-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which ranks among the most common chronic liver conditions worldwide, affects approximately 30% of the global population[1]. In 2020, this disease was renamed as metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) to emphasize its association with metabolic dysregulation[2]. More recently, the term "metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MASLD)" was proposed to further characterize its association with broader metabolic health profiles[3]. Throughout this study, we adopted the MAFLD nomenclature, which is consistent with the original research context, while acknowledging the emerging MASLD terminology. Despite extensive research, the pathogenesis of MAFLD (previously NAFLD) remains incompletely elucidated, highlighting the need for deeper mechanistic insights.

Nevertheless, compelling evidence has demonstrated the significant role of gut microbiota in metabolism-related diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and fatty liver disease[4,5]. Given that the liver predominantly derives its blood supply from the portal vein, it is uniquely susceptible to gut-derived factors. Specifically, the gut microbiota and the byproducts resulting from the fermentation of food by these microbes can readily reach and impact the liver. This complex and dynamic interaction between the gut and the liver is an essential part of what is termed the “gut-liver axis”[6]. The portal venous blood functions as a conduit by ferrying dietary components or commensal organisms (along with their metabolites) to the liver. Concurrently, bile secreted by the liver travels through the bile duct into the intestine and is subsequently reabsorbed into the portal blood, thus creating a continuous and reciprocating cycle that characterizes the gut-liver axis[7]. Consequently, disturbances of the gut microbiota taxa and their metabolites may instigate a series of hepatic pathologies via the bloodstream[8].

Several cohort studies have shown that patients with MAFLD exhibited unique microbial alterations in the composition and function of their gut microbiota[9-11]. Compared with healthy individuals, patients with MAFLD exhibited a significant decrease in the alpha diversity of the gut microbiota and marked changes in its composition. For example, there was a remarkable increase in the abundance of Proteobacteria and Dorea, while Ruminococcaceae decreased[4]. However, current evidence is only associative; thus, Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis is essential, as it can determine causal ties[12].

To conduct an effective MR analysis, accurate and detailed characterization of the gut microbiota is required. Initially, 16S rRNA profiling was widely used to detect gut microbiota, analyzing its composition and quantity at or above the genus level. However, 16S rRNA gene sequencing has limited resolution and often fails to distinguish between species[13]. As next-generation sequencing (NGS) has been rapidly developed, shotgun metagenomic sequencing has overcome these limitations and driven gut microbiota research from genus-level analysis to species-level identification[13]. Currently, the MR analysis of gut microbiota and MAFLD mainly uses Genome-wide Association Study (GWAS) summary data from the MiBioGen Consortium (www.mibiogen.org)[14], which employs 16S rRNA for fecal microbiome sequencing. The heterogeneity of MR analysis often leads to inconsistent results and challenges in establishing robust causal inferences[15-21].

Therefore, in this study, we instead used shotgun metagenomic sequencing data from two extensive GWAS studies on gut microbiota taxa[22,23], and conducted de novo bidirectional Univariate Mendelian randomization (UVMR) analyses between gut microbiota taxa and MAFLD. In clinical settings, imaging techniques are essential for the non-invasive diagnosis and evaluation of MAFLD[24]. Ultrasonography is the most commonly used diagnostic tool for MAFLD in large-scale studies due to its accessibility, safety, and low cost[24].In our study, the MAFLD phenotype was defined based on hepatic steatosis diagnosed via ultrasonography[25], ensuring compatibility with real-world clinical diagnoses and broad population coverage. To preclude any potential discrepancies, we conducted an in-depth review of all existing MR studies on gut microbiota and NAFLD/MAFLD. We performed a meta-analysis to substantiate and corroborate these results. Multivariable and mediation analyses were conducted to identify potential mediating metabolites. Through these approaches, we aimed to enhance our understanding of the gut microbiota-MAFLD interplay and pave the way for potential mechanistic studies of metabolic mediators.

