-

Lung cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed cancers and is a major threat to human health around the world. Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) therapy has revolutionized the treatment of multiple cancers and provide hope to patients afflicted with incurable malignancies, including lung cancer[1]. ICIs primarily block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), restoring the body’s anti-tumor immune response[2]. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) are distinct toxicities that occur during ICIs treatment[1]. However, the underlying mechanisms is still unclear. Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), is a highly infectious globally disease[3]. In patients with active TB, the level of PD-1 protein was found to be higher on various immune cells compared to healthy individuals[4]. When TB was successfully treated, the level of PD-1 decreased[5]. Our previous meta-analysis demonstrated that using PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical practice significantly raises the risk of TB reactivation[6]. In this study, we aimed to examine the treatment effectiveness and safety of ICIs in lung cancer patients with or without a history of pulmonary TB and to investigate the factors associated with their efficacy and safety.

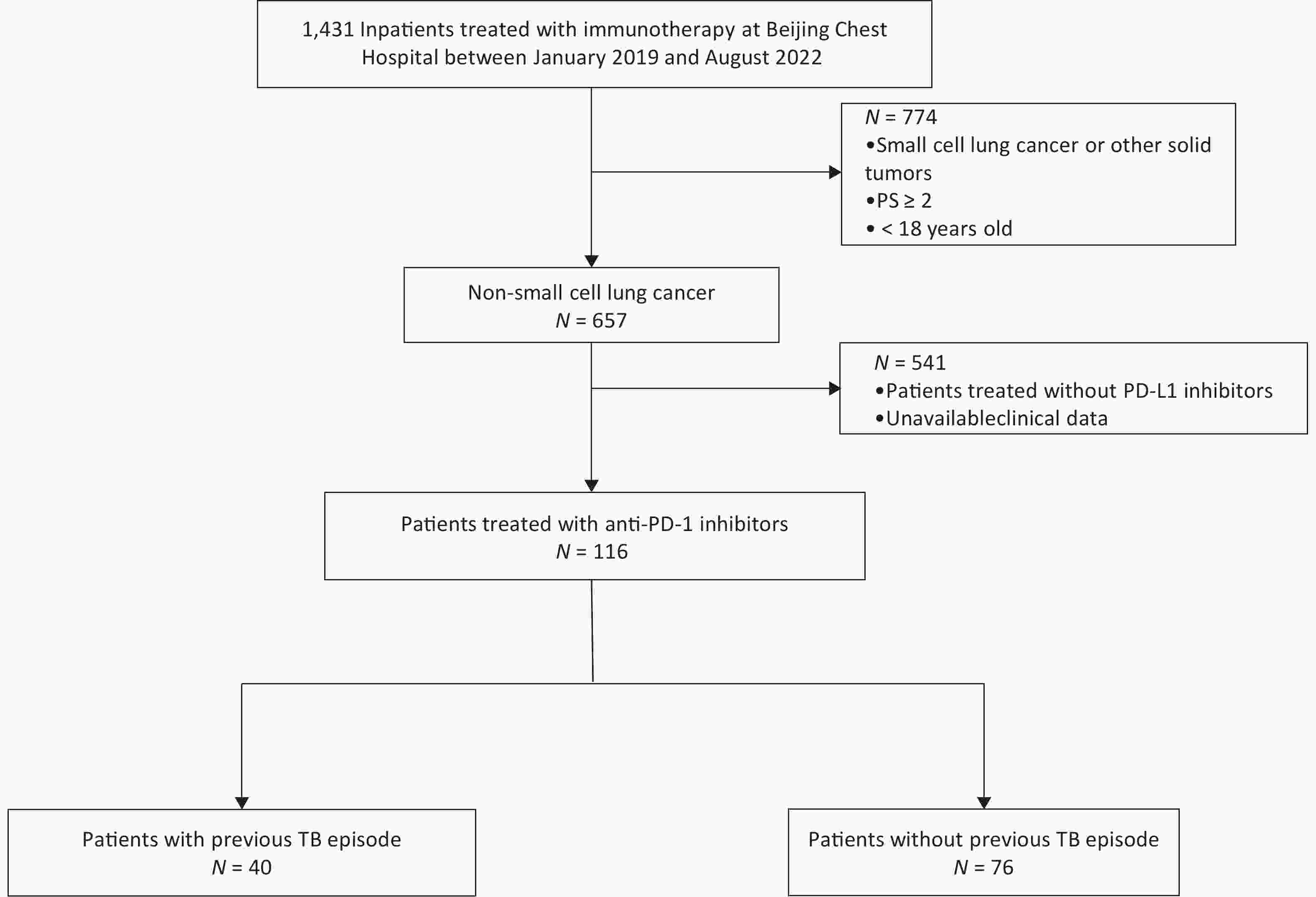

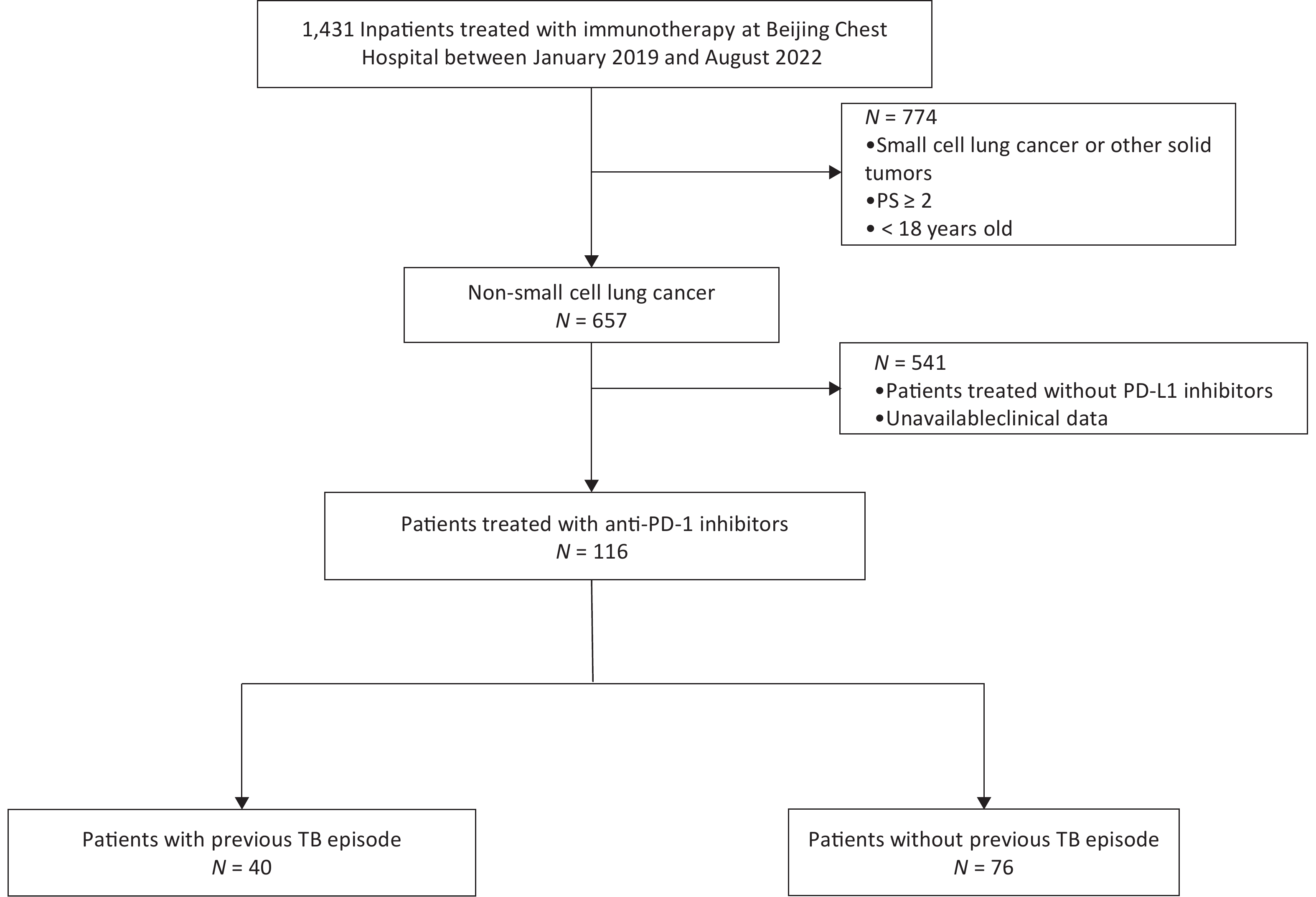

Between 2019 and 2022, we included lung cancer patients who were hospitalized in Beijing Chest Hospital. Inclusion Criteria were as follows: 1) age over 18 years old; 2) patients with cytology or histological diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); 3) no contraindications to chemotherapy and immunotherapy; 4) clinically received at least one cycle of PD-1 inhibitor treatment; 5) consent to clinical data collection. We screened a total of 116 cases that met the criteria. Among them, 40 patients had a previous episode of pulmonary TB, 7 patients did not receive anti-tuberculosis therapy, 19 patients received immunotherapy for more than 5 years at the end of anti-tuberculosis treatment, and 14 patients received immunotherapy for less than 5 years. The pulmonary TB patients were performed according to the Diagnosis for Pulmonary Tuberculosis (WS288-2017) Guidelines.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients included sex, age, smoking history, pathology type, treatment type, treatment line of ICIs, PD-L1 expression, the period between anti-TB treatment and ICIs comorbidities, efficacy evaluation and adverse events (AEs). Response assessment was performed according to the immune Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (iRECIST 1.1) after the administration of the first dose of ICIs by the investigator. The definition of AEs was based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE 5.0). The study followed procedures in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chest Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University (approved No. LW-2022-009).

All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The continuous variables were expressed as mean (SD) or median (range), and categorical variables as count (%). The continuous variables were expressed as count (%), which were assessed employing the chi-square test. In addition, the difference was declared significant if two-sided P values are less than 0.05. The figures were developed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.

116 patients treated with anti-PD-1 inhibitors met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in our study (Figure 1), of which 34.5% (40/116) had a pulmonary TB history, and 66.5% (76/116) patients didn’t. Among the 99 individuals who have the immunohistochemistry expression results of PD-L1, 58.6% of cases (68/99) were positively expressed and 31.3% of cases (31/99) were not expressed. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients were shown in (Supplementary Table S1, available in www.besjournal.com).

