-

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), remains one of the most significant global public health challenges and ranks among the deadliest infectious diseases[1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Tuberculosis Report 2024, approximately 10.8 million new TB cases were reported worldwide in 2023, with 1.25 million deaths attributed to the disease, and TB has re-emerged as the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent globally[2]. The rise in drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) further complicates the global TB epidemic. Of particular concern are multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB), which together account for approximately 400,000 cases by 2023[2]. This situation is further compounded by the progressive emergence of resistance to newer drugs, such as bedaquiline and clofazimine, which were initially regarded as promising tools for combating resistant strains[3].

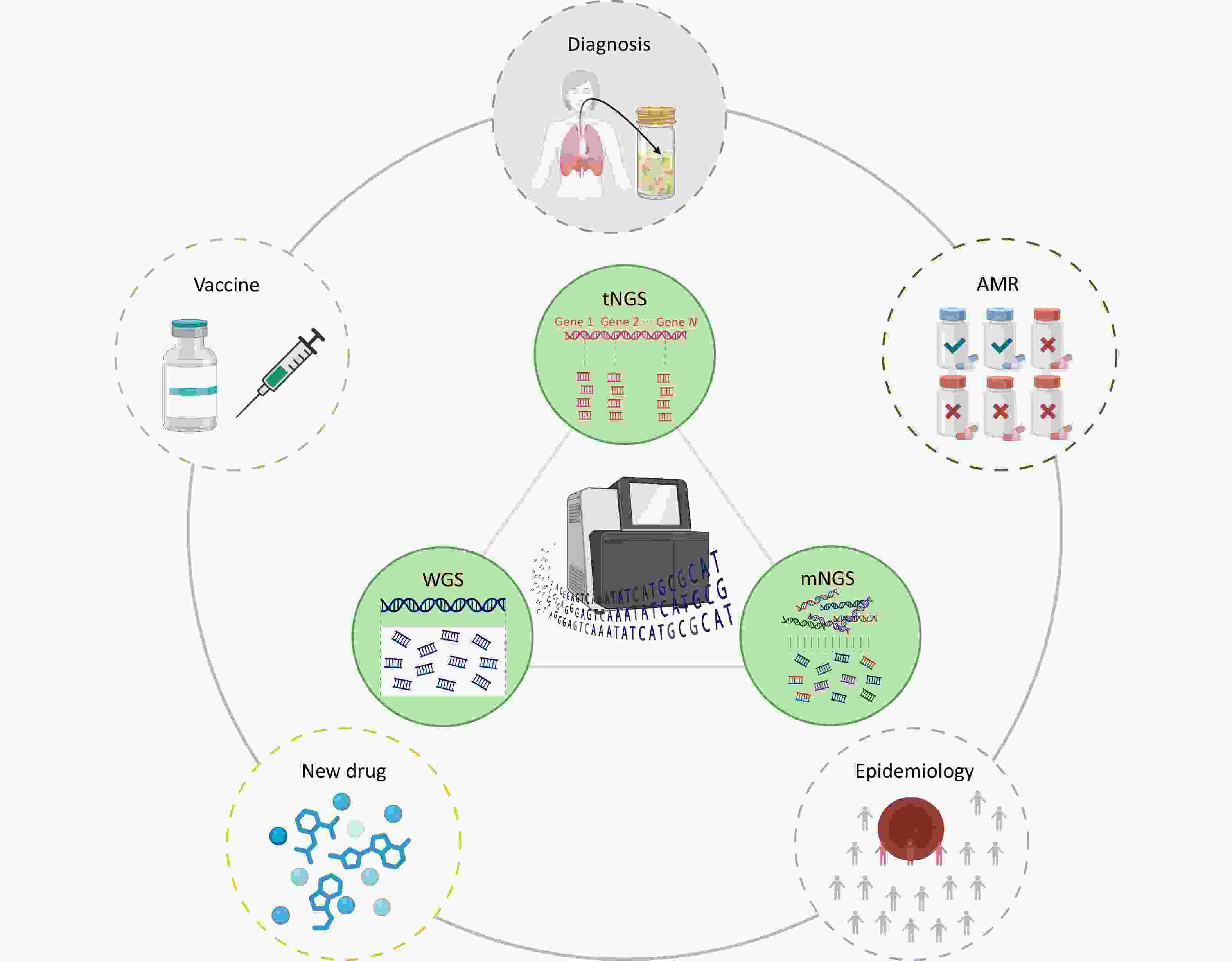

Rapid and accurate identification of pathogens and their antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles is essential for the effective treatment of TB and control of pathogen transmission[4]. Although bacterial culture and phenotypic drug susceptibility testing (pDST) remain the gold standard methods for confirming TB diagnosis and determining AMR, their prolonged turnaround times (up to several weeks) significantly delay clinical decision-making and treatment initiation[5,6]. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), including methods based on real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), line probe assays (LPA), and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), have significantly improved diagnostic speed and accuracy. However, these methods only detect predefined and validated resistance mutations, thereby restricting their diagnostic breadth[7,8]. To overcome these limitations, high-throughput sequencing (HTS) has emerged as a transformative tool for the comprehensive analysis of TB pathogens[9–12]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in HTS technology as applied to TB research. We examined various methodologies developed using different sequencing platforms and strategies for pathogen identification, AMR analysis, epidemiological research, and the development of novel drugs and vaccines (Figure 1). Furthermore, we critically assessed the current limitations and explored the potential to enhance TB diagnosis, treatment strategies, and public health interventions.

Figure 1. High throughput sequencing strategies for tuberculosis management are categorized into three complementary approaches based on analytical scope: targeted next generation sequencing, metagenomic next generation sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing. These strategies are applied in tuberculosis for pathogen diagnosis, antimicrobial resistance detection, epidemiology research, and the development of new drugs and vaccines.