-

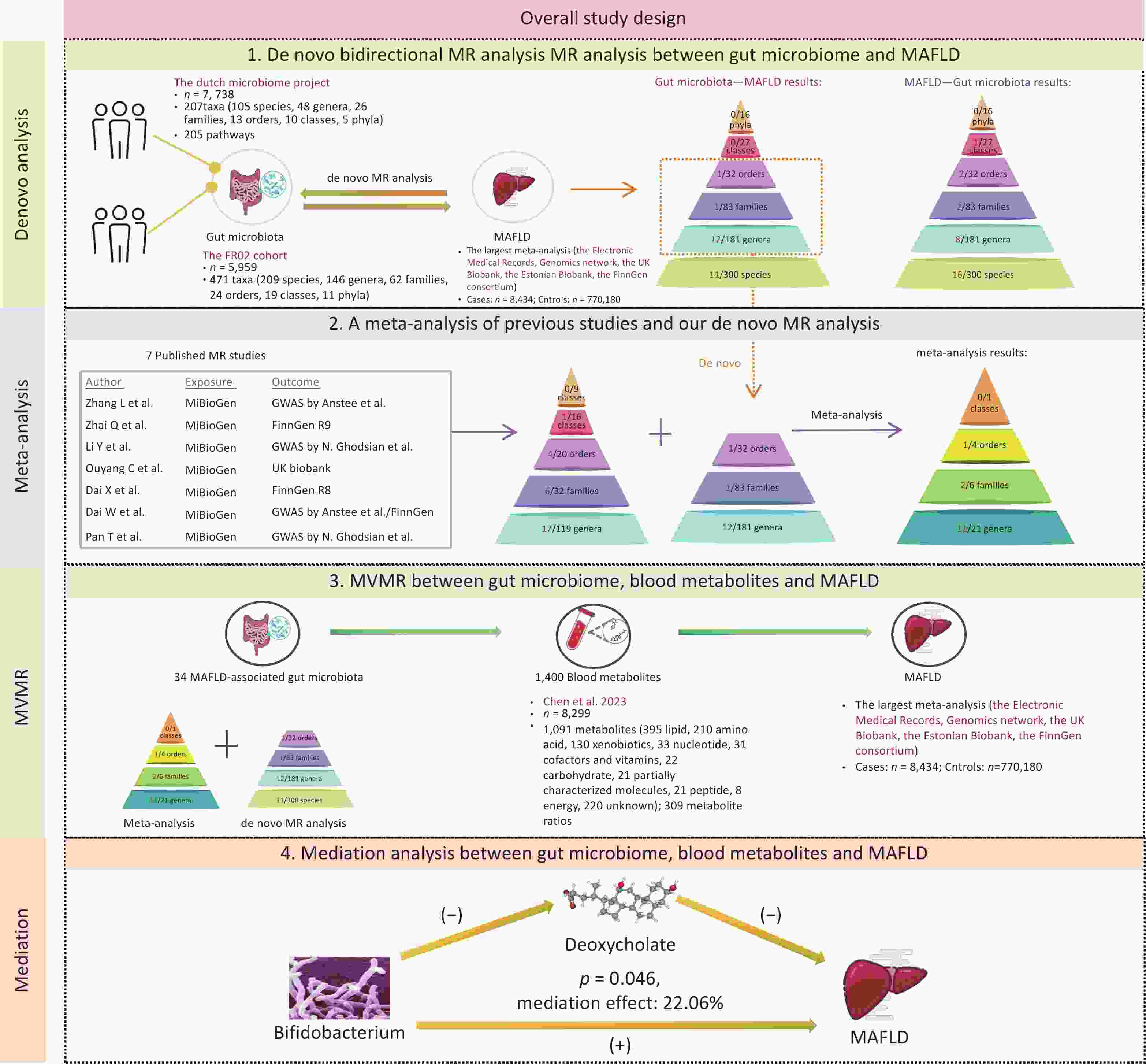

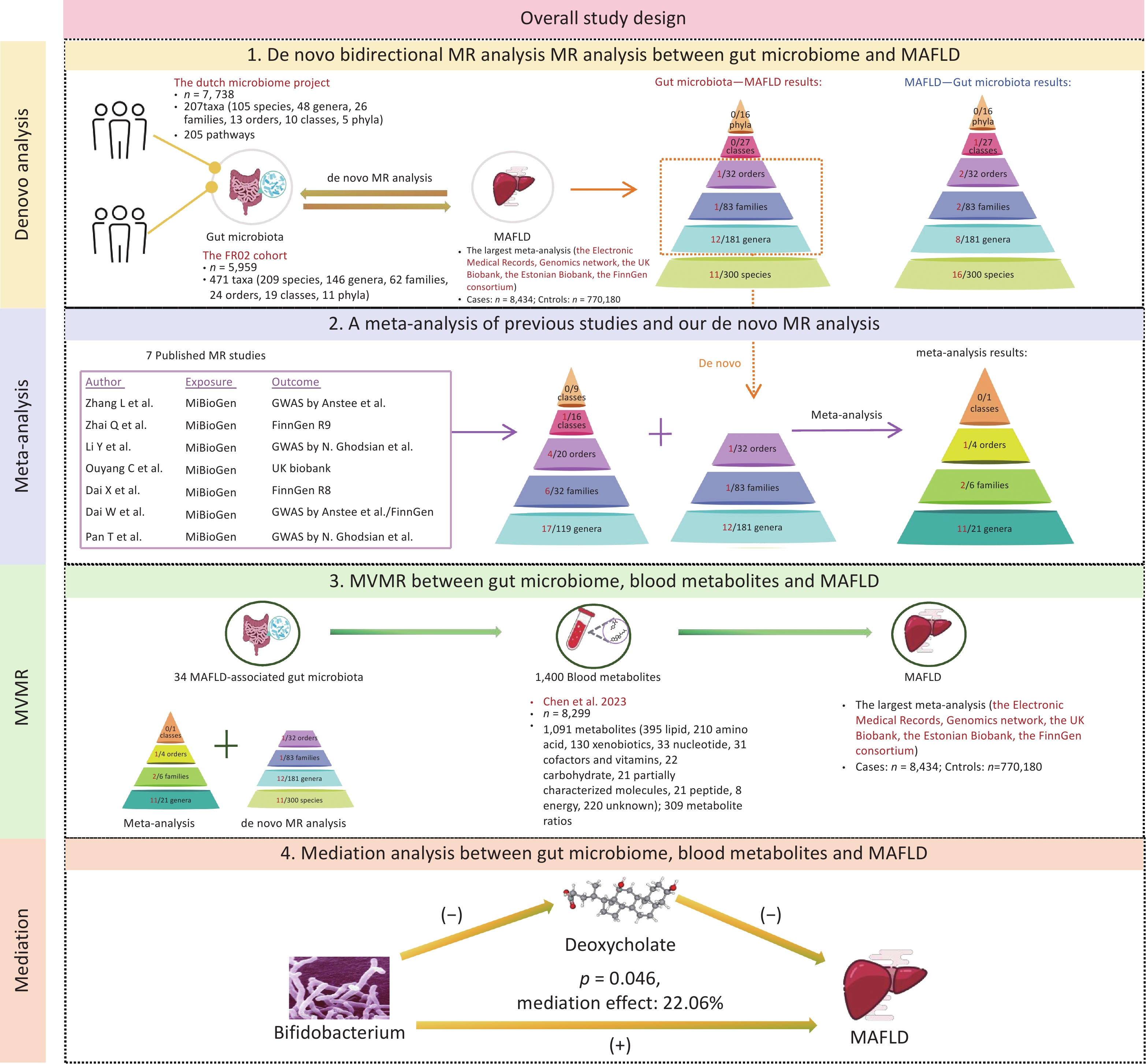

The methodological framework of this study is shown in Figure 1. The MR study was designed according to the STROBE-MR checklist (Supplementary Table S1). The research design was systematically refined into four pivotal stages. First, we performed de novo UVMR analyses to explore potential associations between the gut microbiome (412 gut microbiome by Lopera-Maya EA et al.[22] and 471 gut microbiome by Qin Y et al.[23]) and MAFLD. Second, we searched for published MR studies concerning the gut microbiome and NAFLD/MAFLD, and integrated these with our de novo analyses using a meta-analytic approach. Third, we focused on blood metabolites as candidate mediators in the association between the gut microbiome and MAFLD using Multivariable Mendelian Randomization (MVMR), to explore potential mediating effects. Finally, we conducted a mediation analysis to more clearly illustrate the potential mediating effects.

-

The GWAS summary statistics for the gut microbiota were derived from two distinct sources. The first dataset was derived from the Dutch Microbiome Project, encompassing 205 bacterial pathways and 207 taxa (5 phyla, 10 classes, 13 orders, 26 families, 48 genera, and 105 species) from 7,738 participants[22]. The second dataset originated from the FR02 cohort, which comprises 471 taxa (11 phyla, 19 classes, 24 orders, 62 families, 146 genera, and 209 species) from 5,959 individuals[23].

The summary data on MAFLD were extracted from the largest meta-analysis, encompassing four European ancestry cohorts: the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics network, the UK Biobank, the Estonian Biobank, and the FinnGen consortium. This comprehensive analysis covered 8,434 MAFLD cases and 770,180 controls[25].

For the blood metabolites, we leveraged the GWAS summary statistics from a pivotal investigation that quantified 1,091 distinct metabolites and 309 metabolite ratios across a cohort of 8,299 participants[26].

-

We conducted a de novo bidirectional UVMR analysis to estimate the total effect of the gut microbiome on MAFLD. We selected single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IVs) for the gut microbiota, using a threshold of 1 × 10-5. We excluded SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD; R2 < 0.001) within a 10,000 kilobase pairs window. For SNPs not directly available from the GWAS results, suitable proxy SNPs were selected. The inverse–variance weighted (IVW) method was adopted as the primary approach for estimating causal effects, MR Egger, weighted median, simple mode, and weighted mode were utilized as supplementary methods[27].

-

A comprehensive literature review was performed on the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane library database, using the following MeSH terms and keywords: “Gastrointestinal Microbiome” [MeSH], “Gut Microbiome”, “Gut Microflora”, “Gut Flora”, “Intestinal Microbiome”, “Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease” [MeSH], “Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease”, and “Mendelian Randomization Analysis” [MeSH]. Eligible studies published up to December 1, 2024, were then methodically screened and identified for subsequent analyses. When two or more MR estimates were available for the same exposure based on non-overlapping samples, a combined estimate was obtained via meta-analysis. Two independent reviewers conducted the literature screening, and any discrepancies in the process were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer. The study was performed according to PRISMA and STROBE-MR guidelines.