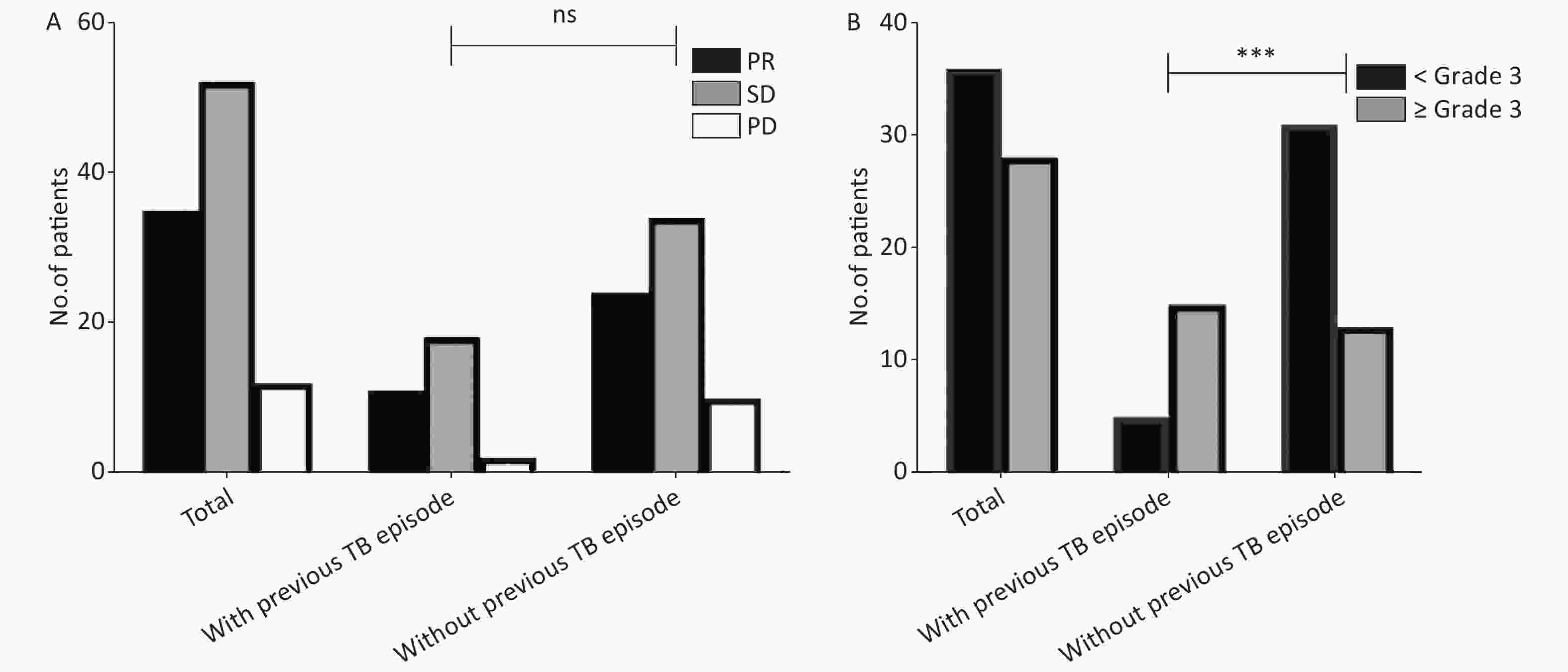

We preliminarily analyzed the influence of pulmonary TB history on the effectiveness of ICIs treatment. Of the 116 patients included, 99 had an evaluable response, of which 31 had a history of pulmonary TB and 68 did not. The result showed no statistically significant difference in objective response rate (ORR) (35.5% vs. 35.3%) and disease control rate (DCR) (93.5% vs. 85.3%) between groups with and without a history of TB (Supplementary Table S2, available in www.besjournal.com), suggesting that a history of TB does not affect the efficacy of immunotherapy (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Increased severe AEs in previous TB patients treated with immunotherapy. (A) Previous TB episodes did not affect the efficacy of immunotherapy. We analyzed the efficacy evaluation of 99 patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. (B) Increased severe AEs in previous TB patients treated with immunotherapy. We analysis the AEs of 116 patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. The grade definition of AEs was based on CTCAE 5.0. PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; TB, tuberculosis; AEs, adverse events; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1.

Table S2. Clinical efficacy of ICI therapy in lung cancer patients with or without previous tuberculosis episode

Response Number of cases evaluated (n = 99) With previous TB episode (n = 31) Without previous TB episode (n = 68) CR/PR 35 11 24 SD 52 18 34 PD 12 2 10 ORR 35.4% (35/99) 35.5% (11/31) 35.3% (24/68) DCR 87.9% (87/99) 93.5% (29/31) 85.3% (58/68) Note. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TB, tuberculosis; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; n, number. Our study suggested that patients with previous TB episodes were more likely to experience severe treatment-associated AEs. Among the 116 patients, 64 patients had adverse reactions of varying degrees (55.2%, 64/116), and among them 28 patients had grade 