-

HTS, also referred to as next-generation sequencing (NGS), has profoundly influenced TB research and diagnostics by enabling comprehensive genomic analyses with exceptional resolution and throughput[13,14]. Short-read sequencing platforms, including those offered by Illumina, BGI, and Ion Torrent, remain indispensable for MTBC investigations owing to their high base-level accuracy, cost-effectiveness in large-scale studies, and robust performance in variant calling for AMR profiling. However, short-read technologies face inherent challenges in resolving complex genomic regions and assembling complete genomes, thereby limiting their utility in certain applications[15-19]. The advent of long-read sequencing platforms such as Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing from PacBio and nanopore sequencing from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) represents a significant advancement in HTS. These platforms can overcome the inherent limitations of short-read methods by generating thousands of base pairs. This capability is crucial for resolving complex genomic regions, including structural variants and repetitive elements, thereby enabling the assembly of complete high-quality genomes. Furthermore, nanopore technology introduces unique advantages such as real-time data analysis and true instrument portability, as exemplified by MinION. This combination provides unparalleled flexibility, making these tools invaluable for rapid point-of-need diagnostics in resource-limited or field settings where timely pathogen detection is critical[20-22] (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparative overview of HTS platforms for TB research

Manufacturer Representative Instruments Technology Read Length Accuracy Advantages Limitations Typical Applications Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq, NovaSeq Short-read sequencing 50–300 bp > 99.9% High throughput, cost-effective; widely used Short reads; limited complex region assembly Large-scale AMR profiling; epidemiological studies BGI MGISEQ-2000, DNBSEQ-T7 Short-read sequencing 50–400 bp > 99.9% High throughput; cost-effective Short reads; limited complex region assembly AMR surveillance; population-scale pathogen studies Ion Torrent Ion PGM, Ion Proton, Ion S5 Semiconductor sequencing 200–600 bp ~ 99.9% Rapid; flexible; suitable for clinical use Error-prone in homopolymer regions Rapid diagnostics; targeted AMR mutation detection PacBio Sequel IIe, Revio Single Molecule, Real-Time Sequencing 10–20 kb > 99.9% Long reads; high accuracy; good assembly Higher cost; lower throughput High-quality genome assemblies; complex genomic studies ONT MinION, GridION, PromethION Long-read nanopore sequencing 5–50 kb ~ 99.9% Portable; rapid results; real-time sequencing Higher error rate in homopolymer regions Field diagnostics, real-time AMR mutation detection HTS strategies for TB management can be broadly classified into three complementary approaches based on their analytical scope: targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS), metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), and whole-genome sequencing (WGS)[23] (Table 2). tNGS focuses on specific gene regions by capturing target genes and subsequently performing HTS. This approach is especially suited for patients with clinical suspicion of TB infection. It not only aids in TB diagnosis, but also detects AMR mutations, providing clinicians with precise therapeutic guidance. Therefore, tNGS offers a cost-effective alternative to conventional pDST for populations that require detailed resistance profiling in targeted settings[24,25]. In contrast, mNGS utilizes a culture-independent, hypothesis-free approach for pathogen detection through a shotgun metagenomic analysis of total nucleic acids. Its principal advantage lies in its ability to identify fastidious pathogens and polymicrobial infections, which is particularly valuable in atypical clinical scenarios in which TB infection is not definitive or co-infections are suspected. By comprehensively sequencing all the genomic materials present in a sample, mNGS can simultaneously detect Mycobacterium species, other pathogens, and host nucleic acids without prior enrichment[26]. WGS, regarded as the gold standard for delineating complete genetic landscapes, enables simultaneous AMR prediction, strain typing, and evolutionary analysis by resolving the entire mycobacterial genome at a base-pair resolution. Although WGS is predominantly used in reference laboratories for outbreak investigations and elucidation of resistance mechanisms, improvements in cost-effectiveness are increasingly promoting its adoption to guide personalized therapy in complex MDR-TB cases[27-29]. Taken together, these HTS methods create a diagnostic spectrum that supports rapid clinical decisions using tNGS, thorough pathogen profiling using mNGS, and targeted public health actions using WGS. This combined approach is transforming TB management into the genomic era.

Table 2. Comparative overview of HTS strategies in TB research

Strategy Scope Detection Coverage Advantages Limitations Typical Applications tNGS Selected resistance-associated genes or regions Known AMR targets Rapid; cost-effective; clinically actionable Limited targets; incomplete genomic data Rapid AMR diagnosis; clinical resistance profiling mNGS Unbiased sequencing of total DNA/RNA from clinical samples Broad pathogen detection (known/unknown, mixed infections) Hypothesis-free; comprehensive pathogen detection High cost; complex analysis; lower sensitivity for low-abundance pathogens Complex or unclear cases; pathogen discovery WGS Entire MTBC genome Comprehensive genomic information Complete genomic data; gold standard for AMR profiling and epidemiology Higher cost; complex data analysis; longer turnaround AMR mechanism research; outbreak tracking; public health surveillance -

MTBC is the primary cause of TB. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical to control disease transmission and ensure timely treatment. HTS technologies have significantly advanced TB diagnostics, offering a precise, rapid, and culture-independent approach for pathogen detection.

Compared with traditional diagnostic methods, mNGS provides substantial improvements in both efficiency and speed. Although conventional methods may take up to 90 days to identify TB infections and often detect fewer than 50% of cases, mNGS can identify TB in up to 67.23% of cases within three days[30]. This substantial reduction in the diagnostic time underscores the potential of mNGS as a promising approach for early and accurate TB detection. Several studies have highlighted the superior diagnostic performance of mNGS for TB detection. For example, one study compared mNGS, traditional culture, and GeneXpert MTB/RIF in 70 suspected TB cases. The results showed that mNGS demonstrated superior sensitivity (66.7%) and specificity (97.1%) for detecting TB, outperforming both culture methods and GeneXpert[31]. Moreover, an mNGS method utilizing the ONT platform demonstrated even higher detection accuracy, achieving a sensitivity of 94.8% and a specificity of 97.9% for pulmonary TB[32]. Combining mNGS with culture or GeneXpert has been shown to enhance diagnostic efficacy, particularly in pulmonary TB cases. This integrated approach is promising for clinical applications, offering a comprehensive, rapid, and accurate method for TB detection[30,33,34].

