, while 86.3% of those who have not returned to work will choose to use masks when they return to the workplace. The Chinese public is highly likely to use a mask during COVID-19 epidemic, and the mask usage changed greatly since the COVID-19 outbreak. Therefore, public education has played an important role during the COVID-19 epidemic .

-

Key words:

- COVID-19 /

- Mask /

- Public awareness /

- Public behaviors /

- Social media platform

注释: -

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents and knowledge scores of COVID-19

Characteristics Number (%) Knowledge score (Mean ± SD) Z P Age group (years) 157.37 < 0.001 18–29 1,624 (28.2) 10.48 ± 1.65 30–49 3,393 (58.9) 10.87 ± 1.64 50–59 634 (11.0) 11.27 ±1.47 ≥ 60 110 (1.9) 11.52 ±1.35 Occupation 303.69 < 0.001 Health system worker 1,340 (23.3) 11.42 ±1.26 Retired 170 (3.0) 11.30 ± 1.42 Student 773 (13.4) 10.35 ± 1.68 Farmer 77 (1.3) 10.03 ± 2.00 Migrant worker 240 (4.2) 10.63 ± 1.74 Worker in companies or public institutions 2,373 (41.2) 10.68 ± 1.68 Other 788 (13.7) 10.69 ± 1.70 Education 122.13 < 0.001 Middle school or below 354 (6.1) 10.06 ± 1.95 High school or technical secondary school 801 (13.9) 10.44 ± 1.72 Junior college or above 4,606 (80.0) 10.94 ± 1.57 Residency 40.40 < 0.001 Beijing 545 (9.5) 11.14 ± 1.48 Hubei 96 (1.7) 11.17 ± 1.37 Shanghai 170 (3.0) 10.90 ± 1.55 Guangdong 322 (5.6) 11.11 ± 1.41 Other 4,628 (80.3) 10.75 ± 1.67 Whether people around you had COVID-19 10.18 0.010 Yes 257 (4.5) 11.04 ± 1.43 No 5,504 (95.5) 10.80 ± 1.65 Presence of comorbid conditions 5.14 0.023 Yes 748 (13.0) 10.94 ± 1.61 No 5,013 (87.0) 10.80 ± 1.64 Table 2. Basic knowledge of COVID-19 and mask using behavior in different living environments

Number % answering ‘Yes’ China Hubei Beijing Shanghai Number % Number % Number % Number % Knowledge for COVID-19 Transmission route Respiratory droplets 5,742 99.7 96 100.0 543 99.6 170 100.0 Mosquito bites 991 17.2 13 13.5 57 10.5 17 10.0 Direct contact with oral, nasal, and eye mucosa 5,598 97.2 95 99.0 540 99.1 165 97.1 Dog bite, cat scratch 1,144 19.9 16 16.7 62 11.4 23 13.5 Air distance 1,406 24.4 13 13.5 91 16.7 54 31.8 Contamination of intact skin 1,681 29.2 27 28.1 135 24.8 44 25.9 Food and water 2,432 42.2 40 41.7 212 38.9 68 40.0 The main feature is of COVID-19 General susceptibility 5,154 89.5 89 92.7 499 91.6 150 88.2 More severe in older persons 5,528 96.0 93 96.9 525 96.3 168 98.8 More severe in persons with chronic diseases 5,419 94.1 96 100.0 519 95.2 165 97.1 Relatively mild in childhood 3,968 68.9 75 78.1 400 73.4 112 65.9 Most have a good prognosis and few are critical conditions 5,520 95.8 94 97.9 529 97.1 168 98.8 The severity of COVID-19 in your view Very mild 85 1.5 1 1.0 12 2.2 0 0.0 Mild 279 4.8 9 9.4 47 8.6 18 10.6 General 1,172 20.3 23 24.0 138 25.3 41 24.1 Serious 2,324 40.3 42 43.8 227 41.7 65 38.2 Critical 1,901 33.0 21 21.9 121 22.2 46 27.1 Using mask behaviors in different situations Had respiratory symptoms before the COVID-19 epidemic Never 1,157 20.1 30 31.3 112 20.6 46 27.1 Sometimes 1,074 18.6 16 16.7 161 29.5 40 23.5 Always 3,530 61.3 50 52.1 272 49.9 84 49.4 Went to the hospital before the COVID-19 epidemic Never 2,367 41.1 57 59.4 262 48.1 89 52.4 Sometimes 565 9.8 5 5.2 63 11.5 9 5.3 Always 2,829 49.1 34 35.4 220 40.4 72 42.4 Went to the hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 23 0.4 0 0.0 2 0.4 1 0.6 Sometimes 68 1.2 1 1.0 2 0.8 3 1.8 Always 2,885 50.1 45 46.9 256 47.0 110 64.7 Never been to a hospital 2,785 48.3 50 52.1 283 51.9 56 32.9 Going shopping during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 5 0.1 0 0.0 1 0.2 0 0.0 Sometimes 26 0.5 1 1.0 6 1.1 0 0.0 Always 5,380 93.4 76 79.2 508 93.2 160 94.1 Never have gone shopping 350 6.1 19 20.0 30 5.5 10 5.9 Taking public transportation during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 4 0.1 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 Sometimes 10 0.2 0 0.0 2 0.4 1 0.6 Always 3,331 57.8 37 38.5 290 53.2 132 77.7 Never have taken public transportation 2,416 41.9 59 61.5 253 46.4 37 21.8 Returning to work during the COVID-19 epidemic Never 12 0.2 0 0.0 1 0.2 0 0.0 Sometimes 1,104 19.2 11 11.5 154 28.3 39 22.9 Always 3,432 59.6 34 35.4 286 52.5 110 64.7 Work has not yet resumed 1,213 21.1 51 53.1 104 19.1 21 12.4 Using which type of mask when going to the hospital with acute respiratory symptoms during the COVID-19 epidemic Disposable face mask 1,540 26.7 28 29.2 121 22.2 67 39.4 Medical surgical mask/N95 or KN95 mask 4,149 72.0 66 68.8 414 76.0 102 60.0 Protective mask 25 0.4 1 1.0 4 0.7 1 0.6 Don’t know 47 0.8 1 1.0 6 1.1 0 0.0 -