We collected data, including the first author's name, year of publication, information on exposure and outcomes, such as the consortium, study population ancestry, total number of participants (both cases and controls), number of SNPs, F-statistics, odds ratio (OR), along with a 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the inverse-variance weighted method, and the P-value of causal estimates.

-

We conducted UVMR analysis of 1,400 blood metabolites related to MAFLD and then concentrated on metabolites causally linked to the disease for further mediation analysis. In the UVMR analysis of these metabolites, IVs were set with a 1 × 10-5 threshold, and SNPs in LD (R2 < 0.001) within a 10,000 kb window were excluded. The IVW method was employed to estimate causal effects. The selection methodology is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. To consider the potential genetic confounders, MVMR analysis was performed to calculate the direct effects of the gut microbiome on MAFLD[28].

-

Subsequently, a mediation analysis was performed using a two-step MR approach to identify mediation metabolites. First, we determined the direct effects of the gut microbiota on MAFLD through MVMR, taking into account the role of metabolites. Next, we calculated the indirect effects, denoted as “mediated effect,” by multiplying β1 by β2. Here, β1 represented the causal effect of gut microbial taxonomy on the blood metabolite, and β2 represented that of the mediator on MAFLD. The significance of the mediating effects (β1×β2) and its proportion in the total effect were estimated by the delta method.

-

Cochran’s Q statistic and MR-Egger regression test were used to quantify the heterogeneity of the selected SNPs in the MR analysis. The P-values exceeding 0.05 indicate the absence of heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy. Additionally, leave-one-out analysis was performed to evaluate the individual influence of a single SNP on the outcome. The heterogeneity of the meta-analysis was estimated by calculating the I2 statistic (25%–50%: mild heterogeneity; 50%–75%: moderate heterogeneity; > 75%: severe heterogeneity). Publication bias was scrutinized through funnel plot analysis.

In R software (version 4.2.2), the following packages were used for statistical calculations: "TwoSampleMR" (version 0.5.7) for MR analyses, "meta" (version 7.0.0) and "metafor" (version 4.6.0) for meta-analyses, and "MRInstruments" (version 0.3.2) for handling MR instruments.

-

In the forward de novo MR analysis, a total of 678 taxa and 205 bacterial pathways were assessed for their association with MAFLD. The detailed SNPs associated with the gut microbiome (taxa and bacterial pathways) and MAFLD are shown in Supplementary Tables S2–S4, respectively.

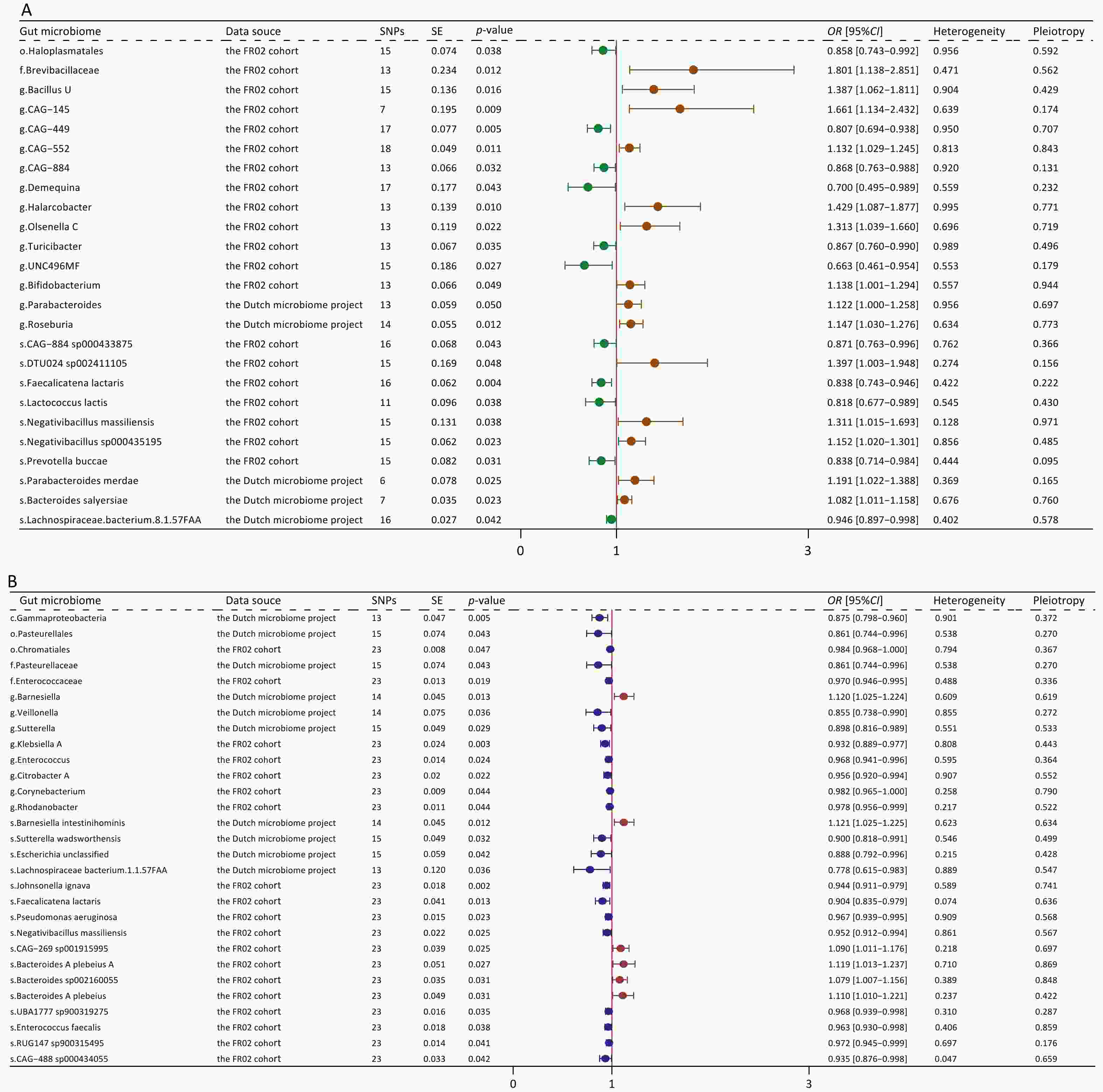

Using the IVW method, we identified 25 microbial taxa with significant correlations (P < 0.05). Moreover, 14 of these taxa were associated with an increased risk of MAFLD (Figure 2A). Gut microbime at the species level included DTU024 sp002411105 (OR [95% CI] = 1.397 [1.003–1.948], P = 0.048), Negativibacillus massiliensis (OR [95% CI] = 1.311 [1.015–1.693], P = 0.038), Negativibacillus sp000435195 (OR [95% CI] = 1.152 [1.02–1.301], P = 0.023), Parabacteroides merdae (OR [95% CI] = 1.191 [1.022-1.388], P = 0.025), and Bacteroides salyersiae (OR [95% CI] = 1.082 [1.011–1.158], P = 0.023).