-

A major challenge in TB diagnosis, particularly for paucibacillary pulmonary tuberculosis (PPTB) and tuberculous meningitis (TBM), is the low sensitivity of conventional diagnostic methods. Diagnosing TBM relies on detecting MTBC in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); however, low MTBC load in the CSF often leads to insufficient detection, hindering early microbiological diagnosis. Thus, mNGS demonstrates considerable potential. A meta-analysis demonstrated that mNGS achieved a combined sensitivity of 62% and a specificity of 99%, underscoring its potential for early and accurate TBM diagnosis[35]. To further enhance the diagnostic performance, researchers have proposed combining tNGS with machine learning. This approach, which analyzed CSF DNA and plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) samples, showed significantly improved results across 227 samples. The sensitivity for CSF samples reached 97.01% with a specificity of 95.65%, whereas plasma cfDNA samples exhibited a sensitivity and specificity of 82.61% and 86.36%, respectively. In patients with PPTB, this diagnostic strategy demonstrated higher sensitivity in plasma specimens than the Xpert assay in gastric lavage (28.57% vs. 15.38%)[36]. This innovative approach not only enhances the detection sensitivity for PPTB but also highlights plasma cfDNA as an easily accessible and valuable sample type for diagnosing both PPTB and TBM.

-

DR-TB presents a substantial obstacle to achieving the global goal of eradicating the TB epidemic by 2035[37]. Among HTS technologies, tNGS has emerged as the preferred method for AMR detection in TB. Its ability to perform rapid and comprehensive sequencing directly from clinical samples allows for the detection of AMR mutations with high accuracy. tNGS can efficiently target multiple resistance genes, enabling simultaneous assessment of susceptibility to various anti-TB drugs in a single test[38].

The use of tNGS for AMR detection in TB has been proven to be highly effective in various clinical settings. Among the established and commercially available tNGS methods, the Deeplex® Myc-TB assay, originally developed on the Illumina platform, is particularly notable. This assay provides comprehensive resistance profiles for 13 anti-TB drugs within 48 h, bypassing the need for traditional culture methods. The Deeplex® Myc-TB assay has been validated in numerous studies for its clinical utility, and it also identifies over 100 species of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) as well as a broad range of lineages and spoligotypes within the MTBC. Furthermore, Deeplex® Myc-TB, which relies on targeted deep sequencing and automated analysis through secure web platforms, is capable of accurately detecting heteroresistance at levels as low as 1%–3%[15-19]. With the rapid development of third-generation sequencing technologies, there has been increasing interest in adapting the Deeplex® Myc-TB assay for use with ONT platforms. However, initial attempts to apply Deeplex® Myc-TB directly to ONT have revealed some challenges. Specifically, achieving the same variant-detection accuracy as that of the Illumina platform requires a sequencing depth of at least 40X[15]. Although this depth is necessary for reliable results, it limits the number of samples that can be processed in a single-flow cell, thus restricting the scalability of ONT-based testing for high-throughput clinical settings. Additionally, the short amplicons used in the Deeplex® Myc-TB assay did not fully leverage the ultra-long read capabilities of ONT, resulting in suboptimal performance. In response to these challenges, several long-amplicon-based tNGS methods have been developed specifically for ONT platforms and have shown improved performance. These methods, optimized for ONT ultralong reads, enhance sequencing accuracy and broaden the coverage of resistance targets, leading to improved diagnostic outcomes and faster turnaround times. ONT-based tNGS methods significantly reduce turnaround times, with results potentially available in just one day, owing to their rapid library preparation and real-time data analysis capabilities[15,23,39-45]. The latest tNGS method, optimized for ONT, achieved 100% concordance in sequencing accuracy with the Illumina platform. The AMR prediction accuracy of this method reached 98.35% compared with pDST and 100% compared with GeneXpert MTB/RIF, with an overall turnaround time of less than 5 h[46]. Further innovations in ONT nanopore sequencing have enhanced its utility for TB AMR detection. For instance, one study combined targeted isothermal amplification with nanopore sequencing on the MinION platform, achieving 96.3% sensitivity and 100% specificity for detecting rifampicin resistance genes and 100% sensitivity and specificity for identifying isoniazid resistance genes[47].

tNGS methods have demonstrated superior performance compared with other detection techniques, especially when applied to challenging samples characterized by low bacterial loads, suboptimal quality, or those that are difficult to culture. For instance, a recent study developed an ONT-targeted panel for the direct detection of TB drug resistance, which successfully retrieved full sequencing data from nearly half of low MTBC burden specimens. With a turnaround time of just 6–9 hours, this method represents a significant improvement over traditional pDST[41]. While formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples are widely used because of their stability, affordability, and safety, they present challenges due to DNA degradation and the predominance of host DNA over MTBC DNA. Despite these obstacles, studies have demonstrated that tNGS excels in detecting resistance to rifampicin and isoniazid in FFPE samples, achieving sensitivities of 96% and 94%, respectively, with a specificity exceeding 95%. This capability enhances the detection of drug resistance in smear-negative and extrapulmonary TB cases[48]. Additionally, tNGS has been employed to detect spinal tuberculosis in clinical samples, achieving a 100% detection rate, surpassing traditional culture methods, and accurately identifying multiple drug resistance loci. These findings emphasize the superior ability of tNGS to detect resistant strains in difficult-to-culture samples, further highlighting its potential for broad clinical application[49].

-

HTS has become an indispensable tool in TB epidemiology, enabling precise tracking of the transmission pathways of MTBC, revealing the dynamics of the spread of resistant strains, and identifying key epidemiological patterns. WGS is particularly prominent in this field owing to its superior discriminatory power. Unlike traditional genotyping techniques, WGS allows the precise identification of MTBC strains and subtypes by analyzing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and genomic deletions[50]. The application of WGS extends beyond static outbreak investigations to ongoing genomic surveillance. By sequencing isolates from a community or an outbreak over time, public health laboratories can perform real-time mutation tracking to monitor the emergence and spread of specific drug-resistant mutations. This longitudinal approach provides an unprecedented view of resistance evolution, acting as an early warning system for the emergence of new high-risk strains (e.g., MDR- or XDR-TB) and allowing for rapid public health interventions. This comprehensive genomic profiling not only improves the accuracy of TB strain identification but also provides valuable insights into the genetic factors driving resistance and transmission dynamics[51].