3 or above adverse reactions (24.1%, 28/116). The incidence of AEs showed no difference between patients with or without pulmonary TB (50.0% vs. 57.8%), but the incidence of grade 3 severe AEs was higher in patients with TB history (Figure 2B). Notably, despite a significant increase in incidence of severe adverse events among patients with previous TB episodes, this incidence in patients with latent TB infection was comparable to that in TB-naïve patients in our cohort (data not shown). A previous murine study demonstrated that PD-1 inhibition is required to prevent CD4+ T cells from facilitating development of TB[7]. Patients with active TB were associated with elevated PD-1 expression on CD4+ T cells, indicating that the delicate regulation of PD-1 level on immune cells is essential to prevent the development of active TB cases. The immunosuppression status due to upregulation of PD-1 in patients with previous TB episodes may partly explain the high incidence of autoimmune-like AEs.

In addition, we found an association between elderly individuals and increased severe AEs incidence. We summarized the characteristics of the 40 patients and analyzed the risk factors for severe AEs of lung cancer patients with previous TB episode after ICIs therapy. The result showed that only elder persons (≥ 65) exhibited a higher odds ratio (OR = 4.250, 1.087–16.614) (Supplementary Table S3 available in www.besjournal.com). We suggest two possible reasons for this phenomenon. First, elderly patients are vulnerable to AEs compared to younger patients due to the underlying comorbidities[8]. Second, the existing evidence has demonstrated the age-related decline in the immune system in preclinical studies. Interesting, aging was associated with increased expression of PD-1 on T cells[9]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the high-level expression of PD-1 increases sensitivity to cancer immunotherapy, thus leading to overactivation of immune cells and high incidence of severe adverse events.