Figure 2. Forest plot of bidirectional causal effects between gut microbial taxa and MAFLD (P < 0.05). (A) Causal effects of gut microbial taxa on MAFLD; (B) Causal effects of MAFLD on gut microbial taxa. SNPs, number of SNPs; SE, standard error of coefficient estimate; P-value, the P-value of causal estimation in the IVW method; OR [95% CI], odds ratio and 95% confidence interval; Heterogeneity, the P-value of heterogeneity analysis; Pleiotropy, the P-value of horizontal pleiotropy analysis.

Conversely, 11 taxa were associated with a decreased risk of MAFLD. Gut microbime at the species level included Lachnospiraceae bacterium (8_1_57FAA) (OR [95% CI] = 0.946 [0.897–0.998], P = 0.002), CAG-884 sp000433875 (OR [95% CI] = 0.871[0.763–0.996], P = 0.043), Faecalicatena lactaris (OR [95% CI] = 0.838 [0.743–0.946], P = 0.004), Lactococcus lactis (OR [95% CI] = 0.818 [0.677–0.989], P = 0.038), and Prevotellabuccae (OR [95% CI] = 0.838 [0.714–0.984], P = 0.031). The results obtained using additional MR methods, including MR-Egger, weighted median, weighted mode, and simple mode, also supported these findings (Supplementary Table S5). Sensitivity analyses revealed no significant heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy.

In the reverse MR analysis, we identified 29 significant causal associations (Figure 2B). Specifically, MAFLD exhibited positive correlations with 6 taxa, whereas it presented negative correlations with additional 23 taxa (Supplementary Figure S2; Supplementary Table S6). Upon comparing these results with those derived from the forward MR analysis, we found no taxa overlap. Our analysis also found 10 specific pathways that were causally associated with MAFLD, including 6 protective pathways and 4 risk pathways (Supplementary Figure S3A). In the reverse MR analysis, MAFLD was causally associated with 7 pathways (Supplementary Figure S3B).

-

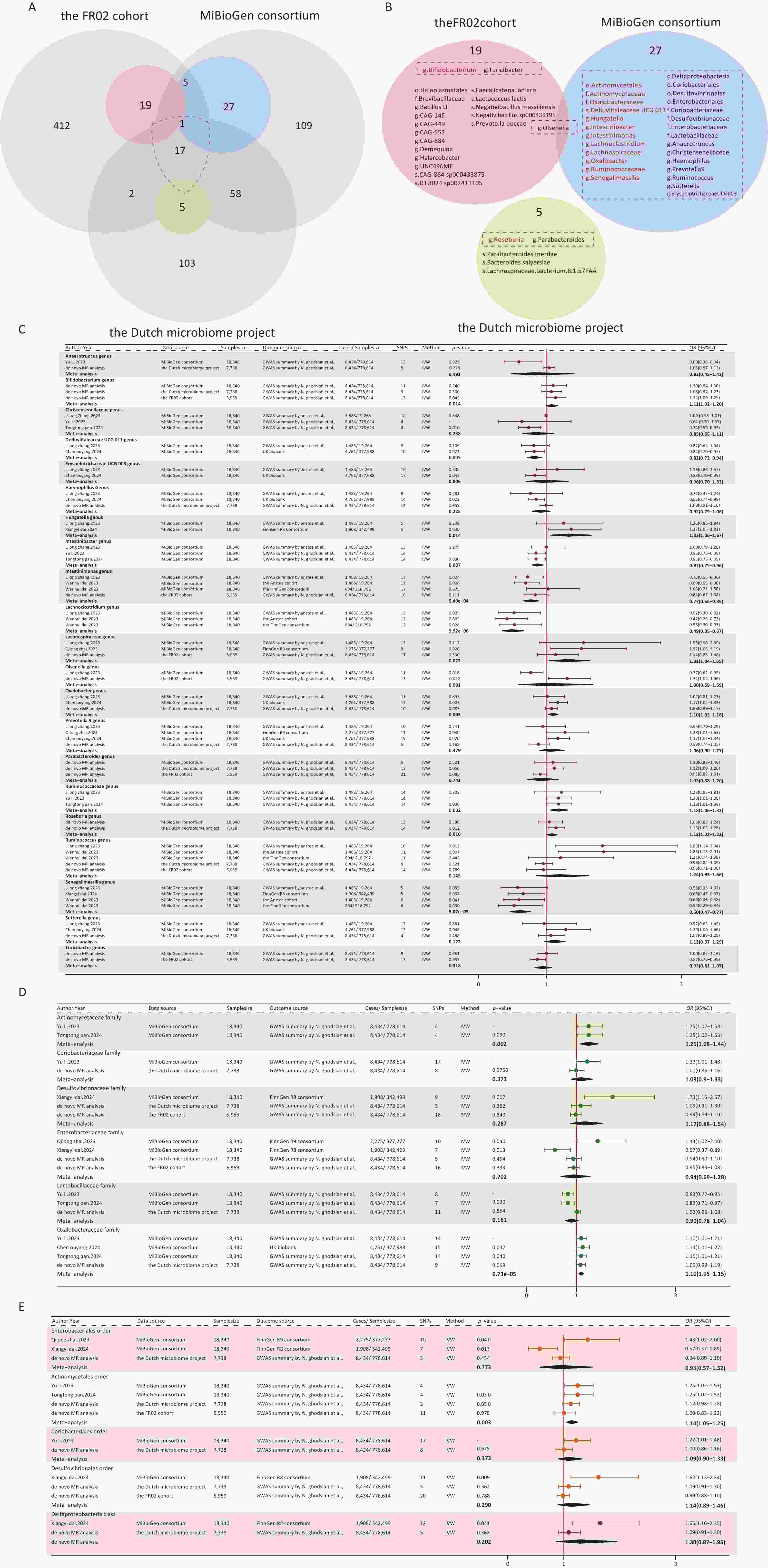

After a comprehensive literature review, 7 MR articles exploring the link between the gut microbiome and NAFLD/MAFLD were identified and included in this study[15-21]. Notably, all of these studies utilized gut microbiome data from the MiBioGen consortium, which encompassed 211 bacterial taxa (9 phyla, 16 classes, 20 orders, 35 families, and 131 genera) from 18,340 individuals[14]. Upon comparing this consortium with the dataset used in our de novo analysis, we identified 18 shared taxa (2 classes, 2 orders, 5 families, and 9 genera) (Figure 3A). Detailed information on the selected publications is presented in Supplementary Table S7.