Researchers worldwide have developed several automated analysis tools that enable genome variation detection, strain identification, and resistance prediction by simply importing raw sequencing data. Among these, TB-Profiler is widely used because of its customizable mutation database and support of long-read sequences, thereby improving the accuracy of resistance detection[52]. Mykrobe is known for its fast analysis and user-friendly interface; however, it offers fewer downstream analysis features[53]. SAM-TB provides a comprehensive platform for MTBC analysis, including lineage identification, resistance prediction, and phylogenetic tree reconstruction[54]. These tools typically employ direct association methods by screening for known AMR mutations and perform well as first-line drugs with well-defined resistance mechanisms. However, the true frontier of genomic analysis lies in the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) algorithms for resistance prediction. Unlike traditional tools, ML-based methods can analyze the entire genomic context to identify complex genetic patterns and interactions. This enables them to not only achieve superior accuracy for both first- and second-line drugs, but also identify novel, previously uncharacterized resistance mutations[55]. This predictive capability represents a significant leap forward, moving the field from simple variant detection to intelligent genomic interpretation.

WGS has enabled rapid monitoring of MTBC transmission. When combined with molecular evolution algorithms, WGS can infer transmission direction and chains, thereby aiding in the identification of transmission direction and chains, and helping to identify sources of infection and missing links in transmission. Given the limited genetic diversity of MTBC, thresholds of 5 or 12 SNP differences are typically used to indicate epidemiological connections. Emerging genomic tools are transforming our approach to MTBC transmission detection by enhancing SNP resolution and refining transmission-event estimates. Pa-genome based Pairwise SNP comparison (PANPASCO) is a genetic distance calculation method based on a linear pan-genome map that effectively reduces alignment losses between strains of different lineages and improves SNP detection resolution. In multiple-dataset tests, PANPASCO demonstrated better transmission detection results than traditional methods, showing strong universality and suitability for large-scale sample transmission detection[56]. Transcluster is another tool used to identify recent transmission clusters by estimating the probability and number of transmission events based on strain transmission rates, sampling intervals, and SNP differences between genomes[57]. These WGS-based methods have been proven to outperform contact tracing and offer higher resolution than classic genotyping methods, such as variable numbers of tandem repeat (VNTR) typing. These WGS-based methods can be used to identify recent transmission clusters, and can be further explored using molecular evolution approaches to infer the transmission network within a cluster. Tools, such as SeqTrack and TransPhylo, are commonly used for this purpose. SeqTrack was one of the earliest tools used to build transmission networks based on a global transmission tree, whereas TransPhylo incorporates epidemiological data, considering the evolutionary status of strains within their hosts, to provide a more comprehensive view of the transmission network[58,59].

In addition, research indicates that the application of ONT sequencing in MTBC epidemiological surveillance is becoming increasingly widespread. Despite the relatively high error rate of ONT, the data generated can still be effectively utilized in epidemiological studies, phylogenetic analysis, and drug resistance detection, providing valuable support for tuberculosis control efforts, especially in high-burden regions[60]. Archetypal scenarios, synthesized from the findings of numerous real-world studies, illustrate how different HTS methodologies provide actionable insights across the spectrum of TB control, from managing individual critically ill patients to controlling community-wide outbreaks (Table 3)[35,36,56,61,62].

Table 3. Comparative case studies on the application of HTS in TB management

Parameter Case 1: Critical MDR-TB Diagnosis Case 2: Public Health Outbreak Case 3: Paucibacillary TBM Diagnosis Clinical Scenario Critically ill, smear-negative pneumonia patient failing standard treatment;

high suspicion of MDR-TBA cluster of TB cases reported in a homeless shelter, requiring investigation of transmission links Patient with subacute neurological symptoms;

high suspicion of TBM but inconclusive initial testsSample Type Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid Sputum isolates from confirmed cases Cerebrospinal fluid HTS Strategies mNGS WGS tNGS Conventional TAT* 4–6 weeks 1–2 weeks Up to 6 weeks HTS TAT* 48 hours 3–5 days 72 hours Key HTS Findings Definitive detection of MTBC DNA;

Profiling of AMR mutationsSix of seven isolates formed a transmission cluster (≤ 5 SNPs), while the seventh was a genetically distinct outlier excluded from the outbreak Definitive detection of low-level MTBC DNA, confirming TBM where all other methods failed Clinical/Public Health Impact Immediate initiation of a life-saving, targeted second-line drug regimen Enabled a focused contact tracing investigation;

Prevented misallocation of resources;

Interrupted the chain of transmissionProvided a definitive diagnosis, allowing for confident initiation of anti-TB therapy;

Prevented severe neurological sequelae and avoided invasive brain biopsyPrimary HTS Advantage Speed & Comprehensiveness Resolution & Precision Sensitivity & Accuracy Note. *TAT, Turnaround Time. -

Owing to the evolving AMR of MTBC and the increasing challenges of MDR-TB and XDR-TB, there is a critical need to accelerate the development of new drugs[63]. HTS plays a pivotal role in this process, offering significant potential for identifying novel drug targets and providing a more precise molecular foundation for the design of new drugs. This technology not only aids in the discovery of genetic mutations associated with drug resistance but also facilitates a deeper understanding of the pathogen’s resistance mechanisms[64]. Integrating HTS data with drug susceptibility information to develop robust predictive models for drug resistance is a vital research focus for TB prevention and treatment. Such advancements are expected to guide the design of more effective targeted therapies and contribute to combating the global TB crisis[65].