Table S3. Risk factors for AEs of lung cancer patients with previous TB episode after ICI therapy

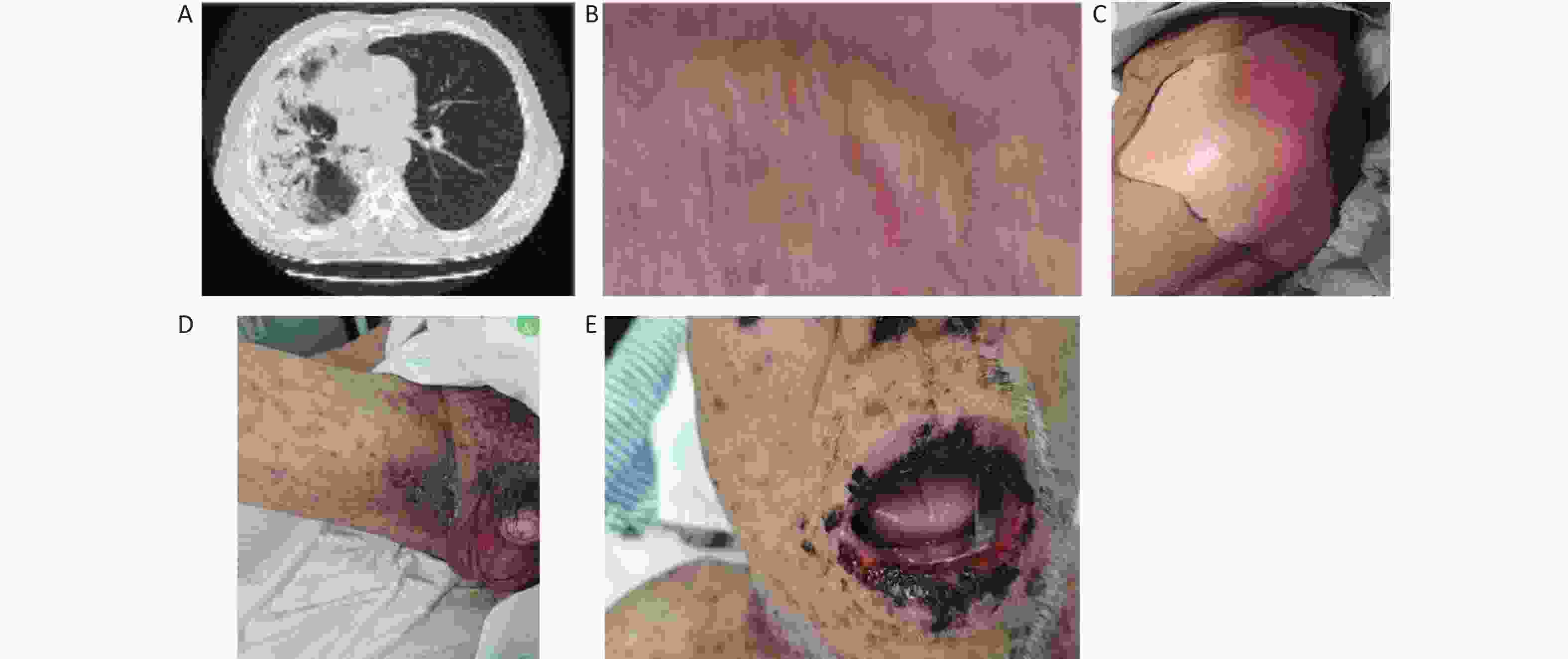

Parameters Patients without severe AE (n = 25, %) Patients with severe AE (n = 15, %) Odds ratio P value Sex Male 23 (91.2) 14 (93.3) 0.821 (0.068–0.914) > 0.999 Female 2 (8.0) 1 (6.7) Age, years ≥ 65 8 (32.0) 10 (66.7) 4.250 (1.087–16.614) 0.033 < 65 17 (68.0) 5 (33.3) Smoking Yes 21 (84.0) 12 (80.0) 1.313 (0.250–6.879) > 0.999 No 4 (16.0) 3 (20.0) Pathology Squamous 14 (56.0) 7 (46.7) 1.455 (0.402–5.260) 0.567 Adenocarcinoma 11 (44.0) 8 (53.3) Treatment ICI+chemotherapy 20 (80.0) 13 (86.7) 0.615 (0.104–3.658) 0.691 ICI 5 (20.0) 2 (13.3) Line of treatment First 17 (68.0) 11 (73.3) 0.773 (0.187–3.196) > 0.999 Second or later 8 (32.0) 4 (26.7) PD-L1 expression Negative 8 (40.0) 5 (41.7) 0.933 (0.218–3.999) > 0.999 Positive 12 (60.0) 7 (58.3) Period between anti-TB treatment and ICI ≥ 5 years 12 (48.0) 7 (46.7) 1.055 (0.293–3.803) > 0.999 < 5 years 13 (52.0) 8 (53.3) Note. AE, adverse events; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TB, tuberculosis; n, number. Among the 40 NSCLC patients with pulmonary TB who received PD-L1 inhibitors, 15 patients developed ≥ Grade 3 AEs during treatment. Also, the time to onset of AEs of these 15 patients is varying, ranging from one cycle to six cycles of treatment. Several organs were involved in the adverse event reactions, including lung, bone marrow, liver, gallbladder, skin, thyroid, heart and muscle. Three patients developed recurrent tuberculosis after receiving PD-1 inhibitors and had to stop antitumor therapy and receive antituberculosis therapy (Supplementary Table S4, available in www.besjournal.com). Here, we reported two cases. One is a 71-year-old male lung adenocarcinoma patient after regular anti-TB treatment and received 4 cycles of ICIs (Figure 3A–C). The other is a 66-year-old male lung squamous cell carcinoma patient with stable TB and received 1 cycle of ICI (Figure 3D–E). The concurrent involvement of multiple sites at presentation suggests a potential role for overactivation immunity in the emergence of severe AEs. Several reports have indicated the presence of dysfunctional state of T cells in chronic MTB infection via upregulating the expression of inhibitory receptors such as PD-1[10]. As a consequence, PD-1 blockade can reverse the state of effector T cells, thus causing high levels of proinflammatory cytokines that are associated with extensive tissue damage.