Figure 3. Forest plot of the meta-analysis of gut microbial taxa and MAFLD. (A) Intersection of three gut microbiome datasets. Grey circles: taxa not significantly associated with MAFLD. Blue, pink, green circles: taxa significantly associated with MAFLD. (B) Overall meta-analysis results, the gut microbiota in the dashed boxes were included in the meta-analysis. Red: consistently statistically associated with MAFLD after meta-analysis. Black: not significantly associated after meta-analysis. (C) Meta-analysis forest plot at the genus level. (D) Meta-analysis forest plot at the family level. (E) Meta-analysis forest plot at the order and class level. Source, gut microbial taxa; SNPs, number of SNPs; P-value, the P-value of causal estimation in the IVW method; OR [95% CI], odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

We summarized the positive results reported in the literature, as well as those from our de novo analysis, and ultimately included a total of 32 bacterial taxa that met the conditions for meta-analysis (Figure 3B). Eventually, 14 taxa (1 order, 2 families, and 11 genera) were found to be associated with MAFLD (Figure 3C–E). Moreover, 20 taxa from our de novo analysis were not included in the meta-analysis because there was no overlap between studies. Among the 14 taxa identified by the meta-analysis, 9 taxa were genetically associated with an increased risk for MAFLD, including the order Actinomycetales (OR [95% CI] = 1.14 [1.05–1.25], P = 0.003), the family Actinomycetaceae (OR [95% CI] = 1.25 [1.08–1.44], P = 0.002), Oxalobacteraceae (OR [95% CI] = 1.10 [1.05–1.15], P = 6.73ⅹ10-5), and the genus Hungatella (OR [95% CI] = 1.33 [1.06–1.67], P = 0.014), Bifidobacterium (OR [95% CI] = 1.11 [1.02–1.20], P = 0.014), Lachnospiraceae (OR [95% CI] = 1.31 [1.04–1.65], P = 0.022), Oxalobacter (OR [95% CI] = 1.10 [1.03–1.18], P = 0.005), Ruminococcaceae (OR [95% CI] = 1.18 [1.06–1.32], P = 0.002), and Roseburia (OR [95% CI] = 1.02 [1.12–1.22], P = 0.016). Conversely, five taxa were found to be genetically associated with a reduced risk for MAFLD, which included the genus Defluviitaleaceae UCG011 (OR [95% CI] = 0.82 [0.72–0.94], P = 0.005), Intestinibacter (OR [95% CI] = 0.87 [0.79–0.96], P = 0.007), Intestinimonas (OR [95% CI] = 0.79 [0.69−0.91], P = 6.75ⅹ10-4), Senegalimassilia (OR [95% CI] = 0.60 [0.47–0.77], P = 5.07ⅹ10-5), and Lachnoclostridium (OR [95% CI] = 0.49 [0.35−0.6], P = 9.92ⅹ10-6). The results of the MAFLD-related taxa combined with the meta-analysis and de novo analysis are presented in Supplementary Table S8. The plots of the sensitivity analyses are shown in Supplementary Figure S4.

-

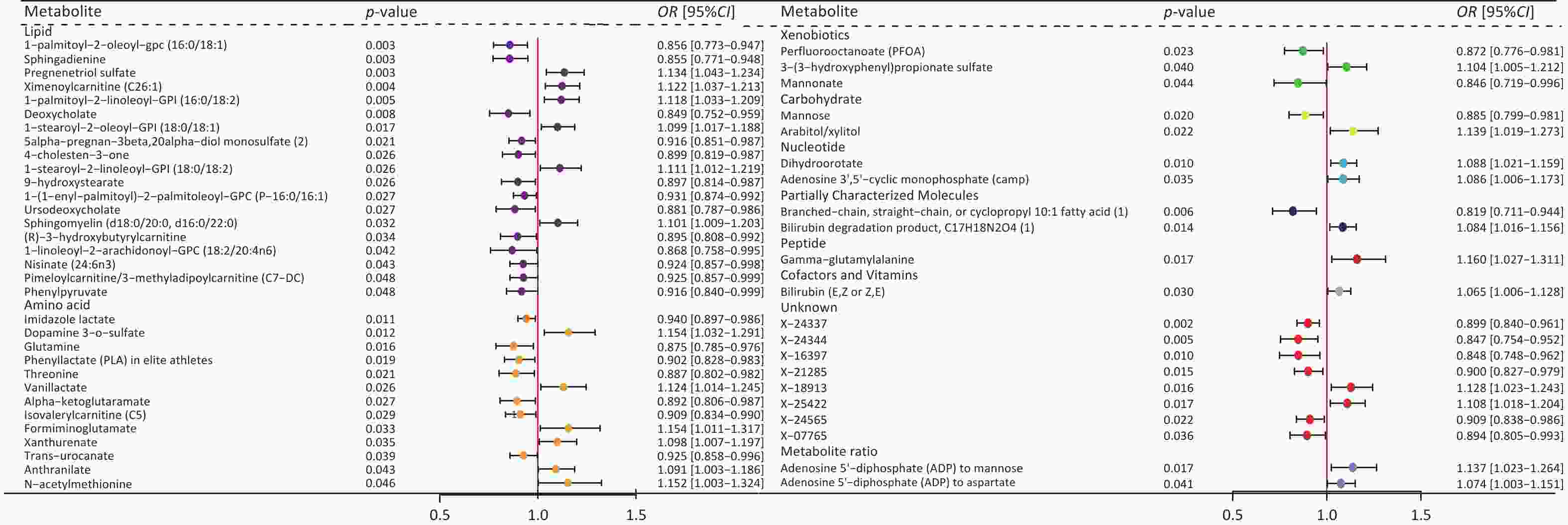

We then conducted UVMR analysis to find blood metabolites associated with MAFLD, identifying those that have causal relationships with the condition. In total, 53 metabolites were identified (Figure 4, Supplementary Table S9). After the MR sensitivity analysis, the results remained reliable (Supplementary Table S10).

Figure 4. Forest plot of causal effects of blood metabolites on MAFLD. Plasma metabolites encompass a diverse array of substances, including lipids, amino acids, xenobiotics, nucleotides, cofactors, and vitamins, as well as carbohydrates, peptides, partially characterized molecules, and unidentified compounds. Additionally, two metabolite ratios are identified. P-value, the P-value of causal estimation in the IVW method; OR [95% CI], odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Subsequently, we performed UVMR analysis between MAFLD-related microbial taxa (20 from the de novo MR analysis and 14 from the meta-analysis) and these 53 MAFLD-related metabolites. As a result, 34 metabolite mediators were successfully identified (Supplementary Table S11).

-

To determine whether these microbiotas exerted their impact on MAFLD risk directly or through the 34 metabolites, we conducted an MVMR analysis. The effect of the majority of the genetically predicted microbiota on MAFLD remained significant and robust after accounting for metabolites (Supplementary Table S12).

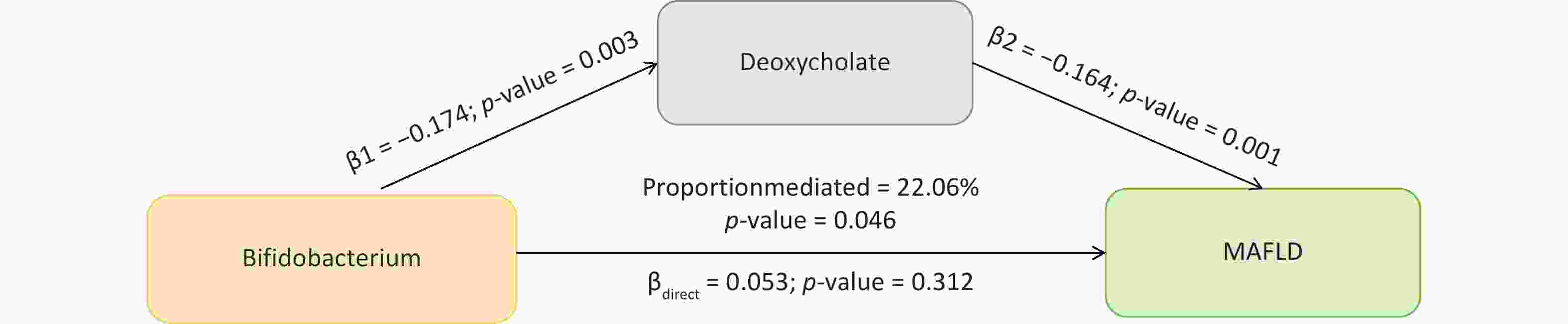

Among these, some gut microbiomes have demonstrated significant mediating effects on the risk of MAFLD through specific metabolites. Notably, the genus Bifidobacterium showed a significant mediated effect through deoxycholate (β2 = −0.165, 95% CI: −0.275 to −0.055, P2 = 0.003), highlighting the involvement of bile acid metabolism in MAFLD pathogenesis. Further, genus CAG-552 was found to be associated with MAFLD via 1-linoleoyl-2-arachidonoyl-GPC 18:2/20:4n6 (β2 = 0.057, 95% CI: −0.102–0.215, P2 = 0.486).