HTS plays a crucial role in vaccine research by providing valuable insights into the selection and design of vaccine targets. Recently, a study utilized single-cell and high-throughput TCR deep-sequencing technologies have been used to analyze the T-cell receptor repertoire following TB infection. This study employed novel analytical methods, such as GLIPH and GLIPH2, which group TCRs based on shared conserved sequences in the CDR3 region, enabling rapid clustering of thousands to millions of TCRs. This study identified TCR groups associated with infection control and performed antigen screening of MTB-C-reactive T cells to uncover potential subunit vaccine epitopes, offering new insights into tuberculosis vaccine development[66]. With the continuous advancement of sequencing technologies, particularly ONT nanopore sequencing, the potential for genomic research in vaccine development has increased significantly. The extended long reads provided by ONT sequencing revealed strain-specific structural variants in PE/PPE genes (such as PPE50), which serve as promising candidate loci for vaccine development. Through high-resolution genomic analysis, ONT has enabled the identification of complex structural variants, particularly in pathogens, such as MTBC, further driving progress in vaccine development[60].

-

HTS holds significant promise for advancing TB research; however, several challenges must be addressed before its full clinical potential can be realized. One primary obstacle is the high cost of HTS. Although the high upfront cost of HTS presents a significant barrier to its adoption for TB control, particularly in low-resource settings, this perspective overlooks the substantial downstream costs associated with conventional methods. Despite their low per-test prices, diagnostics such as culture-based pDST lead to extended hospitalizations, ineffective treatments, and continued transmission owing to prolonged turnaround times, creating an economic burden that can dwarf initial savings[67]. HTS is cost-effective as it mitigates these long-term expenses through a rapid, comprehensive diagnosis that enables targeted therapy and improved outcomes[68]. The economic viability of HTS has improved consistently with the advent of low-cost portable sequencing platforms. To leverage this, a concerted strategy that combines these technologies with international resource sharing and sustainable financial models such as subsidies and tiered pricing is needed to ensure equitable access.

In addition to economic considerations, ensuring HTS reproducibility is a key challenge for its clinical adoption. Discrepancies can arise at every stage of the workflow, including DNA extraction, sequencing platforms, and, most critically, non-standardized bioinformatics. The use of disparate software or filtering parameters can yield conflicting AMR profiles, thereby undermining diagnostic reliability. Therefore, effective clinical integration requires the translation of complex genomic data into clear and actionable reports for clinicians. This necessitates both validated automated bioinformatics pipelines for timely interpretation, and multidisciplinary teams comprising clinicians, scientists, and bioinformaticians to place genomic findings within the proper clinical context. These challenges underscore the urgent need for standardization. Global health organizations are spearheading such efforts. The WHO’s catalogue of MTBC mutations, for instance, serves as a universal reference for interpreting AMR, while organizations such as the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics are establishing external quality assessment schemes to ensure interlaboratory consistency[69].

The strategic advantage of HTS for TB control is context dependent. In high-resource settings, the primary benefit is the enabling of high-resolution public health surveillance through WGS for precise outbreak tracking and management of complex MDR-TB cases[70]. In high-burden, middle-income settings, the most significant advantage comes from rapid AMR detection using more targeted and cost-effective approaches, such as tNGS, which drastically shortens turnaround times and allows for timely initiation of appropriate therapy[68]. In low-resource settings where implementation remains challenging, the key potential advantage is the ability of portable sequencing technologies to leapfrog the need for an extensive culture-based laboratory infrastructure, thus decentralizing and expanding access to essential diagnostics[71].

Looking ahead, the future of HTS in TB research is promising owing to the anticipated advancements that are set to overcome current limitations and enhance its clinical utility. Emerging sequencing platforms are expected to be portable, cost-effective, and rapid, with innovations in microfluidics and portable devices that enable on-site genomic diagnostics in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into data analysis significantly improves the identification of resistance-associated mutations, thereby reducing diagnostic turnaround times and refining treatment regimens[72]. A pivotal future step is the direct integration of HTS data into clinical decision-support systems. Such systems can automatically process a patient’s AMR profile from their electronic health records, leverage real-time algorithms to recommend optimal personalized drug regimens and flag contraindications, and ensure alignment with public health guidelines. This seamless workflow would not only enhances clinical accuracy and standardizes care but also dramatically accelerates the initiation of effective treatment. In parallel, the development of standardized protocols and global data-sharing initiatives, supported by evolving regulatory frameworks and quality control measures, will ensure the reproducibility and clinical relevance of HTS findings[73].

-

This review demonstrates that HTS offers a transformative approach for TB diagnosis and control. HTS has significantly expanded the toolkit available for TB management by enabling rapid pathogen identification, precise AMR detection, comprehensive epidemiological analysis, and development of novel drugs and vaccines. These advancements translate into tangible benefits for the patients. Rapid and comprehensive AMR profiling is fundamental for personalized medicine and allows for the immediate selection of an optimal therapeutic regimen. This approach directly enhances patient outcomes by accelerating recovery, minimizing exposure to ineffective drugs, and curbing further transmission. Moreover, the diagnostic certainty afforded by HTS can strengthen treatment adherence, which is a critical factor in the success of prolonged courses of TB therapy. With further standardization and refinement of computational methodologies, HTS-based strategies have the potential to revolutionize clinical practice and public health initiatives worldwide. Continued global collaboration and targeted investment in HTS research, especially in resource-limited settings, are essential for translating these technological advances into effective TB control programs.

doi: 10.3967/bes2025.164

High-Throughput Sequencing for Tuberculosis Diagnosis and Antimicrobial Resistance Detection: Progress, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

-

Abstract: Tuberculosis (TB) continues to pose a significant threat to global public health, necessitating rapid and precise diagnostic methods and comprehensive detection of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to facilitate timely clinical management. Traditional diagnostic techniques suffer from extended turnaround times and limited ability to comprehensively profile AMR, often resulting in delayed therapeutic interventions. High-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies have revolutionized pathogen research by significantly improving diagnostic speed and accuracy. In the context of TB, diverse sequencing strategies and platforms are being employed to fulfill specific research goals, ranging from elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying AMR to characterizing the genomic diversity among clinical isolates. This review systematically examines current progress in the application of HTS for rapid pathogen identification, comprehensive AMR profiling, epidemiological studies, advances in novel drugs, and vaccine development. Furthermore, we address existing technological limitations and bioinformatics challenges and explore the future directions necessary for effectively integrating HTS-based methodologies into global TB control efforts.