Figure 3. The characteristics of 2 patients with severe AEs. A–C: 71-year-old male lung adenocarcinoma patient after regular anti-TB treatment who received 4 cycles of ICI plus chemotherapy treatment. (A) Grade 3 immune-related pneumonitis; (B) Grade 4 bullous rash; (C) Grade 4 Epidermal necrolysis (CTCAE version 5.0). (D–E) 66-year-old male lung squamous cell carcinoma patient with stable TB who received 1 cycle of ICI plus chemotherapy treatment and occur grade 4 rashes (CTCAE version 5.0). TB, tuberculosis; AEs, adverse events; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

Table S4. Severe adverse events of lung cancer patients with previous TB episode

ID Cycles of treatment Organs involved No. of organs Reoccurrence of TB Pneumonitis Marrow Intestinal gastric organs Kidney Fever Liver and gallbladder Skin Thyroid Heart Muscle Ureter 1 3 ● 1 2 1 ● ● ● ● ● 5 3 1 ● ● 2 4 4 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 5 1 ● 1 6 2 ● 1 7 6 ● 1 8 5 ● ● 2 9 5 ● 1 10 6 ● ● 2 11 1 ● ● ● 3 12 4 ● 1 13 1 ● ● ● ● 4 14 4 ● ● 2 15 1 ● ● ● ● 4 Recent studies have suggested that the clinical use of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are associated with an increasing incidence of active TB patients in cancer patients with latent tuberculosis infection6. In our patient cohort, three patients experienced TB relapse during the PD-1inhibtor therapy. Based on our data, we expect that the patients with previous TB episodes were at higher risk for development of active TB disease than latent TB following anti-PD-1 treatment. Considering that PD-1 blockade becomes more deployed in TB endemic regions, TB screening before immunotherapy is warranted to identify individuals at high risk for development of active TB cases.

Our study is subject to some limitations. For example, the retrospective design, including patients with different treatment backgrounds, could be riddled with several confounding factors. Furthermore, the sample size is limited. We are willing to include more cases in the future. Additionally, the potential interpretations for the finding that previous TB episodes were more likely to experience severe treatment-associated AEs was lack of experimental evidence.

In conclusion, our data firstly demonstrate that patients with previous TB episodes are more likely to experience severe treatment-associated AEs. We also identify an association between elderly individuals and increased severe AEs incidence. In addition, the patients with previous TB episodes are at higher risk for development of active TB disease than latent TB following anti-PD-1 treatment. Our results emphasize that TB screening before immunotherapy is warranted.