Both direct and mediated effects were observed in some microbiota. For instance, genus CAG-884 was associated with MAFLD directly (β1 = −0.167, 95% CI: −0.292 to −0.042, P1 = 0.009) and via bilirubin degradation product (β2 = 0.065, 95% CI: 0.020–0.111, P2 = 0.005). Additionally, genus CAG-145 exhibited a significant direct effect (β1 = 0.149, 95% CI: 0.006–0.292, P1 = 0.006), suggesting alternative pathways independent of the tested metabolites.

-

In the mediation analysis, we confirmed the mediating role of deoxycholate between Bifidobacterium and MAFLD (mediation effect = 0.028, 95% CI: 0–0.056, P = 0.046), accounting for 22.06% of the total effect and underscoring the critical role of bile acid metabolism in MAFLD pathogenesis (Figure 5). Additionally, other associations were noted; however, their effects did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 5. The mediation effect of gut microbial taxonomy on MAFLD via blood metabolites. β1, the effect of gut microbial taxonomy on the blood metabolites; β2, the effect of the blood metabolite on MAFLD after adjustment for gut microbial taxonomy; βdirect, the direct effect of the gut microbial taxonomy on MAFLD; P-value, the P-value of causal estimation; Proportion mediated (%), the proportion of effect mediated through blood metabolites.

No significant associations were observed at the species level. The overall results of the mediation MR analysis are presented in Supplementary Table S13. The reverse MR analysis further supported these results (Supplementary Table S14).

-

In this study, we employed multiple analytical methods to investigate the relationship between gut microbiota and MAFLD. First, we used de novo MR analysis and identified 25 MAFLD-related microbial taxa, including species-level taxa. After integrating the meta-analysis, we identified 14 robust microbial taxa associated with MAFLD (20 from the de novo analysis were excluded due to no overlap). In total, 34 taxa were identified: 14 from the meta-analysis and 20 from the de novo analysis. Additionally, we identified 53 blood metabolites that were causally related to MAFLD, and the direct and mediated effects of these 34 microbiotas on MAFLD were determined through MVMR analysis. Mediation analysis revealed the role of specific microbiota in the pathogenesis of MAFLD through metabolites. Specifically, deoxycholate mediated 22.06% of the effects of the genus Bifidobacterium on MAFLD.

In the current study, following a meta-analysis, we observed that 14 bacterial taxa exhibited causal associations with MAFLD, with 5 showing negative associations and 9 positive associations. Among these, we validated the negative associations between the genus Defluviitaleaceae UCG011, Intestinibacter, Intestinimonas, Senegalimassilia, and Lachnoclostridium with MAFLD[19,21,29]. In line with previous studies, we also found that the order Actinomycetales[17], the family Actinomycetaceae[20], Oxalobacteraceae[20], as well as the genus Hungatella[19], Oxalobacter[18], Lachnospiraceae[16], Roseburia[30], and Ruminococcaceae[17] were all associated with an increased risk of MAFLD. These taxa have been shown in studies to promote inflammation, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, all of which contribute to MAFLD[31]. However, the association between specific bacterial genera and MAFLD remains unclear. For instance, some study claims that certain strains of Bifidobacterium suppressed MAFLD-related carcinoma progression[32], while some claim that there were no differences in the abundance of Bifidobacterium between the patients with NAFLD and healthy individuals[33]. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrated a positive correlation between Bifidobacterium and MAFLD. Emily et al. [34], through the reverse metabolomics approach, demonstrated that this genus can produce specific bile amide compounds, which can contribute to intestinal inflammation by regulating the production of IFNγ in T cells and activating the pregnane X receptor (PXR)[34]. Intestinal inflammation is known to disrupt the gut-liver axis, leading to an increased risk of fatty liver disease, thus highlighting the potential role of Bifidobacterium in the development and progression of MAFLD.

To strengthen the causal inference, we conducted a bidirectional MR analysis primarily to exclude reverse causality, ensuring that microbial taxa identified in forward MR truly exert a causal effect on MAFLD, rather than reflecting secondary changes due to liver dysfunction. This design helps to isolate microbes with a likely direct pathogenic role. Among the taxa showing bidirectional causal associations, Faecalicatena lactaris and Negativibacillus massiliensis exhibited distinct pathological mechanisms. The taxa F. lactaris was negatively associated with MAFLD risk in forward MR (OR = 0.838, P = 0.004) and was further suppressed by MAFLD in reverse MR (OR = 0.940, P = 0.036), suggesting a vicious cycle. As a butyrate-producing commensal, F. lactaris may protect against liver injury by maintaining the gut barrier integrity and immune balance[35,36]. Its depletion can increase gut permeability and hepatic inflammation, and MAFLD-induced dysbiosis may exacerbate its loss[6]. In contrast, N. massiliensis showed a risk-enhancing effect in forward MR (OR = 1.311, P = 0.038), but was modestly reduced by MAFLD in reverse MR (OR = 0.966, P = 0.013). This pattern suggested a possible initiator role in MAFLD development, potentially through proinflammatory metabolites or bile acid disruption[37], but with limited persistence in advanced disease due to host feedback responses. These findings emphasize the complexity of gut-liver interactions, where certain taxa may trigger disease onset, while others sustain or protect against disease progression. Disrupting such feedback loops may offer novel therapeutic opportunities.

Additionally, we identified several novel microbial taxa associated with MAFLD that had not been previously implicated. Among these, Lactococcus lactis has drawn our attention, primarily due to its production of nisin, an antimicrobial peptide that has been shown to regulate glycolipid metabolism and alleviate hepatic inflammation[38]. Our results provided novel evidence, demonstrating a significant causal protective effect of L. lactis on fatty liver (OR [95% CI] = 0.73 [0.58–0.917], P = 0.007), thereby highlighting its potential as a therapeutic choice of MAFLD. However, further experimental studies are needed to validate these associations and explore the specific biological processes underlying their roles in MAFLD pathogenesis. Other species, such as Faecalicatena lactaris, Negativibacillus massiliensis, Prevotella buccae, and Lachnospiraceae bacterium, have been studied, but we are the first to report their associations with MAFLD.