[1] WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation report–118. WHO. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200517-covid-19-sitrep-118.pdf?sfvrsn=21c0dafe_6 [2020-05-18] [2] Leung NHL, Chu DKW, Shiu EYC, et al. Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks. Nat Med, 2020; 26, 676−80. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0843-2 [3] China CDC. Tips of China CDC: use of masks. China CDC (WeChat subscription). 2020. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA3MzU2MzIwMg==&mid=2650690150&idx=1&sn=0dfed2845be3d91ba1d856189ef50d20&chksm=8707df4bb070565dfbfb7b39b36660118dd60d285cc5ee78a2c1ed9b106129a65f02d837d4a9&mpshare=1&scene=1&srcid=0730FeJwaPgv6jgkqJdt3Joi&sharer_sharetime=1596100477062&sharer_shareid=4c4555d56f8fc23d072adb729e95636f&key=f8fcfe1a6c069eef2c7e7c373506a0bbf6fad33871db8e4aa952b293fe78d16c986c030ca2e846305870c6e0ebba2f36ce8208ecea5f5d12d25d3ba6c21d0dece273a6ffbe2431e540bafacb6c212cb6&ascene=1&uin=MjE3NzA4NTY0MQ%3D%3D&devicetype=Windows+10+x64&version=62090529&lang=zh_CN&exportkey=AcnDXX%2F1ass91Y5%2FGLhvaTA%3D&pass_ticket=u1mH7s1dgFJUyg3JOaEPEdOBbPLfQYjyz8A7doKWbKrEoHt81cVWQ9UGgLa9BzGf [2020-05-05] [4] Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA, 2020; 323, 1406−7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565 [5] Jane Q. Covert coronavirus infections could be seeding new outbreaks. Nature News. 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00822-x [2020-03-05] [6] The Lancet. COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet, 2020; 395, 922. [7] Yang P, Seale H, MacIntyre CR, et al. Mask-wearing and respiratory infection in healthcare workers in Beijing, China. Braz J Infect Dis, 2011; 15, 102−8. doi: 10.1016/S1413-8670(11)70153-2 [8] Aiello AE, Murray GF, Perez V, et al. Mask use, hand hygiene, and seasonal influenza like illness among young adults: a randomized intervention trial. J Infect Dis, 2010; 201, 491−8. doi: 10.1086/650396 [9] Lifetimes. The investigation found that seven adults did not wear masks to prevent influenza. Lifetimes. 2009. http://news.sina.com.cn/h/2009-05-26/104717892130.shtml[2020-03-01] [10] Xinhua. Confirmed COVID-19 cases in UK jump to 798. Xinhua. 2020. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-03/14/c_138875576.htm [2020-03-21] (In Chinese) [11] Geldsetzer P. Use of rapid online surveys to assess people's perceptions during infectious disease outbreaks: a cross-sectional survey on COVID-19. J Med Internet Res, 2020; 22, e18790. doi: 10.2196/18790 [12] Lau JT, Griffiths S, Choi KC, et al. Prevalence of preventive behaviors and associated factors during early phase of the H1N1 influenza epidemic. Am J Infect Control, 2010; 38, 374−80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.03.002 [13] Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. Average detection rate of SARS-CoV-2 infections is estimated around nine percent. 2020. Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. https://www.uni-goettingen.de/de/606540.html [2020-04-08] [14] Feng S, Shen C, Xia N, et al. Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med, 2020; 8, 434−36. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30134-X [15] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to protect yourself &others. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html [2020-03-25] [16] Jon C. Not wearing masks to protect against coronavirus is a ‘big mistake, top Chinese scientist says. Science News. 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/not-wearing-masks-protect-against-coronavirus-big-mistake-top-chinese-scientist-says# [2020-05-05] -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links