-

Not applicable.

-

The study followed procedures in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chest Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University (approved No. LW-2022-009).

-

All the authors agree to publish this article in European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

-

Table S1. Demographic and clinical characteritics of patients enrolled in the final cohort

Parameters Number of patients Percentage (%) Sex Male 92 70.3 Female 24 20.7 Age, years ≥ 65 58 50.0 < 65 58 50.0 Smoking Yes 105 90.5 No 11 9.5 Pathology Squamous 55 47.4 Adenocarcinoma 57 49.1 Others 4 3.4 Therapy ICI+chemotherapy 104 89.7 ICI 12 10.3 Regimen type First-line 95 81.9 Second-line 21 18.1 PD-L1 expression Negative 31 26.7 Positive 68 58.6 Past history of TB Yes 40 34.5 No 76 65.5 Note. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TB, tuberculosis.

doi: 10.3967/bes2024.119

Increased Incidence of Severe Adverse Events in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients with Previous Tuberculosis Episode Treated with PD-1 Inhibitors

-

Abstract: Lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths globally. Advances in immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have transformed cancer treatment, but their use in lung cancer has led to more side effects. This study examined if past pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) affects ICIs’ effectiveness and safety in lung cancer treatment. We reviewed lung cancer patients treated with ICIs at Beijing Chest Hospital from January 2019 to August 2022. We compared outcomes and side effects between patients with and without prior TB. Of 116 patients (40 with TB history, 76 without), prior TB didn't reduce treatment effectiveness but did increase severe side effects. Notably, older patients (≥ 65 years) faced a higher risk of severe side effects. Detailed cases of two patients with severe side effects underscored TB as a risk factor in lung cancer patients receiving ICIs, stressing the need for careful monitoring and personalized care.

-

Key words:

- Lung cancer /

- Tuberculosis /

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors /

- Adverse events /

- PD-1

None declared.

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) Author Contributions: 2) Conflict of Interest: -

Figure 2. Increased severe AEs in previous TB patients treated with immunotherapy. (A) Previous TB episodes did not affect the efficacy of immunotherapy. We analyzed the efficacy evaluation of 99 patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. (B) Increased severe AEs in previous TB patients treated with immunotherapy. We analysis the AEs of 116 patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. The grade definition of AEs was based on CTCAE 5.0. PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; TB, tuberculosis; AEs, adverse events; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1.

Figure 3. The characteristics of 2 patients with severe AEs. A–C: 71-year-old male lung adenocarcinoma patient after regular anti-TB treatment who received 4 cycles of ICI plus chemotherapy treatment. (A) Grade 3 immune-related pneumonitis; (B) Grade 4 bullous rash; (C) Grade 4 Epidermal necrolysis (CTCAE version 5.0). (D–E) 66-year-old male lung squamous cell carcinoma patient with stable TB who received 1 cycle of ICI plus chemotherapy treatment and occur grade 4 rashes (CTCAE version 5.0). TB, tuberculosis; AEs, adverse events; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

S2. Clinical efficacy of ICI therapy in lung cancer patients with or without previous tuberculosis episode

Response Number of cases evaluated (n = 99) With previous TB episode (n = 31) Without previous TB episode (n = 68) CR/PR 35 11 24 SD 52 18 34 PD 12 2 10 ORR 35.4% (35/99) 35.5% (11/31) 35.3% (24/68) DCR 87.9% (87/99) 93.5% (29/31) 85.3% (58/68) Note. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TB, tuberculosis; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; n, number. S3. Risk factors for AEs of lung cancer patients with previous TB episode after ICI therapy