Furthermore, our study revealed that the effect of Bifidobacterium on MAFLD risk was partially mediated by deoxycholate (22.6%). We discovered that deoxycholate is associated with reduced MAFLD risk (OR [95% CI] = 0.85 [0.75–0.96], P = 0.008). This result was expected, considering the unique properties and functions of deoxycholate. Deoxycholate, a crucial constituent of bile salt, enters the intestinal cavity via the biliary tract, emulsifies fat, and fragments it into minute fat particles[39]. Recent research has suggested its potential applications in fat dissolution and obesity treatment[40]. In vitro experiments on human subcutaneous adipocytes demonstrated that bile salt particles required 3 h to eliminate fat cells completely; however, deoxycholate achieved the same result within just one hour[40]. Moreover, subcutaneous injection of deoxycholate into the inguinal fat pads of genetically obese mice led to a reduction in local fat mass without giving rise to any adverse side effects[40]. Regarding the mediation pathway, Bifidobacterium can break down bile salts; the released bile acids then undergo decarboxylation to form deoxycholic acid[41]. Most of the deoxycholic acid is excreted in feces[41]. Bifidobacterium is sensitive to bile acid levels in feces. When the concentration of deoxycholic acid is high, it will exert a bactericidal effect on Bifidobacterium[42]. Consequently, it is likely that the genus Bifidobacterium augments susceptibility to MAFLD by reducing deoxycholate levels. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium has diverse ways of impacting MAFLD, and this effect is often species-specific[43]. Therefore, to better understand the intricate interplay between Bifidobacterium and its metabolites, it is essential to conduct species-level taxonomic studies, especially within the taxonomic reclassification of the Bifidobacterium genus. Further studies on specific strains and their metabolic functions in various host environments are essential to fully elucidate these complex interactions.

The key strengths of our study include a detailed species-level gut microbiota analysis and a comprehensive summary of current GWAS data regarding gut microbiome. Despite the comprehensive nature of our study, it has limitations. The first is related to the representativeness of the cohorts. Our analysis was mainly based on European ancestry cohorts due to the current lack of large-scale microbiome GWAS data for Asian and African populations. This limitation stems from the restricted availability of public datasets rather than the study design. As microbiome research expands globally, future studies involving more diverse populations will be essential to validate and generalize these findings. Second, as our MR framework relies on summary-level GWAS data, we were unable to directly adjust for individual-level covariates, such as dietary patterns and antibiotic or proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, which are known to influence gut microbiota composition. While MR helps reduce confounding by design, the potential for residual confounding cannot be fully excluded. Third, blood metabolomics cannot distinguish between hepatic and intestinal origins of deoxycholate levels. However, the current lack of publicly available GWAS datasets for fecal bile acids prevents their integration into MR frameworks.

-

In this study, we performed a de novo MR analysis and meta-analysis using published MR studies to identify 34 types (10 at the species level) of microbial taxa that contribute to the development of MAFLD, of which 19 taxa increased MAFLD risk and 15 decreased MAFLD risk. In addition, we found that specific metabolites mediated these associations. Future studies are warranted to elucidate the potential mechanisms of action between specific microbial taxa and MAFLD.

doi: 10.3967/bes2025.162

Decoding Links Between Gut Microbiota and Metabolic-associated Fatty Liver Disease: Meta-Analysis and Mediation Study Uncover Species-Specific Taxa and a Novel Bile Acid Mediator

-

Abstract:

Objective Previous Mendelian randomization (MR) studies have suggested an association between the gut microbiome and metabolic - associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD). However, the reliance on 16S rRNA sequencing data has led to inconsistent findings and limited species-level insights. To address this, we conducted a de novo MR analysis using species-level shotgun metagenomic data, combined it with a meta-analysis to consolidate the existing evidence, and explored metabolite-mediated pathways. Methods Bidirectional MR analyses were performed between 883 gut microbiota taxa (derived from shotgun metagenomic genome-wide association study) and MAFLD. Published MR studies (up to December 1, 2024) were identified using PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for meta-analysis. Multivariable MR (MVMR) and mediation analyses were applied to assess the mediating effects of 1,400 blood metabolites. Results The de novo MR identified 25 MAFLD-associated microbial taxa. Integration with 7 published studies revealed 34 causal taxa, including 10 at the species level. Among the 1,400 metabolites, 53 showed causal links with MAFLD. MVMR and mediation analyses identified deoxycholate as a mediator of the effect of Bifidobacterium on MAFLD risk (22.06% mediation proportion). Conclusion This study elucidated the connections between species-level gut microbiota and MAFLD, highlighting the interplay between microbiota, metabolites, and disease pathogenesis. These findings provide novel insights into the potential therapeutic targets for MAFLD. -

Key words:

- Gut microbiome /

- Metabolic - associated fatty liver disease /

- Causal associations /

- Mendelian randomization /

- Meta-analysis.

All authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Not applicable.

&These authors contributed equally to this work.

注释:1) Authors’ Contributions: 2) Competing Interests: 3) Ethics: -

Figure 2. Forest plot of bidirectional causal effects between gut microbial taxa and MAFLD (P < 0.05). (A) Causal effects of gut microbial taxa on MAFLD; (B) Causal effects of MAFLD on gut microbial taxa. SNPs, number of SNPs; SE, standard error of coefficient estimate; P-value, the P-value of causal estimation in the IVW method; OR [95% CI], odds ratio and 95% confidence interval; Heterogeneity, the P-value of heterogeneity analysis; Pleiotropy, the P-value of horizontal pleiotropy analysis.

Figure 3. Forest plot of the meta-analysis of gut microbial taxa and MAFLD. (A) Intersection of three gut microbiome datasets. Grey circles: taxa not significantly associated with MAFLD. Blue, pink, green circles: taxa significantly associated with MAFLD. (B) Overall meta-analysis results, the gut microbiota in the dashed boxes were included in the meta-analysis. Red: consistently statistically associated with MAFLD after meta-analysis. Black: not significantly associated after meta-analysis. (C) Meta-analysis forest plot at the genus level. (D) Meta-analysis forest plot at the family level. (E) Meta-analysis forest plot at the order and class level. Source, gut microbial taxa; SNPs, number of SNPs; P-value, the P-value of causal estimation in the IVW method; OR [95% CI], odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Figure 4. Forest plot of causal effects of blood metabolites on MAFLD. Plasma metabolites encompass a diverse array of substances, including lipids, amino acids, xenobiotics, nucleotides, cofactors, and vitamins, as well as carbohydrates, peptides, partially characterized molecules, and unidentified compounds. Additionally, two metabolite ratios are identified. P-value, the P-value of causal estimation in the IVW method; OR [95% CI], odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Figure 5. The mediation effect of gut microbial taxonomy on MAFLD via blood metabolites. β1, the effect of gut microbial taxonomy on the blood metabolites; β2, the effect of the blood metabolite on MAFLD after adjustment for gut microbial taxonomy; βdirect, the direct effect of the gut microbial taxonomy on MAFLD; P-value, the P-value of causal estimation; Proportion mediated (%), the proportion of effect mediated through blood metabolites.