-

Key words:

- Tuberculosis /

- Antimicrobial resistance /

- High-throughput sequencing

Writing-original draft: Lulu Zhang.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

注释:1) Authors’ Contributions: 2) Authors’ Contributions: 3) Authors’ Contributions: 4) Competing Interests: -

Figure 1. High throughput sequencing strategies for tuberculosis management are categorized into three complementary approaches based on analytical scope: targeted next generation sequencing, metagenomic next generation sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing. These strategies are applied in tuberculosis for pathogen diagnosis, antimicrobial resistance detection, epidemiology research, and the development of new drugs and vaccines.

Table 1. Comparative overview of HTS platforms for TB research

Manufacturer Representative Instruments Technology Read Length Accuracy Advantages Limitations Typical Applications Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq, NovaSeq Short-read sequencing 50–300 bp > 99.9% High throughput, cost-effective; widely used Short reads; limited complex region assembly Large-scale AMR profiling; epidemiological studies BGI MGISEQ-2000, DNBSEQ-T7 Short-read sequencing 50–400 bp > 99.9% High throughput; cost-effective Short reads; limited complex region assembly AMR surveillance; population-scale pathogen studies Ion Torrent Ion PGM, Ion Proton, Ion S5 Semiconductor sequencing 200–600 bp ~ 99.9% Rapid; flexible; suitable for clinical use Error-prone in homopolymer regions Rapid diagnostics; targeted AMR mutation detection PacBio Sequel IIe, Revio Single Molecule, Real-Time Sequencing 10–20 kb > 99.9% Long reads; high accuracy; good assembly Higher cost; lower throughput High-quality genome assemblies; complex genomic studies ONT MinION, GridION, PromethION Long-read nanopore sequencing 5–50 kb ~ 99.9% Portable; rapid results; real-time sequencing Higher error rate in homopolymer regions Field diagnostics, real-time AMR mutation detection Table 2. Comparative overview of HTS strategies in TB research

Strategy Scope Detection Coverage Advantages Limitations Typical Applications tNGS Selected resistance-associated genes or regions Known AMR targets Rapid; cost-effective; clinically actionable Limited targets; incomplete genomic data Rapid AMR diagnosis; clinical resistance profiling mNGS Unbiased sequencing of total DNA/RNA from clinical samples Broad pathogen detection (known/unknown, mixed infections) Hypothesis-free; comprehensive pathogen detection High cost; complex analysis; lower sensitivity for low-abundance pathogens Complex or unclear cases; pathogen discovery WGS Entire MTBC genome Comprehensive genomic information Complete genomic data; gold standard for AMR profiling and epidemiology Higher cost; complex data analysis; longer turnaround AMR mechanism research; outbreak tracking; public health surveillance Table 3. Comparative case studies on the application of HTS in TB management

Parameter Case 1: Critical MDR-TB Diagnosis Case 2: Public Health Outbreak Case 3: Paucibacillary TBM Diagnosis Clinical Scenario Critically ill, smear-negative pneumonia patient failing standard treatment;

high suspicion of MDR-TBA cluster of TB cases reported in a homeless shelter, requiring investigation of transmission links Patient with subacute neurological symptoms;

high suspicion of TBM but inconclusive initial testsSample Type Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid Sputum isolates from confirmed cases Cerebrospinal fluid HTS Strategies mNGS WGS tNGS Conventional TAT* 4–6 weeks 1–2 weeks Up to 6 weeks HTS TAT* 48 hours 3–5 days 72 hours Key HTS Findings Definitive detection of MTBC DNA;

Profiling of AMR mutationsSix of seven isolates formed a transmission cluster (≤ 5 SNPs), while the seventh was a genetically distinct outlier excluded from the outbreak Definitive detection of low-level MTBC DNA, confirming TBM where all other methods failed Clinical/Public Health Impact Immediate initiation of a life-saving, targeted second-line drug regimen Enabled a focused contact tracing investigation;

Prevented misallocation of resources;

Interrupted the chain of transmissionProvided a definitive diagnosis, allowing for confident initiation of anti-TB therapy;

Prevented severe neurological sequelae and avoided invasive brain biopsyPrimary HTS Advantage Speed & Comprehensiveness Resolution & Precision Sensitivity & Accuracy Note. *TAT, Turnaround Time. -