Parameters Patients without severe AE (n = 25, %) Patients with severe AE (n = 15, %) Odds ratio P value Sex Male 23 (91.2) 14 (93.3) 0.821 (0.068–0.914) > 0.999 Female 2 (8.0) 1 (6.7) Age, years ≥ 65 8 (32.0) 10 (66.7) 4.250 (1.087–16.614) 0.033 < 65 17 (68.0) 5 (33.3) Smoking Yes 21 (84.0) 12 (80.0) 1.313 (0.250–6.879) > 0.999 No 4 (16.0) 3 (20.0) Pathology Squamous 14 (56.0) 7 (46.7) 1.455 (0.402–5.260) 0.567 Adenocarcinoma 11 (44.0) 8 (53.3) Treatment ICI+chemotherapy 20 (80.0) 13 (86.7) 0.615 (0.104–3.658) 0.691 ICI 5 (20.0) 2 (13.3) Line of treatment First 17 (68.0) 11 (73.3) 0.773 (0.187–3.196) > 0.999 Second or later 8 (32.0) 4 (26.7) PD-L1 expression Negative 8 (40.0) 5 (41.7) 0.933 (0.218–3.999) > 0.999 Positive 12 (60.0) 7 (58.3) Period between anti-TB treatment and ICI ≥ 5 years 12 (48.0) 7 (46.7) 1.055 (0.293–3.803) > 0.999 < 5 years 13 (52.0) 8 (53.3) Note. AE, adverse events; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TB, tuberculosis; n, number. S4. Severe adverse events of lung cancer patients with previous TB episode

ID Cycles of treatment Organs involved No. of organs Reoccurrence of TB Pneumonitis Marrow Intestinal gastric organs Kidney Fever Liver and gallbladder Skin Thyroid Heart Muscle Ureter 1 3 ● 1 2 1 ● ● ● ● ● 5 3 1 ● ● 2 4 4 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 5 1 ● 1 6 2 ● 1 7 6 ● 1 8 5 ● ● 2 9 5 ● 1 10 6 ● ● 2 11 1 ● ● ● 3 12 4 ● 1 13 1 ● ● ● ● 4 14 4 ● ● 2 15 1 ● ● ● ● 4 S1. Demographic and clinical characteritics of patients enrolled in the final cohort

Parameters Number of patients Percentage (%) Sex Male 92 70.3 Female 24 20.7 Age, years ≥ 65 58 50.0 < 65 58 50.0 Smoking Yes 105 90.5 No 11 9.5 Pathology Squamous 55 47.4 Adenocarcinoma 57 49.1 Others 4 3.4 Therapy ICI+chemotherapy 104 89.7 ICI 12 10.3 Regimen type First-line 95 81.9 Second-line 21 18.1 PD-L1 expression Negative 31 26.7 Positive 68 58.6 Past history of TB Yes 40 34.5 No 76 65.5 Note. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; TB, tuberculosis. -

[1] Tang H, Zhou JF, Bai CM. The efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer and preexisting autoimmune disease. Front Oncol, 2021; 11, 625872. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.625872 [2] Shiravand Y, Khodadadi F, Kashani SMA, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr Oncol, 2022; 29, 3044−60. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29050247 [3] Zumla A, Raviglione M, Hafner R, et al. Tuberculosis. N Engl J Med, 2013; 368, 745−55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1200894 [4] Shen L, Gao Y, Liu YY, et al. PD-1/PD-L pathway inhibits M. tb-specific CD4+ T-cell functions and phagocytosis of macrophages in active tuberculosis. Sci Rep, 2016; 6, 38362. doi: 10.1038/srep38362 [5] Hassan SS, Akram M, King EC, et al. PD-1, PD-L1 and PD-L2 gene expression on T-cells and natural killer cells declines in conjunction with a reduction in PD-1 protein during the intensive phase of tuberculosis treatment. PLoS One, 2015; 10, e0137646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137646 [6] Liu KW, Wang DP, Yao C, et al. Increased tuberculosis incidence due to immunotherapy based on PD-1 and PD-L1 blockade: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol, 2022; 13, 727220. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.727220 [7] Barber DL, Mayer-Barber KD, Feng CG, et al. CD4 T cells promote rather than control tuberculosis in the absence of PD-1-mediated inhibition. J Immunol, 2011; 186, 1598−607. [8] Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, et al. International society of geriatric oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2014; 32, 2595−603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347 [9] Henson SM, Macaulay R, Riddell NE, et al. Blockade of PD-1 or p38 MAP kinase signaling enhances senescent human CD8+ T-cell proliferation by distinct pathways. Eur J Immunol, 2015; 45, 1441−51. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445312 [10] Khan N, Vidyarthi A, Amir M, et al. T-cell exhaustion in tuberculosis: pitfalls and prospects. Crit Rev Microbiol, 2017; 43, 133−41. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2016.1185603 -

24018+Supplementary Materials.pdf

24018+Supplementary Materials.pdf

-

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links