-

[1] Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology, 2016; 64, 73−84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431 [2] Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol, 2020; 73, 202−9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039 [3] Colaci C, Gambardella ML, Scarlata GGM, et al. Dysmetabolic comorbidities and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a stairway to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatoma Res, 2024; 10, 16. doi: 10.20517/2394-5079.2023.134 [4] Aron-Wisnewsky J, Vigliotti C, Witjes J, et al. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020; 17, 279−97. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0269-9 [5] Wang LJ, Zhang K, Zeng YJ, et al. Gut mycobiome and metabolic diseases: the known, the unknown, and the future. Pharmacol Res, 2023; 193, 106807. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106807 [6] Tilg H, Adolph TE, Trauner M. Gut-liver axis: pathophysiological concepts and clinical implications. Cell Metab, 2022; 34, 1700−18. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.09.017 [7] Pabst O, Hornef MW, Schaap FG, et al. Gut-liver axis: barriers and functional circuits. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023; 20, 447−61. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00771-6 [8] Brandl K, Schnabl B. Intestinal microbiota and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2017; 33, 128−33. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000349 [9] Forlano R, Martinez-Gili L, Takis P, et al. Disruption of gut barrier integrity and host-microbiome interactions underlie MASLD severity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Gut Microbes, 2024; 16, 2304157. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2304157 [10] Lee G, You HJ, Bajaj JS, et al. Distinct signatures of gut microbiome and metabolites associated with significant fibrosis in non-obese NAFLD. Nat Commun, 2020; 11, 4982. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18754-5 [11] Leung H, Long XX, Ni YQ, et al. Risk assessment with gut microbiome and metabolite markers in NAFLD development. Sci Transl Med, 2022; 14, eabk0855. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abk0855 [12] Burgess S, Timpson NJ, Ebrahim S, et al. Mendelian randomization: where are we now and where are we going?. Int J Epidemiol, 2015; 44, 379−88. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv108 [13] Jovel J, Patterson J, Wang WW, et al. Characterization of the gut microbiome using 16S or shotgun metagenomics. Front Microbiol, 2016; 7, 459. [14] Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat Genet, 2021; 53, 156−65. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00763-1 [15] Zhang LL, Zi LL, Kuang TR, et al. Investigating causal associations among gut microbiota, metabolites, and liver diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol, 2023; 14, 1159148. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1159148 [16] Zhai QL, Wu HY, Zheng SY, et al. Association between gut microbiota and NAFLD/NASH: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2023; 13, 1294826. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1294826 [17] Li Y, Liang XF, Lyu Y, et al. Association between the gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Dig Liver Dis, 2023; 55, 1464−71. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2023.07.014 [18] Ouyang C, Liu PP, Liu YW, et al. Metabolites mediate the causal associations between gut microbiota and NAFLD: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Gastroenterol, 2024; 24, 244. doi: 10.1186/s12876-024-03277-w [19] Dai XY, Jiang KP, Ma XJ, et al. Mendelian randomization suggests a causal relationship between gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in humans. Medicine, 2024; 103, e37478. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037478 [20] Pan TT, Su LH, Zhang YY, et al. Impact of gut microbiota on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: insights from a leave-one-out cross-validation study. Front Microbiol, 2023; 14, 1320279. [21] Dai WH, Cai DD, Zhou S, et al. Uncovering a causal connection between the Lachnoclostridium genus in fecal microbiota and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Front Microbiol, 2023; 14, 1276790. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1276790 [22] Lopera-Maya EA, Kurilshikov A, Van Der Graaf A, et al. Effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome in 7, 738 participants of the Dutch Microbiome Project. Nat Genet, 2022; 54, 143−51. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00992-y [23] Qin YW, Havulinna AS, Liu Y, et al. Combined effects of host genetics and diet on human gut microbiota and incident disease in a single population cohort. Nat Genet, 2022; 54, 134−42. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00991-z [24] Miele L, Zocco MA, Pizzolante F, et al. Use of imaging techniques for non-invasive assessment in the diagnosis and staging of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism, 2020; 112, 154355. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154355 [25] Ghodsian N, Abner E, Emdin CA, et al. Electronic health record-based genome-wide meta-analysis provides insights on the genetic architecture of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Rep Med, 2021; 2, 100437. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100437 [26] Chen YH, Lu TY, Pettersson-Kymmer U, et al. Genomic atlas of the plasma metabolome prioritizes metabolites implicated in human diseases. Nat Genet, 2023; 55, 44−53. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01270-1 [27] Sekula P, Del Greco MF, Pattaro C, et al. Mendelian randomization as an approach to assess causality using observational data. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016; 27, 3253−65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010098 [28] Sanderson E. Multivariable mendelian randomization and mediation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2021; 11, a038984. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a038984 [29] Yu GJ, Chen QL, Chen JX, et al. Gut microbiota alterations are associated with functional outcomes in patients of acute ischemic stroke with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Neurosci, 2023; 17, 1327499. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1327499 [30] Liu GH, Zhao QX, Wei HY. Characteristics of intestinal bacteria with fatty liver diseases and cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol, 2019; 18, 796−803. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.06.020 [31] Michels N, Zouiouich S, Vanderbauwhede B, et al. Human microbiome and metabolic health: an overview of systematic reviews. Obes Rev, 2022; 23, e13409. doi: 10.1111/obr.13409 [32] Song Q, Zhang X, Liu WX, et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-generated acetate suppresses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol, 2023; 79, 1352−65. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.005 [33] Li FX, Ye JZ, Shao CX, et al. Compositional alterations of gut microbiota in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis, 2021; 20, 22. doi: 10.1186/s12944-021-01440-w [34] Gentry EC, Collins SL, Panitchpakdi M, et al. Reverse metabolomics for the discovery of chemical structures from humans. Nature, 2024; 626, 419−26. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06906-8 [35] Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol, 2017; 19, 29−41. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13589 [36] Rivière A, Selak M, Lantin D, et al. Bifidobacteria and butyrate-producing colon bacteria: importance and strategies for their stimulation in the human gut. Front Microbiol, 2016; 7, 979. [37] Qin N, Yang FL, Li A, et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature, 2014; 513, 59−64. doi: 10.1038/nature13568 [38] Kuraji R, Ye CC, Zhao CJ, et al. Nisin lantibiotic prevents NAFLD liver steatosis and mitochondrial oxidative stress following periodontal disease by abrogating oral, gut and liver dysbiosis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes, 2024; 10, 3. doi: 10.1038/s41522-024-00476-x [39] Macierzanka A, Torcello-Gómez A, Jungnickel C, et al. Bile salts in digestion and transport of lipids. Adv Colloid Interface Sci, 2019; 274, 102045. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2019.102045 [40] Horejs C. Bile salt particles locally dissolve fat. Nat Rev Mater, 2021; 6, 107. [41] Yoon JH, Do JS, Velankanni P, et al. Gut microbial metabolites on host immune responses in health and disease. Immune Netw, 2023; 23, e6. doi: 10.4110/in.2023.23.e6 [42] Alenezi T, Alrubaye B, Fu Y, et al. Recombinant bile salt hydrolase enhances the inhibition efficiency of taurodeoxycholic acid against Clostridium perfringens virulence. Pathogens, 2024; 13, 464. doi: 10.3390/pathogens13060464 [43] Wang LL, Jiao T, Yu QQ, et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum shows more diversified ways of relieving non-alcoholic fatty liver compared with bifidobacterium adolescentis. Biomedicines, 2021; 10, 84. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10010084 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links