[1] Guinn KM, Rubin EJ. Tuberculosis: just the FAQs. mBio, 2017; 8, e01910−17. [2] World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2024. [3] Farhat M, Cox H, Ghanem M, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: a persistent global health concern. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2024; 22, 617−35. doi: 10.1038/s41579-024-01025-1 [4] Kontsevaya I, Cabibbe AM, Cirillo DM, et al. Update on the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2024; 30, 1115−22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2023.07.014 [5] Lin ZX, Sun LQ, Wang C, et al. Bottlenecks and recent advancements in detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis in patients with HIV. iLABMED, 2023; 1, 44−57. doi: 10.1002/ila2.11 [6] Demers AM, Venter A, Friedrich SO, et al. Direct susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for pyrazinamide by use of the Bactec MGIT 960 system. J Clin Microbiol, 2016; 54, 1276−81. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03162-15 [7] Bonnet M, Gabillard D, Domoua S, et al. High performance of systematic combined urine liboarabinomannan test and sputum xpert MTB/RIF for tuberculosis screening in severely immunosuppressed ambulatory adults with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis, 2023; 77, 112−9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad125 [8] Zhang C, Sun LY, Wang D, et al. Advances in antimicrobial resistance testing. Adv Clin Chem, 2022; 111, 1−68. [9] Meehan CJ, Goig GA, Kohl TA, et al. Whole genome sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: current standards and open issues. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2019; 17, 533−45. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0214-5 [10] Wang LL, Liu DK, Yung L, et al. Co-Infection with 4 species of mycobacteria identified by using next-generation sequencing. Emerg Infect Dis, 2021; 27, 2948−50. doi: 10.3201/eid2711.203458 [11] Goossens SN, Heupink TH, De Vos E, et al. Detection of minor variants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis whole genome sequencing data. Brief Bioinform, 2022; 23, bbab541. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab541 [12] World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection. 3rd ed. World Health Organization. 2023. [13] Lee JY. The principles and applications of high-throughput sequencing technologies. Dev Reprod, 2023; 27, 9−24. doi: 10.12717/DR.2023.27.1.9 [14] Reuter JA, Spacek DV, Snyder MP. High-throughput sequencing technologies. Mol Cell, 2015; 58, 586−97. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.004 [15] Cabibbe AM, Spitaleri A, Battaglia S, et al. Application of targeted next-generation sequencing assay on a portable sequencing platform for culture-free detection of drug-resistant tuberculosis from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol, 2020; 58, e00632−20. [16] Leung KSS, Tam KKG, Ng TTL, et al. Clinical utility of target amplicon sequencing test for rapid diagnosis of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis from respiratory specimens. Front Microbiol, 2022; 13, 974428. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.974428 [17] Mansoor H, Hirani N, Chavan V, et al. Clinical utility of target-based next-generation sequencing for drug-resistant TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2023; 27, 41−48. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.22.0138 [18] Iyer A, Ndlovu Z, Sharma J, et al. Operationalising targeted next-generation sequencing for routine diagnosis of drug-resistant TB. Public Health Action, 2023; 13, 43−49. doi: 10.5588/pha.22.0041 [19] Jouet A, Gaudin C, Badalato N, et al. Deep amplicon sequencing for culture-free prediction of susceptibility or resistance to 13 anti-tuberculous drugs. Eur Respir J, 2021; 57, 2002338. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02338-2020 [20] Gómez-González PJ, Campino S, Phelan JE, et al. Portable sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for clinical and epidemiological applications. Brief Bioinform, 2022; 23, bbac256. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac256 [21] Wang YH, Zhao Y, Bollas A, et al. Nanopore sequencing technology, bioinformatics and applications. Nat Biotechnol, 2021; 39, 1348−65. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01108-x [22] Zhang C, Zhang LL, Wang F, et al. Development and performance evaluation of a culture-independent nanopore amplicon-based sequencing method for accurate typing and antimicrobial resistance profiling in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Sci China Life Sci, 2024; 67, 421−23. doi: 10.1007/s11427-022-2382-0 [23] Zhang LL, Zhang C, Peng JP. Application of nanopore sequencing technology in the clinical diagnosis of infectious diseases. Biomed Environ Sci, 2022; 35, 381−92. [24] Guo YF, Li ZZ, Li LJ, et al. A dual-process of targeted and unbiased Nanopore sequencing enables accurate and rapid diagnosis of lower respiratory infections. eBioMedicine, 2023; 98, 104858. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104858 [25] World Health Organization. Use of targeted next-generation sequencing to detect drug-resistant tuberculosis: Rapid communication, July 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2023. [26] Guo YF, Li HN, Chen HB, et al. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing to identify pathogens and cancer in lung biopsy tissue. eBioMedicine, 2021; 73, 103639. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103639 [27] Guo XJ, Takiff HE, Wang J, et al. An office building outbreak: the changing epidemiology of tuberculosis in Shenzhen, China. Epidemiol Infect, 2020; 148, e59. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820000552 [28] Yu HY, Zhang Y, Chen XC, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analysis of a tuberculosis outbreak in a high school of southern China. Infect Genet Evol, 2020; 83, 104343. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104343 [29] Ransom EM, Potter RF, Dantas G, et al. Genomic prediction of antimicrobial resistance: ready or not, here it comes!. Clin Chem, 2020; 66, 1278−89. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa172 [30] Shi CL, Han P, Tang PJ, et al. Clinical metagenomic sequencing for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect, 2020; 81, 567−74. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.004 [31] Chen PX, Sun WW, He YY. Comparison of metagenomic next-generation sequencing technology, culture and GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Thorac Dis, 2020; 12, 4014−24. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-1232 [32] Yu GC, Shen YQ, Zhong FM, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of nanopore sequencing using respiratory specimens in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis, 2022; 122, 237−43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.06.001 [33] Zhou X, Wu HL, Ruan QL, et al. Clinical evaluation of diagnosis efficacy of active Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex infection via metagenomic next-generation sequencing of direct clinical samples. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2019; 9, 351. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00351 [34] Xu P, Yang K, Yang L, et al. Next-generation metagenome sequencing shows superior diagnostic performance in acid-fast staining sputum smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Front Microbiol, 2022; 13, 898195. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.898195 [35] Xiang ZB, Leng EL, Cao WF, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for diagnosing tuberculous meningitis. Front Immunol, 2023; 14, 1223675. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1223675 [36] Chen ST, Wang CL, Zou YJ, et al. Tuberculosis-targeted next-generation sequencing and machine learning: an ultrasensitive diagnostic strategy for paucibacillary pulmonary tuberculosis and tuberculous meningitis. Clin Chim Acta, 2024; 553, 117697. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2023.117697 [37] World Health Organization. The end TB strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [38] Wu SH, Xiao YX, Hsiao HC, et al. Development and assessment of a novel whole-gene-based targeted next-generation sequencing assay for detecting the susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to 14 drugs. Microbiol Spectr, 2022; 10, e02605−22. [39] Dippenaar A, Goossens SN, Grobbelaar M, et al. Nanopore sequencing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a critical review of the literature, new developments, and future opportunities. J Clin Microbiol, 2022; 60, e00646−21. [40] Tafess K, Ng TTL, Lao HY, et al. Targeted-sequencing workflows for comprehensive drug resistance profiling of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cultures using two commercial sequencing platforms: comparison of analytical and diagnostic performance, turnaround time, and cost. Clin Chem, 2020; 66, 809−20. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa092 [41] Chan WS, Au CH, Chung Y, et al. Rapid and economical drug resistance profiling with Nanopore MinION for clinical specimens with low bacillary burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Res Notes, 2020; 13, 444. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-05287-9 [42] Gliddon HD, Frampton D, Munsamy V, et al. A rapid drug resistance genotyping workflow for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, using targeted isothermal amplification and nanopore sequencing. Microbiol Spectr, 2021; 9, e00610−21. [43] Zhao KS, Tu CL, Chen W, et al. Rapid identification of drug-resistant tuberculosis genes using direct PCR amplification and oxford nanopore technology sequencing. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol, 2022; 2022, 7588033. [44] Votintseva AA, Bradley P, Pankhurst L, et al. Same-day diagnostic and surveillance data for tuberculosis via whole-genome sequencing of direct respiratory samples. J Clin Microbiol, 2017; 55, 1285−98. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02483-16 [45] Sun YK, Li XN, He JL, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and prediction of antibiotic resistance by nanopore adaptive sampling. iLABMED, 2024; 2, 266−76. doi: 10.1002/ila2.64 [46] Zhang LL, Yu X, Zhang C, et al. Development and comprehensive evaluation of culture-independent, long amplicon-based targeted next-generation sequencing methods for predicting antimicrobial resistance in tuberculosis. Anal Chem, 2025; 97, 281−89. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.4c04166 [47] Gliddon HD, Frampton D, Munsamy V, et al. A rapid drug resistance genotyping workflow for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, using targeted isothermal amplification and nanopore sequencing. Microbiol Spectr, 2021; 9, e00610-21. [48] Song J, Du WL, Liu ZC, et al. Application of amplicon-based targeted NGS technology for diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis using FFPE specimens. Microbiol Spectr, 2022; 10, e01358−21. [49] Zhang G, Zhang HQ, Zhang Y, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing technology showed great potential in identifying spinal tuberculosis and predicting the drug resistance. J Infect, 2023; 87, e110−2. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2023.10.018 [50] Coll F, Mcnerney R, Guerra-Assunção JA, et al. A robust SNP barcode for typing Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Nat Commun, 2014; 5, 4812. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5812 [51] Sharma MK, Stobart M, Akochy PM, et al. Evaluation of whole genome sequencing-based predictions of antimicrobial resistance to TB first line agents: a lesson from 5 years of data. Int J Mol Sci, 2024; 25, 6245. doi: 10.3390/ijms25116245 [52] Verboven L, Phelan J, Heupink TH, et al. TBProfiler for automated calling of the association with drug resistance of variants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One, 2022; 17, e0279644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279644 [53] Bradley P, Gordon NC, Walker TM, et al. Rapid antibiotic-resistance predictions from genome sequence data for Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Commun, 2015; 6, 10063. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10063 [54] Yang TT, Gan MY, Liu QY, et al. SAM-TB: a whole genome sequencing data analysis website for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance and transmission. Brief Bioinform, 2022; 23, bbac030. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac030 [55] Gröschel MI, Owens M, Freschi L, et al. GenTB: a user-friendly genome-based predictor for tuberculosis resistance powered by machine learning. Genome Med, 2021; 13, 138. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00953-4 [56] Jandrasits C, Kröger S, Haas W, et al. Computational pan-genome mapping and pairwise SNP-distance improve detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission clusters. PLoS Comput Biol, 2019; 15, e1007527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007527 [57] Song T, Dai HH, Wang S, et al. TransCluster: a cell-type identification method for single-cell RNA-Seq data using deep learning based on transformer. Front Genet, 2022; 13, 1038919. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.1038919 [58] Famulare M, Hu H. Extracting transmission networks from phylogeographic data for epidemic and endemic diseases: Ebola virus in Sierra Leone, 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza and polio in Nigeria. Int Health, 2015; 7, 298. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv031 [59] Didelot X, Fraser C, Gardy J, et al. Genomic infectious disease epidemiology in partially sampled and ongoing outbreaks. Mol Biol Evol, 2017; 34, 997−1007. [60] Thorpe J, Sawaengdee W, Ward D, et al. Multi-platform whole genome sequencing for tuberculosis clinical and surveillance applications. Sci Rep, 2024; 14, 5201. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55865-1 [61] Walker TM, Ip CL, Harrell RH, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2013; 13, 137−46. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70277-3 [62] Wilson MR, Sample HA, Zorn KC, et al. Clinical metagenomic sequencing for diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis. N Engl J Med, 2019; 380, 2327−40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803396 [63] Liu SD, Ye XC, Cheng F, et al. Clinical efficacy and computed tomography diagnostic value of bedaquiline‐containing regimens in the treatment of drug‐resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. iLABMED, 2024; 2, 149−56. doi: 10.1002/ila2.57 [64] The CRyPTIC Consortium. A data compendium associating the genomes of 12, 289 Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with quantitative resistance phenotypes to 13 antibiotics. PLoS Biol, 2022; 20, e3001721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001721 [65] The CRyPTIC Consortium and the 100, 000 Genomes Project. Prediction of susceptibility to first-line tuberculosis drugs by DNA sequencing. N Engl J Med, 2018; 379, 1403−15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800474 [66] Musvosvi M, Huang H, Wang CL, et al. T cell receptor repertoires associated with control and disease progression following Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Nat Med, 2023; 29, 258−69. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02110-9 [67] Assefa DG, Dememew ZG, Zeleke ED, et al. Financial burden of tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment for patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 2024; 24, 260. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-17713-9 [68] Shrestha S, Addae A, Miller C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS) for detection of tuberculosis drug resistance in India, South Africa and Georgia: a modeling analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 2025; 79, 103003. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.103003 [69] World Health Organization. Catalogue of mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and their association with drug resistance. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2023. [70] Pankhurst LJ, Del Ojo Elias C, Votintseva AA, et al. Rapid, comprehensive, and affordable mycobacterial diagnosis with whole-genome sequencing: a prospective study. Lancet Respir Med, 2016; 4, 49−58. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00466-X [71] Gómez-González PJ, Campino S, Phelan JE, et al. Portable sequencing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for clinical and epidemiological applications. Brief Bioinform, 2022; 23, bbac256. [72] Li LS, Zhuang L, Yang L, et al. Machine learning model based on SERPING1, C1QB, and C1QC: A novel diagnostic approach for latent tuberculosis infection. iLABMED, 2024; 2, 248−65. doi: 10.1002/ila2.65 [73] Tang YW, Yao JD. Bridging the divide: Harmonizing polarized clinical laboratory medicine practices. iLABMED, 2024; 2, 67−69. doi: 10.1002/ila2.46 -

下载:

下载:

Quick Links

Quick Links